Translate this page into:

Prevalence & factors associated with chronic obstetric morbidities in Nashik district, Maharashtra, India

Reprint requests: Dr Ragini Kulkarni, Department of Operational Research, National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health (ICMR), Jehangir Merwanjee Street, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, Maharashtra, India e-mail: nirrhdor@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

In India, community based data on chronic obstetric morbidities (COM) are scanty and largely derived from hospital records. The main aim of the study was to assess the community based prevalence and the factors associated with the defined COM - obstetric fistula, genital prolapse, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and secondary infertility among women in Nashik district of Maharashtra State, India.

Methods:

The study was cross-sectional with self-reports followed by clinical and gynaecological examination. Six primary health centre areas in Nashik district were selected by systematic random sampling. Six months were spent on rapport development with the community following which household interviews were conducted among 1560 women and they were mobilized to attend health facility for clinical examination.

Results:

Of the 1560 women interviewed at household level, 1167 women volunteered to undergo clinical examination giving a response rate of 75 per cent. The prevalence of defined COM among 1167 women was genital prolapse (7.1%), chronic PID (2.5%), secondary infertility (1.7%) and fistula (0.08%). Advancing age, illiteracy, high parity, conduction of deliveries by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and obesity were significantly associated with the occurrence of genital prolapse. History of at least one abortion was significantly associated with secondary infertility. Chronic PID had no significant association with any of the socio-demographic or obstetric factors.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study findings provided an insight in the magnitude of community-based prevalence of COM and the factors associated with it. The results showed that COM were prevalent among women which could be addressed by interventions at personal, social and health services delivery level.

Keywords

Chronic obstetric morbidities

chronic PID

community-based prevalence

genital prolapse

obstetric fistula

secondary infertility

Reproductive morbidities include gynaecologic and obstetric morbidities. Gynaecologic morbidities include reproductive tract infections, menstrual disorders, reproductive endocrinal disorders and primary infertility. Obstetric morbidities are related to pregnancy, delivery or treatment of conditions that arise during pregnancy or delivery. These can be acute and chronic. The short term or acute morbidities occur during pregnancy, delivery or within six months of delivery or abortion and include eclampsia, antepartum and postpartum haemorrhage, obstructed labour, sepsis and post abortion bleeding or sepsis. The long term or chronic obstetric morbidities (COM) include obstetric fistula (vesico-vaginal or recto-vaginal), genital prolapse, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and secondary infertility1.

Many studies have been conducted to estimate the prevalence and determinants of gynaecological morbidities globally and in India23456789. Data on self reported experiences on acute obstetric morbidities in India are also available from the National Family Health Survey conducted in 1998-199910 and 2005-2006 in the country11. However, chronic obstetric morbidities (COM) is a neglected issue in India. The available data on COM are scanty and largely derived from hospital records. Considering the need for such information, the present study was undertaken to assess the magnitude and the factors associated with defined COM such as obstetric fistula, genital prolapse, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and secondary infertility in Nashik district of Maharashtra State of India. In addition, information on associated factors such as demographic, socio-economic and factors related to conduction of deliveries and abortions was also collected. Though the focus of the study was on COM, the opportunity was utilized for collecting data on gynaecological morbidities also.

Material & Methods

The protocol of this community based cross-sectional study was approved from Institutional Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health, Mumbai, India. Written informed consent in local language was obtained from the respondent during household survey, facility based survey and clinical examination.

The study was conducted during two years between January 2006 and December 2007 in Nashik district of Maharashtra. Selection of district was done based on the data of indicators such as percentage of girls married at age less than 18 yr, home deliveries and institutional deliveries for 33 districts in Maharashtra state as per the District Level Household Survey (DLHS III) conducted in 2002-200312. As per these data, Nashik district had its indicators at mid-level and hence was selected to represent the Maharashtra State. For appropriate representation of the rural population from the district, the list of total 103 primary health centres (PHCs) consisting of 52 tribal and 51 non-tribal PHCs was obtained from the District Health Office. Six PHC areas (3 each from tribal and non-tribal) were selected by systematic random sampling. One village each from the PHC and subcentre was selected and 130 women satisfying the inclusion criteria were selected by visiting households. Thus, from each PHC, 260 women leading to a total of 1560 women from six PHCs were included in the study.

