Translate this page into:

Challenges faced by frontline health managers during the implementation of COVID-19 related policies in India: A qualitative analysis

For correspondence: Dr Anusha Rashmi, Department of Community Medicine, K.S. Hegde Medical Academy, Deralakatte, Mangalore 575 018, Karnataka, India e-mail: anurash7@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the strengths and weaknesses of the healthcare systems across the world. Many directives, guidelines and policies for pandemic control were laid down centrally for its implementation; however, its translation at the periphery needs to be analyzed for future planning and implementation of public health activities. Hence, the objectives of this study were to identify the challenges faced by frontline health managers in selected States in India during the pandemic with regard to implementation of the COVID-19-related policies at the district level and also to assess the challenges faced by the them in adapting the centrally laid down COVID-19 guidelines as per the local needs of the district.

Methods:

A qualitative study using the grounded theory approach was conducted among frontline district-level managers from eight different States belonging to the north, south, east and west zones of India. The districts across the country were selected based on their vulnerability index, and in-depth interviews were conducted among the frontline managers to assess the challenges faced by them in carrying out COVID-19 related activities. Recorded data were transcribed verbatim, manually coded and thematically analyzed.

Results:

Challenges faced in implementing quarantine rules were numerous, and it was also compounded by stigma attached with the disease. The need for adapting the guidelines as per local considerations, inclusion of components of financial management at local level, management of tribal and vulnerable populations and migrants in COVID context were strongly suggested. The need to increase human resource in general and specifically data managers and operators was quoted as definite requirement.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The COVID-19 guidelines provided by the Centre were found to be useful at district levels. However, there was a need to make some operational and administrative modifications in order to implement these guidelines locally and to ensure their acceptability.

Keywords

Challenges

COVID-19

district level

multicentric

policy implementation

qualitative analysis

quarantine

The disease COVID-19, first reported from Wuhan, China, rapidly gained foothold on various parts of the globe resulting in a novel pandemic1. India reported its first case on January 30, 20202. It came up as a classic example of the need for collaboration and knowledge sharing not only between the various sectors within a country but also different countries across the world. When working conditions, technology and knowledge are constantly changing, the top-down approach may be adopted to have uniformity in implementing action plans.

As a country with its diversity in culture, traditions and beliefs, India took time to assimilate various deviations from the norm that COVID-19 demanded. Amid the rising number of cases of new COVID-19 cases, India, as a nation, was experiencing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic from the very start3,4. A drastic increase in cases put the nation in a difficult situation5-9. The course of the COVID-19 pandemic elucidated the vital role played by data in guiding effective decisions to save communities and economies worldwide. With no prior knowledge of the virus, the course of the disease, and its spread, data were the one reliable source used by countries to guide the decision-making process and verify the plan of action before it is committed10. While the management of COVID-19 patients was one side of the issue; on the other hand, administrative and managerial roadblocks were prominent. The health system itself was facing a never-before situation during the current pandemic. Although the implementation of lockdowns to prevent transmission all over the country was timely, despite all efforts, the health system faced challenges in terms of workforce, health facilities, economy, etc. Inadequate knowledge, spread of erroneous information and lack of awareness caused confusions and panic. The national advisories and guidelines rolled out from government agencies from time to time were helpful in managing situations to a great extent. However, at the same time, frontline managers faced varied challenges as they were the core team members responsible for prevention and control of COVID-19 in their respective jurisdictions. In this context, the present study was conducted with a broad objective of understanding the challenges faced by frontline health managers at the district level during the pandemic with regard to implementation of the COVID-19-related policies in India. Assessing the barriers faced by the frontline managers in adapting the centrally laid down COVID-19 guidelines as per the local needs of the district was another objective.

