Translate this page into:

Occurrence of osteoporosis & factors determining bone mineral loss in young adults with Graves’ disease

Reprint requests: Dr Deep Dutta, Room-9A, 4th Floor, Ronald Ross Building, Department of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education & Research & Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, 244 AJC Bose Road, Kolkata 700 020, West Bengal, India E-mail: deepdutta2000@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

There is a paucity of data with conflicting reports regarding the extent and pattern of bone mineral (BM) loss in Graves’ disease (GD), especially in young adults. Also, interpretation of BM data in Indians is limited by use of T-score cut-offs derived from Caucasians. This study was aimed to evaluate the occurrence of osteoporosis in active treatment naive patients with GD and determine the factors predicting BM loss, using standard T-scores from Caucasians and compare with the cut-offs proposed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for diagnosing osteoporosis in Indians.

Methods:

Patients with GD, >20 yr age without any history of use of anti-thyroid drugs, and normal controls without fracture history, drugs use or co-morbidities underwent BM density (BMD) assessment at lumbar spine, hip and forearm, thyroid function and calcium profile assessment. Women with menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency and men with androgen deficiency were excluded.

Results:

Patients with GD (n=31) had significantly lower BMD at spine (1.01±0.10 vs. 1.13±0.16 g/cm2), hip (0.88±0.10 vs. 1.04±0.19 g/cm2) and forearm (0.46±0.04 vs. 0.59±0.09 g/cm2) compared with controls (n=30) (P<0.001). Nine (29%) and six (19.3%) patients with GD had osteoporosis as per T-score and ICMR criteria, respectively. None of GD patients had osteoporosis at hip or spine as per ICMR criteria. Serum T3 had strongest inverse correlation with BMD at spine, hip and femur. Step-wise linear regression analysis after adjusting for age, BMI and vitamin D showed T3 to be the best predictor of reduced BMD at spine, hip and forearm, followed by phosphate at forearm and 48 h I131 uptake for spine BMD in GD.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Osteoporosis at hip or spine is not a major problem in GD and more commonly involves forearm. Diagnostic criterion developed from Caucasians tends to overdiagnose osteoporosis in Indians. T3 elevation and phosphate are important predictors of BMD. Baseline I131 uptake may have some role in predicting BMD.

Keywords

Bone mineral density

Graves’ disease

osteoporosis

radioiodine uptake

Thyroid bone disease is a high turn-over disease characterized by increased osteoblast and osteoclast activity1, increased circulating and urinary levels of bone formation (alkaline phosphate, osteocalcin) and resorption markers (hydroxyproline, pyridinoline and deoxypyridinoline), with a predominant increase in the resorption markers2, resulting in mild hypercalcemia which may be observed in as many as 27 per cent of hyperthyroid individuals1. Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) itself has a trophic action on bone, with an enhancing effect on the osteoblasts accompanied by a negative effect on the osteoclasts, which is attenuated in thyrotoxicosis due to suppressed TSH34. Plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD) levels are decreased in hyperthyroidism which may contribute to bone loss1. Hence bone mineral loss in hyperthyroidism is multifactorial, and is an important cause of the associated increased risk of fracture5. However, the factors which determine this bone loss have not been well studied among Indians.

Densitometric studies have revealed decreased bone mineral density (BMD) at spine, femur, radius and total body in hyperthyroid patients6. Assessment of BMD in hyperthyroidism has traditionally been recommended for cortical bones7. Graves’ disease (GD) is the most common cause of thyrotoxicosis constituting 50-80 per cent of all cases1. There is a paucity of data regarding the pattern of bone mineral loss in GD with a few studies suggesting a predominant involvement of the cortical bone (radius and femur)8, while others suggesting a predominant involvement of the cancellous bone (spine)9. Most of these data are available from geriatric patients complicated by menopause and male androgen deficiency. Pattern of bone mineral loss among young adults with Graves’ disease in India is not known. Also, interpretation of bone mineral loss data from dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) among Indians is limited by use of cut-off values derived from Caucasians, which tend to overdiagnose osteoporosis1011. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has proposed cut-off values for diagnosing osteoporosis in Indians12.

