Translate this page into:

Evaluation of vaginal pH for detection of bacterial vaginosis

Reprint requests: Dr R. Hemalatha, Scientist “E”, National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR), Jamai Osmania (PO), Hyderabad 500 604, India e-mail: rhemalathanin@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is highly prevalent among women in reproductive age group. Little information exists on routine vaginal pH measurement in women with BV. We undertook this study to assess the utility of vaginal pH determination for initial evaluation of bacterial vaginosis.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study vaginal swabs were collected from women with complaints of white discharge, back ache and pain abdomen attending a government hospital and a community health clinic, and subjected to vaginal pH determination, Gram stain, wet mount and whiff test. Nugent score and Amsel criteria were used for BV confirmation.

Results:

Of the 270 women included in the analysis, 154 had BV based on Nugents’ score. The mean vaginal pH in women with BV measured by pH strips and pH glove was 5 and 4.9, respectively. The vaginal pH was significantly higher in women with BV. Vaginal discharge was prevalent in 84.8 per cent women, however, only 56.8 per cent of these actually had BV by Nugent score (NS). Presence of clue cells and positive whiff test were significant for BV. Vaginal pH >4.5 by pH strips and pH Glove had a sensitivity of 72 and 79 per cent and specificity of 60 and 53 per cent, respectively to detect BV. Among the combination criteria, clue cells and glove pH >4.5 had highest sensitivity and specificity to detect BV.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Vaginal pH determination is relatively sensitive, but less specific in detecting women with BV. Inclusion of whiff test along with pH test reduced the sensitivity, but improved specificity. Both, the pH strip and pH glove are equally suitable for screening women with BV on outpatient basis.

Keywords

Amsel criteria

bacterial vaginosis

Nugent score

pH test

whiff test

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common vaginal infections among women in reproductive age. It is a condition of vaginal flora imbalance, in which the typically plentiful H2O2 producing lactobacilli are scarce and other bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum and anaerobes (e.g. Prevotella, Mobiluncus, Bacteroides) are overly abundant12.

BV has been linked to low birth weight infants, preterm delivery, chorioamnionitis, post hysterectomy cuff cellulitis, post surgical endometritis, endometritis following vaginal delivery, and pelvic inflammatory disease345678. Women with BV are at higher risk of infection with human papilloma virus (HPV), Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), Trichomonas vaginalis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and HIV91011. We have recently shown an association between high vaginal pH and cervicovaginal inflammatory cytokines12, that are implicated in increased vulnerability to HIV, sexually transmitted infection (STI) and preterm delivery, in asymptomatic women with BV13. Given the high prevalence and gravity of associated morbidity, it is critical to diagnose and treat women, particularly pregnant women affected by BV appropriately. Conventional diagnostic methods for BV include the methods of Amsel et al14 and Nugent et al15. An easy, rapid and inexpensive self-diagnostic test for BV may help to minimize the tendency to self-treat symptomatic BV blindly with antibiotics or treating inappropriately. Assessment of intravaginal pH is a helpful, but frequently neglected procedure that can be used to evaluate vaginal health16. This study was conducted to assess the utility of vaginal pH determination to be used as a tool by women for self-detection of BV.

Material & Methods

Study population: In this cross-sectional study 464 non pregnant women were enrolled from Gynaecological outpatient clinics of Government Maternity Hospital (GMH) and Addagutta Community Health Clinic located at Hyderabad, India, during October 2008 and October 2009. These women visited the hospital for complaints such as white discharge, pain abdomen and back ache. Informed written consent was obtained from all women. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of National Institute of Nutrition (NIN), Hyderabad. Women with history of gynaecological cancer, who had bleeding during the examination, used antibiotics/vaginal medication during the previous three weeks and those who had sexual intercourse in the last two days were excluded from the study. Of the 464 women screened (284 from GMH and 180 from Addagutta Clinic), 330 women fulfilled the eligibility criteria from whom demographic and clinical data were collected using a structured questionnaire. Height and weight were measured to calculate BMI (weight in kg/height in m2). General and gynaecological examinations were done to evaluate reproductive health. With 30 per cent prevalence of BV and assuming 70 per cent sensitivity of vaginal pH in detecting BV12, with a precision of 10 per cent, sample size was arrived at 270 with 80 per cent power and significance at 5 per cent.

