Translate this page into:

Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India & their perceptions on the way forward - A qualitative study

For correspondence: Dr Beena E. Thomas, (Rtd.) Head of the Department of Social and Behavioural Research, ICMR-National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, No. 1, Mayor Sathyamurthi Road, Chetpet, Chennai 600 031, Tamil Nadu, India e-mail: beenaelli09@gmail.com

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The healthcare system across the world has been overburdened due to the COVID-19 pandemic impacting healthcare workers (HCWs) in different ways. The present study provides an insight into the psychosocial challenges faced by the HCWs related to their work, family and personal well-being and the associated stigmas. Additionally, the coping mechanisms adopted by them and their perceptions on the interventions to address these challenges were also explored.

Methods:

A qualitative study was conducted between September and December 2020 through in-depth telephonic interviews using an interview guide among 111 HCWs who were involved in COVID-19 management across 10 States in India.

Results:

HCWs report major changes in work-life environment that included excessive workload with erratic timings accentuated with the extended duration of inconvenient personal protection equipment usage, periods of quarantine and long durations of separation from family. Family-related issues were manifold; the main challenge being separated from family, the challenge of caregiving, especially for females with infants and children, and fears around infecting family. Stigma from the community and peers fuelled by the fear of infection was manifested through avoidance and rejection. Coping strategies included peer, family support and the positive experiences manifested as appreciation and recognition for their contribution during the pandemic.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study demonstrates the psychological burden of HCWs engaged with COVID-19 care services. The study findings point to need-based psychosocial interventions at the organizational, societal and individual levels. This includes a conducive working environment involving periodic evaluation of the HCW problems, rotation of workforce by engaging more staff, debunking of false information, community and HCW involvement in COVID sensitization to allay fears and prevent stigma associated with COVID-19 infection/transmission and finally need-based psychological support for them and their families.

Keywords

Coping

COVID-19

healthcare workers

India

psychosocial

qualitative

stigma

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has affected people in more than one way. It is accompanied by various morbidity and mortality trajectories with long lasting effects1 impacting public health, with psychosocial consequences across the globe2. This upsurge in COVID-19 cases has heavily burdened and in many cases overwhelmed and impaired the healthcare systems34.

Healthcare workers (HCWs) across the globe have experienced an increase in their work volume and intensity, additional responsibilities, and have had to adapt to new protocols and adjust to the ‘new normality’56. This pandemic has been clouded with uncertainties accompanied by high transmission rates which have challenged HCWs to a large extent. On the one hand, they need to respond to their call to serve humanity, and on the other hand, they are gripped with the fear of infection through the provision of care. This is a paradox that has resulted in psychological distress including depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among HCWs78. The WHO has recognized and affirmed the need for action to address the impact on the physical and mental health of HCWs9.

Furthermore, this pandemic has brought out different expressions of stigma that HCWs face with experiences of verbal and physical abuse reported to a large extent in social and print media platforms. Manifestations of stigma have been reported in India with doctors, and nurses being forced to vacate from their premises and reports of physical violence on HCWs in many parts of the nation1011. Similar experiences of stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic have been reported from all over the world1213.

Recent studies have also documented stress, anxiety, depression and sleep-related issues among HCWs14151617. However, there is a dearth of qualitative data from India on the psychosocial impact of COVID-19 on HCWs. It is against this background that this study aimed to provide an insight into the psychosocial challenges faced by HCWs related to their work-life, family relationships, personal well-being and the experiences of stigma at various levels. Another area that this study explored are the coping strategies adopted by HCWs to face these challenges and capture their suggestions on how these psychosocial challenges should be addressed. The overall purpose of this study was to help promote need-based intervention strategies for HCWs to improve their mental well-being, which would in turn help towards a better health system for patient-centred quality care.

Material & Methods

This study was part of a cross-sectional multicentre study carried out in 10 States across India to explore the psychosocial experiences of HCWs involved in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was conducted between September and December 2020 and adopted a mixed-methods design that included both quantitative as well as qualitative investigations done in parallel. Ethical clearance was obtained from the National Central Ethics Committee of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) (CECHR 012/2020). Approval was sought from the Institutional Ethics Committees of the 10 co-ordinating centres at each of the study sites.

The sample size calculation for the larger study used a cross-sectional design assuming a 50 per cent prevalence of psychological distress, 15 per cent non-compliance with an alpha error of five per cent and relative precision of 10 per cent. Quantitative data were collected from 967 participants from the 10 States. Approximately, one tenth of this sample was covered for qualitative investigation to help gain a deeper and clearer understanding of the psychosocial impact of this pandemic, their coping strategies, as well as their suggestions on how to address these experiences. The total number covered was 111 participants across the sites with 9-11 respondents per site which was sufficient to reach saturation, crucial for qualitative data analysis.