This study was aimed to determine the BMD in young adults with active treatment naive GD at lumbar spine, hip and forearm and compare it to age matched euthyroid controls, and to evaluate the occurrence of osteoporosis in these patients as per the ICMR criteria comparing with the T-score cut-offs commonly used (derived from Caucasians). It was also planned to evaluate whether commonly assessed clinical (duration of disease) and biochemical (severity of thyrotoxicosis) parameters and I131 uptake in GD could predict the severity of bone mineral loss.

Material & Methods

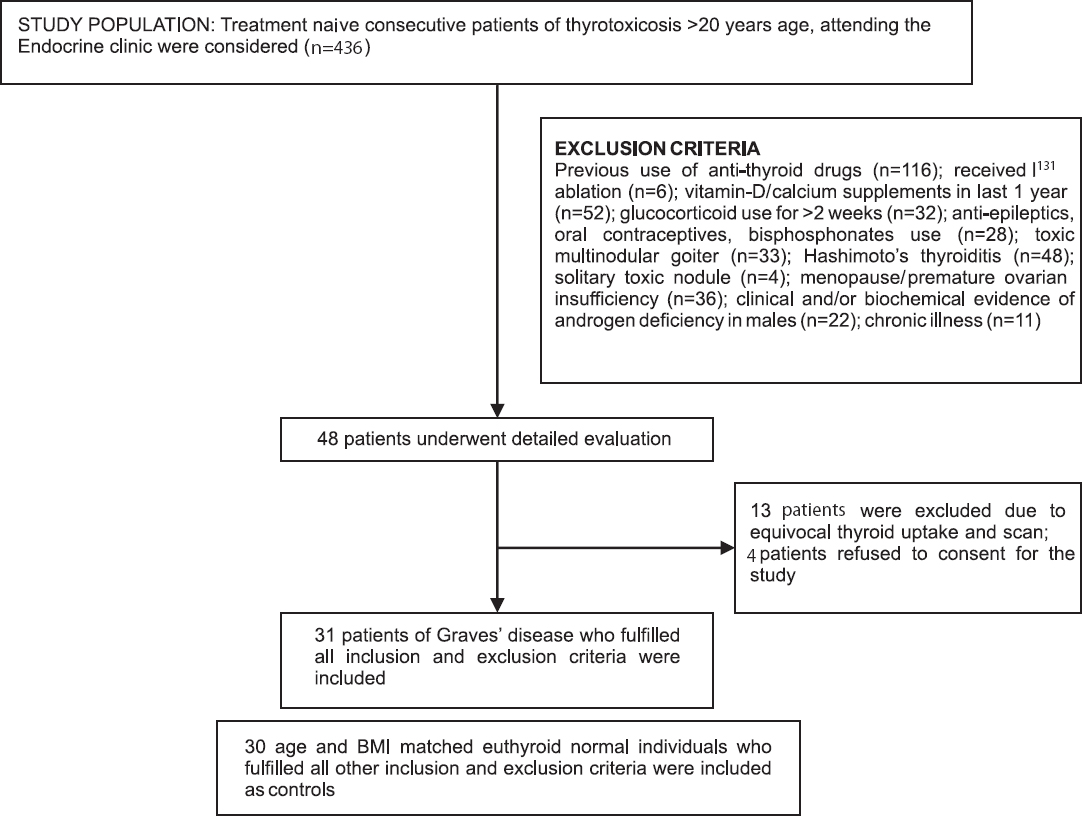

Treatment naive consecutive patients of thyrotoxicosis >20 yr age, attending the Endocrine clinic of the department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India, were considered. The duration of study was from August 2008 till December 2012. Patients with GD were included in the study. Graves’ disease was defined as those having clinical and biochemical evidence of hyperthyroidism along with increased as well as diffuse uniform uptake on I131 nuclear imaging13. Patients with previous history of fracture, history of anti-thyroid drug use (carbimazole, methimazole or propylthiouracil) any time in the past, steroid use for >2 wk any time in the past, on vitamin D or calcium supplementation in the last one year, anti-epileptic drugs, oral contraceptive pills or bisphosphonates use were also excluded. Women with other causes of thyrotoxicosis like toxic multinodular goiter, solitary toxic adenoma and Hashimoto's thyroiditis were also excluded. Women with menopause or premature ovarian insufficiency were excluded. Similarly men with clinical and/or biochemical evidence of androgen deficiency were also excluded. Also, patients with co-morbidities like chronic liver disease, renal disease, malignancy, uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes were excluded. Age and BMI matched clinically euthyroid family members of patients who gave consent and underwent assessment of thyroid function to confirm biochemical euthyroidism and who fulfilled all the exclusion criteria were considered as normal controls. Institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol. Thirty one patients with GD and 30 age and BMI matched normal controls were finally included in the study (Figure).