The existing data on prevalence from the community-based studies conducted on chronic obstetric morbidities in South-Asia13 was considered for estimation of sample size in the study. Considering the lowest prevalent condition of obstetric fistula as

one per cent, the sample size for infinite population was calculated to be 1560 women. An expected sample loss of 45 per cent was considered for calculation of sample size. The studies conducted in India in rural setting had shown a response rate varying from 19-59 per cent3567. Hence an anticipated sample loss of 45 per cent was taken.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria for study participation were non-pregnant ever married women with proven fertility (had at least one abortion or live birth or stillbirth) in the age group of 15-44 yr. The exclusion criteria were pregnant women, women who had delivered or had abortion within last six months and women having history of hysterectomy.

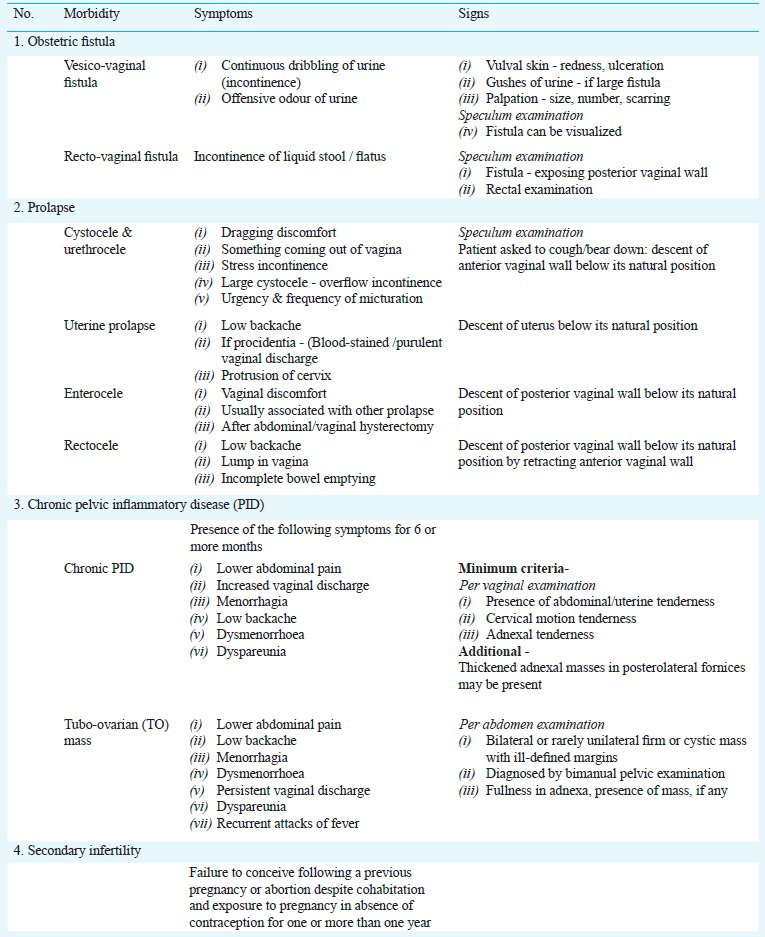

Tools including the women's household interview schedule and clinic schedule were drafted by the investigators; the draft was discussed and finalized with United Nations Population Fund - India (UNFPA) technical advisory group members. Operational definitions with diagnostic clinical criteria for defined COM (obstetric fistula, genital prolapse, chronic PID and secondary infertility) were framed14, discussed and adopted during an expert group meeting at UNFPA, Delhi (Annexure). Pre-testing of tools was done in the field areas and these were finalized in two expert group meetings.

Data collection: Prior to data collection, rapport building efforts were done extensively in the community for six months to create a conducive environment to maximize women's participation in the study. Close interaction with the government health staff, stakeholders such as local leaders including panchayat members and mahila mandals (women's groups) was also done. Qualitative as well as quantitative methods were used for data collection. Six focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted among ever married non-pregnant women in reproductive age group one in each PHC area to explore the awareness, perceptions and experiences related to reproductive morbidities, the coping mechanism and treatment seeking behaviour for these morbidities. FGDs also helped in understanding the local terminologies for these morbidities and designing the questionnaire. This was followed by collection of quantitative data by social investigators during household interviews among 1560 women. These women were mobilized by special efforts in the community such as conducting communication activities for maximum participation of women for undergoing clinical examination at the medical camps organized at the health facility (PHC or Subcentre).