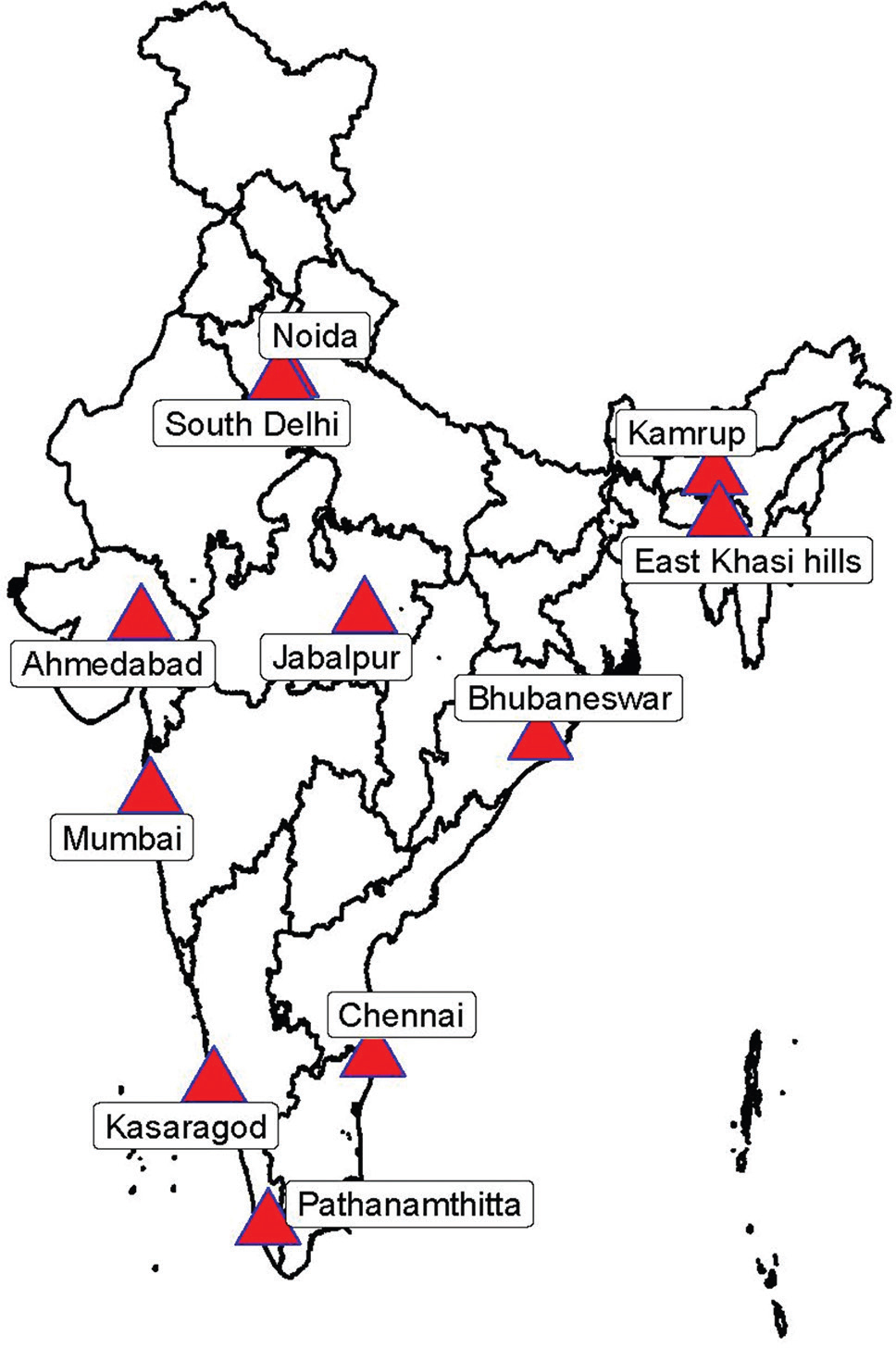

Study sites: The study sites across the 10 Indian States that were covered for this study included Bhubaneswar (Odisha), Mumbai (Maharashtra), Ahmedabad (Gujarat), Noida (Uttar Pradesh), South Delhi, Pathanamthitta (Kerala), Kasaragod (Kerala), Chennai (Tamil Nadu), Jabalpur (Madhya Pradesh), Kamrup (Assam) and East Khasi Hills (Meghalaya) (Fig. 1).

- Map showing study sites (Note: Map not to scale). The map was developed using ArcGIS version 10.7.1 (Licenced to ICMR-National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai, India) using the geo-referenced data.

Recruitment of participants and data collection: Considering the diversity of the population, purposive sampling was used to recruit participants. The initial step was to list public and private hospitals in each site that were involved in the provision of COVID-19 healthcare services. The principal investigators of different sites contacted the health authorities, explained the purpose of the study, and sought their consent and cooperation to carry out the study. The health facilities, willing to participate, were listed as potential sites for the conduct of the study.

Eligible study participants were HCWs involved in COVID-19 care services ranging from triaging, screening, treatment, isolation, referral services and community outreach services. These included doctors, nurses, pharmacists, ambulance workers, community workers, housekeeping staff, security guards, stretcher-bearers, sanitation workers, laboratory staff and hospital attendants. The screening for eligibility of the study participants and interviews were carried out by 2-3 field researchers at each site who had a Master's Degree in social sciences/social work/psychology with prior experience in conducting qualitative interviews. The interviews were conducted telephonically as compared to the preferred face-to-face interviews for the collection of sensitive qualitative data, such as what was required for the present study. This was done to ensure the safety and precautionary measures advised in view of the pandemic, the population covered and the length of the interviews. The investigators were provided intensive training on conducting the telephonic interviews which included building trust, consent procedures, the interview structure and the likely challenges they would face in the process and other skills required in conducting telephonic interviews.

