Translate this page into:

Longitudinal trends in physical activity patterns in selected urban south Indian school children

Reprint requests: Dr Sumathi Swaminathan, St. John's Research Institute, St John's National Academy of Health Sciences, Koramangala, Bangalore 560 034, India e-mail: sumathi@sjri.res.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

There are very few studies describing the pattern of physical activity of children in India. This study was carried out to document patterns of physical activity in south Indian school children aged 8 to 15 yr and examine changes over a one year period.

Methods:

Physical activity was assessed using interviewer-administered questionnaires at baseline (n=256) and at follow up (n=203) in 2006 and 2007. Frequency and duration of each activity was recorded and metabolic equivalents (MET) assigned. Sedentary activity included activities with MET < 1.5, and moderate-to- vigorous physical activity (MVPA) with >3.0. For each activity, daily duration, intensity (MET), and the product of the two (MET-minutes) were computed. Children were categorized by age group, gender and socio-economic status. Height and weight were measured.

Results:

At baseline, sedentary activity was higher in children aged >11 yr, while intensity of MVPA was higher in boys than girls. Over one year, physical activity at school significantly decreased (P<0.001). There was also a significant decrease in MVPA MET-min (P<0.001) with interaction effects of age group (P<0.001) and gender (P<0.001).

Interpretation & conclusions:

There was a significant decline in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity over a single year follow up, largely due to a decrease in physical activity at school. There appears to be a gap between State educational policies that promote physical well-being of school-going children and actual practice.

Keywords

Overweight

physical activity

physical education

school age population

A few studies have examined physical activity in relation to childhood overweight and obesity in developing countries, including India. In absolute terms, Asia has the highest numbers of overweight children1. Prevalence rates of between 4 to 30 per cent are reported across different regions in India2–4 although only a few of these studies have been community-based. Promoting physical activity in childhood may increase physical activity in adulthood and help reduce the burden of chronic disease. Evidence from the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study indicates that decreased physical activity levels in childhood and persistent inactivity are linked to obesity in adulthood5.

In developed countries, demographic trends of differences in physical activity with gender and age in children has been reported6–8. Specifically, The Health and Behavior of School Children (HBSC) survey conducted in 20 European countries showed that in general, boys were more active than girls and that the time spent in physically active behaviors decreased with age6.

Evidence-based research indicate that physical activity reduces adiposity in both overweight and normal children, improves musculo-skeletal and cardiovascular health and fitness, positively influences concentration and memory and thereby on intellectual performance910.

There are only a few studies which have evaluated any dimension of physical activity in Indian children1112. None have prospectively evaluated changes in physical activity with time. In this study we assessed patterns of physical activity in urban south Indian school children with respect to age, gender and socio-economic status (SES) and evaluated changes in physical activity over a one year period.

Material & Methods

Physical activity was assessed at two time-points, one year apart, in 2006 and 2007. This was done during 2 follow up visits that were part of a 3 year longitudinal study on dietary habits, food preferences and perceptions of healthy eating among urban school children13.

The Institutional Ethical Review Board approved the study and informed written consent from a parent and assent from the child were obtained. At baseline of the longitudinal study to primarily evaluate attitudes and perceptions towards diet in children, a purposive sample of 307 children aged 7 to 15 yr from three schools representing different socio-economic status (SES), were recruited into the study. Thirty children at each age from 7 to 15 yr, with additional 3-5 children to account for attrition, were recruited at baseline. Children were assessed till 15 yr of age after which they left school on completing their 10th grade. Thus, the number of children assessed at each follow up visit reduced as children left school. The total number of children 7 to 15 yr of age in the three schools was approximately 2600. The schools were chosen based on logistics of commuting and on the permission obtained from the principal. Physical activity assessments were done during the first and second follow up visits.