- Flowchart elaborating the study design.

Anthropometric indices: Duration of symptoms of thyrotoxicosis and smoking history were documented. All underwent detailed anthropometric assessment and clinical evaluation. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a Charder HM200PW wall-mounted stadiometer [calibrated using a 36” calibration rod (Perspective Enterprise, Portage, Michigan, USA)], and body weight was measured in light clothing to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic calibrated scale (Tanita, Japan, Model-HA521, Lot number-860525). Blood samples (5 ml) were collected, serum separated and stored at -70°C.

Biochemical tests: Serum T3, T4 and TSH levels were estimated using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Immulite-1000, Gwynedd, UK). Fasting blood glucose (FBG), 2 h post 75 g anhydrous glucose blood glucose (PGBG), liver function tests, calcium, phosphorus, and creatinine were estimated using clinical chemical analyzer (Daytona, serial number-58260536, Furuno Electric, Nishnomeya, Japan). 25-OHD was estimated using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Architect 25-OH Vitamin D assay, Abbott, USA; analytical sensitivity 4 ng/ml; range of 9.4 to 165.5 ng/ml).

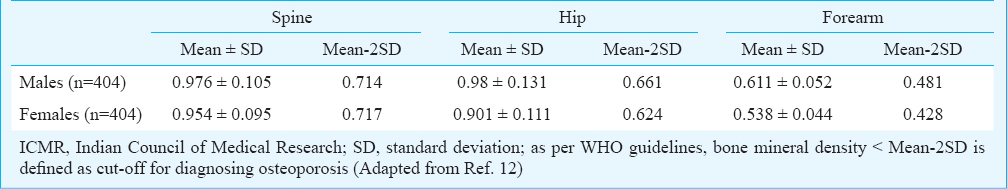

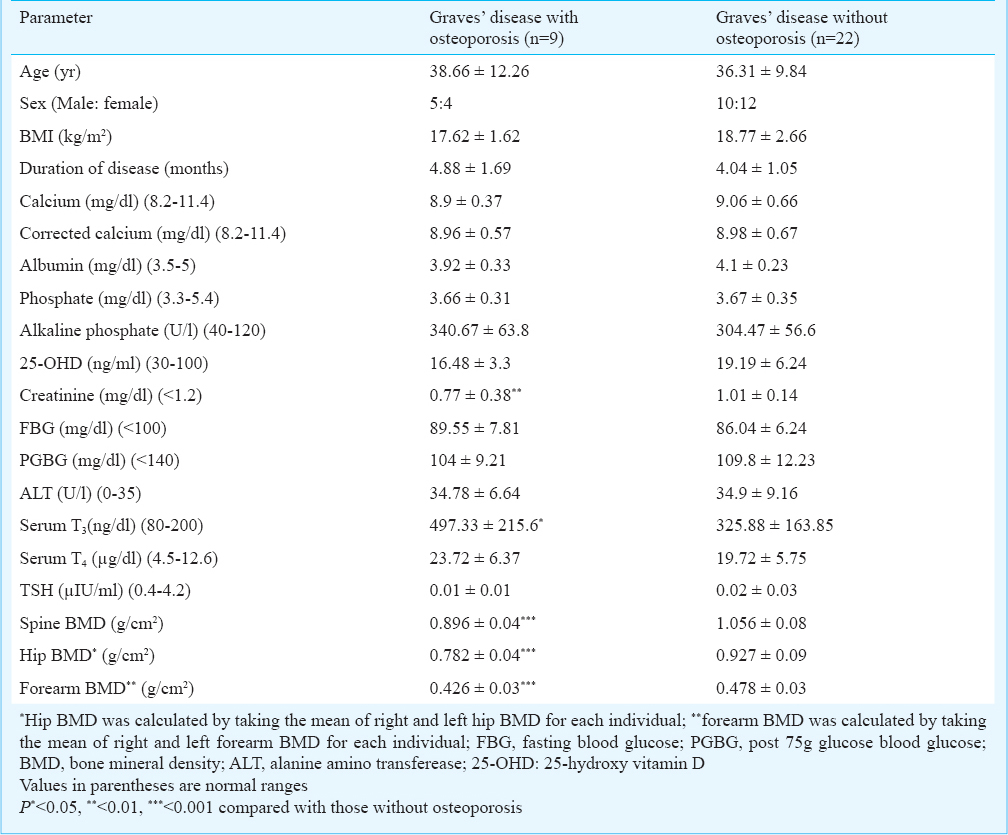

Bone mineral density assessment: DXA was done with a GE Lunar DPX NT densitometer (Model 8548; BX-1L, Madison, WI, USA) to determine bone mineral density (BMD) (g/cm2) at the lumbar spine (L1-L4), bilateral neck of femur and bilateral radius. Coefficient of variation for DXA ranged from 0.7 to 3.1 per cent. Normative data on peak bone mass by GE Lunar are available only for the Caucasian population. A population based study by the ICMR, involving 404 healthy Indian males and females each, between 20-29 yr age, from Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Lucknow has proposed Indian reference standards for peak bone density at hip, forearm and spine, in males and females as well as cut-off values for diagnosis for osteoporosis (Table I)12. These cut-off values were also used to diagnose osteoporosis in our patients besides the standard T-score calculation.

Statistical analysis: Student t test was used for analysis of continuous variables. Fisher's exact test was used for binary variable. χ2 test was used for categorical variables. One way ANOVA was used to study outcomes where three or more groups were present. Step-wise multiple linear regression models were used to estimate the regression coefficients for parameters showing significant bivariate association with BMD at different sites after adjusting for age, BMI and vitamin D. SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Inc., USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