Of the 1560 women interviewed at household level, 1217 women came for the medical camps organized at the PHCs or Subcentres. Of the 1217 women, 50 women did not give consent to undergo clinical examination for reasons such as shyness, fear to get examined and not having any health problems. Therefore, interviews were conducted by gynaecologists among the willing 1167 women followed by clinical, per speculum and per vaginal examination. Of the 1560 women, 1167 women had their complete participation in the study resulting in a response rate of 75 per cent.

Statistical analysis: Data entry was done in the EPI-6 statistical software (CDC, Atlanta, USA). Data were cleaned after scrutinizing for errors, omissions and discrepancies. SPSS-PC version 12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used for analyzing the data. Chi-square test was carried out to study the difference between proportions. Fisher's exact test was applied in case where the expected frequency was less than five in any of the cell.

Results

Of the 1560 women, 1167 (75%) completed the study processes including clinical examination. The reasons for non-participation of 393 women were asymptomatic women not willing to undergo examination, not satisfied with treatment of PHC, busy with work and women unwilling to lose their daily wages. Treatment was given to majority of women diagnosed with morbidities after conduction of clinical and gynecological examination and wherever required women were advised investigations and were referred to higher facilities for treatment with a back up of follow up.

Mean age of women at the time of household interview was 31 ± 7.09 yr, 249 (21.3% were between 15-24 yr age group; 518 (44.4%) between 25-34 yr age group; and 400 (34.3%) were above 35 yr. One hundred and ninty six (94%) women were currently married while the rest were widows, separated or divorced. Fifty one per cent women were staying in nuclear families and almost two third 823 (70.5%) households had monthly per capita income of less than  500. Majority of women were Hindus 1119 (95.8%) and 623 (53.4%) belonged to scheduled tribes. About half 564 (48.4%) of the participants were illiterates, 154 (13.2%) had primary education and 449 (38.4%) had secondary and above education. Majority, 957 (82%) were working and were engaged in some kind of economic activity while only 210 (18%) were housewives. Of the working women, majority 725 (75.7%) were engaged in unskilled occupation. Nine hundred and seventy four (83.4%) women reported that they got married before 18 yr of age and 844 (72.3%) had first pregnancy when they were less than 18 yr.

500. Majority of women were Hindus 1119 (95.8%) and 623 (53.4%) belonged to scheduled tribes. About half 564 (48.4%) of the participants were illiterates, 154 (13.2%) had primary education and 449 (38.4%) had secondary and above education. Majority, 957 (82%) were working and were engaged in some kind of economic activity while only 210 (18%) were housewives. Of the working women, majority 725 (75.7%) were engaged in unskilled occupation. Nine hundred and seventy four (83.4%) women reported that they got married before 18 yr of age and 844 (72.3%) had first pregnancy when they were less than 18 yr.

About two third i.e. 762 (65.3%) women reported that they had more than three pregnancies. The outcome of reported 3939 pregnancies among 1167 women indicated that 3565 (90.4%) were live births, 332 (8.5%) were abortions, (2 pregnancies) 0.05 per cent were ectopic while 40 (1%) were stillbirths. Of the 3605 reported deliveries in these women, 3542 (98.2%) were vaginal deliveries while 63 (1.4%) were caesarean sections and mostly (79.2%) deliveries were conducted at home. Seventy per cent deliveries were conducted by Dais (Traditional Birth Attendants-TBA), 594 (16.5%) per cent by doctors and 410 (11.4%) by auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs). Among the deliveries, complications were reported in 297 deliveries (8.24%), the commonest being prolonged labour followed by post-partum haemorrhage and perineal tear. Out of 332 abortions, 222 (67%) were spontaneous while 110 (33%) were induced in nature. Among spontaneous abortions, 93 (42%) occurred at hospital/health centre and 129 (58%) occurred at home. Among these abortions, 65 (29.2%) did not seek any treatment. Among the induced abortions, majority 95 (86.7%) were conducted at hospital/health centre and 15 (12.4%) at home. Majority of the induced abortions 95 (86%) were conducted by doctors, 9 (8.2%) by ANMs and 6 (5.5%) by others. Among these abortions, maximum symptoms were lower abdominal pain 31 (28.6%) followed by fever 28 (25.7%) and excessive bleeding 25 (22.8%).

