Translate this page into:

Spared nerve injury model to study orofacial pain

Reprint requests: Dr Daniel Humberto Pozza, Department of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Al. Hernâni Monteiro 4200-319, Porto, Portugal e-mail: dhpozza@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

There are many difficulties in generating and testing orofacial pain in animal models. Thus, only a few and limited models that mimic the human condition are available. The aim of the present research was to develop a new model of trigeminal pain by using a spared nerve injury (SNI) surgical approach in the rat face (SNI-face).

Methods:

Under anaesthesia, a small incision was made in the infraorbital region of adult male Wistar rats. Three of the main infraorbital nerve branches were tightly ligated and a 2 mm segment distal to the ligation was resected. Control rats were sham-operated by exposing the nerves. Chemical hyperalgesia was evaluated 15 days after the surgery by analyzing the time spent in face grooming activity and the number of head withdrawals in response to the orofacial formalin test.

Results:

SNI-face rats presented a significant increase of the formalin-induced pain-related behaviours evaluated both in the acute and tonic phases (expected biphasic pattern), in comparison to sham controls.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The SNI-face model in the rat appears to be a valid approach to evaluate experimental trigeminal pain. Ongoing studies will test the usefulness of this model to evaluate therapeutic strategies for the treatment of orofacial pain.

Keywords

Experimental animal models

formalin test

neuropathy

orofacial pain

pain measurement

trigeminal nerve

Animal studies performed in orofacial pain have been relatively few, mainly because of the difficulties in testing freely moving animals1. A rat model where neuropathy was produced by chronic constriction injury of the infraorbital branch of the trigeminal nerve (CCI-TN) has been developed for studying orofacial neuropathic pain2. This model induces significant inflammatory response and the optimum degree of nerve constriction is difficult to achieve3. In addition, the surgical approach for CCI-TN is more complex than for other peripheral nerves such as the sciatic4. As an alternative, some investigators proposed the transection of the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN)56 that causes an afferent hyperexcitability of the injured IAN leading to orofacial allodynia6.

On the other hand, the spared nerve injury (SNI) approach for modelling clinical neuropathic pain has been widely used since it is technically easy to perform and subject to minimal variability. The sensitive maxillary nerve is the major branch of the trigeminal nerve (infraorbital nerve or ION) and does not contain any autonomic or motor fibers78.

Different tests are used to access behaviour in animal pain models. The formalin test, that is one of the most frequently used in the orofacial region, evaluates the behavioural responses to a prolonged noxious chemical stimulus and can be used for the assessment of pain and analgesia in rats1. Formalin solution injected into the rat's ION territory (orofacial formalin test) evokes two distinct periods of intensive grooming activity and it has been validated by analgesic treatments910. Face grooming and brisk head withdrawals are both considered pain-like behaviours and represent nocifensive responses to the formalin test211.

In this study we adapted the spared nerve injury (SNI) model of the sciatic nerve12 to the infraorbital nerve to develop a SNI-face model of trigeminal pain in rats, and evaluated hyperalgesia by using the orofacial formalin test.

Material & Methods

Adult male Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, France) weighing between 270 and 300 g were housed in pairs (belonging to the same group) with water and food ad libitum. The experiments were performed in the department of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Medicine of Porto University, Porto, Portugal. The animal room was maintained at a constant temperature of 22°C with controlled light (12 h light/dark cycles). All experiments followed the ethical guidelines for the study of experimental pain in conscious animals13 and the study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the institution. Additionally, all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. Eighteen animals were used in the present research: eight for the surgical technique/behaviour tests improvement, six in the experimental group (SNI-face; based on the SNI model of the sciatic nerve), and four in the control group.

