Translate this page into:

Micronutrient status of Indian population

For correspondence: Dr G.S. Toteja, Centre for Promotion of Nutrition Research and Training with Special Focus on North East, Tribal and Inaccessible Population, Division of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research (Campus II), Tuberculosis Association of India Building, 3 Red Cross Road, New Delhi 110 001, India e-mail: gstoteja@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Micronutrients play an important role in the proper growth and development of the human body and its deficiency affects the health contributing to low productivity and vicious cycle of malnutrition, underdevelopment as well as poverty. Micronutrient deficiency is a public health problem affecting more than one-fourth of the global population. Several programmes have been launched over the years in India to improve nutrition and health status of the population; however, a large portion of the population is still affected by micronutrient deficiency. Anaemia, the most common form of micronutrient deficiency affects almost 50 to 60 per cent preschool children and women, while vitamin A deficiency and iodine-deficiency disorders (IDD) have improved over the years. This review focuses on the current scenario of micronutrient (anaemia, vitamin A, iodine, vitamin B12, folate, ferritin, zinc, copper and vitamin C) status in the country covering national surveys as well as recent studies carried out.

Keywords

Anaemia

ferritin

folate

iodine

vitamin A

vitamin B12

Introduction

India has made tremendous progress in all fronts since independence including food production. Several programmes or schemes such as Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme, Mid-Day Meal Programme, National Iron Plus Initiative (NIPI), National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme (NIDDCP) and National Prophylaxis Programme against Nutritional Blindness due to Vitamin A Deficiency have also been launched over the years to improve the nutrition and health status of the population. However, still a large portion of the population suffers from malnutrition. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization report on State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World1, it is estimated that 190.7 million (14.5%) people were undernourished in India during 2014-2016.

Micronutrients though required in small amounts, are essential for proper growth and development of the human body2. Micronutrient deficiencies also referred to as ‘Hidden Hunger’ affects the health, learning ability as well as productivity owing to high rates of illness and disability contributing to vicious cycle of malnutrition, underdevelopment and poverty. It is estimated that around two billion people in the world are deficient in one or more micronutrients3. Micronutrient deficiencies (such as iodine, iron and vitamin A deficiency) not only affect the health but are also projected to cost around 0.8-2.5 per cent of the gross domestic product4. In India, around 0.5 per cent of total deaths in 2016 were contributed by nutritional deficiencies5.

National surveys such as National Family Health Survey (NFHS), National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB), Annual Health Survey (AHS) and District Level Household Survey (DLHS) have been carried out to assess the health and nutrition status of the population in the country. The national surveys carried out have mainly focused on nutritional status based on anthropometric measurements, dietary intake and anaemia though independent surveys have been carried out to assess micronutrient deficiencies in the country. This review focuses on the current scenario of micronutrient status in the country covering national surveys as well as recent studies carried out. Studies on dietary intake have not been covered.

Iron, vitamin B12, folate and ferritin deficiency

Anaemia is a major public health problem in the country as well as globally affecting nearly a third of the global population6. The National Nutritional Anaemia Prophylaxis Programme was launched in 1970 to prevent nutritional anaemia among children, expectant and nursing mothers as well as acceptors of family planning. The programme was later renamed in 1991 as National Nutritional Anaemia Control Programme targeting women in reproductive age group, especially pregnant and lactating women and preschool children7. The three strategies of the programme were promotion of regular consumption of foods rich in iron, provisions of iron and folate supplements in the form of tablets (folifer tablets) to the ‘high-risk’ groups and identification and treatment of severely anaemic cases8. In 2013, the Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation Programme was launched to reduce the prevalence and severity of nutritional anaemia among adolescents. Under this Programme, adolescents studying in class VI to XII from either government or government-aided or municipal schools as well as adolescent girls who are not in school are covered9. Subsequently, NIPI was launched in 2013 to prevent and control anaemia covering almost the entire age group, from infants six months onwards to women of reproductive age, providing weekly iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation and deworming tablets administered twice a year, while daily dose of IFA tablet is being provided for 100 days during pregnancy as well as 100 days after delivery for lactating women10. However, more than half of the population still suffers from anaemia. As per the Global Burden of Disease Study 20165, iron-deficiency anaemia is among the top 10 causes of disability-adjusted life years for women. The latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS4) carried out by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare reported the prevalence of anaemia as 58.6, 53.1, 50.4 and 22.7 per cent, respectively, among children aged 6-59 months, women aged 15-49 yr, pregnant women aged 15-49 yr and men aged 15-49 yr11.