The general examination of the 1167 women during medical camps revealed that 438 (37%) women had signs of anaemia (pallor on clinical examination), 364 (31%) women were underweight (BMI < 17.99 kg/m2, 651 (55%) were in normal range (BMI 18-22.9 kg/m2, 64 (4%) were overweight (BMI 23-24.99 kg/m2 and only 88 (7%) were obese (BMI- above 25 kg/m2 as per the definition15. On enquiry of family planning method usage, 268 (23%) women reported non use of any contraceptive method. Among the 899 (77%) who had ever used contraceptive methods, 758 (84.3%) had undergone tubectomy, 81 (9%) reported that their husbands had undergone vasectomy, 24 (2.6%) used oral pills and condoms each, 11 (1.2%) had IUCD insertion, 1 (0.1%) used other natural methods such as withdrawal.

The socio-demographic characteristics and the obstetric history of the remaining (25%) women interviewed at household level but who did not undergo clinical examination (n= 393) was similar to the women who underwent clinical examination.

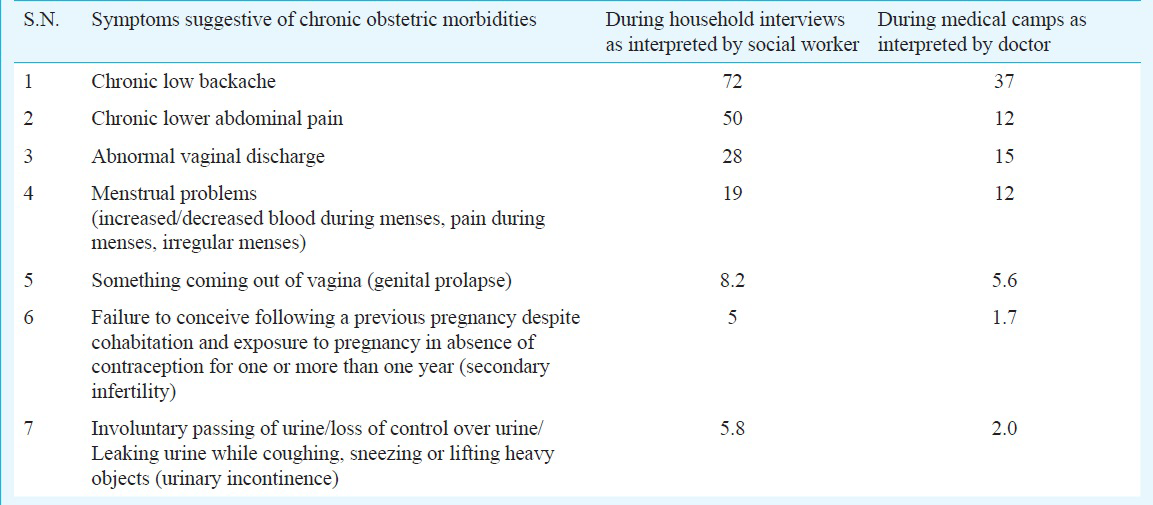

Prevalence of defined chronic obstetric morbidities on the basis of symptoms: Self reported symptoms among women interviewed at household level and women who underwent clinical examination interpreted by social worker and doctor are presented in Table I. Chronic low backache and lower abdominal pain reported and interpreted by doctors was much lower as compared to the social workers. The difference in interpretation for other symptoms such as abnormal vaginal discharge, menstrual problems, genital prolapse, secondary infertility and urinary incontinence was much lower.

Prevalence of defined reproductive, gynecological and chronic obstetric morbidities on clinical examination: Of the 1167 women who underwent clinical examination, 509 (44%) women were detected with reproductive morbidities while 658 (56%) were not found to have any reproductive morbidity. The detected reproductive morbidities included 373 (32%) women with gynaecological morbidities and 136 (12%) with chronic obstetric morbidities (COM). Among this subset of 136 COM, genital prolapse was found to be most prevalent 84 (62%), followed by chronic PID 30 (22%), secondary infertility 21 (15%) and vesico-vaginal fistula 1 (1%). The prevalence of major gynaecological morbidities were genital candidiasis 102 (8.7%), vaginitis 91 (7.8%), cervical erosion 61 (5.2%); and cervicitis 45 (3.9%). The prevalence of defined COM among the 1167 women were genital prolapsed 84 (7.1%), chronic PID 30 (2.5%), secondary infertility 21 (1.7%), and vesico-vaginal fistula 1 (0.08%). Twenty five (5%) of 509 women detected with any reproductive morbidity had more than one morbidity. The overall prevalence of reproductive morbidities was 1.1 per woman. (COM - 1 per woman and gynaecological morbidity - 1.1 per woman).

