Translate this page into:

Intervention strategies to reduce the burden of soil-transmitted helminths in India

For correspondence: Dr Sitara Swarna Rao Ajjampur, Division of Gastrointestinal Sciences, Wellcome Trust Research Laboratory, Christian Medical College, Vellore 632 004, Tamil Nadu, India e-mail: sitararao@cmcvellore.ac.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections continue to be a major global cause of morbidity, with a large proportion of the burden of STH infections occurring in India. In addition to direct health impacts of these infections, including anaemia and nutritional deficiencies in children, these infections also significantly impact economic development, as a result of delays in early childhood cognitive development and future income earning potential. The current World Health Organization strategy for STH is focused on morbidity control through the application of mass drug administration to all pre-school-aged and school-aged children. In India, the control of STH-related morbidity requires mobilization of significant human and financial resources, placing additional burdens on limited public resources. Infected adults and untreated children in the community act as a reservoir of infection by which treated children get rapidly reinfected. As a result, deworming programmes will need to be sustained indefinitely in the absence of other strategies to reduce reinfection, including water, hygiene and sanitation interventions (WASH). However, WASH interventions require sustained effort by the government or other agencies to build infrastructure and to promote healthy behavioural modifications, and their effectiveness is often limited by deeply entrenched cultural norms and behaviours. Novel strategies must be explored to provide a lasting solution to the problem of STH infections in India other than the indefinite provision of deworming for morbidity control.

Keywords

Ascaris

hookworm

India

mass drug administration

soil-transmitted helminths

Trichuris

WASH

Introduction

Soil-transmitted helminth (STH) infections are the most prevalent neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) globally, with 1.22 billion people estimated to be infected12. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a strategy of mass drug administration (MDA) of preventive chemotherapy to all 875 million children worldwide at risk of STH infection3. In India alone, 225 million children are estimated to be at risk of STH4. The STH includes human hookworm species (Ancylostoma duodenale & Necator americanus), roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides) and whipworms (Trichuris trichiura). Although A. lumbricoides has been reported to be the most prevalent STH infection56, human hookworm infections are responsible for the majority of the morbidity, as measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALY's) or years lived with disability57. In pregnant women, STH infections have been associated with intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight8910. Morbidity associated with hookworm infections includes iron deficiency anaemia and protein loss and further exacerbation of pre-existing nutritional deficiencies in susceptible populations11. Infection with Ascaris and Trichuris species is also associated with increased risk of stunting, protein-energy malnutrition, decreased physical performance and lower body mass index in children1213. While the impact of hookworm infections appears to disproportionately affect children, women in the reproductive age group and pregnant women in resource-poor settings, the prevalence of hookworm infection is greatest in adults who are not treated under the current morbidity control guidelines814151617.

Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and burden of disease in India

India has the highest burden of STH infections globally18. Studies on the prevalence of STH in the Indian subcontinent have been reviewed recently and suggest that the prevalence of STH infections may exceed 50 per cent in school-aged children (SAC) in six States of India619. These reviews have demonstrated considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence and burden of STH, likely due to diverse climactic and geographic conditions, socio-demographic status and behavioural and cultural practices of the population519. Although many studies on the prevalence of STH have been carried out in the country, very few have attempted to estimate the prevalence in age groups other than SAC202122. Differences in study methods, age groups and types of populations studied have also contributed to the wide variation in the reported prevalence and intensity of STH infections in India.