Once the final list of eligible participants was prepared after the screening process, the research investigators individually contacted the eligible participants over telephone. The purpose of the study was explained with the help of a participant information sheet, and their willingness to be part of this study through audio consent was obtained. In addition, permission was obtained from the participants for the interview to be audio-recorded. The investigators fixed an appointment with the HCWs based on their convenience to ensure that the interview did not interfere with their work and time with family. In some instances, these appointments needed to be rearranged if the HCWs could not keep up the appointment due to work or family commitments. Each of the interviews lasted for 30-40 minutes. Venues for interviews included various settings such as the workplace, their homes and the care centres where they were being quarantined after their COVID-19 care duty.

The telephonic interviews were conducted using an interview guide for uniformity. The guide consisted of questions related to five core domains – impact on work–life, impact on family life, impact on the sense of well-being, coping during COVID-19 and suggestions on addressing the psychosocial challenges and mitigating the stigma associated with managing patients with COVID-19 infection. Each domain had a set of questions, followed by context-relevant probes to clarify and unpack their responses, experiences, and perceptions in relation to the phenomena under study (Box).

| I. Impact on work life |

| Question: We would like to know how your work life has changed due to COVID 19 (please elaborate) |

| Probe issues such as burden of work, stigma, work relationships and family |

| II. Impact on family life |

| Question: We would like to know, how your family life has changed due to COVID-19 (Please elaborate) |

| Probe issues such as time spent with family, stigma, and relationships within the family |

| III. Impact on sense of well-being |

| Question: We would like to know, how this experience of working with COVID has influenced you personally |

| Probe issues such as sleep, eating habits, job satisfaction, overall motivation, stigma and happiness |

| IV. Coping during COVID-19 |

| Question: How have you managed to cope with all the challenges you had to face due to COVID-19 |

| Probe issues such as sharing experiences with others (family members, friends, and colleagues), exercise and music |

| V. Suggestions on how to mitigate the stigma due to COVID-19 |

| Question: What interventions do they think are needed to mitigate the stigma that many healthcare providers are facing due to COVID-19 |

| Probe issues such as information that is needed, interventions within the health system, within families and communities |

The interviews were conducted in the local languages (Tamil/Hindi/Marathi/Malayalam/Odia/Gujarati/Assamese/Khasi) audio-recorded, transcribed and translated to English. To ensure the safety and privacy of the participants, personal identifiers provided during the interview was encrypted.

Data analysis: Transcribed interviews were coded using a thematic approach and analyzed using NVivo software (QSR International, UK). Using the qualitative interview guide which already had distinct domains requiring exploration as the foundation, the possible codes (themes) were identified by the study team using an inductive approach. The transcripts were then independently coded by two researchers, and additional relevant themes and sub-themes were identified using descriptive content analysis from the data without applying a preconceived theoretical framework. In parallel, the researchers tracked new codes added to the coding scheme to describe the unexpected themes that emerged. The two researchers frequently met between themselves and with the site field investigators to reconcile inconsistencies in the application of codes and to ensure that emergent codes were added to the coding scheme. Because all coding differences were reconciled by consensus, the inter-rater reliability between the coders was not assessed. The data were analyzed and emergent themes were organized within these constructs with illustrative quotations selected for each theme. In reporting the study findings, the principles of qualitative research were followed by avoiding the quantification of codes (or themes) from our data18. The study findings reported are as common themes (i.e. those that emerged most frequently) and salient themes (i.e. themes reported by a minority that are still important).

Results

There was a fairly similar representation of gender in this study with 54 per cent females and 46 per cent males (Table I); the respondents were primarily in the age group between 20 and 40 yr (84%) (Table I).

| Characteristics | Values, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 51 (46) |