Factors associated with defined chronic obstetric morbidities:

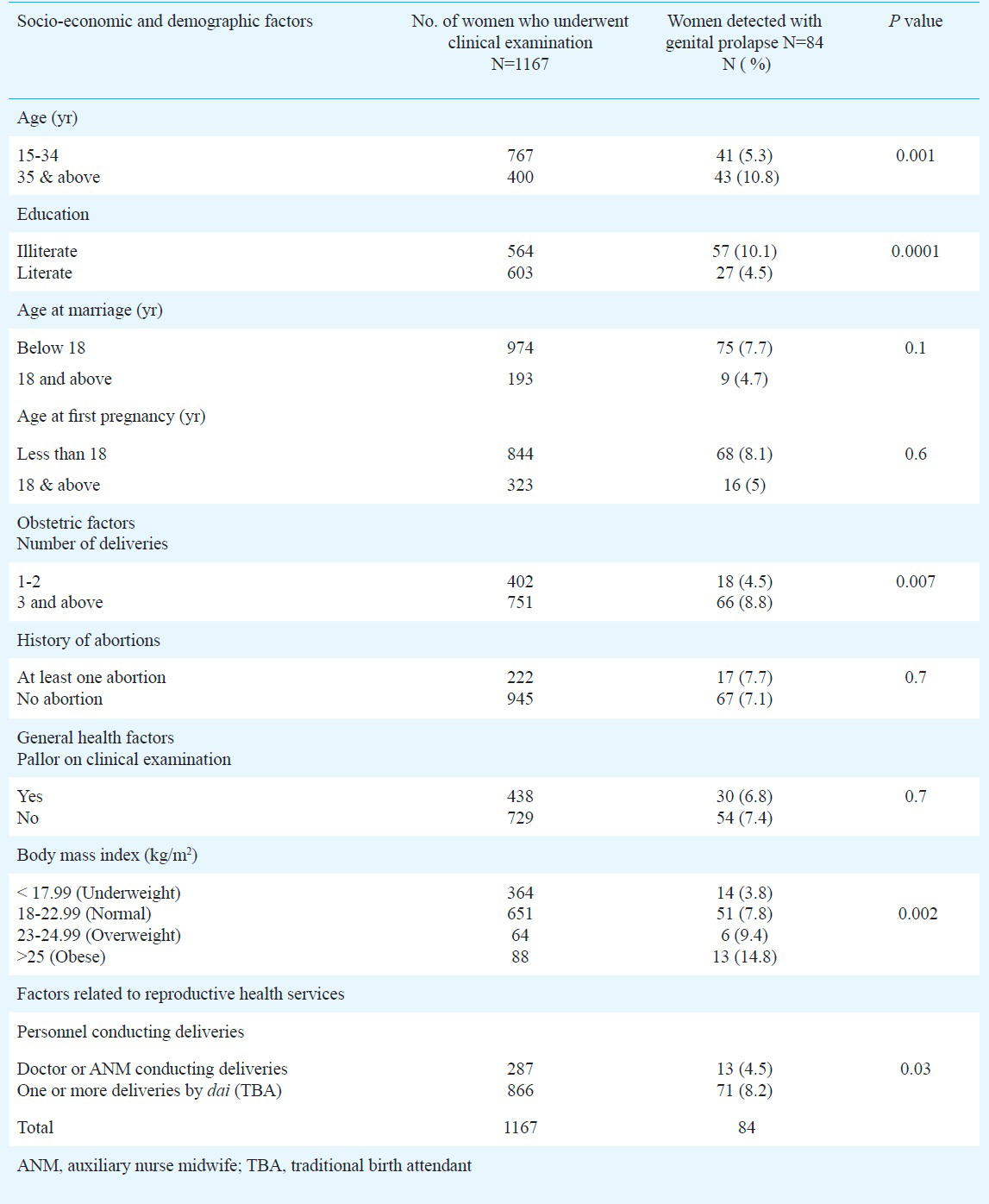

Genital prolapse - Of the 84 cases detected with genital prolapse, 46 (55%) were first degree, 23 (27%) were second degree, nine (11%) were third degree, four (5%) were with cystocele and two (2%) were procedentia. Socio-economic and demographic factors such as advancing age and illiteracy were found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of prolapse. In addition, overweight and obesity, obstetric factors such as high parity and deliveries conducted by traditional birth attendants (TBA) were significantly associated with the occurrence of prolapse (Table II). Though early age at marriage was not significantly associated with the occurrence of genital prolapse, the percentage of women detected with genital prolapse (7.7%) was more in women married below 18 yr as compared to 4.7 per cent whose age at marriage was 18 yr and above (Table II).