More recent estimates from surveys carried out in the past decade include a study in 20 schools from four districts of Bihar by Greenland et al23, which demonstrated an overall prevalence of 67.90 per cent in SAC (Ascaris 51.90%, hookworm 41.80%, Trichuris 4.70% with 26.70% dual infection) and most infections were of light intensity. Ganguly et al24 carriedout a study in SAC in 27 districts of Uttar Pradesh in a total of 130 schools and found an overall prevalence of 75.60 per cent (Ascaris 69.60%, hookworm 22.60%, Trichuris 4.60%) although most of these infections were of light intensity. Additional school-based surveys in multiple States have been carried out in SAC in Madhya Pradesh (14.76%, Ascaris 9.84%, hookworm 4.92%), Rajasthan (21.10%, Ascaris 20.20%, hookworm 1.00%, Trichuris 0.20%) and Chhattisgarh (74.60%, Ascaris 70.40%, hookworm 10.50%, Trichuris (0.05%)252627. In the south, studies showed a higher prevalence for hookworm both in SAC (6.30%) and when all age groups were surveyed (38.00%) than Ascaris (1.50 and 1.20%)2028. Taken together, there are sufficient data to demonstrate that the current STH prevalence is high and both control of morbidity and strategies to potentially interrupt transmission are of high public health significance in India.

Recommended control strategies

The WHO strategic plan 2011-202029 for the control and eventual elimination of STH infection includes preventive chemotherapy of at-risk populations in endemic areas, health and hygiene education focussing on behavioural modification to reduce transmission and provision of adequate sanitation. The WHO guidelines emphasize targeted deworming programmes aimed at ‘at-risk’ populations including children (greater than one year of age), non-pregnant adolescent girls (10-19 yr), non-pregnant women of the reproductive age group (15-49 yr) and pregnant women (second and third trimester) to control morbidity associated with these infections29. In areas where the baseline prevalence of any STH infection is greater than 20 per cent, the recommendations are an annual single dose of albendazole (400 mg; 200 mg for children 1-2 yr of age) or mebendazole (500 mg). In areas where the baseline prevalence is greater than 50 per cent, the recommendation is biannual deworming. In addition, if the prevalence of anaemia is greater than 40 per cent among pregnant women, deworming is conditionally recommended29. In India, deworming is carried out with albendazole, which has been shown to have highly effective cure rates for Ascaris and hookworm infection but less so for Trichuris infections30. The National Deworming Day programme was initiated by the Indian government in February 2015 with the aim of deworming every child between 1 and 19 yr of age biannually and is one of the largest national public health programmes in the world31. While there has been considerable debate regarding the effectiveness of mass deworming programmes in the academic community323334, several studies conducted in India have suggested benefit.

The effect of mass treatment for ascariases was recognized in early studies carried out in India by Gupta et al35 in the 1970s. In this study, where undernourished pre-SAC (PSAC) were randomized to receive either tetramisole every four months or placebo, the prevalence of Ascaris decreased in the treatment group (although it was not eliminated) and the nutritional status of the children receiving treatment improved significantly at 8-12 months. In addition, there are several observational studies that have shown improvements in multiple outcomes including weight and haemoglobin levels in children in communities following deworming143234. However, treatment of infected individuals and subsequent resolution of infection do not prevent recurrence of infection. STH infections are over-dispersed in populations, with approximately 80 per cent of infections harboured by 20 per cent of the population1. As a result, populations in endemic areas have high rates of reinfection following deworming36. Surveys in all age groups indicate that adults have high rates of hookworm infections in these communities and likely act as a reservoir of infection1137. Although the drugs used in the MDA programmes are now available off patent and significant drug donation programmes have been put in place following the London Declaration on NTDs38, national programmes still require substantial logistical and financial investment by developing countries.

Environmental reservoirs have also been shown to contribute to the high rates of reinfection3940. The lack of access to safe drinking water, open defecation practices, and poor hygiene practices are risk factors for poor gastrointestinal health, including STH infection, in India41. Water, hygiene and sanitation (WASH) interventions consist of a multi-pronged approach which includes community management of water resources, empowering local bodies and private agencies to increase capacities for procuring safe drinking water, promotion of hand hygiene and provision of latrines42. The ‘Swachh Bharat Abhiyan’ programme (http://swachhbharatmission.gov.in/sbmcms/index.htm) is an example of a large government-led initiative which provides funds for villages to construct toilets and prevent open defecation.

