Translate this page into:

Current status of lupus nephritis

Reprint requests: Dr Ajay Jaryal, Department of Nephrology, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla 171 001, Himachal Pradesh, India e-mail: drajayjaryal@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic disease of unknown aetiology with variable course and prognosis. Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the important disease manifestations of SLE with considerable influence on patient outcomes. Immunosuppression therapy has made it possible to control the disease with improved life expectancy and quality of life. In the last few decades, various studies across the globe have clarified the role, dose and duration of immunosuppression currently in use and also provided evidence for new agents such as mycophenolate mofetil, calcineurin inhibitors and rituximab. However, there is still a need to develop new and specific therapy with less adverse effects. In this review, the current evidence of the treatment of LN and its evolution, and new classification criteria for SLE have been discussed. Also, rationale for low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide as induction agent followed by azathioprine as maintenance agent has been provided with emphasis on individualized and holistic approach.

Keywords

Autoimmune disorder

immunosuppressive therapy

lupus nephritis

systemic lupus erythematosus

treatment

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, debilitating autoimmune disorder that involves multiple organ systems either simultaneously or sequentially with relapsing and remitting course. The word lupus is a Latin term which means wolf. 'Lupus' has been used since the middle ages by the Romans to describe the ulcerative lesions of the skin in lupus patients, which resemble to those caused by a wolf bite. William Osler first described nephritis as a component of SLE1. Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of the common complications in patients with SLE and influences overall outcome of these patients. About two-thirds of patients with SLE have renal disease at some stage which is a leading cause of mortality in these patients2. Manifestations of LN vary from asymptomatic urinary abnormalities to rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted worldwide which have added evidence to therapeutic armamentarium with improved patient outcome and reduced drug toxicity. The low-dose intravenous (iv) cyclophosphamide (CYC) as induction agent followed by azathioprine (AZA) as maintenance therapy especially in less severe LN is outcome of studies conducted in Europe and India345. The equal outcomes with mycophenolate and CYC even in severe LN have broadened the choice for clinician in managing patients with severe LN6.

Classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus

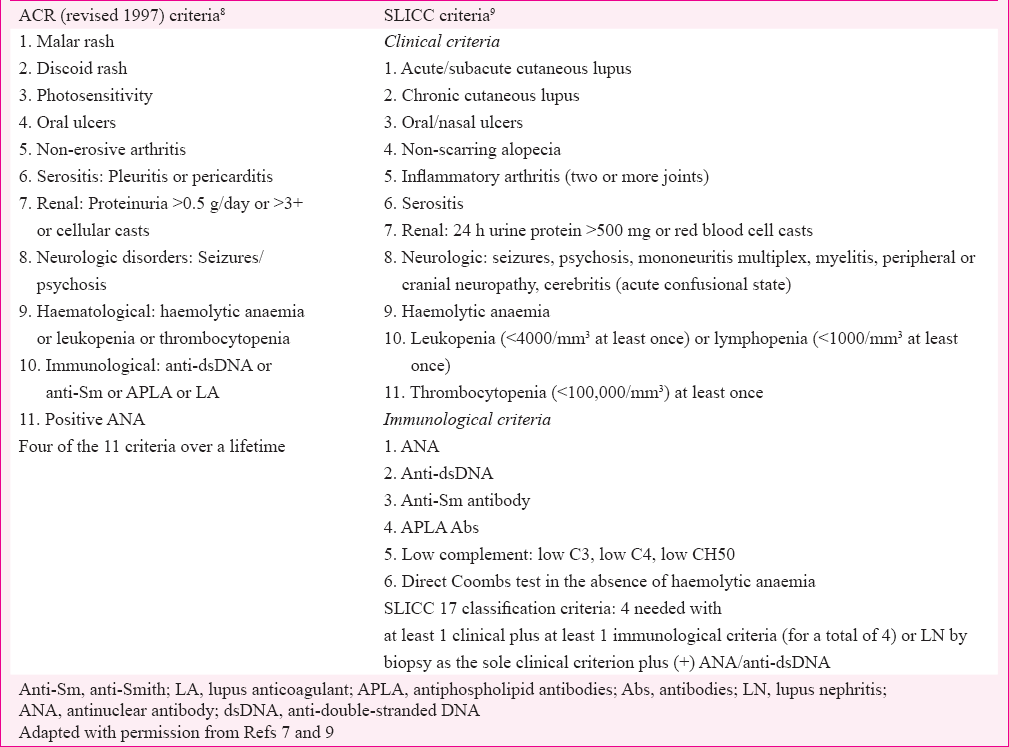

The diagnosis of SLE is clinically supported by serology and histopathology. In the absence of diagnostic criteria, clinicians use classification criteria proposed by various research organizations from time to time to appropriately manage these patients. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised classification criteria for SLE published in 19827 and subsequently revised in 19978 (Table I) have been in widespread use. Although in clinical use for over a decade, the 1997 criteria have not been validated unlike 19829 criteria and have a few shortcomings, such as duplication of terms for cutaneous lupus (malar rash and photosensitivity) and omission of other lupus manifestations such as myelitis and biopsy proven LN. To address these shortcomings, the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) (an international group of SLE researchers) developed and validated new classification criteria9. A total of 17 criteria were identified. The SLICC (Table 1) criteria for SLE classification requires (i) fulfilment of at least four criteria, with at least one clinical criterion and one immunologic criterion or (ii) the presence of LN with positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) or anti-double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies. In the validation set, the SLICC Classification criteria resulted in fewer misclassifications and had greater sensitivity but less specificity9. Amezcua-Guerra et al10 compared 1997 ACR and 2012 SLICC criteria and found their performance similar in uncontrolled life scenario.

Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis

The pathogenesis of SLE and LN is a result of interplay of multiple factors, notably genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors. It is characterized by loss of self-tolerance which leads to polyclonal antibody activation classically manifesting as positive ANA and full-house pattern on immunofluorescence in renal biopsy specimen1112. In the early stage of disease, innate immune system activates T-cells and activators of B-cells which all lead to activation of adaptive immune response11. T-cells including type 1 T-helper (TH1) cells and TH17 drive the systemic and intra-renal activation of B-cells1314. B-cells after activation by either T-cells or innate immune system generate various autoantibodies and cytokines15. More than 10 genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted so far in multiple ethnicities to identify genetic loci linked with SLE have collectively identified >50 genes associated with SLE. It also includes patients with LN16. Some of these genes breach immune tolerance and produce autoantibodies such as anti-dsDNA, which might act along with genes that augment innate immune signalling to generate effector leucocytes and release of inflammatory mediators and other autoantibodies that together initiate renal assault1718. The genes implicated in genesis of LN include B lymphoid tyrosine kinase (BLK), human leucocyte antigen-antigen D related (HLA-DR), Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 4(STAT4) and toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)1819.

Lupus nephritis definition and classification

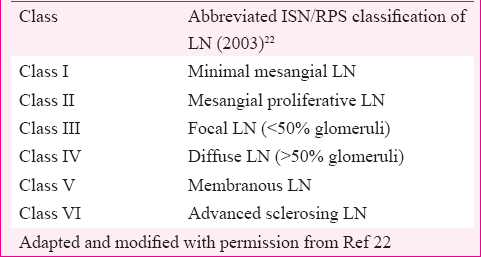

The ACR lupus classification criteria define LN by proteinuria >0.5 g/day or a urinary protein/creatinine ratio (UPCR) of >0.5 or urinary protein greater than 3+ by dipstick analysis or urinary cellular casts of more than five cells per high-power field (in the absence of urinary tract infection)8. The term LN encompasses diverse patterns of renal injury encountered in patients of SLE, through immune-mediated mechanism20. Besides an immune complex-mediated glomerular disease, most patients often have tubulointerstitial and vascular changes such as fibrinoid necrosis and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA)21. The World Health Organization (WHO) in 1974 gave classification of LN based entirely on glomerular lesions, and subsequently, it underwent repeated transformations till we had the most accepted classification given by the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the Renal Pathology Society (RPS)2022. The most significant outcome of ISN/RPS classification was high inter and intra-observer reproducibility with flipside being its failure to give adequate representation to extraglomerular lupus lesions. The extraglomerular lesions of LN are caused by immune- and non-immune-mediated mechanisms and significantly influence disease outcome. Lupus podocytopathy is a recently described entity, seen in the subset of patients of lupus presenting with nephrotic syndrome, with kidney biopsy showing only mild mesangial expansion without peripheral capillary wall immune deposits. The pathophysiology of nephrotic syndrome here is based on fusion of foot processes of glomerular visceral epithelial cells as seen in minimal change disease (MCD). In a large cohort study of 3750 kidney biopsies of LN patients, lupus podocytopathy was found in 1.33 per cent biopsies23.

Role of kidney biopsy in lupus nephritis

Despite the presence of clinical criteria, LN remains a histopathological diagnosis. The kidney biopsy provides an unequivocal diagnosis of LN. It provides evidence for disease prognosis, activity, chronicity and planning of therapy. As the therapy of LN consists of potentially toxic drugs, it may be harmful to venture into the treatment without definitive diagnosis. A given patient of SLE with features suggestive of renal involvement may have extraglomerular features of SLE such as TMA or non-lupus renal disease or drug-induced interstitial nephritis all with different management and outcomes. Hence, kidney biopsy is considered sine qua non in the management of LN. The usual indications for performing the first kidney biopsy are proteinuria >500 mg/day, active urine sediment (≥5 red blood cells or white blood cells per high-power field, mostly dysmorphic without evidence of infection) or rising serum creatinine242526. The current approach to treating LN and studying new therapeutic modalities is largely guided by ISN/RPS, classification (Table II).