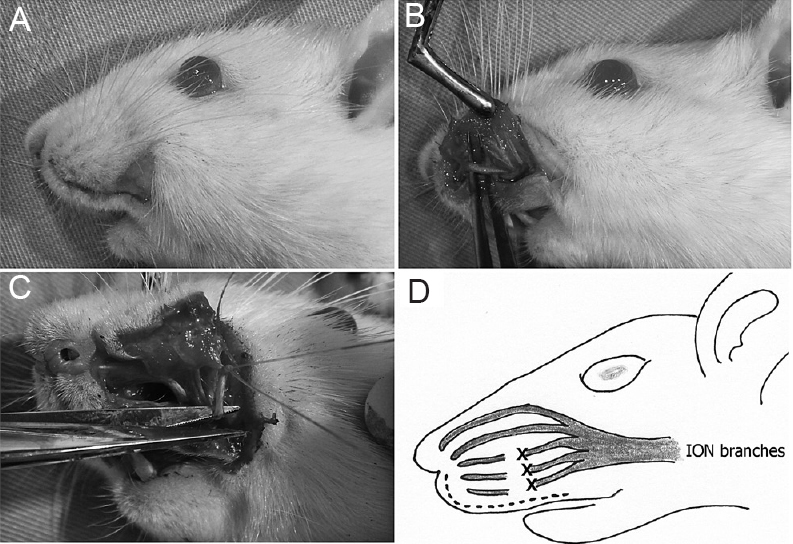

SNI-face procedure: The animals were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (Ketalar, 60 mg/kg) and medetomidine hydrochloride (Domitor, 0.25 mg/kg). After trichotomy, a small “L” shape incision, approximately 10 mm long, was performed in the skin of the infraorbital region, avoiding the vibrissae pad and eye region, and following the anatomy of the upper lip (Fig. 1A). Soft tissues were gently dissected exposing the main ION branches (Fig. 1B). The three nerve branches more distal to midline were carefully separated from the soft tissue, tightly ligated and 2 mm segment of the nerve distal to the ligation was resected from each branch (Figs 1C, 1D). Caution was taken not to stretch or touch the intact spared branch. Control rats were sham-operated by exposing the main ION branches using the same protocol, but ligation and transection were not performed. Skin wounds were closed by 5-0 silk isolated sutures. During surgery, the eyes of the rats were kept humid with saline. The animals were allowed to recover from the surgery for 15 days before the formalin test was performed. Previous pilot studies at seven, ten and 12 days demonstrated absence of marked hyperalgesia in the experimental group.

- Surgical technique. (A) Incision following the anatomy of the upper lip. (B) Exposure of the main infra orbital nerve (ION) branches. (C) Nerve ligation and subsequent removal of the distal segment. (D) Scheme of the ligation and 2 mm segment removal in the three more distal ION nerve branches: “X”. Dotted line: incision.

Orofacial formalin test: Nociceptive behaviour was evaluated by the formalin test (acute and tonic pain) in the face. Fifteen days after the SNI-face or sham surgery, rats from both groups were gently immobilized by wrapping them in a towel and 50 μl of 3 per cent neutral formalin was subcutaneously injected into the vibrissae pad, with a 27-gauge needle910.

The rats were placed in the test chamber immediately after and their behaviour was recorded with a video camera connected to a computer during the following 50 min. Immediately after the video recording, rats were sacrificed by intracardiac injection of sodium pentobarbital (75 mg/kg). The behaviour scoring was performed by using the Etholog 2.25 free software14. The video-analysis focused on the following behaviours that were scored during the 10 successive periods of five min each (i) the number of brisk head withdrawals; (ii) time spent in performing face grooming activities (movement patterns in which paws contact facial areas, including wash strokes and flinching or shielding the face). The area under the curve (AUC) was also calculated for each plot.

Statistical analysis: The effect of group (between-subjects effect) and the interactions between group and time (within-subjects effect) were tested in the repeated measures in general linear models. Whenever group-time interactions were significant, Mann-Whitney U test was used to test the differences between groups for each of the time points analyzed. Mann-Whitney U test was also used to assess differences in the AUC for each formalin-evoked nociceptive behaviour analyzed between sham and SNI-face groups. The statistical analysis was performed using the software programs SPSS 18.0® (IBM, Corporation, USA) and Graphpad® (GraphPad Software, Inc. CA, USA).

Results

The test animals with spared nerve injury of the face presented an increase in grooming activity and head withdrawal behaviours following orofacial formalin injection when compared with sham-operated controls, indicating decreased thresholds to chemical noxious stimulation.