In relation to the present report, 256 children aged 8-15 yr were assessed for their physical activity patterns (baseline physical activity corresponding to the first year follow up of the original study), and 203 children aged between 9-15 yr were assessed at the follow up visit a year later (follow up physical activity corresponding to the second year follow up of the original study). Apart from 31 children who completed school at age 15 and were not available for the follow up visit one year later, there was a loss to follow up of 8 per cent between the two physical activity assessments. This sample size, however, was sufficient to detect a change in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity with 80 per cent power and a large effect size (Cohen's d = 2.0).

During each assessment, the preceding month's physical activity was documented using an interviewer-administered Physical Activity Questionnaire (PAQ) which was developed specifically for this study. Physical activity was comprehensively assessed across multiple domains. These included activities in school during physical education classes and recess, participation in games before or after school hours and household activities. Duration of sleep and sedentary activities such as television or video viewing and computer games, tuitions and homework were also recorded. The duration of time spent and the daily, weekly or monthly frequency of each activity was documented separately for weekdays and weekends.

The metabolic equivalent or MET (multiples of basal metabolic rate reflecting intensity of activity) was assigned for each reported activity using the Compendium of Energy Expenditure for Youth14, and a published compilation of METs15. Sedentary activity was defined16, as activity with MET levels below 1.5 and included television or video viewing, computer games, tuitions, homework and passive games. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was computed using a MET cut-off value of 3 or above17. Based on current recommendations1819, children were categorized into 2 groups based on whether they engaged in daily MVPA above or below 60 min.

The basal metabolic rate (BMR) was calculated for each child using published equations15. The duration in minutes of a specific activity was multiplied with the specific MET value to obtain a composite measure encompassing duration and intensity (MET-min). The energy expenditure for the particular activity was derived using the product of MET-min of the particular activity and the BMR per minute. The energy expenditures of all reported activities were then summed up to obtain the total daily energy expenditure. Physical activity level or PAL (ratio of 24 h energy expenditure to BMR) was calculated and cut-offs applied based on the recommendations for adults15.

At each assessment, height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight to the nearest 0.1 kg.

Statistical analysis: Data were summarized as number (%) for categorical variables and median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile) for all physical activity variables as these were not normally distributed. All physical activity variables were log transformed for all analysis. The natural log transformed values were normally distributed. Age at baseline was used to classify children into two age groups, that is, below or equivalent to 11 yr and above 11 yr. Mode of travel used by children was compared using Pearson's chi-square test. Baseline physical activity was compared between age group and gender using the Independent t test, and between tertiles of SES using one-way ANOVA. Changes in physical activity parameters over time were examined using the paired t test. Repeated measures ANOVA of all physical activity variables was performed to assess change over time with interaction effects of age group and gender also included in the model. The antilogs of estimated marginal means are presented in text and figure in measured units. For variables with significant differences, Cohen's d effect size20 was calculated using the estimated marginal means in order to compare the significant results obtained from the different analyses. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and statistical significance considered at P<0.05.

Results

Physical activity at baseline: Table I illustrates the differences in the different components of physical activity categorized according to age, gender and SES. Sleep duration was significantly lower (P<0.001) while time spent watching TV and video, and in tuitions /homework and total sedentary activity (both in terms of duration and MET-min) was significantly (P<0.01) higher in the older children (>11 yr) when compared to the younger children (<11 yr). Despite this, the older children had higher overall physical activity levels (PAL), in part, contributed to by higher activity in school (P<0.01), and longer travel MET-min to and from school (P<0.001). About 41.5 per cent of children in the older age group compared to 17.5 per cent in the younger children used active transport (walking or bicycling) to and from school (P<0.001) contributing partly to the higher physical activity levels in older children. Sports activity outside school MET-min (P<0.01) and total MVPA MET-min (P<0.01) were significantly higher in boys than girls, although the duration spent in MVPA was similar, indicating that the intensity of physical activities was much higher in boys. Approximately 53.1 per cent children were engaged in MVPA of > 60 min. Socio-economic status was not associated with any differences in physical activity.