Besides national surveys, various studies carried out in the country have also reported high burden of anaemia. A Task Force Study carried out by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, across 16 districts of 11 States among 11,260 pregnant women (n=6923) and adolescent girls (n=4337) also reported the prevalence of anaemia as 84.9 and 90.1 per cent, respectively12. The NNMB (ICMR) survey carried out in eight States also reported anaemia of around 67 to 78 per cent among preschool children, adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women residing in the rural areas13. A study carried out among a cohort of pregnant women (n=72,750) residing in rural Maharashtra reported the prevalence of anaemia as 91 per cent14. A study carried out in rural Telangana among women aged 15-35 yr (n=979) reported lower prevalence of anaemia (28.4%) whereas prevalence of other micronutrient deficiencies such as ferritin (46.3%), folate (56.8%) and vitamin B12 (44.4%) was reported to be around 50 per cent15.

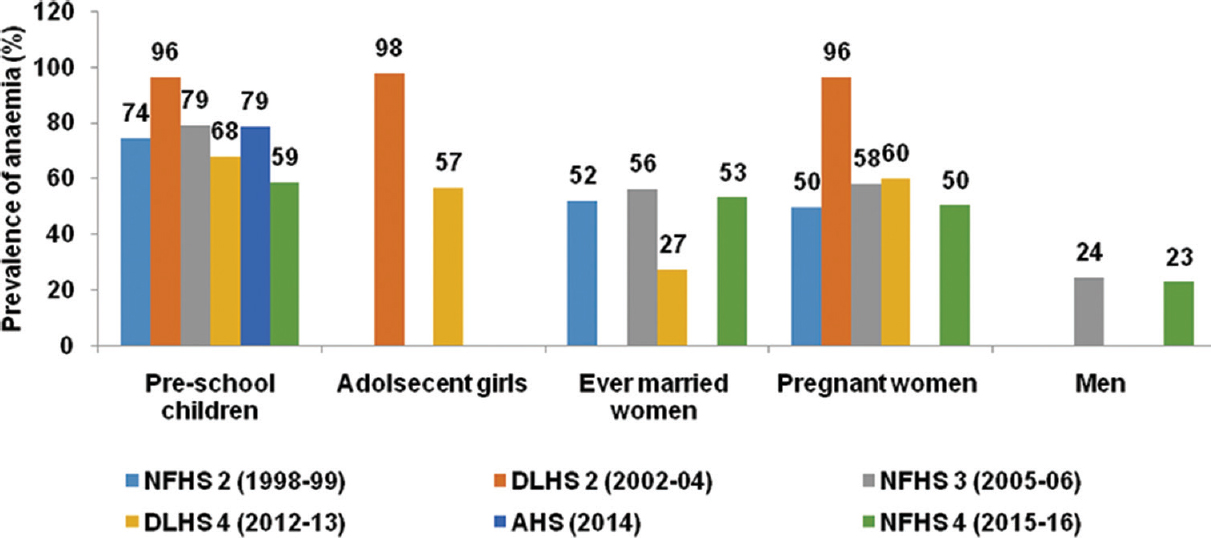

Various initiatives taken by the Government of India have led to reduction in the prevalence of anaemia in the country (Figure). The prevalence of anaemia among preschool children has reduced in the past 16 yr by almost 16 per cent from 74.3 per cent during 1998-199916 to 58.5 per cent during 2015-201611. Similarly, DLHS surveys1819 have also shown reduction in anaemia among adolescent girls aged 10-19 yr by 41.3 per cent. A slight decrease (1.6%) in the prevalence of anaemia was also observed among men. Among ever married and pregnant women, not much improvement was observed compared to findings of NFHS-216; however, compared to findings of other surveys carried out after 2000, a reduction of 3-7 per cent was observed.

- Trend analysis of the prevalence of anaemia. Source: Refs 11, 16-20.