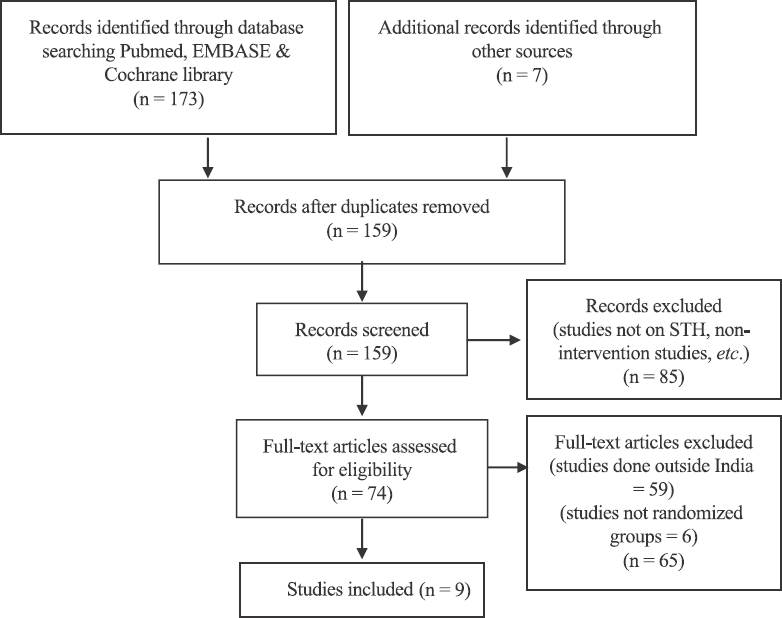

An attempt was made to identify all relevant studies (published and available in full text) conducted in India since 1995 that involved community-based interventions to reduce the prevalence of STH, reduce the burden of disease or potentially interrupt transmission of STH in the community. An online search was conducted on PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane library with the following search terms: (soil transmitted helminths) OR Ascaris) OR Hookworm) OR Trichuris) AND (intervention OR deworming OR WASH OR health education) AND India. A total of 74 full text articles were assessed for eligibility and only nine were included in this review (Figure).

- Flowchart showing selection of studies.

