Translate this page into:

Choosing the right model for STEMI care in India – Focus should remain on providing timely fibrinolytic therapy, for now

*For correspondence: karthik2010@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the treatment of choice for the management of acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), when it can be provided within 120 min of diagnosis1-3. The timely provision of primary PCI presents major logistical challenges. In countries like the United States, which has a large number of cardiac catheterization facilities, many patients with STEMI do not present to PCI-capable hospitals4. These patients are then transferred for primary PCI, but only about a fifth of them achieve the recommended transfer-in door-to-balloon time of ≤90 min5. Consequently, based on the evidence from recent randomized trials, guidelines recommend fibrinolytic therapy followed by elective PCI between 2 and 24 h (a pharmaco-invasive strategy), for patients who are unlikely to receive timely primary PCI2,3.

In India, there are far fewer PCI-capable hospitals providing round-the-clock primary PCI facilities than in most developed countries, and the vast majority of patients with STEMI present to non-PCI-capable hospitals. As a result, only about 5-10 per cent of patients with STEMI, who are eligible for reperfusion, undergo primary PCI6. Even in the States with well-developed healthcare infrastructure, the proportion of patients undergoing primary PCI is less than 15 per cent6,7. It would therefore appear that a pharmaco-invasive strategy is ideally suited for a country like India. Some investigators have recently created hub-and-spoke networks to facilitate transfer of patients to PCI-capable hospitals with a view to improving the rates of primary and pharmaco-invasive PCI in the State of Tamil Nadu. Based on the limited observational data obtained from this experience8, there is a movement to scale up this model nationally.

We believe that such a model will be costly to implement and is unlikely to yield the expected benefits to patients who suffer a STEMI in this country. Here, we draw on the pathobiology of acute coronary occlusion and on the available data on Indian patients presenting with STEMI, to demonstrate why a focus on improving primary and pharmaco-invasive PCI may be misguided.

Myocardium dies rapidly after coronary occlusion

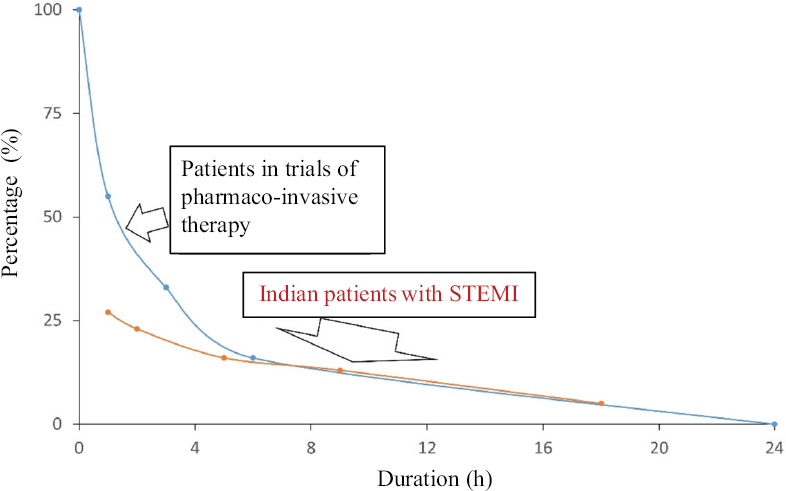

Both experimental and clinical data suggest that the amount of salvageable, reversibly injured myocardium reduces exponentially following coronary occlusion. In anaesthetized dogs, nearly 40 per cent of myocardium became nonviable 40 min after occlusion, rapidly progressing to 57 per cent at three hours and 71 per cent at six hours9. This rapid loss of viability is also mirrored by a rapid fall in the relative benefits of fibrinolytic therapy with time to treatment10. In meta-analyses of the fibrinolytic therapy trials, the proportional mortality reduction with fibrinolysis was 26 per cent in patients treated within three hours, falling to 18 per cent for those treated between four and six hours, and just 14 per cent between seven and 12 h11. This is depicted in the Figure. The curves suggest that for reperfusion therapy to be effective, it has to be provided within 3-6 h (corresponding to the steep portion of the curve). Treatment beyond six hours (in the flat portion of the curve) yields far less benefit.