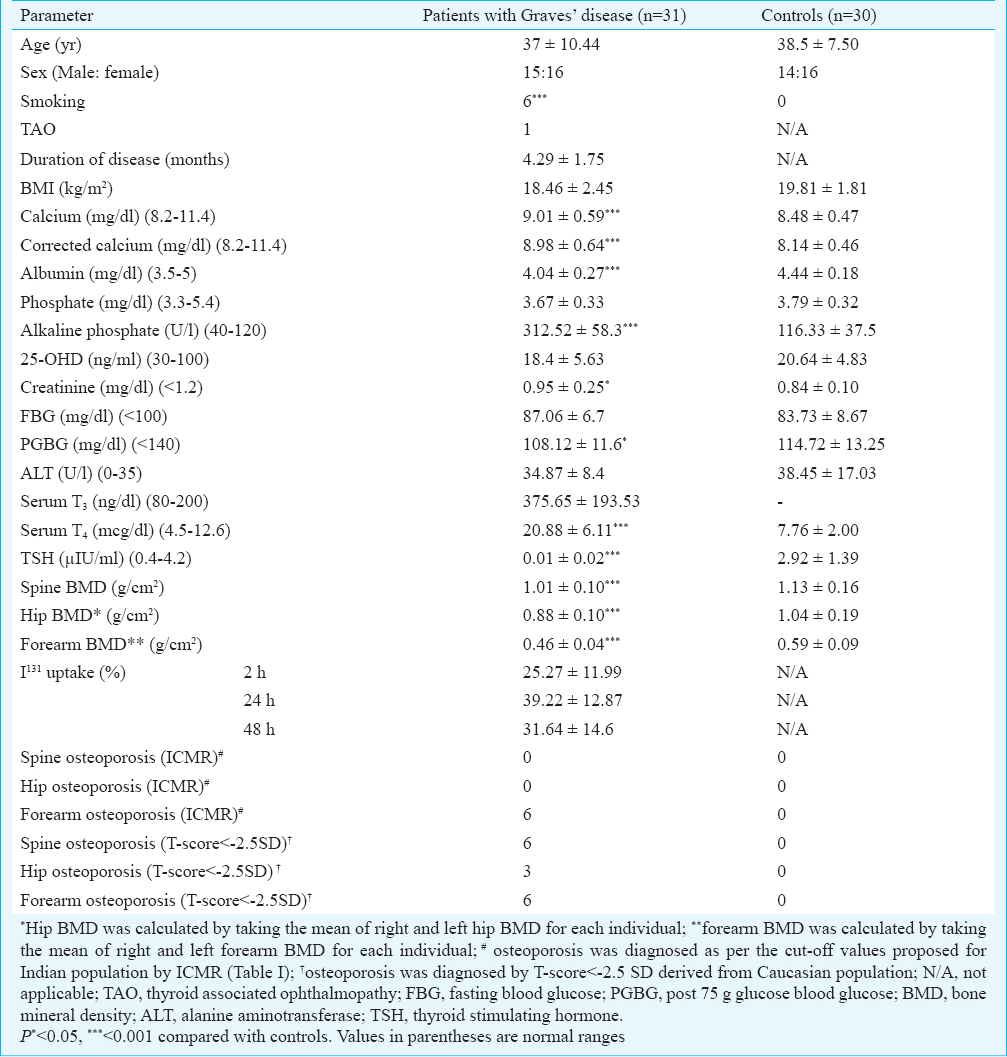

The mean age of patients with Graves’ disease was 37 ± 10.44 yr. Corrected serum calcium and alkaline phosphate (ALP) levels were significantly elevated in GD patients compared with controls (P<0.001) (Table II). Serum T4 was significantly elevated with concomitant suppressed TSH was observed in GD as expected (P<0.001). Patients with GD had a significantly lower BMD at spine, hip and forearm as compared with normal control individuals (P<0.001) (Table II). Osteoporosis was diagnosed in nine patients with GD using T-score derived from Caucasian population, which was significantly higher as compared to normal controls (9/31 vs. 0/30; P<0.05). One patient had osteoporosis at all three sites, two had osteoporosis at spine and forearm but not hip and two patients had osteoporosis at forearm and hip but not spine. Three patients had isolated osteoporosis at spine and one had isolated osteoporosis at forearm. Six patients were diagnosed to have osteoporosis using the ICMR criteria, all of them involving the forearm BMD. Spine and hip BMD was observed to be normal in GD patients using the ICMR criteria (Table II).