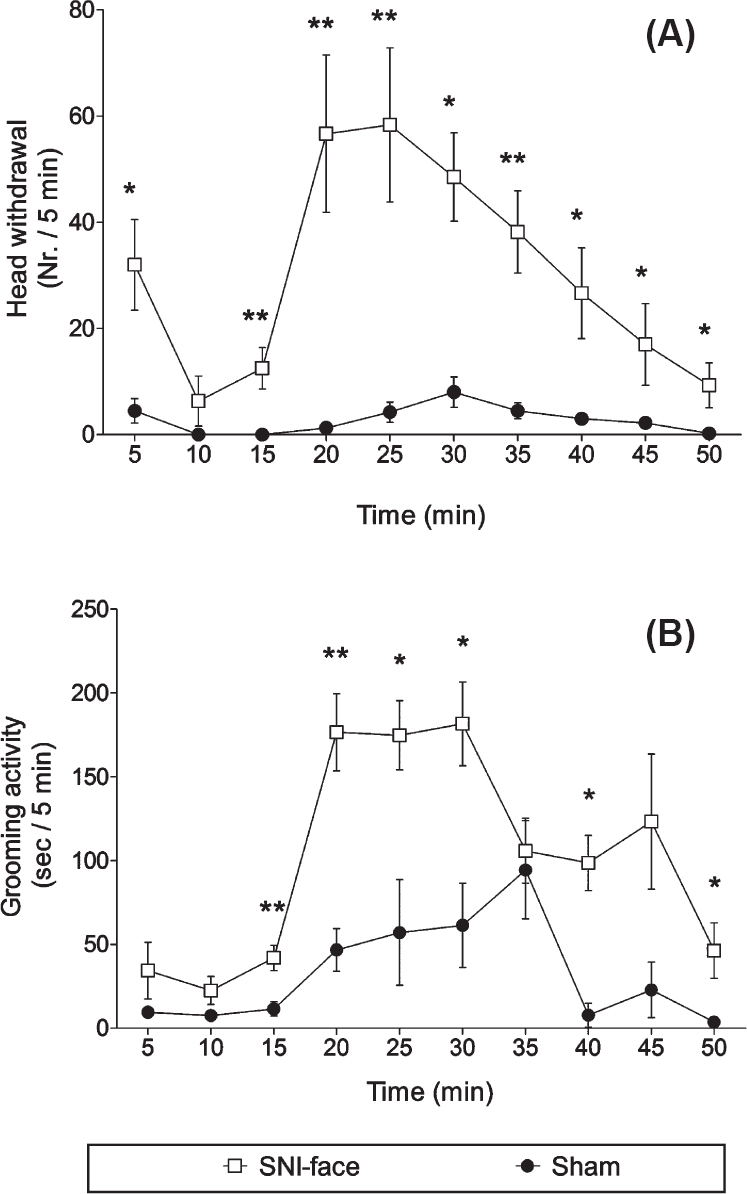

Pain-related behaviours upon formalin injection into the vibrissae pad were observed in the two phases of the test including head withdrawal and grooming activity (Fig. 2). Statistical significances between SNI-face and sham groups in grooming activity (P<0.001) and head withdrawal reflex (P<0.01) were found by using the repeated measures in general linear models analysis. Thus, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed in each time point for both behaviours. Statistical significances (P<0.05 or P<0.01 depending on time points) were observed at all time points evaluated except at 10 min for head withdrawal (Fig. 2A), and at 15, 20, 25, 30, 40 and 50 min after formalin injection into the vibrissae pad for the grooming behaviour (Fig. 2B).

- Pain behaviours in the orofacial formalin test. Graphics illustrate the time-course of the formalin test performed in either spared nerve injury (SNI)-face (n=6) or sham (n=4) rats injected into the vibrissae pad with 3 per cent formalin. (A) Number (Nr) of head withdrawal reflexes; (B) Time in seconds (sec) spent in grooming activity. Data were collected in 10 successive periods of 5 min after injection of formalin (time 0) and are presented as mean ± SEM. *P<0.05, **P≤0.01 compared to sham.

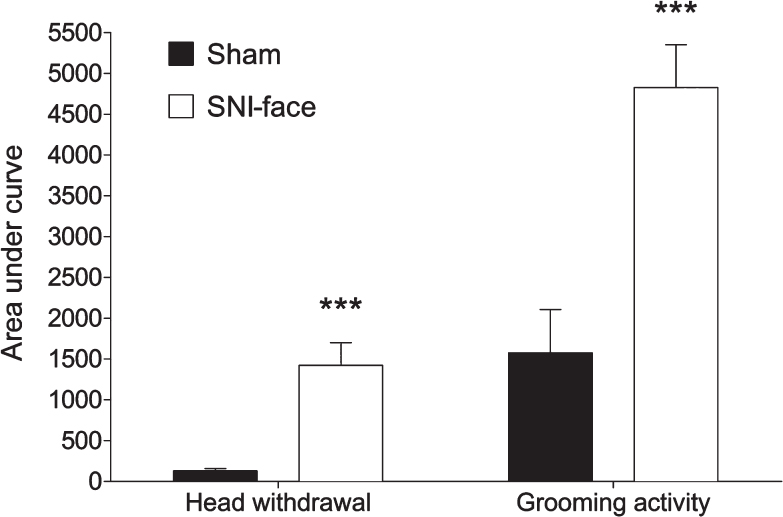

AUC values indicated that SNI-face rats presented significantly enhanced nociceptive behaviour following formalin injection when compared to sham-operated controls (Fig. 3).