Studies on intervention strategies in India

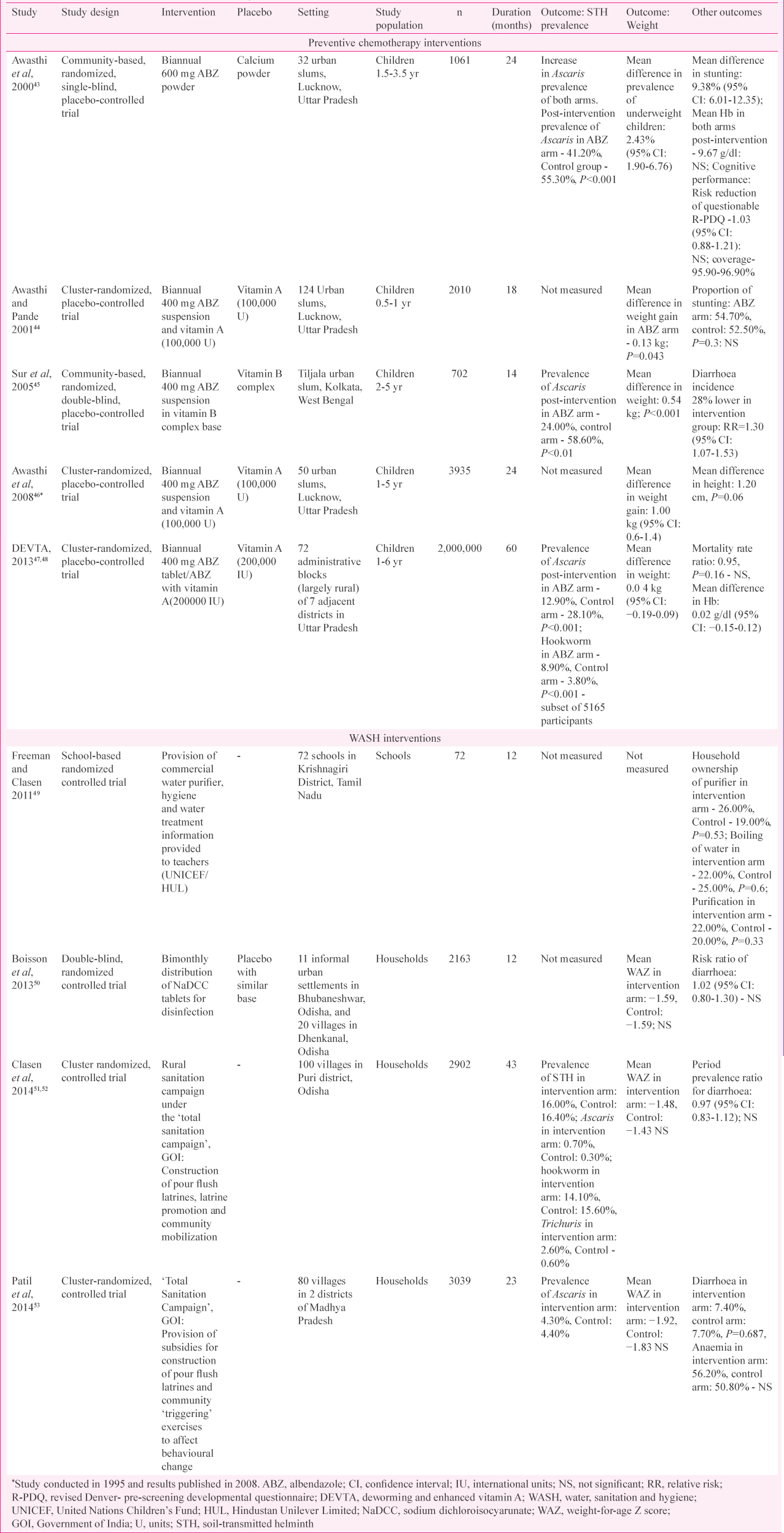

The trials involving community-based interventions to reduce the prevalence of and/or morbidity associated with STH infection in India over the past two decades were reviewed from the currently available literature Table. Although several studies on the prevalence of STH have been conducted, only five randomized control trials (RCTs) of preventive chemotherapy with MDA of albendazole and four studies on WASH interventions have been carried out in India.

Mass drug administration (MDA) interventions

Among the studies of MDA434445464748, all involved biannual treatment of PSAC or SAC under-five years of age and a majority were conducted in Uttar Pradesh. A single MDA RCT was conducted in West Bengal45. All studies involved co-administration of a vitamin or other supplement that was also received by the control group. Other than the large DEVTA trial conducted in rural administrative blocks in Uttar Pradesh in about two million children47, all the other studies recruited about 1000-4000 children in urban slums followed up for a period of 1-2 years43444546. When parasitological outcomes were measured (3 of 5 trials), the prevalence of Ascaris was reduced by more than half in the treatment arm in the Kolkata trial (53.90-24.00% in the intervention arm) with large effects seen for ascariasis at three months post albendazole administration (Ascaris 24.00% in intervention & 58.60% in control, P<0.01)45. The DEVTA trial also demonstrated significant reductions in STH prevalence following MDA (Ascaris 12.90% in intervention & 28.10% in control, P<0.001; hookworm 3.80% in intervention and 8.90% in control, P<0.001)4748. At the end of the study period, none of the studies that measured STH prevalence post-intervention demonstrated prevalence less than 15 per cent, despite high reported treatment coverage (96.90%)43. Rapid reinfection with STH following deworming is the plausible explanation for the lack of long-term positive outcomes in such interventions. A study in slum children in Vishakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, in 1998 showed that the disease prevalence returned to pre-treatment levels within nine months following deworming; however, the intensity was lowered54. Jia et al36 also published a meta-analysis that illustrated the rapid rate of reinfection for STH post-deworming. From an analysis of 51 studies, they concluded that Ascaris infection reached 68 per cent [95% confidence interval (CI) 60-76] of pre-treatment prevalence six months post-deworming, hookworm 55 per cent (95% CI: 34-87) and Trichuris 67 per cent (95% CI: 42-100)36.