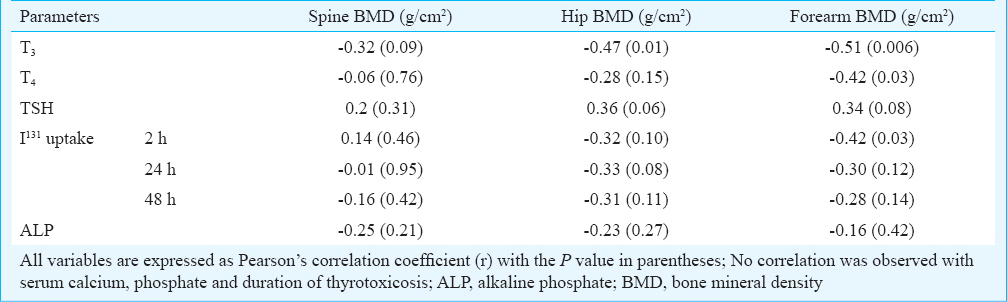

In patients with GD, serum T3 had an inverse correlation with BMD at spine (P=0.09), hip (P=0.01) and forearm (P=0.006), the strongest being with forearm BMD (Table III). Serum T4 had a significant inverse correlation with forearm BMD only (P=0.03). I131 uptake at 2 h had a significant inverse correlation with forearm BMD (P=0.03) (Table III). BMD at spine, hip or forearm did not have significant correlations with corrected serum calcium, phosphate or ALP. In normal controls, serum phosphate had a positive correlation with BMD at spine (r=0.54; P<0.001), hip (r=0.29; P=0.07) and forearm (r=0.31; P=0.054). Serum ALP had a negative correlation with BMD at spine (r=-0.42; P=0.007).

Comparison of clinical and biochemical parameters of GD patients with osteoporosis as compared with those without osteoporosis, revealed a significantly higher T3 (P<0.05) in patients with osteoporosis (Table IV).

