Translate this page into:

Knowledge & attitudes of mental health professionals regarding psychiatric research

Reprint requests: Dr N.N. Mishra, GRIP-NIH Project, Room # 30, Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER-Dr RML Hospital Park Street, New Delhi 110 001, India e-mail: drmishrarml@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Mental health professionals have varied attitudes and views regarding informed consent and confidentiality protections in psychiatric research and clinical care. The present study was designed to understand the knowledge and views of mental health professionals (MHPs) regarding informed consent and confidentiality protection practices.

Methods:

Mental health professionals (n=121) who were members of the Delhi Psychiatric Society, were invited to participate in this questionnaire-based study of their knowledge and attitudes regarding informed consent and confidentiality. Half of them expressed willingness to discuss participation and gave initial oral consent (n=62); of these, 31 gave written informed consent to participate and completed the questionnaires. The questionnaires included both forced choice (yes / no / do not know) and open-ended questions. Questionnaires content reflected prominent guidelines on informed consent and confidentiality protection.

Results:

Attitudes of the majority of the participants towards informed consent and confidentiality were in line with ethical principles and guidelines. All expressed the opinion that confidentiality should generally be respected and that if confidentiality was breached, there could be mistrust of the professional by the patient/participant. The mean knowledge scores regarding informed consent and confidentiality were 8.55 ± 1.46 and 8.16 ± 1.29, respectively.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The participating mental health professionals appeared to have adequate knowledge of basic ethical guidelines concerning informed consent and confidentiality. Most respondents were aware of ethical issues in research. Given the small sample size and low response rate, the significance of the quantitative analysis must be regarded with modesty, and qualitative analysis of open-ended questions may be more valuable for development of future research. Increased efforts to involve mental health professionals in research on ethical concerns pertinent to their work must be made, and the actual practices of these professionals with regard to ethical guidelines need to be studied.

Keywords

Confidentiality

ethical guidelines

informed consent

mental health professionals

mental health research

Informed consent is a legal and ethical duty in general medical and psychiatric treatment and in research with human subjects123. In the context of treatment, informed consent seeks to protect patients’ wellbeing and respect their autonomy. In research, its goal is to enable potential research subjects to protect their own interests, while respecting their right of self-determination1. Different national and international guidelines for research conduct4, including that of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in India5, emphasize the necessity of obtaining informed consent for research participation.

In the area of mental health, some psychiatrists believe that the mentally ill cannot provide informed consent; hence they are sometimes more opposed to the research participation of individuals with mental illness than patients themselves or their family members6. But even patients with severe mental illnesses are frequently capable of providing meaningful informed consent7. It has been argued “that because psychiatric patients might not benefit from research in which they participate, psychiatric research involves a separate set of ethical conditions for research than treatment”89. Others, like Davies himself8, argue that the ethical grounds for psychiatric research namely, respect for autonomy and concern for justice are the same as those for treatment, and that obtaining informed consent from those with psychiatric conditions is possible and necessary8.

Management of patient information regarding mental illness is challenging issue in mental healthcare and research. Patients have right to know and control all information regarding their health, but at the same time they fear stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness10.

Potential violations of confidentiality that would seem to benefit patients or to be necessary for their care present especially perplexing conflicts for mental health professionals who want to act in their patients’ interests. In India, as elsewhere, mental health professionals are approached by families and other agencies for patients’ health data. Especially in individualistic Western countries and cultures, because the confidentiality of patient information is stressed during the training of mental health professionals, they will typically not share information with family members of mentally ill patients even when doing so may be of benefit to those patients. In contrast, according to Leggatt11, in Eastern cultures, family members traditionally play an integral role in the care of patients with mental illness, so information must be shared with them if patients are to receive care. While stigma of mental illness may be even greater than in the West, confidentiality protection with regard to family members is perceived as less of a problem, and greater weight is placed on the value of family involvement in mental health treatment for the sake of the patient's recovery11.

There is a paucity of information on the knowledge of and attitudes of mental health professionals towards ethical issues in psychiatric research. Among the few studies, Hariharan et al12 surveyed various health professionals regarding knowledge, attitudes and practices towards care-ethics. In a recent study comparing attitudes of health professionals to those of legal professionals, the former gave more importance to confidentiality and autonomy of patients over the security of themselves and others13.