| Female | 60 (54) |

| Age group (yr) | |

| 20-30 | 41 (37) |

| 31-40 | 52 (47) |

| 41-50 | 18 (16) |

| Type of healthcare worker | |

| Doctor | 25 (23) |

| Nurse | 36 (32) |

| Ambulance worker | 14 (13) |

| Community worker | 9 (8) |

| Housekeeping/security guard | 10 (9) |

| Laboratory staff | 17 (15) |

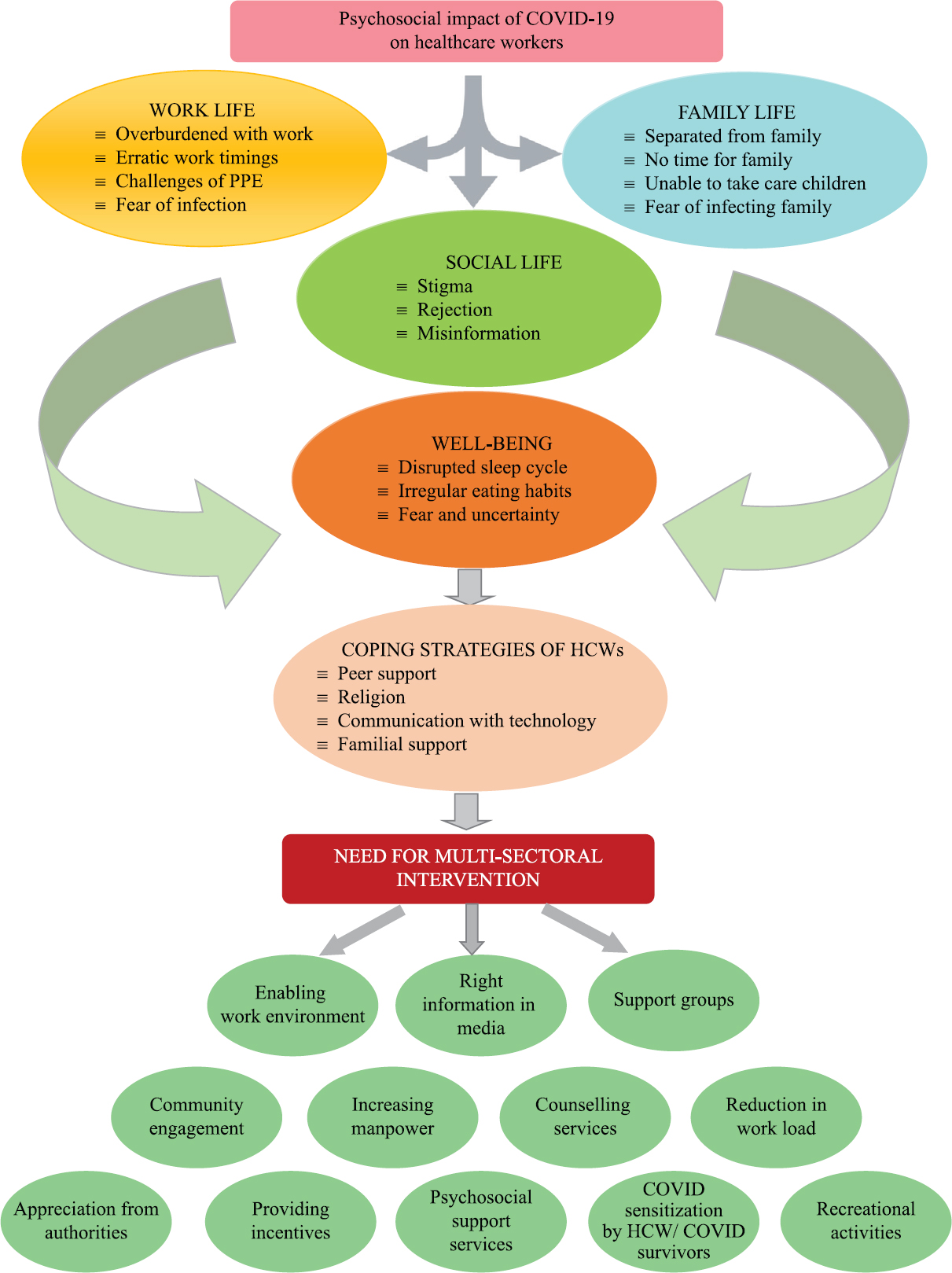

Broad domains were used that were explored through our interview guide to present the findings with themes and sub-themes that emerged under them as shown in Table II. This included (i) work-related issues, (ii) family-related issues, (iii) societal-related issues, (iv) individual-related issues, (v) coping mechanisms and (vi) suggestions on the way forward (Table II and Fig. 2).