For parameters showing bivariate association with BMD at different sites [T3, T4, TSH, corrected serum calcium, I131 uptake (2, 24 and 48 h), phosphate and alkaline phosphate], generalized linear models were constructed to determine their potential independent contributions to BMD after adjusting for age, BMI, and 25-OHD. In patients with GD, the best predictor of BMD at spine was T3 (β: -0.31; P=0.046) followed by I131 uptake at 48 h (β:-1.02; P=0.083), at hip was T3 (β: -0.36; P=0.071), and at forearm was T3 (β: -0.45; P=0.043) followed by phosphate (β: 0.37; P=0.059). Other studied parameters did not significantly predict BMD. In normal controls, serum phosphate and corrected calcium were the best predictors of BMD at spine (β: 0.430; P=0.023 and β: 0.211; P=0.051, respectively) and hip (β: 0.211; P=0.096 and β: 0.292, P=0.061, respectively). None of the studied parameters significantly predicted BMD at radius in normal controls.

Discussion

Our study showed that GD was associated with bone mineral loss both at cancellous and cortical bones, as evidenced by significantly lower BMD at spine, hip and forearm compared with normal controls. Osteoporosis was observed in 29 per cent (9/31) and 19.3 per cent (6/31) treatment naive newly diagnosed patients with GD, as per T-score and ICMR criteria, respectively. T-scores tended to overdiagnose osteoporosis among Indians compared to the ICMR criteria because the peak BMD at different sites in the ICMR study was significantly lower as compared with corresponding National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)-III and Holologic normative values12. With the ICMR criteria, osteoporosis was observed only at forearm, and not at hip or spine. Osteoporosis at spine or hip is not a major problem among young Indian treatment naive adults with Graves’ disease. Lack of BMD assessment at forearm may increase the chance of missing out diagnosing osteoporosis in GD. Hence assessment of BMD in GD should always include forearm along with spine and hip.

Low serum vitamin D may itself contribute to bone mineral loss. In our study, 25-OHD levels were lower in patients with Graves’ disease as compared with controls, but the difference was not significant. Low 25-OHD levels in patients with GD may be reflective of the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the general population or may be due decreased vitamin D synthesis following increased hyperpigmentation in GD, increased vitamin D metabolism or due to associated fat malabsorption impairing vitamin-D absorption1415. Jyotsna et al15 also reported low serum vitamin D in patients with Graves’ disease from north India. They also reported significantly lower BMD at spine, hip and forearm in patients with Graves’ disease compared with controls, which did not normalize even after two years of treatment highlighting the importance of vitamin D replacement in patients with Graves’ disease for improving bone health16.

Among the thyroid parameters, serum T3 had the strongest inverse correlation with BMD at spine, hip and femur, suggesting its important role in the development of osteoporosis. GD patients with osteoporosis had a significantly higher T3 levels as compared with those without, further highlighting the role of elevated T3 in osteoporosis development. Regression analysis confirmed that T3 was the best predictor of reduced BMD at spine, hip and forearm, with the strongest predictive value for forearm BMD. T3 and T4 have been demonstrated to stimulate osteoblastic activity in vitro and in organ cultures, which in turn increases releases of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kB ligand (RANK-L)1718. RANK-L, in association with increased inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNFα) in hyperthyroidism, causes increased osteoclast activation resulting in increased bone mineral loss181920. Thyroid hormones have a predominantly catabolic effect on a mature skeleton, with the osteoclast activity overwhelming the osteoblast activity, explaining low BMD in adult thyrotoxicosis20.

Our observations were in accordance with previous observations in large population studies involving normal euthyroid individuals. Van der Deure et al20 reported that serum free T4 and TSH had a significant inverse and positive correlation respectively with hip BMD in 1151 euthyroid individuals >55 yr age, with a much stronger association for free T4. Lower serum TSH in normal range correlated with lower spine and hip BMD in 959 post-menopausal women from Korea21. In a study of 1961 euthyroid individuals from Norway, individuals with serum TSH <2.5th percentile had a significantly lower forearm BMD and individuals with TSH >97.5th percentile had a significantly higher hip BMD22. A weak negative inverse correlation between free T4 and BMD was reported from 2957 euthyroid individuals from Taiwan23. However, similar correlations were not observed in normal controls in our study due to the small number of individuals studied.