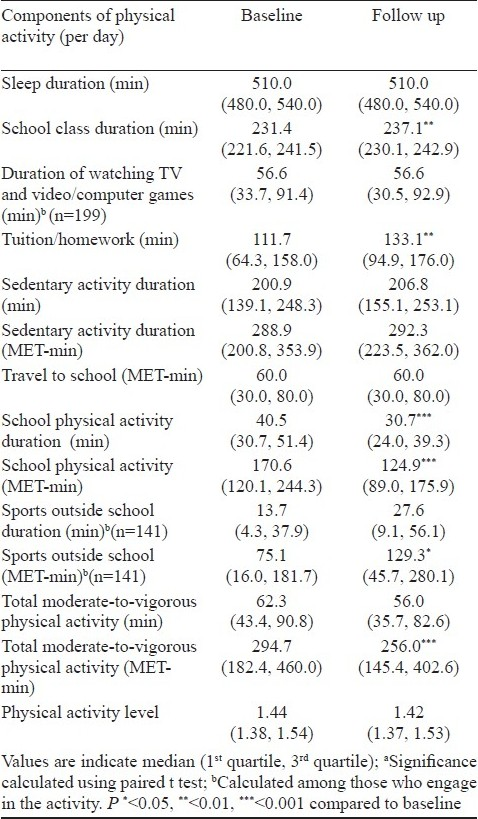

Within subject change in physical activity patterns over one year: There was a significant increase in the duration of tuition (P<0.001) and school classes (P<0.01), but a significant reduction in the duration and MET-min of school physical activities (P<0.001) and total moderate-to-vigorous physical activity MET-min (P<0.001) from baseline to follow up (Table II). About 18 per cent of participants at baseline and 19 per cent at follow up did not take part in any sports outside school, while about 1 per cent did not view TV or video on both occasions.

Temporal changes in physical activity patterns were further assessed using a repeated measure ANOVA, with interactions of time, gender and age included in the model. This analysis indicated a significant age group by time interaction for duration of sleep (P<0.001), TV and video viewing (P<0.001), tuition/homework (P=0.001), and MET-min of total sedentary activity (P<0.001). Sleep duration decreased, while TV/ video viewing, tuitions/homework and total sedentary activity increased with age. School physical activity decreased significantly (P<0.001), a marked decrease being observed in girls. While PAL remained constant with time, there was a significant interaction effect of gender with time (P<0.001). Thus, the mean of PAL declined from 1.46 (CI: 1.44 - 1.49) to 1.41 (CI: 1.38 - 1.42) in girls (Cohen's d effect size of 0.53) while there was no change in PAL in boys. There was also an interaction effect of age with time (P= 0.004); PAL increased in the younger age group, but declined in the older children.