Nutritional anaemia can be caused due to deficiencies of micronutrients such as iron, folic acid and vitamin B12, with iron deficiency being the most common cause of anaemia. There is no nationwide data on status of these micronutrients; however, recent studies have highlighted that deficiencies still exist in the Indian population. With respect to vitamin B12 deficiency, studies have indicated deficiency as high as 70-100 per cent (Table I). This may also be because about 29 per cent of the Indian population is vegetarian39. The prevalence of folate deficiency is not high as compared to vitamin B12 deficiency; however, studies carried out in New Delhi and Maharashtra among preschool children and adolescents have indicated deficiency of around 40 to 60 per cent (Table II). Studies have reported the prevalence of low ferritin in almost 60 to 70 per cent of the population (Table III).

| Study | Study area | Study design | Cut-off used for serum vitamin B12 | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chakraborty et al, 201821 | NCR Region and Haryana | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <148 pmol/l | 32.4 Rural: 43.9; Urban: 30.1 |

| School-going adolescents (n=2403) (11-17 yr) | ||||

| Gonmei et al, 201822 | New Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <203 pg/ml | 36.4 |

| Elderly aged 60 and above (n=77) residing in slums | ||||

| Gupta et al, 201723 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <203 pg/ml | 7.4 |

| Schoolchildren (n=215) aged 6-18 yr | ||||

| Verma 201724 | Maharashtra | School-based cross-sectional study. | <200 pg/ml | 72.7 |

| Adolescents (n=373) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Mittal et al, 201725 | New Delhi | Hospital-based cross-sectional study. | <200 pg/ml | Infants-57.0 Mothers-46.0 |

| Term exclusively breastfed infants (n=100) aged 1-6 months | ||||

| Goyal et al, 201726 | Rajasthan | Hospital-based descriptive study. | <100 pg/ml | 37.5 |

| SAM children (n=80) | ||||

| Surana et al, 201727 | Gujarat | Hospital-based cross-sectional study. | <160 pg/ml | 49.8 |

| Adolescents (n=211) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Gonmei et al, 201728 | New Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <203 pg/ml | 38.0 |

| Women (n=60) aged 60 and above residing in slums | ||||

| Sivaprasad et al, 201629 | Telangana | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <203 pg/ml | 35.0 |

| Adults (n=630) aged 21-85 yr | ||||

| Garima et al, 201630 | - | Pregnant anaemic women (n=257) | <200 pg/ml | 67.0 |

| Gupta Bansal et al, 201531 | New Delhi | Community-based study. | <203 pg/ml | Anaemia-58.7, 63.3 among anaemic adolescents |

| Adolescents (n=794) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Parmar et al, 201532 | Gujarat | Hospital-based cross-sectional study. | <200 pg/ml | 44.6 <30 yr - 31.5 30 to 60 yr - 39.3 >60 yr - 62.5 |

| Individuals (n=2660) aged 0-96 yr | ||||

| Kapil et al, 201533 | NCT Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <203 pg/ml | 38.4 |

| Children (n=470) aged 12-59 months | ||||

| Chahal et al, 201434 | Himachal Pradesh | Observational study. | <200 pg/ml | 43.6 |

| Adults (n=153) aged 18-62 yr | ||||

| Kapil and Bhadoria 201435 | NCT Delhi | School-based cross-sectional study. | <200 pg/ml | 73.5 |

| Adolescents (n=347) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Bhardwaj et al, 201336 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <200 pg/ml | 100.0 |

| Adolescents (n=885) aged 11-19 yr (n=200 for blood sample) | ||||

| Shobha et al, 201137 | Karnataka | Elderly (n=175) aged 60 and above | - | 16.0 |

| Menon et al, 201138 | Maharashtra | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <148 pmol/l | 34.0 |

| Tribal and rural women of reproductive age (n=109) |

SAM, severe acute malnutrition; NCT, National Capital Territory

| Study | Study area | Study design | Cut-off used for serum folic acid | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhide and Kar 201840 | Maharashtra | Hospital-based study. | <3 ng/ml | 24.0 |

| Women (n=584) in early pregnancy | ||||

| Verma 201724 | Maharashtra | School-based cross-sectional study. | <3 ng/ml | 40.2 |

| Adolescents (n=373) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Goyal et al, 201726 | Rajasthan | Hospital-based descriptive study. | <3 ng/ml | 8.8 |