Drugs used in treatment of lupus nephritis

The era of high-dose cyclophosphamide (CYC)

The treatment of LN consists of two phases - induction and maintenance. Induction therapy refers to the initial therapeutic regimen given in an attempt to produce remission of active disease. An aim during induction is to achieve rapid resolution of ongoing organ damage. The induction phase is followed by maintenance phase to sustain remission over a long period of time and to prevent disease flare. LN is associated with adverse outcomes without treatment, but with the present form of therapy, even partial disease remission improves patient and renal survival significantly at 10 years2728. Corticosteroids have been the mainstay of the treatment of LN. These are effective in controlling renal flares but alone did not improve long-term outcomes. The landmark studies done by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the role of CYC in maintaining long-term remission and preservation of renal function. The first NIH trial in198629 led to shift from oral to iv CYC and subsequently all the otherNIH trials3031 together established that the high-dose ivCYC was the only cytotoxic agent superior to steroids alone inLN and it became the ‘standard of care’. This success of high-dose CYC therapy came with the host of adverse events notably amenorrhoea, infertility, cytopenias and opportunistic infections such as herpes zoster31.

Azathioprine (AZA)

AZA is a purine analogue which inhibits DNA synthesis and acts most strongly on rapidly proliferating cells. It has been extensively used in organ transplant and various autoimmune diseases. As a result of pioneer NIH trials293031 where AZA performed inferior to iv CYC, it did not earn a place as induction therapy in LN. However, it emerged as a drug of choice as maintenance agent in LN being efficacious and safe to long-term iv CYC use. A few researchers have found oral AZA equally effective versus CYC in short-term (Dutch prospective study of 87 patients)32 as well as on long-term basis (retrospective cohort study of 26 patients)33. Although the response rates in the first two years in the Dutch study group were comparable, repeat renal biopsy samples from 39 patients showed a greater increase in chronicity index34. Subsequently, later follow ups (median 5.7 & 9.6 yr) showed more disease flares, more infections with higher rates of doubling of serum creatinine and death35. Besides these shortcomings, AZA is preferred as maintenance therapy, in pregnant patients and in patients intolerant to other first-line induction agents.

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) was introduced as a therapeutic option for LN in the beginning of 21st century3637. A large multiethnic induction trial on LN, in the US (>50% African Americans), randomized 140 patients with proliferative or membranous LN to iv CYC monthly pulses versus oral MMF up to 3 g daily, with a tapering dose of corticosteroids as induction therapy over six months. Although the study was powered as a non-inferiority trial, complete remissions and complete plus partial remissions at six months were significantly more common in the MMF arm (52%) than the CYC arm (30%) with better side effect profile, and at three years, there were no significant differences in the number of patients with renal failure, ESRD or mortality6. Similarly Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) involving 370 patients, randomized to receive either MMF (3 g/day) or monthly iv CYC pulse (0.5-1 g/m2) as induction therapy, showed no difference in rates of achieving complete and partial remission after six months of therapy (56.2% of patients receiving MMF vs. 53.0% of patients receiving iv CYC)38.

Low-dose cyclophosphamide (CYC)

During the same period, Euro-Lupus Group3 randomized 90 patients with proliferative LN, to receive either standard six monthly pulse of CYC (0.5-1 g/m2) followed by every third monthly infusions or to a shorter treatment course consisting of fixed dose of 500 mg iv CYC every two weeks for six doses (total dose, 3 g) and AZA maintenance therapy (2 mg/kg/day). The shorter regimen was equally efficacious, had less toxicity with significantly less severe and total infections, and follow up for 10 yr showed no differences in outcome between the treatment groups4. A pioneering Indian study (RCT) by Rathi et al5 involving 100 patients with less severe LN, equally divided to low-dose CYC (Euro lupus regimen) and MMF, found them to have comparable safety and efficacy outcomes over 24 wk.

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs)

With the experience from transplant medicine and proteinuric glomerular diseases, researchers used CNIs as induction39 and maintenance agent40 in proliferative and membranous LN41. CNIs have got dual mode of action viz., immunosuppression and stabilization of podocyte cytoskeleton42. Tacrolimus (TAC) has been found to be effective in proliferative, membranous as well as resistant LN and may have a role in pregnant patients43. A recently completed RCT with follow up of approximately five years found TAC non-inferior to MMF when combined with prednisolone, for induction therapy with AZA as maintenance albeit a non-significant trend of higher incidence of renal flares and loss of renal function44. Although effective in LN, CNI has been invariably associated with risk of relapse and always carries risk of nephrotoxicity with long-term use. Baoet al45 randomized 40 Chinese patients with Class V+IV refractory LN to receive either multitarget therapy (TAC+steroid+MMF) or iv CYC. At nine months, 65 per cent of patients in the multitarget group achieved complete remission compared with 15 per cent in the iv CYC group. Similar success of multitarget therapy has also been replicated by other researchers46. CNIs have narrow therapeutic index, and measurement of trough drug levels may be helpful in reducing nephrotoxicity. In a prospective Japanese study47 involving 19 patients, treated with corticosteroids and TAC, with or without mizoribine, TAC trough levels of 3.9±1.5 μg/l were found satisfactory in controlling LN. A retrospective Chinese study48 with the use of TAC for 46.0±37.9 months with target 12 h trough blood TAC level of 4-6 μg/l found it satisfactory for suppression of proteinuria. Hence, lower CNI trough levels may be effective in LN.