Thus, while autonomy and confidentiality are valued in most cultures, their meaning or demands may be different in different cultures. In India, an individual's identity is intimately connected to his or her family; family is integral to one's self14. The question of protecting personal privacy and the confidentiality of personal information is thus complicated when other individuals are so integral to one's self. Therefore, it is necessary to know how mental health professionals, including those who conduct research, view confidentiality. The present study was carried out to understand the views of mental health professionals (MHPs) regarding informed consent and confidentiality.

Material & Methods

This questionnaire-based study was conducted in the Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER-Dr RML Hospital, New Delhi, India, during 2009-2010. All psychiatrists and psychologists who were members of the Delhi Psychiatric Society (DPS) and listed with full contact information in the DPS Directory (n= 121) were invited to participate in this study. A little more than half (n=62) responded and were contacted by phone. Details of the study were explained to them, and they gave initially oral informed consent to participate.

Two questionnaires were developed. One assessed knowledge of informed consent guidelines and attitudes toward obtaining informed consent, including from individuals with mental health conditions. The second assessed knowledge of guidelines regarding confidentiality protection and attitudes relevant to their interpretation and implementation. Each section contained ten questions (one section contained eleven), for a total of 41 closed-ended questions. True/false questions were used to assess knowledge, while agree /disagree/do not know were the options in the attitude assessment sections. At the end of each questionnaire, an open ended question was included to invite participants to express their attitudes towards informed consent and confidentiality.

The questionnaires were given to the participants in person and at that time written informed consent was obtained. Some completed the questionnaires immediately and returned to the investigators while others said they would complete the questionnaire at their convenience. Ultimately, only half of the 62 professionals who had expressed initial willingness to participate completed the questionnaire (n=31; psychiatrists: n=26, psychologists, n=5).

Results

Demographic details: The mean age of participants was 40.2 ± 10.9 yr, and mean duration of professional experience was 13.2 ± 10.9 yr. There were 24 male and 7 female participants. The participating psychologists and psychiatrists were comparable on demographic variables and range of years of experience; however, statistical comparisons between the responses of members of these groups were not feasible due to the small number of participating psychologists.

Knowledge of informed consent: For the knowledge assessment questions, each correct answer was given a score of one with a maximum of 10. All scores were added to calculate final scores regarding participants’ knowledge of ethics guidelines and informed consent. The mean knowledge scores regarding informed consent and confidentiality were 8.16 ± 1.29 and 8.55 ± 1.46, respectively. There was no relation between duration of professional experience and knowledge about informed consent guidelines among these participants.

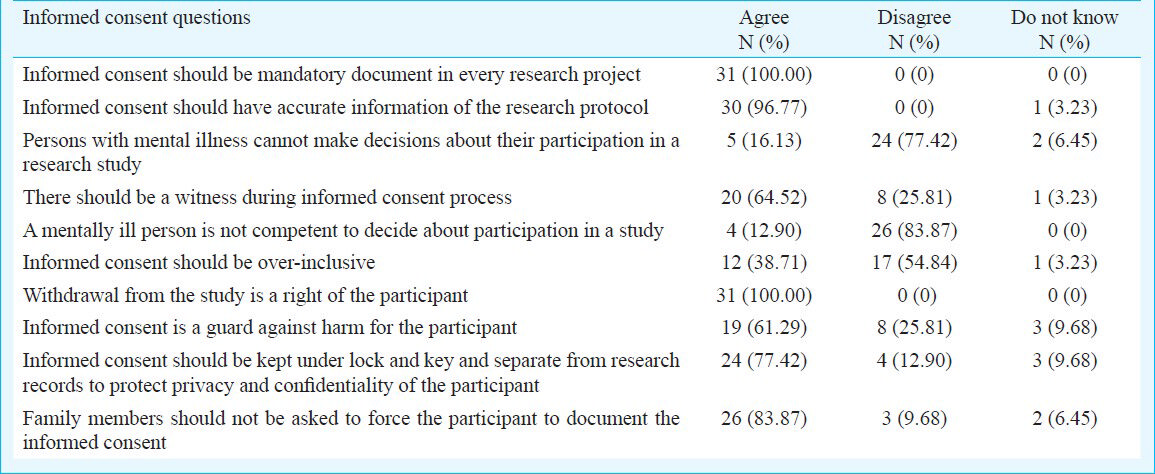

Attitudes regarding informed consent: All were of the opinion that informed consent should be a mandatory document in every research project. All but one (who was uncertain) agreed that informed consent should have accurate information about a research protocol. On all other questions opinions varied (Table I). Approximately a quarter did not think that informed consent was a safeguard against harm to participants.