Since the introduction of government-run MDA for lymphatic filariasis (LF) in endemic areas in 1998 in Tamil Nadu, several observational studies have documented the impact of mass interventions for STH in the community55565758. In Villupuram district, Tamil Nadu, community-wide MDA with albendazole and diethylcarbamazine (DEC) resulted in a decrease of STH (measured in a subgroup of children aged 9-10 yr) from 60.40 to 15.60 per cent [percentage reduction of Ascaris - 74.30% in intervention arm (albendazole with DEC) and 30.80% in control (DEC alone), hookworm reduction of 89.50% in intervention arm and 25.99% in the control arm, Trichuris reduction of 81.58% in intervention arm and 77.25% in the control arm]55. There was also a difference in intensity of STH infection (measured as eggs per gram by the Kato-Katz technique) with an egg reduction rate of 97.34 per cent in the intervention arm and 79.02 per cent in the control arm (Ascaris - 96.55% in intervention arm and 76.64% in control arm; hookworm - 94.18% in intervention arm and 36.05% in control arm; and Trichuris - 83.96% in intervention arm and 85.57% in control arm)55. A bounce back in STH infection levels was seen following treatment, but the difference in prevalence between albendazole and DEC- treated SAC compared to DEC-treated SAC remained significant (34.56% prevalence of STH in the intervention arm and 59.60% in control arm 11 months post-MDA) (P<0.005)56. A subsequent study demonstrated that biannual MDA had greater benefit in keeping the prevalence of STH low following treatment (14.15% in intervention arm and 50.25% in control arm, 11 months post-two rounds of MDA, P<0.001)57. After seven annual rounds of LF MDA from March 2001 to February 2010, STH prevalence was 12.48 per cent in the intervention arm, with hookworm showing the largest reduction with a final prevalence of 1.17 per cent, Ascaris 10.92 per cent and Trichuris 1.17 per cent (P<0.05)58. Similar findings have also been reported in a meta-analysis of 38 studies by Clarke et al59, where they observed that mass deworming of entire communities was a superior strategy to targeted deworming for the reduction of STH prevalence in children. The pattern of rapid fall in prevalence and bounce back/reinfection has been included in mathematic modelling studies by Anderson et al6061 to formulate strategies to break transmission and further demonstrate the advantage of mass deworming of the community at high coverage levels over targeted deworming.

In addition to measuring impacts on STH prevalence, other outcomes evaluated in these studies included effects on malnutrition (anthropometry), anaemia and cognitive function4347. In three studies conducted in India, deworming interventions resulted in a significant mean weight gain in children in the intervention arm444546. These findings were consistent with the results reported elsewhere6263. In addition to these direct effects on treated children, several studies also suggested indirect ‘spillover’ benefits from deworming programmes that resulted in positive outcomes in siblings of the children who received the drug and positive educational outcomes in untreated children in schools where deworming was done6465. However, the largest clinical trial to date, the DEVTA trial, involving two million children4748, reported negligible weight gain following deworming. In addition, meta-analyses of multiple studies of deworming have failed to demonstrate consistent benefit of deworming on anthropometric and cognitive outcomes3234.