Material & Methods

After obtaining Institutional Ethical Committee clearance and the required permissions from the State and district authorities, a qualitative study using the grounded theory approach was conducted from August to December 2019 among frontline district-level health managers. Using multistage sampling, two States were selected from each of the north, south, east and west zones. The States that were selected purposively were Delhi and Rajasthan from north, Tripura and Odisha from east, Maharashtra and Gujarat from west and Kerala and Karnataka representing the south. The districts within these states were selected based on their vulnerability index11. In order to get a holistic representation, three districts each were selected from the very high/high, medium and low/very low vulnerability categories. From each of these three districts, four to five frontline managers were selected purposively based on their role in the COVID-19 pandemic control activities. This included District Health Officer (CMHO; Chief Medical & Health Officer), District Surgeon and a member from district administration who was part of COVID-19 district task force. One person from administration, who was not related to the health system, was also included. Apart from the district-level managers, one block-level manager was included to identify the ground-level challenges. Considering 5-6 managers in all three districts of each state and thus from all eight states, a total of 120 frontline managers were selected for in-depth interviews (IDIs).

Informed consent (written for in-person interviews and oral for online interviews) was obtained from the respondents. Due to the prevailing COVID-19 restrictions, the IDIs were conducted either through Zoom or in-person or by telephone as feasible. The interviews were conducted by faculty members from medical colleges who were trained and had experience in conducting qualitative studies. The interview guides were prepared by the core team of investigators after extensive formative research which included literature reviews, expert opinions and piloting of the IDI guide. The site investigators were trained through online sessions on how to conduct the interviews in order to fulfil the objectives of the study. To ensure data quality, the lead investigator or lead co-investigator was present virtually during initial interviews to observe and to guide, following which independent interviews were carried out by the site investigators. In addition, with the aid of questionnaires and vignettes, participants were requested to share their experiences either as stories or as case studies. Each of the interviews lasted for about 30-45 min. At each district, the interviews were conducted till data saturation was obtained and no new themes arose. Out of the total 120 interviews conducted, 20 were conducted via telephone, while 50 each were conducted through Zoom meetings and in-person interviews. All interviews were either audio or Zoom recoded after obtaining permissions in addition to maintaining investigators’ diaries. They were then transcribed verbatim, manually coded and thematically analyzed, which were then verified independently by two investigators to increase the validity of the findings. The discrepancies that evolved were resolved through discussion till consensus was reached between the investigators; inferences were made using investigator triangulation.

Results

The results have been tabulated as general challenges (Table I), specific challenges (Table II) and local cope-up mechanisms (Table III).

| Theme | Subthemes | Related verbatims |

|---|---|---|

| Problems due to geographical location | Inadequate for local needs | ‘When a disease with no experience comes, State and Centre Health Authorities should send people to just be with the district, get experience and give feedback so that better guidelines for the area can be framed’ KP2 ‘Containment zone went into the sea too due to distance and it was such a such a waste of resources’ MH2 |

| Issues with isolation | ‘Home isolation in slums was impossible as the house with 10×10 space where ˂12 people have to live. Earlier at least some residents of the house, used to work in the day and some in the night shift. Lockdown had created everyone to sit at home and so overcrowding and where could we home isolate’ MH4 | |

| Conflicts with regard to authority issuing guidelines | ‘One query is why guidelines are issued by ICMR and not by MoHFW’ GJ1 | |

| Problems due to absence of specific guidelines | Absence of guidelines for tribal areas | ‘SOPs are required in tribal areas. There we must get separate SOPs. Organizing camps there and time schedule is also different in the tribal area’ TR3 |

| Issues with micro-management | ‘No guidelines for micro-containment were available from the Centre or the State’ MH4 ‘International travel should be stopped with immediate effect in case of any such pandemics in the future’ DH2 | |

| Issues in keeping up with guidelines | Frequent change of guidelines | ‘Here, the rules are in paper only, and there is a need for mock drill’ GJ3 ‘Reaching of the guidelines was not an issue; it reached on time and was disseminated. Understanding of the guidelines and acting could be a problem as the guidelines changed frequently’ MH2 |