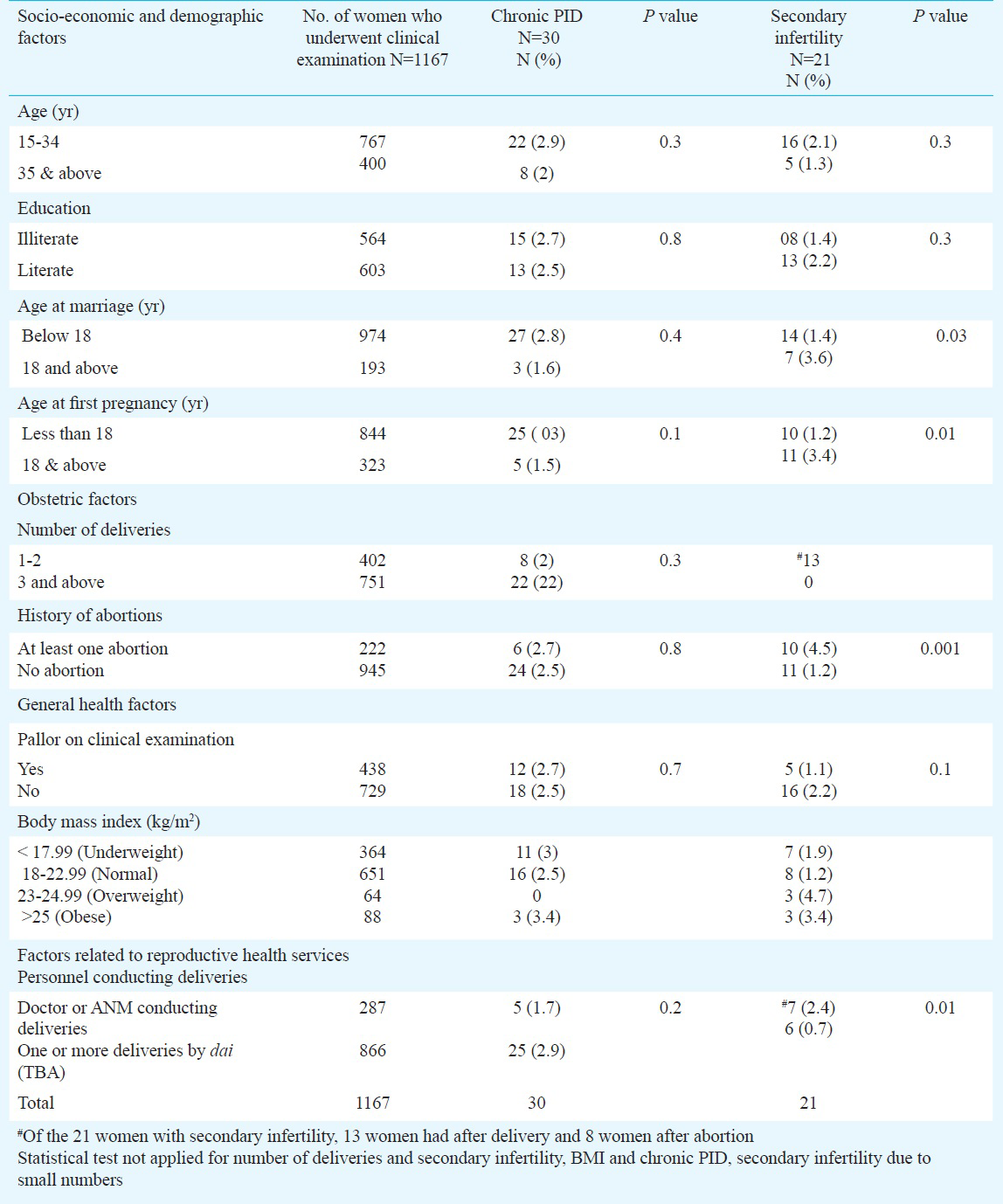

Chronic PID - Of the 30 cases of chronic PID, only two (7%) were diagnosed with tubo-ovarian mass. Socio-demographic, general health factors and factors related to reproductive health services were not found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of chronic PID. The percentage of women with high parity (3 and above) was higher (22%) in women detected with chronic PID as compared to women having 1-2 deliveries (2%) (Table III). Among 30 women with chronic PID, five reported of puerperal sepsis during last delivery.