Sample collection: Vaginal swabs were collected for vaginal pH measurement, Gram stain, wet mount, and whiff test. Vaginal pH was evaluated immediately with the pH strips and vaginal pH glove simultaneously. Samples for Gram stain were collected and a smear was performed. Gram staining and Nugent scoring were done after transporting the smears to the laboratory at NIN with microscope facility (within 2 to 3 h after sample collection). The pH of secretions collected from the lateral vaginal wall was measured using a coloured indicator ranging from 3.5 - 5.2. Secretions collected with other cotton tip applicator from the lateral wall were smeared on to a glass slide for Nugent Gram stain evaluation. Vaginal smear white blood cells (WBC) were counted per field. The presence of Trichomonas was checked by microscopy.

Criteria for diagnosing BV: Nugent method15 was used to diagnose BV. A Nugent Score (NS) of 7-10 is classified as BV; 4-6 as intermediate flora and 0-3 as normal. The clinical criteria reported by Amsel et al14 for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis were also evaluated: thin homogeneous discharge, vaginal pH greater than 4.5, positive whiff test or release of amine odour after addition of 10 per cent KOH, and clue cells on microscopic evaluation. The presence of any three of the four Amsel criteria confirms BV.

Quality control: Quality control assessment was done for glove as well as pH paper with a bench top pH meter (thermo-Orion 3 star, USA), which has a fine electrode, meant specifically to measure small quantities of fluids. Reproducibility was checked once in every two weeks.

Statistical analysis: Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic and clinical variables. Patient characteristics were compared between women with and those without bacterial vaginosis by using the Student t test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data and Chi-square test for non parametric categorical data. Specificity, sensitivity, area under curve (AUC) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each of the individual criterion, combinations of the criteria were calculated considering NS 7-10 as BV.

Results

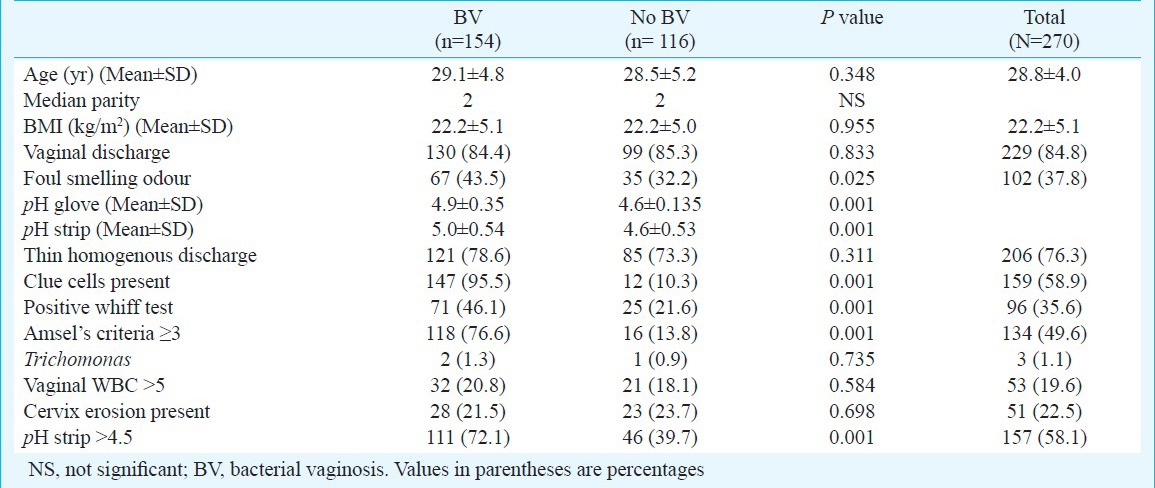

After a Gram stain and microscopic examination of samples obtained from 330 women, those with intermediate flora and Candida infection were excluded and the final analysis was done on 270 samples. Of the 270 women, 154 were diagnosed with BV and 116 had normal vaginal flora based on Nugents’ score. The mean age (in years) and body mass index (BMI in kg/m2) of the subjects were 28.8 and 22.2, respectively. The median parity of the subjects was two. A proportion of 33.3 per cent women was illiterate and 17.8 per cent had primary education. Illiterate women and women with only primary education had parity more than two compared to women with higher education (P<0.05). Majority (79.6%) of the women had adopted tubectomy as a sterilization method.