MoHFW, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; SOP, standard operating procedures; ICMR, Indian Council of Medical Research

| Themes | Subthemes | Related verbatims |

|---|---|---|

| Issues related to migrants | Management of migrants | ‘Unlocked migrants started walking on the road, many from Mumbai and Bihar’ MH3 ‘There was an exhaustive list of travellers, not even filtered’ and it took time to screen all of them. They recounted, saying ‘we started a new initiative of reverse quarantine; guidelines for these came later on’ DH3 |

| Issues related to doctors | Prophylaxis-related issues | ‘Most of us took HCQ till recently and drug was prescribed for more than a month and then came a approach of no usage of HCQ. So, neither we did right decision at the right time, nor we stayed neutral. We went aggressively wrong. Evidence published for treatment which was ordered earlier came to us quite late and we had to follow non-evidence based orders as per central say’ |

| Quarantine for doctors | ‘Our 80 per cent doctors were already working in many places-quarantine center’s, dispensaries and other activities with 20 per cent of doctor’s quarantine of doctors was not possible’ RJ3 ‘Our doctors were very co-operative during this phase’ KP5 ‘For the staff, we could not give seven days’ quarantine-however they were given only four days’ OP4 | |

| Trouble with VIP patients | Too much of political and bureaucratic involvement made coordination difficult MH4 | |

| Issues in the community | Spread of false news | ‘A lecturer had shared false news on Facebook and we had arrested him and sent him to jail. Further, 50 to 60 people in our district violated the rules for the containment zone. We registered a case against them under the national disaster act due to which people became careful’ TR7 ‘They think doctors get paid for every positive patient’ KA6 ‘People were apprehensive of getting admitted to CCC’, If you go the hospital, you will test positive’ OP4 |

| Problems due to changing rules | ‘People were with government, but the government needs to understand that proper growth and change to sink in people takes time’ DH2 | |

| Apprehensions | ‘Fishermen community, they are resistant to testing as they are otherwise healthy and because of a positive result on testing they have to lose out on 10 days job’ KP11 ‘After we declared one area as containment zone, the people of other areas became apprehensive and they themselves treated their living area as containment zone and did not allow others in and created havoc in the system’ OP2 |

HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; VIP, very important person; CCC, COVID care center

| Themes | Subthemes | Related verbatims |

|---|---|---|

| Work management | Delegation of work | ‘We have a district data manager. And we have five urban data managers working under him who helped us manage the data and the databases’ KP3 ‘We used to talk to all level people and we had village level committee for COVID, which was made. We delegated a lot of decision making to field officers during the lockdown, which allowed grass-root level workers to tailor the standards as per local and social needs of the public in their respective areas’ KP 6 |

| Utilizing technology | ‘Monitoring is done through the health survey app. In rural areas, monitoring is from PHCs. Through GPRS tracking, we get information about breach of quarantine. Mobile testing labs have been established. Incentive-based recruitment of workforce is done, and App-based monitoring of quarantine is done’ MH7 | |

| Conducting training | ‘We did strong IEC in panchayats and did activities like MASK day, and it is still going on’ DH8 ‘Even before starting every single CCC, we have had a detailed training module for all our sanitary workers also by our WHO consultant’ KA2 | |

| Allaying public fear | Utilizing media for dissemination of information | ‘We used multiple ways to talk to the general public including the social media and websites to educate people and later they started understanding the procedure’ OP4 |

| Involving religious leaders | ‘We had to take the confidence of religious leaders as mind set and behaviour pattern are led by communal leaders’ KP11 | |

| Utilizing routine care facility for COVID check-up | ‘During the antenatal check-up, we did swab test of all pregnant mothers. Furthermore, after that, we provide them MAMTA card’ KP11 |

PHC, primary health centre; GPRS, general packet radio service; WHO, World Health Organization; MAMTA, mother and child tracking system; IEC, information, education and communication

Frontline health managers appreciated that the guidelines developed by the Central Government Departments and Agencies, were disseminated adequately, were comprehensive and drafted in detail. However, initially there were no guidelines for dead body disposal, managing the tribal population, etc.