Secondary infertility - Socio-economic factors such as age and education did not show any significant association with the occurrence of secondary infertility in women. Factors such as higher age at marriage and first pregnancy were significantly associated with the occurrence of secondary infertility. Of the 21 women with secondary infertility, 13 had it after delivery and eight after abortion. Percentage of women with secondary infertility was more in women having at least one abortion as compared with women with no history of abortion and this association was found to be significant (Table III). Among the six women in whom, deliveries were conducted by TBAs, two gave history suggestive of puerperal sepsis. Among women having abortions, four women reported history suggestive of post-abortion sepsis, of whom in two women, abortions were conducted by TBAs.

Statistical test was not applied for studying the association of BMI with chronic PID and secondary infertility due to small numbers of detected cases of these morbidities.

Obstetric fistula - Only one case of vesico-vaginal fistula was detected in a 28 yr old woman, suffering from involuntary passage of urine since last eight years. The fistula occurred due to obstructed labour and lack of transport during labour to higher level health facilities. Her domestic, social and economic activities were severely affected due to fistula. She was operated at the district hospital, Nashik as a part of treatment and follow up of the study participation and was relieved of the symptoms of urinary incontinence.

Discussion

In the present study the overall prevalence of genital prolapse was 7.1 per cent and was the most prevalent morbidity (62%) among the COM as per clinical examination. The other eight community based studies in India have reported the prevalence of prolapse between less than one to 27 per cent16. The results of a multi-centre studies carried out in Egypt and Jordan found prevalence of prolapse as 56.3 and 34.1 per cent, respectively29. The mean prevalence for prolapse was reported as 19.7 per cent (3.4-56.4%) and urinary incontinence as 7 per cent (5.3- 41%) in a review of thirty studies between 1989 to 200717. In our study, advancing age, illiteracy, obesity and high parity were found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of prolapsed as shown in other studies218.

A community based cross-sectional study conducted in urban area of Belgaum, Karnataka, determined the prevalence of gynaecological problems among 400 married women of the reproductive age group19. A high prevalence of reproductive tract infections (70%) was also detected among these women. This included 24.25 per cent detected with chronic PID. This was higher as compared to that reported in our study (2.5%); however, the study in Belgaum was conducted in an urban area and the associated factors for such high a prevalence of chronic PID were not explained.

History of puerperal sepsis during the last delivery was indicative for occurrence of chronic PID in five women. Though socio-demographic, general health factors and factors related to reproductive health services were not found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of chronic PID; the number of women suffering from chronic PID was relatively small to study this association.

The prevalence of secondary infertility has been reported to be 9.2 per cent in Nigeria20; 26.5 to 18.9 per cent in Central Africa21 and 12.9 per cent in West Siberia22. In some of these countries, socio-economic and regional factors also play a role in addition to genital infections. In India there are hardly any community based studies conducted in which prevalence of secondary infertility is estimated. In a study conducted in Belgaum, Karnataka, 2.75 per cent women reported secondary infertility19 which was higher (1.7%) as compared to that reported in the present study. As per report of a large country wide survey (DLHS-III)23 conducted in 2007, 2 and 1.2 per cent women reported having secondary infertility problem in Maharashtra and Nashik, respectively. In the present study, self reported prevalence of secondary infertility was 5 per cent.

In the present study, 2 per cent of women reported incontinence of urine. Except for one woman who reported continuous leaking of urine and was diagnosed with vesico-vaginal fistula, other women reported symptoms suggestive of stress incontinence. Though stress incontinence of urine is a common problem among women, the lesser number of women reporting it in the present study could be due to exclusion of pregnant women, menopausal women and women with hysterectomy.

Majority of studies conducted for estimation of obstetric fistula prevalence globally and in India are hospital based. A WHO review on obstetric fistula showed that the highest percentage of fistula for gynaecological admissions was 16.4 per cent reported in Sudan24. The prevalence of obstetric fistula was 1 per 1000 women in a hospital based study in Kenya25. Prolonged labour, age, level of education, parity, occupation, severe female genital mutilation, lack of access to transport and primary health care in the rural community and early marriage were characteristics of the fistula patients25. The prevalence of obstetric fistula was very low (0.08%) in our study, but it was a community based study so the results were not comparable. History of prolonged labour, illiteracy, lack of access to transport were reported in the woman diagnosed with vesico- vaginal fistula.