- Bars illustrate the area under the curve (AUC) in both SNI-face (white bars, n=6) and sham (black bars, n=4) animals for the head withdrawal reflex and grooming activity performed in response to formalin injection into the vibrissae pad. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. *** P<0.001 compared to sham.

Discussion

The present study shows that the spared nerve injury model of the sciatic nerve12 can be easily adapted to create a model of orofacial pain in rats, with development of chemical hyperalgesia. It is well known that the animal models of CCI of the sciatic or trigeminal nerves can mimic neuropathic pain found in humans2715. However, they present some limitations because tightly placed chromic gut sutures produce anaesthesia while loose sutures produce no abnormalities or pain behaviours1316. This difficulty in finding the exact degree of constriction can contribute to the relatively low number of animals that develop neuropathic pain (30-40%)1516.

Another difficulty of performing the CCI in the trigeminal nerve is the specific suture required. The chemicals present in chromic gut, when in contact with the nerve, are necessary to generate thermal hyperalgesia, in contrast to plain gut or silk sutures. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that chromic gut sutures tied loosely around the sciatic nerve generate a thick encapsulation of the ligatures. So constriction injury may not be the primary event leading to the behavioural signs of neuropathic pain, but the inflammation following handing111718. Thus, there is some controversy about the validity of CCI as a neuropathic pain model since a strong inflammatory response has also been observed31617. The SNI model allows studying neuropathic pain in the sciatic and trigeminal nerves without the influence of the chromic gut in the suture material used in the CCI model.

Performing the CCI using chromic sutures in combination with a partial axotomy has also been proposed19, but it still requires chromic ligatures. In addition, as demonstrated in the present study, the axotomy per se is enough to generate chemical hyperalgesia. Alternatively, other investigators transected the mandibular nerve (inferior alveolar nerve model) causing orofacial allodynia67. However, the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve contains a motor component and this can cause a less objective interpretation of the behavioural tests4.

Although different surgical approaches may be executed, some authors proposed a different intra-oral approach to avoid damaging the skin in an area that might be used later for the sensory tests20. Though this approach was not used in the present SNI-face model, the skin of the rats was already healed 15 days after the surgery, being difficult to differentiate from the healthy contralateral vibrissae pad. Moreover, the animals did not present any difficulty in feeding and the sensory testing region was not affected by the surgical procedure. Alternatively, a midline incision over the snout which allows a good visualization of the ION can be performed19, or an incision in the skin of the snout, under the right eye, about 3 mm caudal to the mystacial pads21. All these approaches require special care to avoid damage of the facial nerves and other structures, such as the eye, and these do not allow the access to the multiple nerve fascicles as obtained in the SNI-face model.

To evaluate chemical hyperalgesia in the SNI-face model, we analyzed the grooming activity as well as head withdrawal in response to formalin injection. Face grooming, that is neither preceded nor followed by body grooming, is the most obvious quantitative behaviour measured during facial noxious stimulation2, and can be used as a sign of localized orofacial pain12223.

In the SNI-face rats, the observations were similar to that found by others1124 who observed increased face grooming in the first three minutes, followed by a decrease to very low levels between 6 and 12 min, when the second phase of the formalin test started. However, other authors observed first formalin phase lasting six minutes and a delayed and prolonged tonic phase occurring between 12 and 42 min, which were separated by a period of relative inactivity22. In SNI-face rats, the grooming activity in the first formalin phase was not significantly increased, and more obvious pain-related behaviours were observed in the second phase.