| Themes | Key finding(s) |

|---|---|

| Work related | Changes in the work routine |

| Increased work load | |

| Erratic work timings | |

| Challenges with PPE | |

| Fear of infection | |

| Family related | Separation from families |

| No time with family | |

| Gender differences in experiences with family | |

| Fear of infecting families | |

| Non-disclosure of COVID duties to family | |

| Individual level | Sleep deprivation |

| Disruption in eating habits | |

| Society level | Stigma and rejection |

| Coping during COVID-19 | Family and friends support |

| Peer support | |

| Listening to music/yoga | |

| Religion | |

| Positive experiences that helped sense of well being |

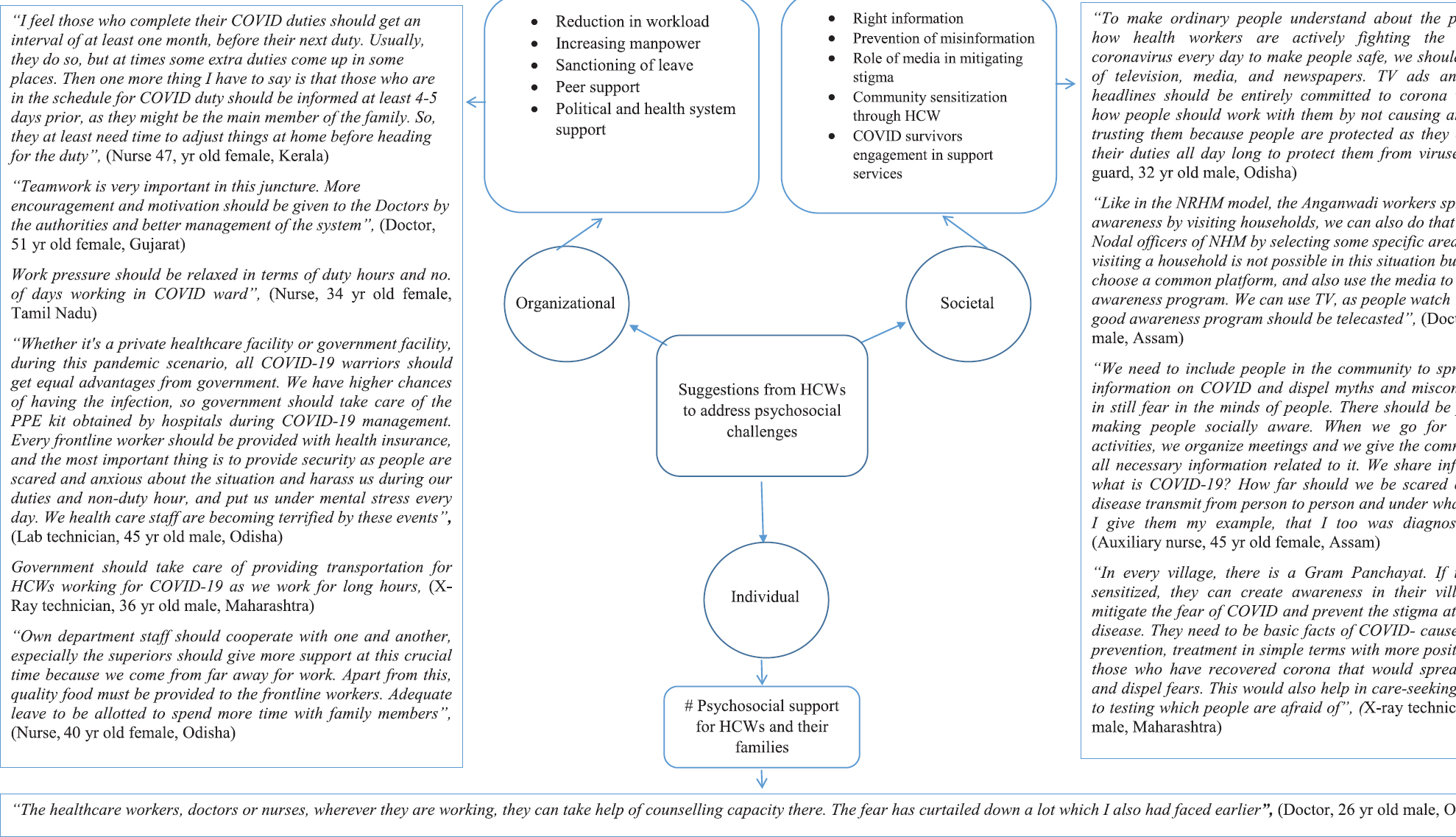

- Suggestions of healthcare workers on how to address psychosocial challenges.

Work-related issues: Various aspects emerged with regard to work-life environment which impacted HCWs. These are listed under the main theme of work-related issues and elaborated on the various sub-themes namely, changes in a work routine, increased workload, erratic work timings, challenges with personal protection equipment (PPE) and fear of infection.

Changes in the work routine: All study participants believed that there were major changes in their work-life routine with the onset of the pandemic. Most of them reported a big change in roles and responsibilities, which were beyond their usual routine. While some found it stressful, there were a few who expressed confusion they faced with their duties, especially in the wake of emergencies. This was accompanied by the uncertainty of what needed to be done which was different from the protocol they were used to, while dealing with patients.

“With COVID, there is additional stress related to our work. Earlier, once we receive an emergency call, we know what we are dealing with. But now, if we go to the casualty to attend to the patient, we have to be in our PPE kit. If the patient is positive for COVID-19 and the patient is sick and needs emergency care, the emergency procedures like intubation is a challenge. We not only have to do COVID duty but we are seeing the other patients also”, (Doctor, 33 yr old female)

Increased workload: Apart from the change of roles and responsibilities, the increased work that came with it was a stress factor most often expressed by the HCWs. “There is lots of pressure and we are overloaded with work. We get too tired and we get angry too because we have to deal with the public especially those who don’t understand the situation”, (Ambulance worker, 32 yr old female).

Erratic work timings: Most respondents expressed that the erratic work timing was a challenge across all layers that included doctors, nurses, ambulance drivers and supporting staff. Many of them also reported that this along with the workload did not allow them to take their eligible leave to go home to be with their families.

Challenges with personal protective equipment (PPE): The new concept of protection with a PPE in dealing with patients with COVID-19 had a number of its own challenges among HCWs impacting their work culture in many ways.