A retrospective hospital-based prevalence study on obstetric fistula conducted in India indicated that the commonest type of fistula was genitourinary (86.6%), rectovaginal (12.1%), and both as 1.2 per cent26. In Bangladesh, the prevalence of fistula was found to be 1.69 cases per 1000 ever-married women13.

In a systematic review conducted by Adler et al27 19 population based studies to estimate prevalence of obstetric fistula were included. The pooled prevalence in these studies was 1.20 per 1000 women in South Asia. In a cross-sectional study conducted in south India5, the prevalence of obstetric fistula was 2.6 per cent which was higher compared to the present study. The community based prevalence of obstetric fistula was 1.6 per cent among rural women in Maharashtra23. This indicates that over-reporting of obstetric fistula may occur if relied only on the interview based method. Clinical examination for the diagnosis of obstetric fistula is essential in community based surveys.

Our study had certain limitations. The study was conducted among women in a population of low socio-economic status and, therefore, the resutls could not be generalized to the population of the district. As we have included one sixth of the total sample of women from one PHC, there is a possibility of clustering effect due to exposure of these women to same social, environmental and facility conditions.

In conclusion, our study provided community-based prevalence data on COM and an insight on the factors associated with it. It was found that the COMs were prevalent among the women studied which could be addressed by interventions at personal, social and health system delivery level.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA) for providing technical and financial support to the study. The authors thank Dr Shahina Begum, Scientist C, Department of Biostatistics, National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health, Mumbai, for statistical consultation of data and Dr Smita Sope hired on the project, for conducting gynaecological examination of women during the medical camps conducted during the study.

References

- Reproductive morbidity: a conceptual framework. Family Health International Working Papers, No. WP95-02; September 1995 Research Triangle Park, Durham, NC. 1995

- [Google Scholar]

- A community study of gynecological and related morbidities in rural Egypt. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24:175-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of gynaecological diseases in rural Indian women. Lancet. 1989;1:85-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of self reported symptoms of gynecological morbidity with clinical and laboratory diagnosis in a New Delhi slum. Asia Pac Popul J. 2001;16:75-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Levels and determinants of gynecological morbidity in a district of south India. Stud Fam Plann. 1997;28:95-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). A baseline survey of reproductive health services in 23 districts (14 states) of India - a component of Modified District Project. New Delhi: ICMR; 1997.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of clinically detectable gynaecological morbidity in India: results of four community based studies. J Fam Welfare. 1997;43:8-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigating women's gynecological morbidity in India: not just another KAP survey. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;6:84-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring reproductive morbidity: a community based approach, Jordan. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24:635-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. In: National family health survey (NFHS-2), 1998-99. India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. In: National family health survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India. Vol II. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) In: District level household survey (DLHS-2), 2002-04: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- UNFPA. Report of the South Asia conference for the prevention and treatment of obstetric fistula. December 9-11. 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- A decade of research on reproductive tract infections and other gynecological morbidy in India: What we know and what we don’t know. In: Ramasubban R, Jejeebhoy SJ, eds. Women's reproductive health in India. Jaipur: Rawat Publications; 2000. p. :236-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in developing countries: review of prevalence and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:127-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gynecological problems of married women in the reproductive age group of urban Belgaum, Karnataka. Al Ameen J Med Sci. 2013;6:226-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of infertility in a rural Nigerian community. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1991;20:23-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the prevalence and causes of infertility in western Siberia. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:183-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) In: District level household and facility survey (DLHS-3), 2007-08: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological determinants of vesicovaginal fistulas. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90:387.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of women admitted with obstetric fistula in the rural hospitals in West Pokot, Kenya. Postgraduate Training Course in Reproductive Health, Geneva. 2004. Available from: www.gfmer.ch/Medical_education_En/…/Obstetric_fistula_Kenya.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Obstetric fistula in India: current scenario. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:1403-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimating the prevalence of obstetric fistula: a systematic review and meta analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:246.

- [Google Scholar]

Annexure: Clinical criteria for diagnosis of chronic obstetric morbidities