Water, hygiene and sanitation (WASH) interventions

Only four trials involving WASH interventions for STH have been reported from India since 1995. These studies were carried out in Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa. Two of these were based on association with the ‘Total Sanitation Campaign’ initiated by the Indian government, which included the provision of flush pit latrines and community mobilization in village populations in whom parasitological measures of STH were recorded5153. Clasen et al51 did not observe any difference in the prevalence of STH between the intervention arm (16.00%) and the control arm (16.40%). There were also no significant differences in the prevalence of Ascaris (0.70 and 0.30%), hookworm (14.10 and 15.60%) or Trichuris (2.60 and 0.60%) between the two arms. Patil et al53 had similar findings with no significant difference in the prevalence of Ascaris between the intervention arm (4.30%) and control arm (4.40%). Other outcomes assessed were anaemia and weight gain. None of the studies found a significant difference in the weight-for-age Z scores between the two trial arms4950515253 while one study which measured levels of anaemia did not find a significant difference in anaemia between the two arms post-intervention53. All four studies showed benefit in terms of the intervention being adopted in the households4950515253. One study showed coverage of 60 per cent by residual chlorine in the households of the intervention arm50 and another study showed increased latrine coverage in the villages of intervention arms, although there was clear resistance to the adoption and usage51. Patil et al53 also demonstrated a reduction in open defecation in adult men (9.50%, P=0.001), adult women (10.00%, P<0.001) and under-five children (5.00%, P=0.014). Although there was some evidence of behavioural change following the intervention, no effect on STH and other clinically relevant outcomes was seen. However, studies conducted in other settings have reported benefits. A meta-analysis by Strunz et al66 found a significant decrease in STH infections associated with sanitation and hygiene interventions. They found that access to treated water decreased the odds of infection with Ascaris [odds ratio (OR)-0.40, 95% CI: 0.39-0.41] and Trichuris (OR 0.57, 95% CI: 0.45-0.72) and similarly so did availability of sanitation facilities. Usage of footwear decreased the risk of hookworm infection (OR 0.29, 95% CI: 0.18-0.47%). Hand hygiene and usage of soap were also associated with lower rates of infection with STH overall (OR 0.47, 95% CI: 0.24-0.90 and 0.53, 0.29-0.98, respectively)66.

Recently, two large studies on WASH interventions for the prevention of diarrhoea and stunting, the WASH Benefits Study (in Kenya and Bangladesh) and the Sanitation, Hygiene, Infant Nutrition Efficacy (SHINE) Study in Zimbabwe have been carried out. The WASH Benefits Study includes two cluster RCTs to assess the impact of WASH interventions to infants in Kenya and Bangladesh which were conducted between 2012 and 20146768. In both these sites, WASH interventions alone, which included improvement of latrines, provision of handwashing stations and promotion of behavioural change, did not show any significant positive outcomes with relation to decrease in the prevalence of diarrhoea or increase in linear growth6768. The SHINE Study, undertaken in two rural districts of Zimbabwe, was a cluster-randomized community-based study that aimed to determine the combined and independent effects of a WASH intervention and improved nutrition in 18-month old babies as measured by anaemia and linear growth69. Findings from this trial (unpublished) also indicate that WASH interventions did not independently improve growth outcomes or reduce the prevalence of diarrhoea70. Overall, the ‘sanitary awakening’71, even if achieved, does not seem to ensure success with regard to positive disease outcomes and mortality in developing nations. However, it is important to note that the outcomes in these studies were not measured uniformly, and a longer follow up period might be required.

Conclusions

Intervention studies of preventive chemotherapy with albendazole in India have demonstrated significant reductions in STH prevalence following treatment. However, despite reports of high coverage, none of the studies demonstrated a post-intervention prevalence of STH infection less than 15 per cent, suggesting that ongoing transmission is likely to continue to occur. These studies were done largely in SAC and reported secondary outcomes including effects of deworming on weight gain, anaemia, cognition and growth. These studies did not demonstrate consistently significant differences in these outcomes although a few showed a significant weight gain in children following deworming. The inability to sustain very low levels of prevalence, due to rapid reinfection, could explain the lack of appreciable changes in the secondary outcomes in these studies. Some of the impact assessment studies done in India have also observed the pattern of lowering of the prevalence of STH infection followed by reinfection, post-community deworming. The untreated individuals in these communities might be contributing to this rapid reinfection rate.

It appears that the current strategy of reducing morbidity by providing routine MDA to SAC and PSAC will need to continue for the foreseeable future in many areas of India given the inability of the current strategy to interrupt transmission. This strategy may not be sustainable in the long term due to the economic costs involved in running such a large public health programme. In addition to the findings following deworming, WASH interventions did not prove to be effective in reducing STH prevalence or in attenuating other secondary outcomes in most of the reported studies done in India. The lack of consistent and demonstrable benefit with WASH interventions suggests that interventions with much higher coverage, quality and fidelity are needed, in addition to improved WASH behaviour to sustain usage and eventually influence health outcomes.