During earlier period, CYC was continued to be used even as maintenance therapy until Contreras et al49 compared outcome of using CYC, mycophenolate or AZA as maintenance agent after using cyclophosphamide as induction agent. They found use of MMF and AZA safe and efficacious versus CYC. Subsequently, there have been RCTs505152 with AZA, mycophenolate and meta-analysis5354 with both these agents as maintenance therapy, and both have been found to be equally efficacious and safe by most researchers barring MMF being more costlier but with advantage of the same agent being used as induction and maintenance therapy.

Biological agents in lupus nephritis

In the quest of using targeted therapy in SLE and LN, various biological agents have been investigated mainly in uncontrolled studies with the purpose of reducing toxicity and improving efficacy of non-specific immunosuppression in the current use. The various biological agents consisted of anti-B-cell therapies targeting either B-cell surface antigens (anti-CD20 and anti-CD22) or B-cell survival factors [anti-B lymphocyte stimulator/A proliferation-inducing ligand (anti-BLyS/APRIL) monoclonal antibodies], anti-cytokines antibodies (anti-interleukin-6) and novel drugs intervening in B-T cell co-stimulation [cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4-Ig)]55. The anti-B-cell-targeted therapies that have been investigated are rituximab (RTX)56 [chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (MAB)], ocrelizumab57 (humanized anti-CD20 MAB), epratuzumab58 (anti-CD 22 humanized MAB) and belimumab59 [Fully human anti-BlyS (B lymphocyte stimulator) MAB]. Other targeted therapies investigated included abatacept60 [(CTLA4-Ig) fusion protein] and atacicept61 (soluble fully human recombinant anti-APRIL fusion protein).

Rituximab (RTX)

RTX is a chimeric anti-CD20 MAB composed of the murine variable regions against CD20 and the human IgG Fc constant region. Rovin et al62 studied safety of RTX in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial in patients with LN treated concomitantly with MMF and corticosteroids. They found that although RTX depleted peripheral CD19 B-cells, anti-dsDNA titres and C3/C4 levels, but it did not transform into superior clinical outcomes. Further, it did not lead to any new safety issues. Besides dismal outcome in LUNAR trial, Weidenbusch et al63 in a systematic analysis found that RTX was able to induce complete or partial remission in 74 per cent of the patients who were refractory to current first-line drugs in severe LN.

Belimumab

Belimumab is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for the last 50 years in SLE. This was outcome of the clinical efficacy and safety demonstrated in two large-scale phase III RCTs, involving 1684 patients with lupus, conducted in people across various ethnicities and continents59. A pooled post hoc analysis of these trials at week 52, to evaluate the effect of belimumab on renal parameters in 267 patients with renal involvement at baseline without severe active LN, found improvement in various renal outcomes such as reduction in proteinuria, renal remission, renal flare and serologic activity in belimumab group, although the difference between the groups was not significant64.