| SAM children (n=80) | ||||

| Gonmei et al, 201728 | New Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <4 pg/ml | 12.0 |

| Women (n=60) aged 60 and above residing in slums | ||||

| Gupta et al, 201723 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <4 ng/ml | 1.5 |

| Schoolchildren (n=215) aged 6-18 yr | ||||

| Sivaprasad et al, 201629 | Telangana | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <3 ng/ml | 12.0 |

| Adults (n=630) aged 21-85 yr | ||||

| Gupta Bansal et al, 201531 | New Delhi | Community-based study. | <4 ng/ml | Anaemia - 58.7 5 among anaemic adolescents |

| Adolescents (n=794) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Kapil et al, 201533 | NCT Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <4 ng/ml | 63.2 |

| Children (n=470) aged 12-59 months | ||||

| Kapil and Bhadoria 201435 | NCT Delhi | School-based cross-sectional study. | <3 ng/ml | 39.8 |

| Adolescents (n=347) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Bhardwaj et al, 201336 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <2.7 ng/ml | 0 |

| Adolescents (n=885) aged 11-19 yr (n=200 for blood sample) | ||||

| Menon et al, 201138 | Maharashtra | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <6.8 nmol/l | 2.0 |

| Tribal and rural women (n=109) of reproductive age |

| Study | Study area | Study design | Cut-off used for serum ferritin | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gupta Bansal et al, 201531 | New Delhi | Community-based study. | <15 ng/ml | Anaemia - 58.7 41.1 among anaemic adolescents |

| Adolescents (n=794) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Bains et al, 201541 | Punjab | Community-based study. | <10 µg/l | 71.8 |

| Children (n=312) aged six months to 5 yr | ||||

| Kapil and Bhadoria 201435 | NCT Delhi | School-based cross-sectional study | <12 ng/ml | 59.7 |

| Adolescents (n=347) aged 11-18 yr | ||||

| Bhardwaj et al, 201336 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study. | <12 ng/ml | 15.0 |

| Adolescents (n=885) aged 11-19 yr (n=200 for blood sample) |

Vitamin A deficiency

The Government of India launched the National Prophylaxis Programme against Nutritional Blindness due to vitamin A deficiency in 1970 targeting children aged 1-6 yr with the specific aim of preventing nutritional blindness due to keratomalacia. The programme was modified in 1994, under the National Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Programme where the target group was restricted to 9-36 months children. The age of the target group was later modified as 6 to 59 months in 200642. As per NFHS-411, the percentage of children aged 9-59 months who received a vitamin A dose in the past six months has increased from 16.5 (2005-2006) to 60.2 per cent (2015-2016).

The multicentre study carried out by ICMR in 16 districts covering 1.64 lakh preschool children revealed the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency (Bitot's spots) as 0.83 per cent43. Another survey carried out by NNMB (ICMR) during 2002-2005 in eight States (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal) reported similar prevalence of Bitot's spots (0.8%) among 71,591 rural preschool children44. Repeat surveys carried out by NNMB in seven States of the country covering rural preschool children have indicated reduction in the prevalence of vitamin A deficiency (Bitot's spots) from 0.7 (1996-1997) to 0.2 per cent (2011-2012)45. The Central India Children Eye Study carried out among 11829 schoolchildren of government schools in Nagpur, Maharashtra, reported the prevalence of Bitot's spots as 0.1 per cent46. The prevalence of Bitot's spots was also reported as 0.19 per cent among children 0-5 yr in Meghalaya47.

The prevalence of subclinical vitamin A deficiency (serum retinol <20 μg/dl) among preschool children was reported to be around 62 per cent as revealed by NNMB survey carried out during 2002-200548. A recent carried study carried out in Phek District of Nagaland covering 661 preschool children aged less than five years reported the prevalence of subclinical vitamin A deficiency as 32.6 per cent49. The prevalence of subclinical vitamin A deficiency (serum retinol <20 μg/dl) was reported as four per cent among tribal rural women of reproductive age in Central India38.

Iodine deficiency

The National Goitre Control Programme was launched by the Government of India in 1962 after successful demonstration of salt iodisation to control iodine-deficiency disorders (IDD) in Kangra Valley of Himachal Pradesh. The programme was later renamed as NIDDCP in 1992 focusing on universal salt iodisation. At present, sale of non-iodised salt for direct human consumption is banned under the Food Safety and Standards Act, 200650.