The frequent changes in the criteria of containment zone and home isolation resulted in confusion. For example, in Mumbai, it was challenging to manage the containment and home isolation practices. There was a felt need for guidelines on areas like the financial management of various activities. There were guidelines to conduct Information, Education and Communication (IEC) through audio-visual aids with no mention of funding for the same (to buy projector or TV), and reimbursements were declined, quoting that guidelines did not support the same. With no specific guidelines on managing migrants, the frontline managers struggled to keep up with the large population coming in from other States. Local adaptations of these guidelines such as distancing at market areas, management at borders and communication to the public had not been disseminated. There was a lot of stigma associated with quarantine and containment zones. At a few sites, translation of guidelines which were essential for training personnel, into the local language posed difficulty, and this was time-consuming.

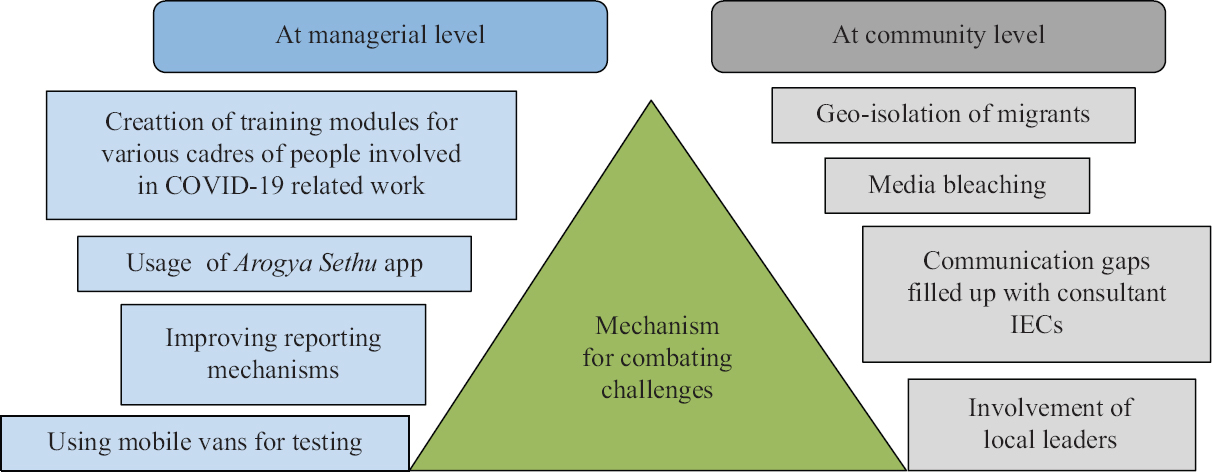

A few frontline managers felt that the COVID-19 management guidelines were different from available evidence in scientific literature and many doctors could not be convinced about the guidelines. Healthcare managers felt that the treatment protocol was drafted without discussion with treating physicians. At some sites, the managers felt that although there was a frequent change in guidelines, it was professionally managed. Many districts came up with mechanisms to overcome the barriers they were facing (Figure). States with data managers worked better. The States analyzed local data to develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) and guidelines as per local needs and acceptability. Many believed in the delegation of decision.

- Various mechanisms of combatting challenges adopted at district levels. IEC, information, education and communication

In some places, people themselves declared a containment zone and avoided people in such zones. Some had initiated the reverse quarantine guidelines prioritizing the elderly and those with comorbidities.

However, home quarantine implementation came as a boon later to sort out most of the issues. In order to manage COVID-19 related issues effectively and to provide better services, health authorities identified a few hospitals as COVID-19 hospital and others as non-COVID-19 hospitals. But later, the non-COVID hospitals showed resistance in taking up COVID-19 related work.