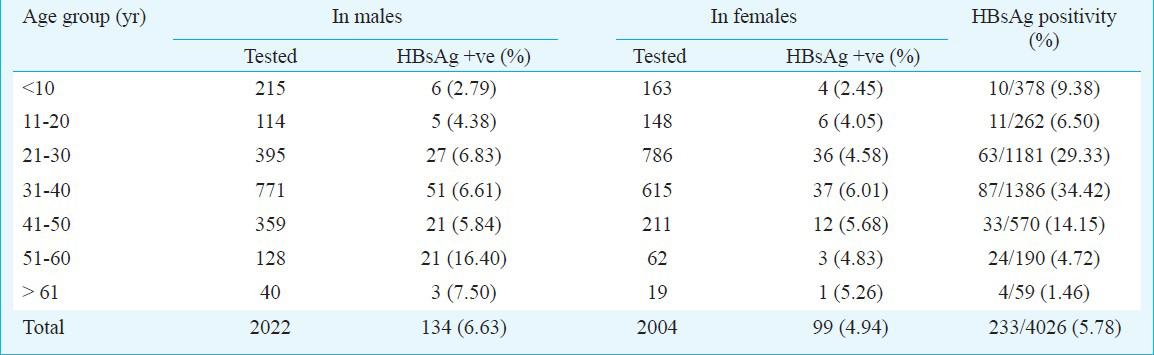

The demographic and clinical variables of women are given in Table I. Between the groups the factors such as age, BMI and parity had no statistically significant difference. Vaginal discharge was the symptom in 84.8 per cent of the subjects with BV and 85.3 per cent with no BV. Foul smell was the symptom in 43.5 per cent of the subjects with BV. Women with BV were more likely to have foul smell as symptom (P<0.002) compared to normal subjects. On gynaecological examination, 22.5 per cent of the women had cervical erosion. Cervical erosion incidence was similar in women with and without BV. However, women with cervical erosion had more frequent abnormal vaginal discharge or thin homogenous discharge on examination (P<0.0001) compared to women with healthy cervix. Similarly, laboratory diagnosed vaginal white blood cells by microscopy was more frequent (P<0.05) in women with cervical erosion compared to women with healthy cervix.

Overall, 58.1 (157) and 65.2 (176) per cent women had vaginal pH >4.5, when measured with pH strips and pH glove respectively. The mean vaginal pH in women with BV measured by pH strips and pH glove was 5 and 4.9, respectively, and the difference in vaginal pH between BV and normal women was significant (P<0.001) (Table I). Presence of clue cells and positive whiff test were significant (P<0.001) for BV. As expected, Amsel's criteria were significant (P<0.001) for BV (Table I). Women with vaginal WBC >5 had vaginal pH > 4.5 (P=0.002). In the present study 3 (1.1%) women were infected with Trichomonas, but there was no significant difference between the groups.

The sensitivity, specificity, AUC, 95% CIs of the individual criterion and combination of criteria for diagnosing BV, when compared with Nugent score are shown in Table II. Clue cell was the criterion with highest sensitivity (95%) and specificity (90%) among the individual criteria. Vaginal pH >4.5 detected by pH strips and pH glove had a sensitivity of 72 and 79 per cent, and a specificity of 60 and 53 per cent, respectively (Table II). Amsel's criteria had 77 and 86 per cent sensitivity and specificity, respectively. Among the combination criteria, clue cells and glove pH >4.5 had highest sensitivity and specificity. pH test when combined with positive amine (whiff) test had 40 per cent and about 75 per cent sensitivity and specificity, respectively. Thin homogenous discharge had the lowest specificity (27%). The positive predictive values (PPV) of pH strip (pH>4.5) was 71 per cent (confidence interval: 0.63-0.78) and the negative predictive values (NPV) was 62 per cent (confidence interval: 0.52-0.71) when compared with Nugent score.

Discussion

Vaginal pH of more than 4.5 was less than 80 per cent sensitive in diagnosing BV, that may be accurate only 60 per cent of the time. Inclusion of whiff test along with pH test further reduced the sensitivity, but improved specificity. The difference in mean pH measurement between the two methods (pH glove and pH strip) was not significant.

Reproductive tract infections continue to cause considerable morbidity among women. Our results confirmed the findings that women with bacterial vaginosis were more likely to have vaginal symptoms, specifically foul odour in comparison to healthy women. In resource-poor settings, the World Health Organization (WHO) syndromic management protocol for vaginal discharge is most commonly used to diagnose vaginal infections. It is based on clinical assessment with speculum examination only16. Though, this protocol is found to be effective in management of abnormal vaginal discharge17, it is well known that cervical erosion can be associated with excessive non-purulent vaginal discharge due to the increased surface area of columnar epithelium containing mucus-secreting glands. The results of the present study confirmed that women with cervical erosion had vaginal discharge as symptom in comparison to women with healthy cervix.