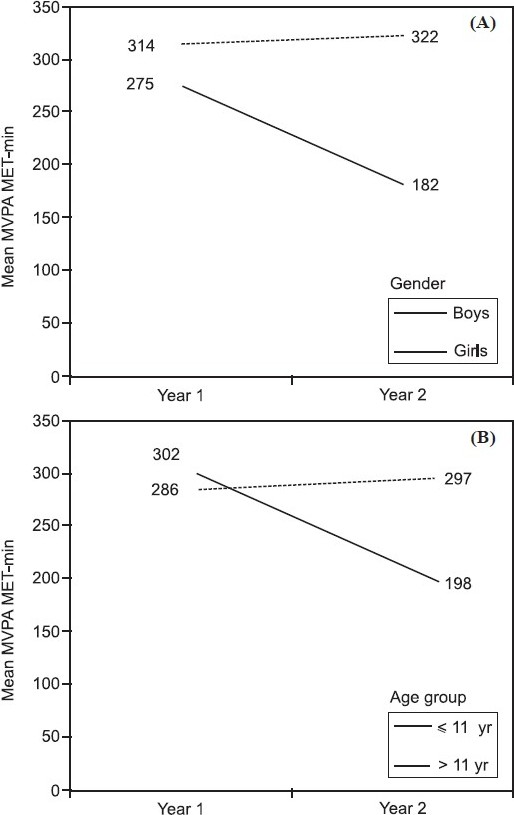

The duration of time spent in MVPA showed a significant decrease over time (P=0.004) with an interaction effect of age (P<0.001) and gender (P=0.004). The mean duration of time spent by the older children in MVPA decreased from 63 min (95% CI: 57-70) to 45 min (95 % CI: 41-51), while it remained almost the same with 64 min (95 % CI: 57-70) at baseline to 66 min (95% CI: 60-72) at follow up in the younger children. In girls, the MVPA duration decreased from 61 (95% CI: 55-68) to 46 min (95% CI: 42-51) while it remained the same in boys (65 min). MVPA MET-min indicated that intensity decreased significantly (P=0.002) over time with an interaction effect of age and gender (P<0.001 each) with time. These interactions were due to decrease in MVPA MET-min in girls alone and in the older children. There was a marginal increase in boys from 314 (95 % CI: 277-357) to 322 (95% CI: 283-366), while in girls, it decreased significantly from 275 (95 % CI: 243-311) to 182 (95% CI: 161-206) with a large effect size of 1.32 (Fig. A). Similarly, there was a decline in the estimated marginal means of MVPA (MET-min) from 302 (95 % CI: 265-344) to 198 (95 % CI: 173-226) in children in the older age group (effect size of 1.33), while in the younger age group it remained at 286 (95 % CI: 254-322) at baseline and at 297 (95 % CI: 263-335) at follow up (Fig. B). At baseline, 53.1 per cent (58.0% boys and 48.9% girls) of children were engaged in daily MVPA of 60 min and above, while at follow up this reduced to 45.3 per cent (55.7% boys and 35.8% girls).

- Gender and age related changes in estimated marginal geometric means of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) MET-min during two assessments one year apart in 2006 (year 1) and 2007 (year 2). Fig. (A) indicates changes in boys and girls, while Fig. (B) shows changes with age.

Discussion

At baseline, sedentary activity was higher in the older children and boys reported more moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than girls. These data are in agreement with reports from developed countries that have shown that younger children and boys are more likely to be active, and that participation in sports is lower in girls2122.

The temporal data of our study indicated that there was a significant increase in homework/tuitions after school and a significant decrease in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Several studies in developed countries have indicated that physical activity declines with increasing age821–23 including studies which have used objective measures of physical activity, such as accelerometers22. In this study the decline in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in girls and older children was not only due to a reduction in duration but also the intensity of physical activity at school.

This was offset to some extent in boys, who increased their physical activities outside school, albeit at a lower intensity. However, overall physical activity levels were at the sedentary level for all children and this is particularly a matter of great concern in the long term, with the likelihood of physical activity tracking into adulthood. Physical education at school is a major determinant of physical activity for urban children as a third of the day is spent in school. While norms for physical education in schools have been described, adherence to these norms is generally low, globally24. Data in India are limited, although available data suggest that basic amenities, such as playgrounds are often lacking in Indian schools25. The National Policy on Education26 and the NCERT position paper27 emphasize the integration of sports education in the curriculum, but the implementations of these policies is generally low. A review of interventions28 has indicated that in the short term, the school setting is effective in increasing physical activity. Physical education programmes at school should, therefore, be strengthened to ensure effective participation of all children at adequate levels of physical activity.

Since sustainability of physical activity is a desirable goal to prevent later chronic disease, the home and community environments need to be examined for barriers to activity outside school. Exposure to a variety of leisure time activities which children enjoy may ensure participation in active games that can be sustained through adulthood29. This is particularly important in India given that India is often described as the emerging diabetes capital of the world30, that South Asians typically have an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) earlier than other ethnic groups in the world and that this earlier onset of AMI is related to an increased prevalence of risk factors, including decreased physical activity, at an earlier age31.