Other drugs investigated in SLE and LN are as follows: Mizoribine (imidazole nucleoside inhibiting de novo purine synthesis) mainly in Japanese population where it did not offer any benefit when compared with steroid alone and has also been used with TAC6566. Leflunomide, an inhibitor of de novo pyrimidine synthesis, has been used mainly in non-renal SLE; however, it did not offer any advantages over other immunosuppression in the current use but was associated with host of adverse effects mainly thrombocytopenia, skin rash, diarrhoea and hepatotoxicity67. Use of leflunomide in LN was found to be equally efficacious and safe as CYC at least in short term68 and also in refractory LN69. However, at present, it does not fare better than current first-line immunosuppression in LN but has a role to play in refractory/resistant disease. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway has been implicated in genesis of malignancy and autoimmunity. Investigators used rapamycin an inhibitor of mTOR in murine model of LN, NZBW/F1 [F1 hybrid between the New Zealand Black (NZB) and New Zealand White (NZW) strains] female mice and found it effective in prolonging survival, maintaining normal renal function, normalizing proteinuria, restoring nephrin and podocin levels, reducing anti-dsDNA titres, ameliorating histological lesions and reducing mTOR glomerular expression activation70. Plasmapheresis acts by rapidly removing pathogenic antibodies and has been used as add-on therapy to baseline immunosuppression of mainly CYC and steroids, to improve outcome in LN. However, addition of plasmapheresis to current immunosuppression has not been found to improve outcomes in severe LN71. There are anecdotal reports of success of plasmapheresis in addition to current immunosuppression, but these are mainly in patients with associated diffuse alveolar haemorrhage or TMA72. Plasmapheresis can also be combined with iv immunoglobulin, especially in a setting where clinician is dealing with refractory LN73 or active life-threatening SLE and infection. There are uncontrolled studies on the use of intravenous immunoglobulin as initial therapy in LN usually along with steroids with equivocal outcomes albeit with steroid-sparing effect7475.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is an antimalarial drug with anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic and immunomodulatory properties. The use of HCQ has been associated with decreased probability of LN when used before onset of LN in SLE76 and also retards the onset of renal damage in patients with LN77. The use of HCQ has also been associated with increased probability of remission, reduced frequency of flares and improved survival7677. Angiotensin inhibitors/blockers [angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB)] are effective in reducing proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy and other proteinuric glomerular diseases. In a retrospective analysis, use of ACEI/ARB was found to be effective in reducing proteinuria and improving serum albumin7879. Their use was also associated with retarding the occurrence of renal involvement and reducing overall disease activity in SLE80. Stem cells have also been investigated as possible treatment for SLE, especially in severe form of the disease and LN both in mice81 and humans82. In one such study, the use of mesenchyme stem cells, in 10 patients with glomerulonephritis due to SLE, was associated with significant improvement in serum creatinine and creatinine clearance versus control population82. The exact mode of benefit of stem cells is not known, but it may be due to differentiation of these cells into renal cells or due to their anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antifibrotic, antiapoptotic, antioxidative, regenerative and paracrine effects83.

Evidence-based treatment for lupus nephritis

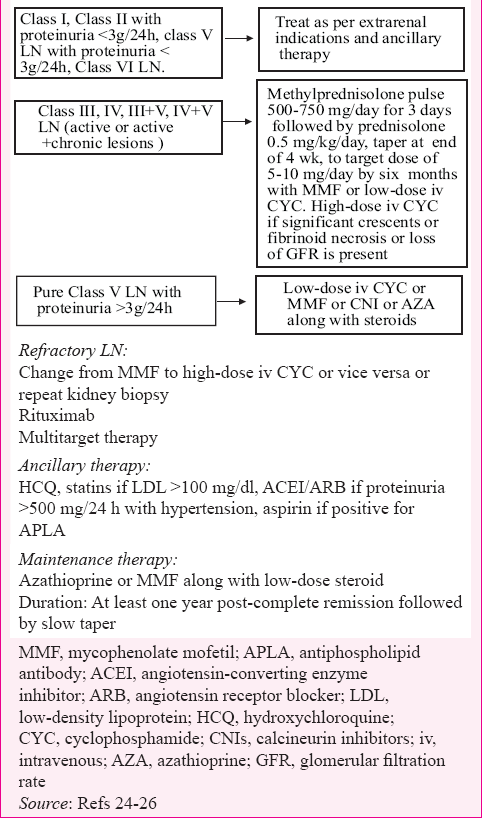

Guidelines developed by organizations such as the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcome (KDIGO), ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism and European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) are important and handy to use242526. Overall, immunosuppressive treatment should be guided by renal biopsy, and treatment aimed at complete renal response (proteinuria <0.5 g/24 h with normal or near normal renal function). According to ISN/RPS classification of LN22, Class I, Class II (with proteinuria <3 g/day) and Class VI LN do not need any treatment from renal point of view but should be treated as per extrarenal indications. All these major guidelines advise immunosuppression with either CYC or MMF combined with steroids in Class III/IV LN. ACR guidelines25 advocate to prefer MMF in Class III/IV LN, especially in African Americans and Hispanics. The KDIGO24 and EULAR26 guidelines advise dose target for MMF of 3 g/day, whereas ACR recommends 3 g/day for non-Asians and 2 g/day for Asians. Euro lupus regimen is recommended as alternate to MMF by EULAR/ERA-EDTA in severe LN, whereas ACR recommends Euro lupus regimen in patients of European descent. Both ACR and EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommend the use of steroids plus MMF in Class V LN with nephrotic range proteinuria whereas KDIGO recommends to choose any of CYC/MMF/AZA/CNI along with steroids in Class V LN. Steroids as per MCD are advised for the treatment of lupus podocytopathy, which has ultra-structural homology with MCD. There is evidence to use either of MMF or CYC in severe/crescentic LN, albeit with longer experience for later agent. The treatment of LN is summarized in Table III.