- Relationship between time from coronary occlusion and experimental and clinical measures of myocardial salvage. Figure depicts remaining salvageable myocardium (blue dots) with time following experimental coronary occlusion9 and relative mortality reduction with fibrinolytic therapy (red dots) in relation to time from symptom onset10,11. Figure recreated from published data9-11. STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

Indian patients with STEMI present late

In India, the time from symptom onset to presentation to a treating hospital is the main component of pre-hospital delay among patients with STEMI. Typically, patients present beyond 5-6 h after symptom onset and as late as 10-13 h (Table I)7,12-16. In a large registry from the State of Kerala, over 40 per cent of patients presented beyond six hours after symptom onset6. This may be due to several factors, including a failure to recognize the seriousness of symptoms, non-availability of ambulance services and onward referral without treatment at the point of first medical contact (FMC)7. Delays may also be due to the difficult terrain making transport times long. For example, the median time from symptom onset to presentation was 13 h in the Himachal Pradesh ACS Registry14. Therefore, on average, Indian patients with STEMI present in the flat portion of the myocardial salvage curve (Figure), where the effect of even the most efficient reperfusion modalities may be minimal. Further, between 35 and 65 per cent of patients present beyond 12 h and do not receive any reperfusion therapy. Consequently, the largest benefits are likely to accrue from policies and interventions which aim to reduce this pre-hospital delay.

| Study, year, n (number of STEMI patients) | Time from symptom onset to FMC (min) | Time from symptom onset to fibrinolysis (min) | Proportion of patients not receiving any reperfusion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CREATE registry7, 2008, n=12,405 | 300 | 350 | 31 |

| HP ACS registry14, 2016, n=2641 | 780 | NR | 64.4 |

| Iqbal and Barkataki13, 2016, n=510 | 600 | 630 | 59.2 |

| ACS QUIK12, 2018, n=13,689 | 240 | 305 | 28 |

| YOUTH registry16, 2019, n=787 | 340 | NR | 42 |

| Sharma et al15, 2021, n=1203 | 600 | NR | 48 |

STEMI, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; FMC, first medical contact; NR, not reported

Pharmaco-invasive therapy is useful only in patients who present early

The primary mechanism of benefit of elective angioplasty performed within 24 h after fibrinolysis is likely through the prevention of re-occlusion that occurs in about 10 per cent of patients after fibrinolytic therapy17. For example, in the Trial of Routine Angioplasty and Stenting after Fibrinolysis to Enhance Reperfusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction, the difference in the composite primary outcome was driven by the reduction in recurrent ischaemia or infarction in the patients who underwent elective angioplasty after fibrinolysis18. Parenthetically, for prevention of re-occlusion of the infarct-related artery to make a difference, sufficient myocardium must be salvaged by the preceding fibrinolytic therapy. A review of the trials of pharmaco-invasive therapy suggests that the time from symptom onset to presentation is typically less than two hours, with fibrinolysis being provided shortly thereafter (Table II)18-24. Therefore, the evidence for the benefit of pharmaco-invasive therapy comes exclusively from patients who present in the steep portion of the myocardial salvage curve (Figure). There is currently no evidence to indicate that patients who present beyond 2-3 h after symptom onset, particularly those who present in the flat portion of the myocardial salvage curve, will benefit from a pharmaco-invasive approach.

| Study, year, n | Time from symptom onset to FMC (min) | Time from symptom onset to fibrinolysis (min), in the pharmaco-invasive arm |