Besides grooming activity2, we also evaluated the head withdrawal reflexes. Mechanical stimulation in the rat face requires a long habituation period to acclimate the rats to the testing environment. The complexity of whisker movements and sensory information transmitted through the facial hair can complicate testing. Holding the animals generates stress, restricts free movements and limits the scope of response1. During our preliminary studies, we realized that some animals became very aggressive against the filaments, while others presented no reaction to the mechanical stimulation. Therefore, as an alternative we evaluated the head withdrawal reflexes evoked during the orofacial formalin test, allowing free movements and a similar reaction to the chemical stimulus to all the animals. In the SNI-face animals, head withdrawal was the most consistent behaviour, following the biphasic formalin curve, being comparable to the paw jerks already described in the hind paw formalin test25.

The formalin test was performed 15 days after the surgery based on other CCI-TN studies where mechanical allodynia started on days 7 to 15, and rats exhibited abnormal pain sensitivity that was stable even at post-operative day 30. Additionally, decreased responsiveness to stimulation of the territory of the ligated ION is expected over 12 postoperative days226. In the early period after ION ligation most rats do not respond to stimulation, while after 15 days, they perform more face grooming episodes and become hyperresponsive to all stimuli applied to the ION territory2. Thus, we decided to perform the test 15 days after the surgery, which also allowed proper surgical wound healing.

In summary, the SNI-face model is a simple procedure that looks suitable to study trigeminal pain, with minor limitations. The chemical hyperalgesia observed in SNI-face rats was related to the model itself since SNI-face exhibited exacerbated pain-related activities after formalin-induced noxious stimulation. The preliminary nature of this work requires further behavioural and pharmacological studies to test the usefulness of this model to evaluate therapeutic strategies for orofacial pain.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Behavioral testing in rodent models of orofacial neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Brain behav. 2012;2:678-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Behavioral evidence of trigeminal neuropathic pain following chronic constriction injury to the rat's infraorbital nerve. J neurosci. 1994;14:2708-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interleukin-6 and nerve growth factor levels in peripheral nerve and brainstem after trigeminal nerve injury in the rat. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:633-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic constriction injury of the infraorbital nerve in the rat using modified syringe needle. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;172:43-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction of Fos protein-like immunoreactivity in the trigeminal spinal nucleus caudalis and upper cervical cord following noxious and non-noxious mechanical stimulation of the whisker pad of the rat with an inferior alveolar nerve transection. Pain. 2002;95:225-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral mechanisms for the initiation of pain following trigeminal nerve injury. J orofac pain. 2004;18:287-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms involved in modulation of trigeminal primary afferent activity in rats with peripheral mononeuropathy. Eur j neurosci. 2006;24:1976-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direct reticular projections of trigeminal sensory fibers immunoreactive to CGRP: potential monosynaptic somatoautonomic projections. Front neurosci. 2014;8:136.

- [Google Scholar]

- The orofacial formalin test in rats: effects of different formalin concentrations. Pain. 1995;62:295-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for a peripheral origin of the tonic nociceptive response to subcutaneous formalin. Pain. 1995;61:11-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inflammatory hypersensitivity in a rat model of trigeminal neuropathic pain. Arch oral biol. 2003;48:161-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain. 2000;87:149-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain. 1983;16:109-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- EthoLog 2.2: a tool for the transcription and timing of behavior observation sessions. ehav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2000;32:446-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- A time course analysis of the changes in spontaneous and evoked behaviour in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 1992;50:101-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible chemical contribution from chromic gut sutures produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1993;54:57-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of four different suture materials in soft tissues of rats. Oral Dis. 2003;9:284-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sodium channel Nav1.6 accumulates at the site of infraorbital nerve injury. BMC Neurosci. 2007;8:56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of heat-hyperalgesia in an experimental trigeminal neuropathy in rats. Exp Brain Res. 1997;116:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Orofacial cold hyperalgesia due to infraorbital nerve constriction injury in rats: reversal by endothelin receptor antagonists but not non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Pain. 2006;123:64-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- The peripheral antinociceptive effect of morphine in a rat model of facial pain. Neuroscience. 1996;72:519-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Behavioral assessment of facial pain in rats: face grooming patterns after painful and non-painful sensory disturbances in the territory of the rat's infraorbital nerve. Pain. 1998;76:173-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral substance P and neurokinin-1 receptors have a role in inflammatory and neuropathic orofacial pain models. Neuropeptides. 2013;47:199-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental model of trigeminal pain in the rat by constriction of one infraorbital nerve: changes in neuronal activities in the somatosensory cortices corresponding to the infraorbital nerve. Exp brain res. 1999;126:383-98.

- [Google Scholar]