Refractory and relapsing lupus nephritis

Despite the use of aggressive immunosuppression, a few patients of LN may not respond. Around 20-70 per cent of patients with LN are reported to be resistant to first-line immunosuppressive therapy84. There is no uniformly accepted definition for resistant/refractory LN. According to EULAR/ERA-EDTA26, changing to an alternative drug is recommended for the patients who do not achieve partial response after 6-12 months, or complete response after two years of treatment. It is also suggested to switch to an alternative agent if there are signs of deterioration in the very early course of therapy. Such an alternative agent could be RTX alone or in combination with other immunosuppression or any one of the extended courses of CYC or CNI or plasmapheresis or multitarget therapy84. LN is a relapsing disease. Renal relapse/flare is defined by return of active urine sediment or proteinuria more than 0.5 g/day or worsening serum creatinine. The average rate of renal relapse after reduction or cessation of immunosuppression varies from 5 to 15/100 patient years, in different series within first five years of attaining remission85. Relapses should be treated with the same induction agent that was effective on previous occasion unless contraindicated (high dose CYC) and to consider repeat renal biopsy if there is uncertainty about diagnosis or chronicity of disease.

Treatment of LN should be continued up to one year after complete remission before tapering it off. According to KDIGO24, serial measurements of proteinuria and serum creatinine are most important biomarkers to monitor progress of LN, and resolution of proteinuria is most important predictor of kidney survival. Besides this, during each visit, patients should be regularly monitored for body weight, blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR), serum albumin, urinary sediment, serum C3 and C4, serum anti-dsDNA antibody levels and complete blood cell count. Patients should be initially followed up every 2-4 wk for 3-6 months and then every 3-6 months for the rest of life. Antiphospholipid antibodies and lipid profile should be measured at baseline and then periodically. Clinically lupus can either be in a chronic, quiescent or a relapse/flare. EULAR task force advises to use any of the available lupus disease indices such as the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group scale, the Safety of Estrogen in Lupus Erythematosus - National Assessment - SLEDAI, the European Consensus Lupus Activity Measure (ECLAM) or the Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM) to monitor lupus disease activity.

Ancillary treatment in lupus nephritis

According to KDIGO24 and EULAR/ERA-EDTA26, all patients with LN should receive HCQ unless contraindicated. According to EULAR/ERA-EDTA, all patients with LN should receive ACE/ARB if UPCR >50 mg/mmol or hypertensive, statins if low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) >100 mg/dl, acetyl-salicylic acid if positive for antiphospholipid antibodies, oral anticoagulant if antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLAS) or nephrotic syndrome with serum albumin <2 g/dl. Patients should also be vaccinated with non-live vaccine as appropriate for risk and age. They should also receive supplement of calcium and vitamin D with continuous vigil for metabolic bone disease. Patients with LN and TMA or diffuse alveolar haemorrhage should receive plasmapheresis. Sun exposure mainly ultraviolet light (UV) is a well-known factor leading to flare of cutaneous lupus; however, sun exposure has also been found to be associated with exacerbation of non-cutaneous lupus including LN in various anecdotal reports86. The proposed mechanism for such a phenomenon is increased breakdown of epidermal DNA by exposure to UV light which enhances its antigenicity leading to more antibody formation and immune-mediated organ damage. Hence, people with LN are also advised sun protection in the form of sunscreens, wide-brimmed hats and full-sleeved shirts.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLAS) and lupus nephritis

APLAS is characterized by the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, recurrent thrombotic events and/or foetal loss. Patients with SLE have considerably higher thrombotic events than the general population. The major contributor for pro-thrombotic state in SLE is antiphospholipid antibodies; however, other traditional factors such as hyperlipidaemia, ageing, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, male sex, disease activity and drugs such as corticosteroids also add, initiate or propagate the pro-thrombotic state of SLE24. SLE is the most common cause of APLAS. The antiphospholipid syndrome nephropathy (APSN) is a classical feature of renal involvement with APLAS and it is characterized by microthrombi in acute phase followed by evidence of recanalization and fibrous intimal hyperplasia in chronic APSN. APSN can occur in patients with SLE with or without LN. The presence of aPL antibodies is associated with worse renal outcomes. Similarly, around 20-30 per cent of patients with SLE have histopathological lesions consistent with APSN. The biopsy diagnosis becomes necessary in such a scenario as treatment of APSN is anticoagulation whereas LN will require immunosuppression26.

Pregnancy in lupus nephritis

SLE most commonly affects women in their childbearing age. Pregnancy in lupus is associated with increased risk of preeclampsia, premature labour, thromboembolic events, infections, increased haematological and LN flare in mother and increased risk of intrauterine growth retardation, neonatal lupus and preterm birth87. The presence of Ro and La antibodies is associated with increased risk of congenital heart block (CHB) and requires frequent surveillance in pregnancy. The CHB usually develops during 18-24 wk of gestation87. According to EULAR/ERA-EDTA and KDIGO, pregnancy may be planned in stable patients with inactive lupus and UPCR <50 mg/mmol, for the preceding six-months, with GFR that should preferably be >50 ml/min. Drugs such as CYC, MMF, ACEI and ARB should not be used in pregnancy. Acceptable drugs during pregnancy are HCQ, low-dose prednisone, AZA and CNI. The treatment should not be reduced in preconception period and during pregnancy. The patient should be continuously followed up every four weeks in the first half of pregnancy and then every 1-2 wk during latter half of pregnancy. Acetylsalicylic acid should be considered to reduce the risk of preeclampsia. The use of HCQ has been found helpful in reducing various maternal and foetal complications in pregnant lupus patients2426.