|---|---|---|

| SIAM-III19, 2003, n=163 | NR | 216 |

| GRACIA-120, 2004, n=499 | NR | 187 |

| CAPITAL-AMI21, 2005, n=170 | 68 | 120 |

| WEST22, 2006, n=304 | 76 | 130 |

| CARESS-in-AMI23, 2008, n=598 | 120 | 165 |

| TRANSFER-AMI18, 2009, n=1059 | 86 | 113 |

| NORDISTEMI24, 2010, n=266 | 67 | 117 |

NR, not reported; FMC, first medical contact

Towards evidence-based programmes and policy

Treatment of STEMI presents a good example of a situation where evidence generated elsewhere cannot be extrapolated indiscriminately to the Indian context. There is a need to generate high-quality evidence locally to inform policy. Observational data have well-known limitations and must not be the sole basis for designing new programmes, particularly when, as in this case, major increases in healthcare spending are involved. The transfer of all patients to PCI-capable hospitals involves provisioning for new transport and catheterization laboratory infrastructure and workforce. Secondly, programme objectives should be chosen based on local needs and the best available evidence. Given that most patients across the country present late after symptom onset, and that a substantial number of them do not receive any fibrinolytic therapy, it is obvious that the most appropriate point of focus of any STEMI treatment programme should be on these two metrics. There is overwhelming evidence to suggest that this would yield the greatest improvement in patients’ outcome11. Having multiple additional objectives can have the unanticipated consequence of undermining the primary focus. For example, in the Tamil Nadu STEMI model (which was aimed at facilitating transport for primary PCI or pharmaco-invasive PCI), the proportion of patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy actually reduced (from 67 to 50%) after implementation of the programme, without increasing the overall rate of reperfusion8. These patients were presumably transferred for primary PCI, but it is unclear from the published data if this was performed in a timely manner. This may be a reflection of the ‘reperfusion paradox’ that has been observed in the context of choosing between primary PCI and fibrinolysis4. Armstrong and Boden4 noted that in a futile attempt to offer timely primary PCI, the opportunity for timely fibrinolysis was being foregone.

Finally, India is a large country with major differences in healthcare infrastructure between the States (and even districts). Therefore, a one-size-fits-all model of STEMI care for the country would be misguided and wasteful. Based on the available evidence, we suggest that any model of STEMI care in India should have the principal objectives of improving the rates of fibrinolysis, and reducing the time from symptom onset to FMC, and treatment. These can be achieved by ensuring the performance of ECGs at the point of FMC, enable their prompt interpretation (by on-site or off-site personnel) and prompt initiation of bolus fibrinolytic therapy. This approach has resulted in a near doubling of the proportion of patients who received fibrinolytic therapy in the ICMR STEMI-ACT Programme in Shimla (36.7 to 60.2% one year after implementation; unpublished data from annual report submitted to the ICMR). Programmes can be selectively upgraded (at the district or State levels) to include transfer of patients for elective PCI after fibrinolysis, once timely fibrinolysis is routinely provided (time from symptom onset to treatment between 2 and 4 h). However, if investigators believe that a pharmaco-invasive strategy may be appropriate even at longer times to fibrinolysis, they should produce strong evidence in the form of pragmatic randomized trials. Such an approach offers the best way forward for improving STEMI care in India.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction:A quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation:The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for coronary artery revascularization:A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e21-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reperfusion paradox in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:389-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatments, trends, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:254-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentation, management, and outcomes of 25 748 acute coronary syndrome admissions in Kerala, India:Results from the Kerala ACS Registry. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:121-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in India (CREATE):A prospective analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2008;371:1435-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- A system of care for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in India:The Tamil Nadu-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction program. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:498-505.

- [Google Scholar]

- The wavefront phenomenon of ischemic cell death. 1. Myocardial infarct size vs. duration of coronary occlusion in dogs. Circulation. 1977;56:786-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction:Reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet. 1996;348:771-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of a quality improvement intervention on clinical outcomes in patients in India with acute myocardial infarction:The ACS QUIK Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319:567-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of acute coronary syndrome in North Eastern India –A study from a major center. Indian Heart J. 2016;68:128-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological profile, management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome:Single centre experience from a tertiary care hospital in North India. Indian Heart J. 2021;73:174-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The young myocardial infarction study of the western Indians:YOUTH Registry. Glob Heart. 2019;14:27-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reocclusion:The flip side of coronary thrombolysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:766-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2705-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial effects of immediate stenting after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:634-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Routine invasive strategy within 24 hours of thrombolysis versus ischaemia-guided conservative approach for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (GRACIA-1):A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1045-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined angioplasty and pharmacological intervention versus thrombolysis alone in acute myocardial infarction (CAPITAL AMI study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:417-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs. primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1530-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the combined abciximab reteplase stent study in acute myocardial infarction (CARESS-in-AMI):An open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008;371:559-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of immediate angioplasty versus ischemia-guided management after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction in areas with very long transfer distances results of the NORDISTEMI (NORwegian study on DIstrict treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:102-10.

- [Google Scholar]