Baseline I131 uptake was inversely associated with BMD in our study. Regression analysis revealed that I131 uptake at 48 h was an important predictor of spine BMD. Hence a high I131 uptake besides being helpful in diagnosing GD, may also be a predictor of increased bone mineral loss. Further studies are needed in a larger cohort to confirm this initial observation.

Serum ALP, a bone formation marker from osteoblasts, was significantly elevated in GD patients as compared with normal controls confirming the increased bone turnover observed in patients with hyperthyroidism12. The ICMR study showed that serum ALP was an important predictor of forearm BMD in normal individuals12. Although expected, no correlation was observed between ALP and thyroid hormones in this study (both being important predictors of BMD in thyrotoxicosis). El Hadidy et al2 also did not observe any correlation between bone formation/resorbtion markers and T3/T4. Variability in the duration of hyperthyroidism2, and differential tissue response may be the cause for this discordance between hyperthyroidism severity and degree of bone turnover. Serum phosphate was an important predictor of BMD at forearm in GD patients, and at spine and hip in normal control individuals, highlighting the important role of phosphate in bone metabolism. Serum phosphate has previously been documented to be an important predictor of BMD at spine and hip in ageing healthy men21. In the ICMR study also, significant positive correlation was observed between serum phosphate and BMD at forearm in normal young males12. Presence of adequate levels of phosphate in serum is a necessary prerequisite for bone apposition. Lack of study of bone turnover markers other than ALP is one of the limitations of this study, another being the cross-sectional nature.

To conclude it may be said that osteoporosis at hip or spine is not a major problem among young adults with GD when the ICMR criterion is used for diagnosis. Standard criterion developed from Caucasians tends to overdiagnose osteoporosis. Osteoporosis in young adults with GD more commonly involves the forearm. Elevation of thyroid hormones (especially T3) and serum phosphate are important predictors of BMD in GD. Baseline I131 uptake may have some role in predicting BMD in GD, needing further evaluation in future studies.

References

- Thyrotoxicosis. In: Williams textbook of endocrinology (12th ed). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011. p. :365-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of severity, duration, and etiology of hyperthyroidism on bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in men. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2011;11:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid hormones, and bone loss. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;7:47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperthyroidism, bone mineral, and fracture risk - a meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2003;13:585-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of thyroid hormone on skeletal integrity. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:750-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone mass in females with different thyroid disorders: influence of menopausal status. Bone Mineral. 1993;21:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone loss in hyperthyroid patients and in former hyperthyroid patients controlled on medical therapy: influence of etiology and menopause. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47:279-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Official positions of the international society for clinical densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:75-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Medical Research. In: Population based reference standards of peak bone mineral density of Indian males and females-an ICMR multi-center task force study. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2010. p. :1-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypovitaminosis D and bone mineral metabolism and bone density in hyperthyroidism. J Clin Densitom. 2010;13:462-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and significance of steatorrhea in patients with active Graves’ disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1122-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone mineral density in patients of Graves disease pre- & post- treatment in a predominantly vitamin D deficient population. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:36-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tri-iodothyronine stimulates rat osteoclastic bone resorption by an indirect effect. J Endocrinol. 1992;133:327-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Osteoblasts mediate thyroid hormone stimulation of osteoclastic bone resorption. Endocrinology. 1994;134:169-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid hormone stimulates basal and interleukin(IL)-1-induced IL-6 production in human bone marrow stromal cells: a possible mediator of thyroidhormone-induced bone loss. J Endocrinol. 1999;160:97-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid status during skeletal development determines adult bone structure and mineralization. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1893-904.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of serum TSH and FT4 levels and the TSHR-Asp727Glu polymorphism on bone: the Rotterdam Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;68:175-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Low normal TSH levels are associated with low bone mineral density in healthy postmenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol. 2006;64:86-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between serum TSH and bone mineral density in men and postmenopausal women: the Tromsø study. Thyroid. 2008;18:1147-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between thyroid function and bone mineral density in euthyroid healthy subjects in Taiwan. Endocr Res. 2011;36:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]