Given the need for long-term investments in morbidity control programmes and WASH infrastructure, it may be valuable to explore other strategies to interrupt transmission of STH in India. These strategies could include community-wide MDA at increased frequency to attempt to reduce reinfection and reach the elimination threshold within communities. The DeWorm3 project is a large multi-country set of cluster-randomized trials being conducted in Benin, Malawi and India to determine the feasibility of such an approach in interrupting STH transmission72. In addition, WASH interventions need further development and evaluation to optimize their impact in the Indian context and programmes aimed at behavioural modification may need to be locally adapted to be acceptable to communities, as a ‘one size fits all’ strategy may not work in a diverse country like India.

Maximizing the value of public resources to improve healthcare in India requires careful consideration of strategies for the control and possible elimination of disease. STH infections are prevalent in India, and alternative approaches to interrupt transmission may be highly cost-effective in many settings.

Financial support & sponsorship: The authors acknowledge the support of the DeWorm3 project funded through a grant to the Natural History Museum, London, UK from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1129535, PI JLW).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Helminth infections: Soil-transmitted helminth infections and schistosomiasis. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11748/

- [Google Scholar]

- Soil-transmitted helminth infections: Updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:547-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investing to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: Third WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2015. p. :191.

- 2017. Neglected tropical diseases: PCT Databank. Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/preventive_chemotherapy/sth/en/

- Global numbers of infection and disease burden of soil transmitted helminth infections in 2010. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical distribution of soil transmitted helminths and the effects of community type in South Asia and South East Asia - A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197-223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antenatal anthelmintic treatment, birthweight, and infant survival in rural Nepal. Lancet. 2004;364:981-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasmodium/intestinal helminth co-infections among pregnant Nigerian women. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:1055-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship of childhood protein-energy malnutrition and parasite infections in an urban African setting. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:374-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal parasites, growth and physical fitness of schoolchildren in poor neighbourhoods of Port Elizabeth, South Africa: A cross-sectional survey. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:488.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of hookworm infection and deworming on anaemia in non-pregnant populations: A systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:776-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soil-transmitted helminth infections: Ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and distribution of soil-transmitted helminth infections in India. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and clustering of soil-transmitted helminth infections in a tribal area in Southern India. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:1452-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overview of intestinal parasitic prevalence in rural and urban population in Lucknow, North India. J Commun Dis. 2007;39:217-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence, intensities and risk factors associated with geohelminth infection in tea-growing communities of Assam, India. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:688-701.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminths in Bihar state, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003790.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections among primary school children, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2015. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal parasitic infections and demographic status of school children in Bhopal region of Central India. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9:83-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2013. GiveWell. Prevalence of Soil Transmitted Helminths in the State of Rajasthan. Summary Report prepared by ‘Deworm the World Initiative’. Available from: http://files.givewell.org/files/DWDA%202009/DtWI/DtWI%20Rajasthan%202013%20prevalence%20survey%20report.pdf

- GiveWell. Report on Prevalence and Intensity of Soil Transmitted Helminth Infections in Chattisgarh. Available from: http://files.givewell.org/files/DWDA%202009/DtWI/Deworm_the_World_Chhattisgarh_prevalence_survey_report_August_2016.pdf

- Prevalence & risk factors for soil transmitted helminth infection among school children in South India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:76-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. Preventive chemotherapy to control soil-transmitted helminth infections in at-risk population groups: Guideline. Geneva: WHO; Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/deworming/en/

- Assessment of the anthelmintic efficacy of albendazole in school children in seven countries where soil-transmitted helminths are endemic. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e948.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Deworming Day | National Health Portal of India. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/National-Deworming-Day_pg

- Deworming drugs for soil-transmitted intestinal worms in children: Effects on nutritional indicators, haemoglobin and school performance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD000371.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2016. Does mass deworming affect child nutrition? Meta-analysis, cost-effectiveness, and statistical power. USA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Report No.: 22382 Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w22382

- Mass deworming to improve developmental health and wellbeing of children in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e40-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of periodic deworming on nutritional status of ascaris-infested preschool children receiving supplementary food. Lancet. 1977;2:108-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soil-transmitted helminth reinfection after drug treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological surveys of, and research on, soil-transmitted helminths in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:31.