Discussion

The COVID-19 related guidelines were drafted with the broader goal of managing prevention and care issues. This study identified variations in adoption of guidelines across different States within India. Some States put forth several technical committees for the adaptation of guidelines as per their local needs. States that could not do modifications faced a few difficulties. The finding of this study is in line with a study conducted to identify barriers using the decision making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) model, which identified lack of administrative commitment, and support at community level as two among many other factors that challenged the implementation of public health measures2. District administrators in our study felt that during the later stage of the pandemic, non-co-operation from non-COVID-19 hospitals added to the existing challenges. The same study also identified that the major challenges were lack of resources and timely communication to public12. It further quoted lack of appropriate government policies as another reason for failure of adopting suggested public health measures2. Our study also revealed the concerns raised by the participants about how issues related to budget, public fear and resistance along with frequent change in guidelines posed difficulties. However, these were overcome by continuous dialogues, maximum use of media to disseminate required information and thus acquiring community trust. The migrant population forms the highly vulnerable sector in any country. The findings in our study regarding migrants were echoed in other investigations with regard to difficulties in managing the migrant population as they formed a huge sector for whom officials faced challenges, especially while providing quarantine facilities. The travel restrictions also affected this sector of population heavily13,14.

The influence of local religious leaders and political parties played a significant role in accepting or denying policies at the local level. A study done by Dutta and Fischer15 showed how important local governance had been for carrying out response to COVID-19. While administrative authorities rely heavily on local level institutions for many different aspects of response. There were many actions that only local institutions coordinating capacity could do15. There were false news of doctors getting paid heavily for every COVID-19-positive patient and that they were randomly making their tests positive. Health system streghthening and its relevance was a major concern in COVID-1916.

To conclude, it was observed that the COVID-19 guidelines provided by the Centre were found to be useful at the district level. However, there was a need to make some operational and administrative modifications to implement these guidelines locally and to ensure its acceptability. Findings of this study highlighted that the central directives and policies would have done better by providing space for flexibility for their implementation at the district levels to address the managerial issues vis a vis the local needs. The need for pooling of resources at the district level along with community participation for effective implementation of public health activities was also highlighted. Even though COVID-19 management at the district level was found to be challenging due to the limited resources, most of the frontline managers agreed that it was an important learning experience. They even developed innovative methods for implementing the directives and policies put forward by the central health authorities. However, all frontline managers unanimously emphasized the importance of the role played by media and community participation for successful implementation of the COVID-19 policies and guidelines.

This study had a few limitations in terms of being conducted as a rapid appraisal across the country. Due to the feasibility issues, the study had to remain restricted regarding representation of the frontline managers at the district level.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi (HIV/COVID 19/13/5/2020/ECD-II).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the entire COVID-19 Trailblazer Probe Team for their support in data collection from across various sites in the country.

References

- Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care. 2020;34:655-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- First confirmed case of COVID-19 infection in India: A case report. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:490.

- [Google Scholar]

- The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:717-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: Lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:3113-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Novel coronavirus. Available from: https://main.mohfw.gov.in/diseasealerts/novel-corona-virus

- Government of India. COVID-19 update: COVID-19 India. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/

- PM Modi calls for ‘Janata Curfew’ on March 22 from 7 AM-9 PM; 2020. Available from: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/pm-modi-calls-for-janta-curfew-on-march-22-from-7-am-9-pm/article31110155.ece

- Healthcare delivery in India amid the Covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Indian J Med Ethics 2020 Doi: 10.20529/IJME.2020.064

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of COVID-19 pandemic data in India: Challenges faced and lessons learnt. Front Big Data. 2021;4:790158.

- [Google Scholar]

- A vulnerability index for the management of and response to the COVID-19 epidemic in India: An ecological study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1142-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analyzing barriers for implementation of public health and social measures to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 disease using DEMATEL method. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:887-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges to the implementation and adoption of physical distancing measures against COVID-19 by internally displaced people in Mali: A qualitative study. Confl Health. 2021;15:88.

- [Google Scholar]

- The local governance of COVID-19: Disease prevention and social security in rural India. World Dev. 2021;138:105234.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strengthening health systems by health sector reforms. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:23568.

- [Google Scholar]