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) in lupus nephritis

Progression of LN to ESRD is usually associated with remission of extrarenal features of SLE in most of the patients88. Approximately 10-30 per cent of the patients with LN reach ESRD over 15 years despite aggressive treatment8990. According to the recent US data, the overall rates of ESRD in LN have stopped increasing over the last decade91. According to EULAR/ERA-EDATA26, the outcome of patients with LN-associated ESRD on haemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis is comparable, though HD is associated with vascular thrombosis-related complications, especially with antiphospholipid antibodies and increased rate of infections in later modality. Renal transplant offers the best rehabilitation for most lupus patients with ESRD91. The allograft survival rates in lupus and non-lupus transplant recipients are similar. Transplantation should be performed once lupus is quiescent, for at least six (3-12) months. The results are better for living-donor92 though those with antiphospholipid antibodies have a higher graft failure risk. Post-renal transplant recurrence of LN is uncommon (2-11%) and usually does not compromise long-term graft outcome26909293.

Conclusion

With the current treatment, LN has evolved from incurable to a disease which can be controlled with trade-off between improved outcomes and therapy-related adverse events. Objective criteria for renal biopsy assessment and their utilization for the treatment have made therapy almost similar worldwide though lupus is known to behave differently across races and ethnicities. Low-dose iv CYC or MMF has been suggested as an induction agent for proliferative LN along with tapering course of steroids. However, high-dose iv CYC or MMF may be preferred in patients with crescentic LN associated with loss of GFR. Target dose of MMF of 2 g/day during induction and 1g/day during maintenance may be adequate for patients of the Indian subcontinent. AZA and MMF have performed almost equally as maintenance agent, both in safety and efficacy outcome parameters in various studies across the globe. AZA has been suggested as maintenance agent as it offers advantage of being cheap and is safe for use in pregnancy. Multitarget therapy can be an option in patients with resistant LN. Biologicals, especially RTX although still off the shelf as induction agent, can be used for resistant LN. Overall, treatment has to be individualized, multidisciplinary and holistic to prevent loss of organ function. Still, we need new, safe and specific drugs and uniform disease and outcome-related definitions so that knowledge across the world can be put to an optimal use.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Lupus nephritis. Classification, prognosis, immunopathogenesis, and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20:213-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: The Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2121-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 10-year follow-up data of the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial comparing low-dose and high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:61-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide with oral mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2016;89:235-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil or intravenous cyclophosphamide for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2219-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- [Google Scholar]

- Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics and the 1997 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus in a real-life scenario. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:437-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunoglobulin G subclass of human antinuclear antibodies. Clin Exp Immunol. 1970;6:145-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney-infiltrating CD4+ T-cell clones promote nephritis in lupus-prone mice. Kidney Int. 2012;82:969-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lupus nephritis: From pathogenesis to targets for biologic treatment. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;128:224-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetics and pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:329-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic factors predisposing to systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:164-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proliferative lesions and metalloproteinase activity in murine lupus nephritis mediated by type I interferons and macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3012-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review: Lupus nephritis: Pathologic features, epidemiology and a guide to therapeutic decisions. Lupus. 2010;19:557-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:241-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical-morphological features and outcomes of lupus podocytopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:585-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Glomerulonephritis. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Available from: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=38244

- American College of Rheumatology guidelines for screening, treatment, and management of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:797-808.

- [Google Scholar]