- [Google Scholar]

- London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases. Uniting to Combat NTDs. Available from: http://www.unitingtocombatntds.org/london-declaration-neglected-tropical-diseases/

- Soil-transmitted helminth eggs are present in soil at multiple locations within households in rural Kenya. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0157780.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detecting and enumerating soil-transmitted helminth eggs in soil: New method development and results from field testing in Kenya and Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005522.

- [Google Scholar]

- WASH practices - A determinant of gastrointestinal community health: A community study from rural Odisha, India. J Gastrointest Dig Syst. 2017;7:490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health and environmental sanitation in India: Issues for prioritizing control strategies. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2011;15:93-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of albendazole in improving nutritional status of pre-school children in urban slums. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37:19-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Six-monthly de-worming in infants to study effects on growth. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:823-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Periodic deworming with albendazole and its impact on growth status and diarrhoeal incidence among children in an urban slum of India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:261-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of deworming on malnourished preschool children in India: An open-labelled, cluster-randomized trial. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e223.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population deworming every 6 months with albendazole in 1 million pre-school children in North India: DEVTA, a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1478-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the impact of a school-based safe water intervention on household adoption of point-of-use water treatment practices in Southern India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:370-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of household-based drinking water chlorination on diarrhoea among children under five in Orissa, India: A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India: A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e645-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of improved rural sanitation on diarrhoea and helminth infection: Design of a cluster-randomized trial in Orissa, India. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2012;9:7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of India's total sanitation campaign on defecation behaviors and child health in rural Madhya Pradesh: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001709.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative assessment of Ascaris lumbricoides infection in school children from a slum in Visakhapatnam, South India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30:572-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of co-administration of albendazole and diethylcarbamazine against geohelminthiases: A study from South India. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:541-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability of soil-transmitted helminth control following a single-dose co-administration of albendazole and diethylcarbamazine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:355-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of two annual, single-dose mass drug administrations of diethylcarbamazine alone or in combination with albendazole on soil-transmitted helminthiasis in filariasis elimination programme. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9:1030-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact on prevalence of intestinal helminth infection in school children administered with seven annual rounds of diethyl carbamazine (DEC) with albendazole. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:330-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential effect of mass deworming and targeted deworming for soil-transmitted helminth control in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2017;389:287-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should the goal for the treatment of soil transmitted helminth (STH) infections be changed from morbidity control in children to community-wide transmission elimination? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003897.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the interruption of the transmission of human helminths with mass drug administration alone: Optimizing the design of cluster randomized trials. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect on weight gain of routinely giving albendazole to preschool children during child health days in Uganda: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333:122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of deworming on nutritional status of ascaris infested slum children of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Indian Pediatr. 2002;39:1021-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploiting Externalities to Estimate the Long-Term Effects of Early Childhood Deworming. (Policy Research Working Papers 7052). The World Bank. 2014. Available from: http://www.elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/1813-9450-7052

- [Google Scholar]

- Worms: Identifying impacts on education and health in the presence of treatment externalities. Econometrica. 2004;72:159-217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001620.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Kenya: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e316-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of water quality, sanitation, handwashing, and nutritional interventions on diarrhoea and child growth in rural Bangladesh: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e302-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- The sanitation hygiene infant nutrition efficacy (SHINE) trial: Rationale, design, and methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 7):S685-702.

- [Google Scholar]

- WASH and Nutrition Interventions for Child Growth and Development: Results from the WASH-Benefits and SHINE Trials Webinar Presented at: WASH and Nutrition Interventions for Child Growth and Development: Results from the WASH-Benefits and SHINE Trials. 2018. Available from: https://coregrouporg/event/wash-and-nutrition-interventions-for-child-growth-and-development-results-from-the-wash-benefits-and-shine-trials/

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the feasibility of interrupting the transmission of soil-transmitted helminths through mass drug administration: The deWorm3 cluster randomized trial protocol. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006166.

- [Google Scholar]