-

“Wearing the PPE kit is very difficult because once worn, I cannot remove it for 4-5 h, and at that time, I cannot have anything to eat or drink. I have to refrain from even going to the restroom. It gets very sweaty inside the kit and I feel dehydrated all the time since I do not drink anything despite sweating. We have to attend to patients continuously and there is no way I can remove it”, (Doctor, 26 yr old male).

-

“Wearing PPE kit for a long time makes me feel suffocated. It is just being covered up in a plastic bag. I feel breathless and I excessively sweat, but we have to face all this for our safety as well as for the society”, (Ambulance worker, 31 yr old male).

Fear of infection: ‘Fear’ was the most repeated word by all the respondents. Many HCWs expressed the fear of getting infected while carrying out their duties. This triggered stressful emotions as they faced the dilemma of diligently performing their duty of care haunted by this constant fear of getting infected. This fear of getting infected was also experienced by their peers who were not involved in COVID care duties who would avoid interacting with those HCWs involved in COVID care. This was unexpected considering that they all had patient care as their responsibility and could not afford to discriminate each other.

Family-related issues: The challenges that were family-related expressed by the majority of the participants included issues around separation (for long periods), lack of time, fear of infecting and non-disclosure of their COVID-19–related duties to their families.

Separation from families: All participants faced difficulty in balancing their work and family life. The most frequent issue reported was the long duration of separation from their families. Many reported the difficulties of long distance travel away from families, leaving them with a constant feeling of longing and sadness. There was also constant fear of losing their job if they did not agree to travel away from home for long periods as expected by them. This was particularly pronounced among women HCWs with infants and children who had to face challenges of caregiving being physically absent, as well as the fears associated with infecting their little ones who demanded their full attention when physically present at home. There was expression of remorse and guilt for being unable to function in their role as caregivers and providing care to their families, especially children, and fulfilling their household responsibilities.

-

“My work has affected my family life a lot. I stay in the quarters as required of me during this pandemic. I am not able to take care of my two yr old baby and leaving her was difficult for me. My kids are angry with me, and now whenever I call my daughter, she does not talk with me. They are angry because I have to leave them again and again. My elder daughter is studying in class 9, and as a mother, I should provide her more time in this growing up stage and I should help her with her studies, but I am unable to provide time for her. I am unable to provide them good food in these growing up years and I am unable to take care of them. It has been continuously 6 months now that I am facing this and I feel helpless I cannot make my family function better as a housewife would do”, [GNM (General Nursing & Midwifery), 43 yr old female].

No time with family: Most participants experienced great pressure with their busy schedules leaving them exhausted to even spend the available time with their family. For a few of them, working in such a situation was a necessity as they were responsible for financially supporting their family.

Fear of infecting and non-disclosure of COVID-19 duties to families: All participants expressed that their biggest concern was the risk of infecting their families with their exposure to COVID-19. This was more pronounced for HCWs who were staying with their families, who lived in perpetual fear of carrying infection home to their families, especially those family members with comorbid conditions.

“Since I am the one who is looking after my family, I am really scared about infecting them since I am involved in treating COVID-19 patients. I cannot even go back home these days as my parents are elderly. My father is a heart patient and a cancer survivor and my mother has recently undergone a spine surgery”, (Nurse, 47 yr old female).

Some participants concealed information related to their duties to avoid distressing their family members. In addition, they had to constantly assure them with regard to their safety and well-being, which was by itself stressful.

-

“I am living alone, away from my family, and I have not still told my family that I work in COVID-19 lab, as I do not want them to get upset and worried. I have not shared any of my hardships, my long working hours, instead, I have been having a normal conversation as though I have not been affected by any challenges during the COVID-19. It has been more than six months now and I have not told them nor do I want to tell them”, (Lab Technician, 28 yr old male).

Individual level: The impact of COVID-19 at the individual level has been mainly on the sense of well-being in many ways being which has been described under various sub-themes.

Sleep deprivation: The increase in workload with the long working hours has had an impact on their sleep cycle as described by most of the HCWs. Many of them also had an increased risk of sleep deprivation with the constant worry about work and experiences at work that affected their sleep even when they tried to sleep.

Disruption in eating habits: Another major problem expressed by all of them was the irregularity in their eating routine. Keeping up with regular meal times was not possible which led to various health problems. Many of them also reported that they had to skip eating food because of wearing the PPE kit for long hours.

Societal level:

Stigma and rejection: Experiences of stigma and rejection that resulted from caring for COVID-19 patients were reported by a majority of the HCWs. This was manifested in many ways. Most of them said that people around them (neighbours, friends and relatives) made them feel they were spreaders of COVID-19 infection and avoided them sometimes making hurtful remarks and also showed reluctance to interact with them. Some HCWs reported that they also had to conceal their identities to prevent any social harassment as captured in the statement below. There were also some who reported stigma from their own families.

“When people see me, they say “here comes corona!.” They (neighbours) would close their doors and windows if they saw me coming from a distance. At market places, people cover their faces when they see me. They would cross me or supersede me very fast by accelerating their vehicles. Even my relatives walk away when they see me and do not want to be face to face with me. There seems to be so much hatred in their minds”, (Ambulance driver, 55 yr old male).