The initiatives taken by the Government has resulted in an increase in percentage of households (NFHS-2) using iodised salt, i.e., from 71.6 per cent during 1998-199916 to 93.1 per cent during 2015-201611. The National Iodine and Salt Intake Survey (2014-2015) also reported that 78 per cent of the households were consuming adequate iodised salt51.

Salt iodine content at the production and packaging site, wholesale and retail levels and in households; urinary iodine levels; thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels and change in goitre prevalence are indicators for monitoring and evaluating IDD control programmes52. In India, of the 414 districts surveyed so far up to the year 2015-2016, 337 districts were found to be endemic for IDD (total goitre rate >5%)53. However, NNMB survey carried out during 2002-2005 in eight States, i.e., Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, reported total goitre rate of 3.9 per cent among schoolchildren44. Some of the recent surveys carried out in the country have reported total goitre rate of more than 5 per cent (Table IV). Further, median urinary iodine concentration, an indicator of current intake indicated adequate iodine intake among schoolchildren aged 6 yr and above (>100 μg/l) and non-pregnant women. A study carried out in Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, after 60 yr of salt iodisation also reported adequate iodine intake among schoolchildren aged 6-12 yr as indicated by median urinary iodine concentration of 200 μg/l, while total goitre rate was still more than 15 per cent66. Around 60 to 80 per cent neonates in Himachal Pradesh were also reported to be deficient in iodine (TSH >5 mUI/l)7677.

| Study | Study area | Study design | Total goitre rate (%) | Median urinary iodine concentration (µg/l) | Percentage of iodised salt consumption (≥15 ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | |||||

| Amrutha et al, 201454 | Tamil Nadu | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=2800) | - | Male - 114.7; female - 121.8 (range: 39.9-226.5) | - |

| Schoolchildren | |||||

| Shetty et al, 201855 | Karnataka | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=2703) (Goitre); 270 (UIC); 543 (salt) | 9.3 | 202.12 | 69.8 |

| Bali et al, 201856 | Madhya Pradesh | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=2700) (Goitre); 270 (UIC); 540 (salt) | 2.08 | 175 | 72.4 |

| Sareen et al, 201657 | Uttarakhand | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=6143) | Udham Singh Nagar-13.2 | Udham Singh Nagar - 150 | - |

| Nainital-15.9 | Nainital - 125 | ||||

| Pauri Garhwal-16.8 | Pauri Garhwal - 115 | ||||

| Gupta et al, 201658 | Jammu | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=3955) (Goitre); 400 (salt) | Rajouri- 18.87 | - | 100 |

| Poonch-19.70 | |||||

| Manjunath et al, 201559 | Karnataka | Community-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=832) | 21.9 | 150 | - |

| Ahmed et al, 201460 | Karnataka | Community-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=10082) | 19.01 | - | 40.1 |

| Kapil et al, 201561 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=5748) | Kangra-15.8 | Kangra - 200 | - |

| Kullu- 23.4 | Kullu - 175 | ||||

| Solan-15.4 | Solan - 62.5 | ||||

| Kapil et al, 201462 | Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=1807) (TGR); 587 (UIC); 660 (salt) | 13.2 | 150 | 46.7 |

| Kapil et al, 201463 | Pauri, Uttarakhand | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=2067) (TGR); 580 (UIC); 562 (salt) | 16.8 | 115 | 40.4 |

| Sridhar and Kamala 201464 | Karnataka | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-15 yr) (n=1600) (goitre); 400 (salt) | 0.125 | 179 | 90.7 |

| Biswas et al, 201465 | Darjeeling, West Bengal | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 8-10 yr) (n=2400) | 8.67 | 156 | 92.6 |

| Kapil et al, 201366 | Kangra, Himachal Pradesh | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=1864) (TGR); 463 (UIC); 327 (salt) | 15.8 | 200 | 82.3 |

| Contd… | |||||

| Kapil et al, 201467 | Nainital District, Uttarakhand | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=2269) (TGR); 611 (UIC); 642 (salt) | 15.9 | 125 | 57.5 |