Knowledge of confidentiality guidelines: Correct answers for individual questions received one mark, and the scores were summed up to yield the final knowledge score. The mean knowledge score on the confidentiality questionnaire was 8.65 ± 1.45. Knowledge of confidentiality was not influenced by duration of experience of the mental health professional in the field.

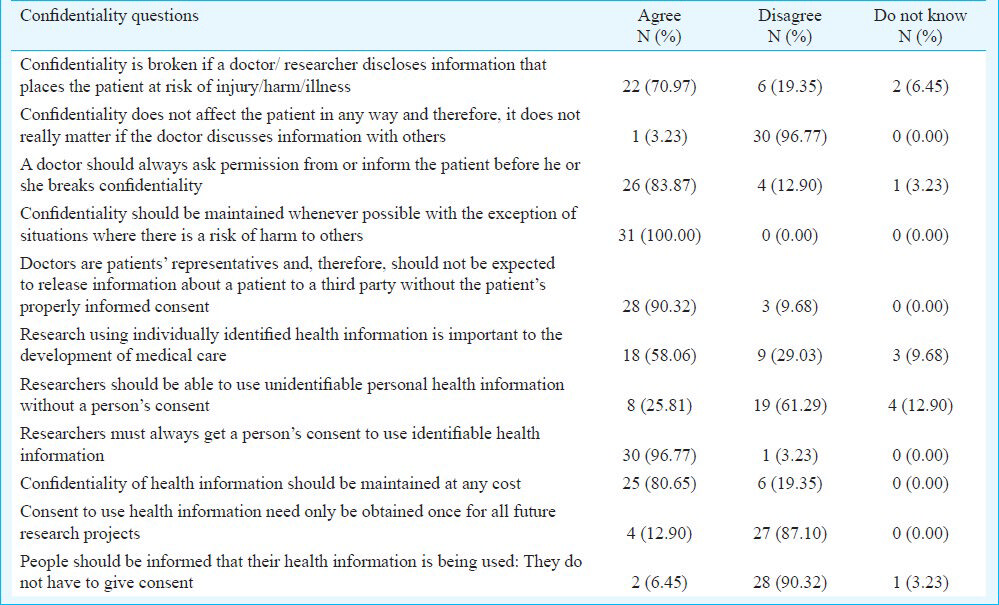

Attitudes regarding confidentiality guidelines: All agreed that “confidentiality should be maintained whenever possible with the exception of situations where there is a risk of harm to others.” The majority (90%) agreed that “doctors are patients’ representatives and, therefore, should not be expected to release information about a patient to a third party without the patient's proper informed consent”. About 60 per cent of participants agreed that “research using individually identified health information is important to the development of medical care”. Some (26%) felt that “researchers should be able to use unidentifiable personal health information without a person's consent.” Eight (26%) participants did not agree with the statement that there should be a witness during the informed consent process.

Participants were also asked to provide detailed opinions regarding confidentiality and informed consent. Some of them opined that confidentiality should be maintained in all situations, particularly with regard to HIV infection. Some felt that confidentiality could be breached in exceptional situations, but most did not elaborate what these situations would be. However, one participant wrote that “confidentiality is a right of the patients and must be maintained in all situations - clinical or research except in a few conditions like risk of harm to others”.

Some participants expressed the view that spouse and family members should be told about a patient's illness especially in case of psychiatric illness. A participant stated that “confidentiality should be maintained at all costs but the information can be given to others without patients’ consent when such information can be helpful to the community”.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that participating mental health professionals knew about informed consent and confidentiality guidelines and issues in research, and had positive attitudes towards fulfilling these important ethical requirements. However, only approximately a quarter of those professionals who were eligible to participate and only half of those who expressed initial willingness to do so-completed the study. This might have introduced some bias.