- Joint European League Against Rheumatism and European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of adult and paediatric lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1771-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of renal functional outcome in lupus nephritis: A single centre retrospective study. QJM. 2008;101:313-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Value of a complete or partial remission in severe lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:46-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapy of lupus nephritis. Controlled trial of prednisone and cytotoxic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:614-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controlled trial of pulse methylprednisolone versus two regimens of pulse cyclophosphamide in severe lupus nephritis. Lancet. 1992;340:741-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide, alone or in combination, in patients with lupus nephritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:549-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azathioprine/methylprednisolone versus cyclophosphamide in proliferative lupus nephritis. A randomized controlled trial. Kidney Int. 2006;70:732-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term efficacy of azathioprine treatment for proliferative lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:969-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment with cyclophosphamide delays the progression of chronic lesions more effectively than does treatment with azathioprine plus methylprednisolone in patients with proliferative lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:924-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial of azathioprine/methylprednisolone versus cyclophosphamide in patients with proliferative lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:966-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil therapy in lupus nephritis: Clinical observations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:833-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. Hong Kong-Guangzhou Nephrology Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1156-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aspreva Lupus Management Study Group. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1103-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tacrolimus for induction therapy of diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis: An open-labeled pilot study. Kidney Int. 2005;68:813-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized, controlled trial of prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine in lupus membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:901-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nat Med. 2008;14:931-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Success using tacrolimus in patients with proliferative and membranous lupus nephritis and refractory proteinuria. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72(9 Suppl 4):18-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tacrolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil for induction therapy of lupus nephritis: A randomised controlled trial and long-term follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:30-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of class V+IV lupus nephritis with multitarget therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2001-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multitarget therapy for induction treatment of lupus nephritis: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:18-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term tacrolimus-based immunosuppressive treatment for young patients with lupus nephritis: A prospective study in daily clinical practice. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;121:c165-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term data on tacrolimus treatment in lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:2232-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sequential therapies for proliferative lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:971-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil for long-term immunosuppression in lupus nephritis: Results from the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2083-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1886-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine in the maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis. Ren Fail. 2008;30:865-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis: A meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2013;18:104-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis with mycophenolate or azathioprine: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53:834-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-/off-label use of biologic therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. BMC Med. 2014;12:30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of rituximab in moderately-to-severely active systemic lupus erythematosus: The randomized, double-blind, phase II/III systemic lupus erythematosus evaluation of rituximab trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:222-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- B-cell depletion in SLE: Clinical and trial experience with rituximab and ocrelizumab and implications for study design. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(Suppl 1):S2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of epratuzumab in patients with moderate/severe active systemic lupus erythematosus: Results from EMBLEM, a phase IIb, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:183-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: Results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atacicept in combination with MMF and corticosteroids in lupus nephritis: Results of a prematurely terminated trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of rituximab in patients with active proliferative lupus nephritis: The Lupus Nephritis Assessment with Rituximab study. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1215-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beyond the LUNAR trial. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory lupus nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:106-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of belimumab treatment on renal outcomes: Results from the phase 3 belimumab clinical trials in patients with SLE. Lupus. 2013;22:63-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mizoribine: A new approach in the treatment of renal disease. Clin Dev Immunol 2009 2009:681482.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination therapy with steroids and mizoribine in juvenile SLE: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:877-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction treatment of proliferative lupus nephritis with leflunomide combined with prednisone: A prospective multi-centre observational study. Lupus. 2008;17:638-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of leflunomide in the treatment of lupus nephritis refractory or intolerant to traditional immunosuppressive therapy: An open label trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:417-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is activated in murine lupus nephritis and downregulated by rapamycin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:498-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- A controlled trial of plasmapheresis therapy in severe lupus nephritis. The Lupus Nephritis Collaborative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1373-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic plasma exchange in paediatric SLE: A case series from India. Lupus. 2015;24:889-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment of lupus nephritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;29:321-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intravenous immunoglobulin compared with cyclophosphamide for proliferative lupus nephritis. Lancet. 1999;354:569-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure after intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:347-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Previous antimalarial therapy in patients diagnosed with lupus nephritis: Influence on outcomes and survival. Lupus. 2008;17:281-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of hydroxychloroquine on renal damage in patients with lupus nephritis: LXV, data from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:830-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin inhibition or blockade for the treatment of patients with quiescent lupus nephritis and persistent proteinuria. Lupus. 2005;14:947-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antiproteinuric effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and an angiotensin II receptor blocker in patients with lupus nephritis. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:892-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- LUMINA (LIX): A multiethnic US cohort. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors delay the occurrence of renal involvement and are associated with a decreased risk of disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus – results from LUMINA (LIX): A multiethnic US cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1093-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mixed bone marrow or mixed stem cell transplantation for prevention or treatment of lupus-like diseases in mice. Exp Nephrol. 2002;10:408-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesenchymal stem cells are a rescue approach for recovery of deteriorating kidney function. Nephrology (Carlton). 2012;17:650-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cell-based cell therapy for glomerulonephritis. Biomed Res Int 2014 2014:124730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lupus nephritis: Treatment of resistant disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:154-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discontinuation of immunosuppression in proliferative lupus nephritis: Is it possible? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1465-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Managing lupus patients during pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:435-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-stage renal disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;21:2-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- End-stage renal disease in lupus: Disease activity, dialysis, and the outcome of transplantation. Lupus. 1998;7:654-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of lupus nephritis associated with end-stage renal disease. G Ital Nefrol. 2008;25(Suppl 44):S68-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESRD from lupus nephritis in the United States, 1995-2010. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:251-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of renal transplantation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1997;27:17-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors and impact of recurrent lupus nephritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus undergoing renal transplantation: Data from a single US institution. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2757-66.

- [Google Scholar]