| Kapil et al, 201368 | NCT Delhi | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-11 yr) (n=1393) | - | 200 | 87.0 |

| Chaudhary et al, 201369 | Haryana | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6-12 yr) (n=2700) | 12.6 | >100 | 88.0 |

| Zama et al, 201370 | Karnataka | School-based cross-sectional study (aged 6 to 12 yr) (n=3757) | 7.74 | - | - |

| Adolescent girls | |||||

| Sareen et al, 201657 | Uttarakhand | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=5430) | Udham Singh Nagar - 6.8 | Udham Singh Nagar - 250 | - |

| Nainital - 8.2 | Nainital - 200 | ||||

| Pauri Garhwal - 5.6 | Pauri Garhwal - 183 | ||||

| Pregnant women | |||||

| Kant et al, 201771 | Haryana | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=1031) | - | 260 (range: 199-333) | 90.9 |

| Rao et al, 201872 | New Delhi | Community-based cross-sectional study | - | 147.5 | 70.6 |

| Sareen et al, 201657 | Uttarakhand | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=1727) | Udham Singh Nagar - 16.1 | Udham Singh Nagar - 124 | |

| Nainital - 20.2 | Nainital - 117.5 | ||||

| Pauri Garhwal - 24.9 | Pauri Garhwal - 110 | ||||

| Kapil et al, 201573 | Uttarakhand | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=1727) (TGR); 1040 (UIC) and 1494 (Salt) | Pauri-24.9 | Pauri – 110 | Pauri - 57.9 |

| Nainital - 67.0 | |||||

| Nainital-20.2 | Nainital - 117.5 | ||||

| Udham Singh Nagar - 50.3 | |||||

| Udham Singh Nagar-16.1 | Udham Singh Nagar - 124 | ||||

| Kapil et al, 201474 | Himachal Pradesh | Community-based cross-sectional study (n=1711) (TGR); 1118 (UIC) and 1283 (Salt) | Kangra-42.2 | Kangra - 200 | Kangra - 68.3 |

| Kullu - 42.0 | Kullu - 149 | ||||

| Kullu - 60.3 | |||||

| Solan - 48.6 | |||||

| Solan-19.9 | Solan - 130 | ||||

| Joshi et al, 201475 | Vadodara, Gujarat | Hospital-based cross-sectional study (n=256) (gestational age, 15 wk) | - | 297.14 | - |

TGR, total goitre rate; UIC, urinary iodine concentration

Insufficient iodine intake among pregnant women has been reported with median urinary iodine concentration of <150 μg/l5771727374. The ongoing Task Force Study on IDD by ICMR at 10 districts of the country would provide a better picture on the current status of iodine status among pregnant women.

Other micronutrient deficiencies

Limited studies have been carried out in the country to assess status of other micronutrients. Studies carried out to assess copper levels have reported deficiency of around 29 to 34 per cent among pregnant women and adult tribal population7879. Available literature on zinc levels has indicated high prevalence of zinc deficiency among children aged 6-60 months (43.8%), adolescents (49.4%) and pregnant women (64.6%)808182. Similarly, the prevalence of zinc deficiency has been reported to be around 52 to 58 per cent among tribal non-pregnant women in Central India38. While studies carried out among pregnant women in Assam (12%) and children aged six months to five years in Punjab (18%) reported lower prevalence of zinc deficiency7883, a recently published study84 projected that by 2050, the prevalence of zinc deficiency would increase by 2.9 per cent due to anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Anthropogenic CO2 emission disrupts the global climate system affecting food production and altering the nutrient profile of staple food crops and is likely to increase nutrient deficiencies.

Only few studies have also been carried out to assess vitamin C deficiency with plasma vitamin C as an indicator. The India age-related eye disease study carried out among the elderly aged 60 and above in north and south India reported the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency as 73.9 and 45.7 per cent, respectively85. Another study carried out among adolescent girls (n=775), residing in slums of New Delhi reported the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency as only 6.3 per cent86.

Conclusion

Micronutrient deficiency is a major health problem in the country, with anaemia affecting almost 50 to 60 per cent of the population while vitamin A deficiency and IDD have improved over the years. With recent initiatives of the government and strengthening existing health and agriculture systems, micronutrient status of the population is expected to improve in the coming years.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. 2017. Building resilience for peace and food security. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-I7695e.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Micronutrients. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/micronutrients/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- Combating micronutrient deficiencies: Food-based approaches. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and CAB International; 2011.