Coping strategies adopted: In the wake of all the challenges HCWs faced the different coping strategies they adopted, were also corroborated.

Family and friends support: All participants reported that they could cope with the challenges they faced because of the support from their immediate family members and friends having another family member also engaged in COVID duty was a strong motivational force to deal with these tough times.

-

“My family is very supportive and they said that as I am doing the work related to COVID-19, I am getting an opportunity to contribute my service, and therefore, I should help as many people as I can”, (Doctor, 30 yr old male).

-

“My wife is also working in the hospital, she works in the ICU department, both of us support each other as we face these tough times together. We will work together, for this and whatever happens, we will face it together”, (Ambulance driver, 36 yr old male).

Peer support: A strong sense of support from colleagues was a powerful motivational force that helped them cope as reported by all participants. Many said that it was this sharing platform where many expressed similar hardships that were their strength which kept them motivated in difficult circumstances. Furthermore, some of them also appreciated the support they got from the higher authorities, which helped them fulfil their work-related responsibilities while ensuring their psychological well-being.

“We work as a team, so whenever we face a problem, we discuss it with the team. We bring out the best in each other, so whenever we feel demotivated or frustrated, we encourage each other”, (Doctor, 38 yr old male).

Spending time with self by listening to music/yoga/prayer: Many of the respondents said that their way of coping was their spiritual dependence, listening to music while some mentioned practicing yoga. Most of them opined that there was no time for any physical activity such as exercise or outdoor games with their work schedules, they had to think of managing their ‘me’ time within the confines of their workplace.

Positive experiences that helped cope and improve personal well-being: One of the coping mechanisms that emerged were the positive experiences amidst the hardships faced, which was manifested as appreciation and recognition for their contribution during the pandemic elevating their sense of worth and professional pride. Many participants expressed that they felt they did justice to their duty by serving others even if it was at the expense of risking their lives.

Suggestions on how to address the psychosocial impact due to COVID-19: There were various intervention strategies that HCWs suggested on how the psychosocial challenges they faced needed to be addressed. The same were classified into: (i) organizational level; (ii) societal level; and (iii) individual level challenges (Fig. 2). This included a conducive working environment involving periodic evaluation of the HCW problems, reduction in workload by rotation of workforce and engaging more staff, peer support services and political support. At the societal level, it was mainly on mitigating stigma by the powerful role of the media in providing the right information, community and HCW involvement in COVID sensitization to allay the fears associated with COVID-19 infection and transmission. This would lessen the tendency to view HCWs as a potential source of infection and promote positive attitudes toward them. Finally, at the individual level, the call was for need-based psychological support for them and their families.

Discussion

This study provides insights into the different psychosocial dimensions which have impacted HCWs as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. First, the study findings point to the challenges at the organizational level which is reflected in the major changes in the working culture of HCWs who were ill-prepared for this change. This included a paradigm shift across different duties and additional responsibilities apart from their usual routine. Recent reports indicate that health personnel struggled with higher workloads and a swiftly changing workspace milieu that differed greatly from the familiar day-to-day reality while dealing with the social changes and emotional stressors of COVID-191920. The longer working hours with erratic timings reported in the present study resulted in sleep deprivation as well as unhealthy eating patterns, which could have long-term consequences. Earlier studies reported the psychological distress faced by HCWs as a result of disruption in sleep pattern and insomnia2122.

Furthermore, our study findings highlight the challenges associated with following the protection protocol that HCWs in COVID-19 care management have to follow that mandates a protection gear (PPE) and the additional protocol of quarantine after performing their duties. While these precautions are aimed to protect themselves the impact, it has on them from practical to physical discomfort, such as lack of hydration and inability to relieve themselves is worrisome. This finding was similar to another study that reported that long work shifts with poor infrastructure and the requirement of wearing PPE caused physical uneasiness including breathing difficulty amongst the HCWs23.

Another salient finding with regard to their work environment was the fear of infecting themselves experienced across all tiers of health care personnel with the constant exposure to COVID-19–infected individuals. This fear many a time interfered with the ability to offer quality and adequate humane care which is expected of HCWs, however, the challenges of providing care through a highly transmissible pandemic of this nature seemed to push the limits of their tolerance.

Secondly, the study findings point to the impact on families that had a dual impact as HCWs were adversely affected staying away from their respective families and the families affected because of the long separation and the protocol measures of being involved in COVID-19 care duties. The fear of infecting their families was far higher than the fear of being infected themselves. This fear had an impact on their families who often failed to understand why they behaved differently by either isolating themselves or staying away for long periods. This was more pronounced among female HCWs with varied levels of impact especially on the children as they tried to balance both work and family life. This resulted in, women having to experience the triple burden of being caregivers in the hospital, at home and balancing these dual roles which took a toll on their mental well-being as also reported earlier13242526.