With regard to attitudes towards informed consent, all participants agreed that the process of obtaining informed consent should be mandatory and accurate information should be presented, but opinions were divided on the amount of information that should be provided to potential participants. It is worth noting that participants considered informed consent to be a form or document, rather than a process that is documented by execution of a consent form, a mistake or a limited view that various commentators note1. Regarding attitudes towards confidentiality there was relatively little variability. All were of the opinion that confidentiality is important and should be maintained. Several respondents felt that right to confidentiality ends where the safety of others begins, for instance, in the case of HIV infection, but generally did not specify what magnitude of risk of harm to others could justify breaching confidentiality.

There was a great divergence of opinion regarding the permissibility of research employing identifiable and unidentifiable information. This divergence indicates a need for additional training about existing guidelines that prohibit use of identifiable participant information without participants’ consent, limit the use of identifiable information, and explain consent requirements and procedures for using de-identified or anonymized research data and biological samples. A few responses to the open-ended question also demonstrated confusion or seemingly contradictory opinions regarding confidentiality, for example, stating that “confidentiality should be maintained at all costs,” but also that confidentiality may be breached for the benefit of “the community”.

In the open-ended comments section, respondents offered reasons for maintaining confidentiality. Some stressed that confidentiality was a right of the patients. Some emphasized the benefits resulting from maintenance of confidentiality, such as avoiding stigma and discrimination associated with health conditions, including psychiatric conditions.

The participants revealed views about the scope of patient or research subject privacy protected by a professional's duty of confidentiality. Some were of the opinion that family members who are primary caretakers should be told about the nature of illness that their relatives have. The apparent rationale for breaching an individual patient's confidentiality with regard to the family was to benefit and provide support for the patient. This view reflected the belief that doctors, families and patient should collaborate for better treatment.

This study had several limitations. Only knowledge and stated opinion were assessed, not the actual practice. This difference between knowledge or opinion and actual practice is important, as it is actual practice that affects the rights and welfare of patients and research participants. Atac15 reported that all physicians in his study on attitudes towards consent thought consent should always or generally be obtained, but less than 50 per cent obtained it in practice. This was because they thought that patients might not understand the informed consent form. Similarly, Yousuf et al16 studied doctors in India and Malaysia and observed that though awareness of informed consent was high in India (Kashmir), physicians practiced medical paternalism in clinical decision making by ignoring their patient's autonomy.

In summary, the participating mental health professionals appeared to have adequate knowledge of basic ethical principles and guidelines concerning informed consent and confidentiality. Most respondents were aware of ethical issues in research. As more research studies, especially clinical trials are initiated in India, it is necessary to study whether professionals and researchers really attend to these issues in practice. Though knowledge itself is a critical prerequisite, it is important to ensure that actual practice reflects stated knowledge and attitudes.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the support from the Fogarty International Center, NIH Training Program for Psychiatric Genetics in India, Grant #5D43 TW006167-02 and ICMR - NIH Long Term Training Programme for Bioethics Development in India, Grant # 2 R TW007093.

References

- Informed consent: Legal theory and clinical practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging findings in ethics of schizophrenia research. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:111-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) 1993. Geneva: International Guidelines for Biomedical Research involving Human Participants; Available from: www.cioms.ch

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research on Human Participants. 2006. New Delhi: ICMR; Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- The need for additional safeguards in the informed consent process in schizophrenia research. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:647-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Professionals’ responsibilities in releasing information to families of adults with mental illness. Psychiatric Service. 2003;54:1622-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Families and mental health workers: the need for partnership. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:52-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare personnel towards Care-Ethics: a perspective from the Caribbean. 2006. Internet J Law Healthcare Ethics. 5 Availabe from: http://ispub.com/IJLHE/1/9466

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical and legal professionals’ attitudes towards confidentiality and disclosure of clinical information in forensic settings: a survey using case vignettes. Med Sci Law. 2013;53:132-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of the opinions and behaviors of physicians with regard to informed consent and refusing treatment. Mil Med. 2005;170:566-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Awareness, knowledge and attitude toward informed consent among doctors in two different cultures in Asia: a cross-sectional comparative study in Malaysia and Kashmir, India. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:559-65.

- [Google Scholar]