- India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators. Nations within a nation: Variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990-2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;390:2437-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micronutrient profile of Indian population. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004.

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. Policy on control of nutritional anaemia. Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India 1991

- [Google Scholar]

- National Health Mission. 2015. Weekly Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFS). New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; Available from: http://www.nhm.gov.in/nrhm-components/rmnch-a/adolescenthealth-rksk/weekly-iron-folic-acid-supplementation-wifs/background.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Implementation of national iron plus initiative for child health: Challenges ahead. Indian J Public Health. 2015;59:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015-16. Mumbai: IIPS; Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Reports/India.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women and adolescent girls in 16 districts of India. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:311-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. NNMB Technical report No: 22. 2003. Prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; Available from: http://www.nnmbindia.org/NNMB%20MND%20REPORT%202004-web.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal anemia and underweight as determinants of pregnancy outcomes: Cohort study in Eastern rural Maharashtra, India. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021623.

- [Google Scholar]

- Folate, vitamin B12, ferritin and haemoglobin levels among women of childbearing age from a rural district in South India. BMC Nutr. 2017;3:50.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. 2000. National family health survey (NFHS-2) 1998-99. Mumbai: IIPS; Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND2/FRIND2.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06. Mumbai: IIPS; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/frind3/frind3-vol1andvol2.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. 2006. District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-2) 2002-04. Nutritional status of children and prevalence of anaemia among women, adolescent girls and pregnant women. Mumbai: IIPS; Available from: http://rchiips.org/pdf/rch2/National_Nutrition_Report_RCH-II.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences. In: District Level Household & Facility survey (DLHS-3). Mumbai: IIPS; 2007-08.

- [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Clinical, Anthropometric and Biochemical (CAB) 2014. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/hh-series/cab.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Vitamin B12 deficiency in healthy Indian school-going adolescents from rural and urban localities and its relationship with various anthropometric indices: A cross-sectional study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;4:513-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaemia and Vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11:402-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Vitamin B12 and folate deficiency in school children residing at high altitude regions in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2017;84:289-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of Vitamin B12 and folate deficiency amongst adolescents. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2017;4:1755-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perturbing status of Vitamin B12 in Indian infants and their mothers. Food Nutr Bull. 2017;38:209-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cobalamin and folate status in malnourished children. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4:1480-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vitamin B12 status among anaemic adolescents. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:1780-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemoglobin, folate and Vitamin B12 status of economically deprived elderly women. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;8:133-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of Vitamin B12 and folate among the urban adult population in South India. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;68:94-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of Vitamin B12 deficiency in anemia in pregnancy. Int J Adv Sci Eng Technol. 2016;4:116-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Deficiencies of serum ferritin and Vitamin B12, but not folate, are common in adolescent girls residing in a slum in Delhi. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2015;85:14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cobalamin and folate deficiencies among children in the age group of 12-59 months in India. Biomed J. 2015;38:162-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- How common is Vitamin B12 deficiency - A report on deficiency among healthy adults from a medical college in rural area of North-West India. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2014;4:241-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of folate, ferritin and cobalamin deficiencies amongst adolescent in India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3:247-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid assessment for coexistence of Vitamin B12 and iron deficiency anemia among adolescent males and females in Northern Himalayan state of India. Anemia. 2013;2013:959605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vitamin B12 deficiency & levels of metabolites in an apparently normal urban South Indian elderly population. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:432-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concurrent micronutrient deficiencies are prevalent in nonpregnant rural and tribal women from central India. Nutrition. 2011;27:496-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sample Registration System Baseline Survey 2014. Census of India. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/BASELINE%20TABLES08082016.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of folate deficiency among urban Indian women in the periconception period. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018 doi:10.1038/s41430-018-0255-2