While more objective measures of physical activity exist, the physical activity questionnaire, which was used in this study allowed for the assessment of activities across various domains of physical activity. This would not have been possible using the current objective measures in isolation. However, one limitation is the possibility of over-reporting, particularly with self-reports of physical activity. Using objective measures, which are preferable to self-report for assessment of physical activity, it is possible to isolate MVPA by period (for example, to distinguish between school MVPA and non-school MVPA). Self-report in addition to this would give more specificity regarding domains of physical activity.

To examine internal consistency in data, the parameter school activity which is the most structured and the least variable activity was chosen. At baseline, the coefficient of variation in school activity at each age was low at 10 per cent indicating considerable consistency in reporting. In addition, reporting of school activity for a particular age at baseline was compared with that reported at the same age at follow up (that is, 9 yr old children at baseline versus 9 yr olds at follow up). The activity was not significantly different between the time points (P>0.05), indicating consistency in reporting between the two visits. While this study provides data on individual behaviour, future studies need to assess familial and community level factors which have important influences on individual behaviour.

In conclusion, there was a significant decline in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in urban school children largely due to a decrease in physical activity at school. This was particularly true of girls and older children. The study underscores the importance of implementing State educational policies that seek to promote the physical well-being of children.

The authors acknowledge all the participants of the study and the staff who helped in data entry. The study was supported through intra-mural funding.

References

- Prevalence and trends of overweight among preschool children in developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1032-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth pattern and prevalence of obesity in affluent schoolchildren of Delhi. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:485-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Childhood obesity in Asian Indians: a burgeoning cause of insulin resistance, diabetes and sub-clinical inflammation. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(Suppl 1):172-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obesity in Indian children: time trends and relationship with hypertension. Natl Med J India. 2007;20:288-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of obesity in relation to physical activity tracking from youth to adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:919-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Currie C, Morgan A, Smith R, Settertobulte W, Samdal O, Rasmussen VB, eds. Young people's health in context: Health behavior in school-aged children (HSBC) study: International report from the 2001/2002 survey. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- Continuity and change in sporting and leisure time physical activities during adolescence. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32:53-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:709-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Television viewing and sleep are associated with overweight among urban and semi-urban South Indian children. Nutr J. 2007;6:25-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting prevalence of overweight among 12- to 17-year-old urban adolescents in Hyderabad, India. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:1384-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dietary patterns in urban school children in south India. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:593-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a compendium of energy expenditures for youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:45-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Human energy requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. In: Food and Nutrition Technical Report Series. Rome 17-24 October 2001. Rome: FAO; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In: Promoting physical activity: A guide for community action. Champaign II: Human Kinetics: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Physical activity for everyone. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/index.html

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1977.

- [Google Scholar]

- How do school-day activity patterns differ with age and gender across adolescence? J Adolesc Health. 2009;44:64-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 yr. JAMA. 2008;300:295-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:350-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Elementary education in India.Analytical Report 2005-06. New Delhi, India: National University of Educational Planning and Administration and Department of School Education and Literacy, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India; 2007. p. :1-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Government of India. National Policy on Education, 1986 (as modified in 1992) New Delhi: Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development; 1998.

- [Google Scholar]

- NCERT. Position paper 3.5. National Focus Group on health and physical education. New Delhi: National Council for Educational Research and Training; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Promoting physical activity participation among children and adolescents. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:144-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal study of the number and choice of leisure time physical activities from mid to late adolescence: implications for school curricula and community recreation programs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:1075-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mortality in diabetes mellitus: revisiting the data from a developing region of the world. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:225-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for early myocardial infarction in South Asians compared with individuals in other countries. JAMA. 2007;297:286-94.

- [Google Scholar]