Third, the psychosocial impact was largely societal especially with the stigma and rejection that HCWs often faced indirectly impacting their families as well as forcing some of them to conceal their identities. This attitude was mainly because they were considered as vectors for transmission of the virus and not perceived as those whose primary service was to prevent infection and help those infected. This often resulted in pushing some HCWs to conceal their identities in order to prevent any social harassment. These findings are similar to the finding from the study on Canadian health professionals who not only felt fear -contagion for themselves during the 2003 SARS epidemic but also avoided identifying themselves as HCWs due to stigmatization within their communities27. Another manifestation of stigma was exhibited as avoidance even among their peers working in non-COVID-19 care similar to a previous report22.

The fourth salient finding was, the coping strategies adopted by HCWs against the challenges they faced. The drivers for coping were both extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic was related to the appreciation they received for their contribution in such unprecedented times, resulting in a sense of productivity and professional pride increasing their feeling of self worth. Solace in spiritual belief systems was a strong coping mechanism apart from peer and family support. Studies have also shown that peer support or support from loved ones for physicians led to less burnout experiences among them as compared to others without support2.

Previous studies among nurses involved in patient care during severe disease outbreaks also focused on the role of self-care activities such as workout, meditation, music and listening to podcasts for coping with the stress and improved psychological well-being during the crisis2829.

The above study findings conclude that HCWs at all levels involved in COVID-19 care services face various challenges in their work–life, family life affecting their sense of well-being in many distinct ways. The study further provides insight into the interventions as perceived by HCWs to address these psychosocial challenges at the organisational, societal and individual level (Fig. 3).

- Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 and multisectoral interventions.

This study was not without its limitations. The limited time period to complete the study and the need for telephonic interviewing as compared to the preferred face-to-face interviews (especially in the collection of qualitative data) was a limiting factor especially since it was done keeping in mind that the work schedule or family time of the HCWs was not compromised. Several field realities were faced in this context, especially with regards to fixing appointments, network issues, the right place of interviewing with privacy and the challenge of building trust over the telephone. Another limitation was the need to rely on purposive sampling given the difficulties in reaching this target population in the stipulated time period. Considering that HCWs are mainly females at most levels, our study was not able to adequately capture the gender differences in facing the various psychosocial challenges described. This could be an area for further research as more insight could be gained on the gender focused psychosocial interventions to address these challenges.

Overall, the study findings call for interventions requiring a layered response, comprising strategies and actions that are structural, societal and at the individual level. There is a need to shift from the focus on provision of psychological services (which is often the recommended strategy) to need-based interventions at the organization level. This includes the provision of a supportive environment from the management to address the present new norm of work routine. This proactive intervention would help prevent the adverse psychosocial impact rather than deal with it by providing psychological services following the impact suffered. Second, the need for inclusiveness of the families of HCWs in support services which is key to the mental health and well-being of the HCWs. This is most often overlooked. Third, the need for intervention at the societal level with the provision of right information through the social and print media, inclusion of HCWs as a core group in COVID sensitization strategies to allay the unfounded fears associated with COVID-19 and for better acceptability of HCWs. These interventions could help improve the mental well being of HCWs as they cope with the various psychosocial challenges associated with their involvement in COVID-19 management.

Financial support & sponsorship: This study was funded by the ICMR, New Delhi, through the National Task Force for COVID-19.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Current status of epidemiology, diagnosis, therapeutics, and vaccines for novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;30:313-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8:E421.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e253.

- [Google Scholar]

- China empowers Internet hospital to fight against COVID-19. J Infect. 2020;81:e67-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mental health burden of frontline health professionals treating imported patients with COVID-19 in China during the pandemic. Psychol Med 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002093

- [Google Scholar]

- Feeling the early impact of COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health of nurses in India. J Dep Anxiety. 2020;9:381.

- [Google Scholar]

- Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:144-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- Stigma: The Other Enemy India's Overworked Doctors Face in the Battle against COVID-19. Quartz India. Available from: https://qz.com/india/1824866/indian-doctors-fighting-coronavirus-now-face-social-stigma/

- [Google Scholar]

- Doctors in India evicted from their homes as coronavirus fear spreads. CNN. Available from: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/25/asia/india-coronavirus-doctors-discrimination-intl-hnk/index.html

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 and women's triple burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Soc Sci. 2020;9:87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in India: An observational study. Fam Med Prim Care. 2020;9:5921-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stress, sleep and psychological impact in healthcare workers during the early phase of COVID-19 in India: A factor analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:611314.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 outbreak: Impact on psychological well- being of the health-care workers of a designated COVID-19 hospital. J Mental Health Hum Behav. 2021;26:20-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of psychological impact of COVID-19 on health-care workers. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021;63:222-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods Vol 3. (3rd ed). New Delhi: Sage Publications; 2003. p. :60-1.

- Life in the pandemic: Some reflections on nursing in the context of COVID-19. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:2041-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:2133-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative study of the psychological experiences of health care workers during the COVID 19 pandemic. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;37:93-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian J Psychiatry. 2020;42:232-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The multifaceted impact of COVID-19 on the female academic emergency physician: A national conversation. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:91-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in India: Results of a questionnaire-based survey. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:664-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic stress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1117-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative study: Experienced of caregivers during COVID19. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on the psychological needs of nurses caring for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 from the perspective of the existence, relatedness, and growth theory. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7:157-60.

- [Google Scholar]