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron and zinc status of 6-month to 5-year-old children from low-income rural families of Punjab, India. Food Nutr Bull. 2015;36:254-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Massive dose Vitamin A programme in India - need for a targeted approach. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:411-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vitamin A deficiency disorders in 16 districts of India. Indian J Pediatr. 2002;69:603-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of micronutrient deficiencies among rural children of eight states in India. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62:231-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. In: Technical report No. 26. Diet and nutritional status of rural population, prevalence of hypertension & diabetes among adults and infant & young child feeding practices: Report of third repeat survey. Hyderabad: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vitamin A deficiency in schoolchildren in urban central India: The central India children eye study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:1095-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of Vitamin A deficiency among children in Meghalaya and the underlying social factors. Indian J Child Health. 2015;2:59-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. In: Technical report No: 23. Prevalence of Vitamin A deficiency among preschool children in rural areas. Hyderabad: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mother and child nutrition among the chakhesang tribe in the state of Nagaland, North-East india. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13((Suppl 3)):e12558.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evolution of iodine deficiency disorders control program in India: A Journey of 5,000 years. Indian J Public Health. 2013;57:126-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- IDD Newsletter. 2015. Across India, women are iodine sufficient. India. Available from: http://www.ign.org/cm_data/IDD_nov15_india.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2001. Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination; a guide for programme managers. (2nd ed). Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/61278

- [Google Scholar]

- National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme (NIDDCP) Available from: http://www.nhm.gov.in/nrhmcomponents/national-disease-control-programmes-ndcps/iodinedeficiency-disorders.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Micronutrient malnutrition profile of infants in South India. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:54-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Goiter prevalence and interrelated components from coastal Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr 2018 doi:10-1007/s12098-018-2757-2

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine deficiency and toxicity among school children in Damoh district, Madhya Pradesh, India. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:579-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine nutritional status in Uttarakhand state, India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20:171-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Goiter prevalence in school-going children: A cross-sectional study in two border districts of sub-Himalayan Jammu and Kashmir. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:825-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and factors associated with goitre among 6-12-year-old children in a rural area of Karnataka in South India. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;169:22-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine deficiency in children: A comparative study in two districts of South-interior Karnataka, India. J Family Community Med. 2014;21:48-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine nutritional status in Himachal Pradesh state, India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:602-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine deficiency disorder in district Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand state India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:419-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine deficiency status amongst school children in Pauri, Uttarakhand. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:569-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine status and prevalence of goitre in school going children in rural area. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:PC15-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Goiter prevalence, urinary iodine, and salt iodization level in sub-Himalayan Darjeeling district of West Bengal, India. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:129-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine deficiency in district Kangra, Himachal Pradesh after 60 years of salt iodization. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:827-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of iodine deficiency in school age children in Nainital district, Uttarakhand state. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23:278-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine deficiency among children in national capital territory of Delhi – A cross-sectional study. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59:331-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine deficiency disorder in children aged 6-12 years of Ambala, Haryana. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:587-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of goitre in school children of Chamarajanagar district, Karnataka, India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2807-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine nutrition among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of a secondary care hospital: A cross-sectional study from Northern India. Indian J Community Med. 2017;42:226-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine status of pregnant women residing in urban slums of Delhi. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2018;11:506-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine nutrition among pregnant mothers in selected districts of Uttarakhand, India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:106-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Status of iodine deficiency among pregnant mothers in Himachal Pradesh, India. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1971-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early gestation screening of pregnant women for iodine deficiency disorders and iron deficiency in urban centre in Vadodara, Gujarat, India. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2014;5:63-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine nutrition status amongst neonates in Kangra district, Himachal Pradesh India. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2014;28:351-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine nutritional status among neonates in the Solan district, Himachal Pradesh, India. J Community Health. 2014;39:987-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional status and the impact of socioeconomic factors on pregnant women in Kamrup district of Assam. Ecol Food Nutr. 2012;51:463-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum copper levels among a tribal population in Jharkhand state, India: A pilot survey. Food Nutr Bull. 2005;26:309-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum zinc levels amongst pregnant women in a rural block of Haryana state, India. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:276-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude of zinc deficiency amongst under five children in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2011;78:1069-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary and non-dietary factors associated with serum zinc in Indian women. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;161:38-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:834-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors for Vitamin C deficiency in North and South India: A two centre population based study in people aged 60 years and over. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28588.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma Vitamin C status of adolescent girls in a slum of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51:932-3.

- [Google Scholar]