In a study by Posner et al18, evaluation of pH plus amine (whiff) test was better than syndromic management protocols and easiest to implement in resource-poor settings. Our results also confirm the same. In the present study 84.8 per cent women presented with abnormal vaginal discharge, but only 56.8 per cent of them were positive for BV. The sensitivity and specificity of Amsel criteria in our study were better than that reported by Posner et al18 and roughly similar to that obtained by Schwebke et al19. Our results demonstrated that clue cells were the most reliable single indicator for BV as reported previously20, however, identification of clue cells requires on-site microscopy facility, trained personnel and time.

Though the sensitivity of vaginal pH in detecting BV was considerably lesser, the specificity was much higher in the current study compared to an earlier study21. False elevations in pH can be encountered when semen and mucus were sampled, exclusion of women who had coitus in the previous two days might have contributed to improved specificity and exclusion of women with Candida infection to improved negative predictive value in the present study. However, exclusion of women with intermediate flora, which is not practical, might have falsely contributed to better specificity. Contrary to our study, pH and whiff test together had a high sensitivity and specificity in a study by Thulkar et al21. Whiff test seems less practical and requires a good sense of smell22. However, inclusion of whiff test along with pH test improves specificity. A study in a population with low prevalence of BV showed correlation of high vaginal pH with BV and suggested vaginal pH as a simple tool for the diagnosis of BV23.

Self-sampling the vagina seems to be acceptable to women of multiple ethnic groups24. Self-sampling of vaginal pH seems suitable for implementation before using over the counter products for presumed vaginitis25. Moreover, a better informed self-diagnosis would ultimately reduce delayed treatment and possible secondary complications. A major limitation of the study was exclusion of women with intermediate flora that might have contributed to better sensitivity and specificity of the pH test.

In conclusion, our findings show that vaginal pH determination is relatively sensitive, but less specific in detecting women with BV. Inclusion of whiff test along with pH test may reduce the sensitivity, but improves specificity. Both pH glove and pH strip are equally suitable for screening women with BV on outpatient basis. Further studies are required to explore the possibility of self-evaluation of vaginal pH with pH glove at community level.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Director of the National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India for providing the facilities and support system, and Ms. Bhavani (nurse) and Shri D. Madhusudan Rao (technician), for clinical and technical support. The authors acknowledge CD Pharma India Pvt. Ltd., for financial support. This study would not have been possible without the co-operation of the women who were subjects of the study and we are grateful to them.

References

- World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted and other reproductive tract infections. Geneva: WHO; 2005. p. :11-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Few microorganisms associated with bacterial vaginosis may constitute the pathologic core: a population-based microbiologic study among 3596 pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;178:580-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low birth-weight infant. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case-control study of chorioamnionic infection and histologic chorioamnionitis in prematurity. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:972-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis vaginitis are risk factors for cuff cellulitis after abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1016-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for post-cesarean endometritis. Obstet Gynecl. 1990;75:52-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical and microbiologic analysis of risk factors for puerperal endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:402-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for upper genital tract infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1184-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial vaginosis is associated with uterine cervical human papillomavirus infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between acquisition of Herpes simplex virustype 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;18:1863-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervicovaginal inflammatory cytokines and sphingomyelinase in women with and without bacterial vaginosis. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344:35-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vaginal pH neutralization by semen as a cofactor of HIV transmission. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:19-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improving by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila. 1997. Syndromic case management of STD. Available from: http;//www.wpro.who.int/…/Advocacy-Brochure- on-Syndromic-Case-Mgt-of-STD.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of two clinical protocols for the management of woman with vaginal discharge in Southern Thailand. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:194-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis in a resource-poor setting. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:52-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity of the vaginal gram stain for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:573-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statistical evaluation of diagnostic criteria for bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:155-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of pH test & Whiff test in syndromic approach of abnormal vaginal discharge. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:445-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experience with routine vaginal pH testing in a family practice setting. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2004;12:63-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of vaginal pH in diagnosis of infections and its association with reproductive manifestations. J Clin Lab Anal. 2008;22:375-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes to self-sampling for HPV among Indian, Pakistani, African, African-Caribbean and white British women in Manchester, UK. J Med Screen. 2004;11:85-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variability of vaginal pH determination by patients and clinicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:368-73.

- [Google Scholar]