Translate this page into:

Causes of late-presenting developmental dislocation of the hip beyond 12 months of age: A pilot study

For correspondence: Dr Ritesh Arvind Pandey, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna 801 507, Bihar, India e-mail: riteshpandey8262@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), when detected early, can usually be managed effectively by simple methods. A delayed diagnosis often makes it a complex condition to treat. Late presentation of DDH is fairly common in developing countries, and there is scarcity of literature regarding the epidemiology and reason for late presentation. Through this study, we attempted to identify the reasons for late presentation of DDH in children more than 12 months of age.

Methods:

Fifty four children with typical DDH and frank dislocation of hip in whom treatment was delayed for 12 months or more were included. Parents were interviewed with a pre-structured questionnaire and data were collected for analysis with Microsoft Excel 2016 and SPSS version 26.

Results:

Diagnostic delay was the most common reason for late presentation and was observed in 52 children (96.2%). The mean age at diagnosis was 24.7 months. The mean age at treatment was 37.3 months with a mean delay of 12.5 months from diagnosis and 22.1 months from initial suspicion. Physician-related factors contributed 55.3 per cent, while family and social issues accounted for 44.7 per cent of overall reasons for diagnostic and treatment delays.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Late presentation of DDH in walking age is common. Physician- and family-related factors accounted for most of these cases. Failure or inadequate hip screening at birth by the attending physician is a common reason for late diagnosis. The family members were unaware about the disorder and developed suspicion once child started walking with an abnormal gait.

Keywords

Children

delayed diagnosis

delayed treatment

developmental dysplasia of the hip

hip dislocation

late presentation

screening

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is one of the major hip disorders of childhood1. It is one of the most common congenital musculoskeletal disorders to present to a paediatrician. When left untreated, it results in a complex condition which is often difficult to treat. A painless limp or lurch is the most common presentation at walking age. Later, this can be associated with fatigue, pain, eventually leading to degeneration of the hip and spine2. When detected early, it can usually be managed effectively by simple non-operative methods3. Considering the fact that 95-98 per cent of DDHs are non-teratogenic with good prognosis, an early detection can potentially achieve a normal hip in these children. Therefore, neonatal screening programmes have been suggested and adopted in many jurisdictions4-6.

Late presentation of DDH is common in developing countries. A delayed diagnosis increases the need for surgery, thereby increasing cost of treatment and overall burden on healthcare facilities and families7. The result of delayed treatment is often less satisfactory than the outcome of early treatment. In the present era of consumer consciousness, this can lead to substantial malpractice claims3.

In a developing country like India, childbirth at home is still prevalent due to socioeconomic constraints of family and lack of healthcare facilities in some regions. The hip instability in these children may not be picked up early and hence left untreated4. However, it is common to miss this entity even in hospital deliveries questioning the competency and the effectiveness of screening methodology8. There is scarcity of literature regarding the epidemiology and causes of these late-presenting children in India. Through this study, an attempt was made to evaluate the reasons for late presentation of DDH into walking age.

Material & Methods

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted at Children’s Orthopaedic Centre, Mumbai, from 2013 to 2015, and at Christian Medical College (CMC), Ludhiana, from 2018 to 2020. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review/Ethics Committee of the respective institutes. Procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards laid down by the Indian Council of Medical Research ethical guidelines (2017)9 for biomedical and health research on human participants. All children of walking age, presenting to our outpatient department with developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH), were evaluated clinically and with radiograph of pelvis of both hips. Parents were interviewed by one of the authors with a pre-structured questionnaire after taking informed consent from them. An immediate caregiver (father/mother) was the informant for all the cases. Teratogenic and neurogenic subtypes were identified and excluded. Only typical DDH with frank dislocation of hip in whom treatment was delayed for 12 months or more was included in the study.

The questionnaire aimed to gather both demographic information and information with respect to known risk factors for DDH. It included both closed and open ended questions and aimed to collect quantitative as well as qualitative data on age, gender, residence (rural/urban), socioeconomic status of family (low, middle and high) and side of the extremity involved. Socioeconomic status was assessed by the modified Kuppuswamy scale, which included the education, occupation and monthly income of parents. Birth history was taken to document place of birth (home/hospital), type of birth [vaginal/lower segment caesarean section (LSCS)], gestational age (term/preterm) and type of presentation (cephalic/breech). Further detail about the type of hospital was inquired in case of hospital delivery (primary health centre, community health centre, district or government hospital, tertiary health centre, private nursing home and corporate hospital). History of any other associated congenital anomaly and history of any perinatal complications indicating a risk factor for DDH were also obtained. An attempt was made to know whether hip was screened at birth by asking if newborn was attended for this by any doctor. Furthermore, the speciality of the attending physician was asked and noted.

Detailed clinical and treatment history was taken till participation in the present study to understand the cause for delay. Information was gathered from previous medical record whenever available. The parents were asked for the age of child at which hip abnormality was suspected and who made initial suspicion (parents, physicians and neighbours). Initial symptoms that raised suspicion about possible hip abnormality were also inquired upon. The age at first consultation with a healthcare professional for hip abnormality was recorded. Time interval between suspicion and first consultation was calculated to reflect on parent’s attitude and awareness level towards DDH. Any reason for delay in consultation was sought. Age at diagnosis and details of consultations before reaching diagnosis were noted. The qualification of physician making diagnosis of DDH was also recorded to have an indirect idea about awareness of this pathology among various healthcare professionals. Time interval between first consultation and diagnosis of DDH was calculated and reason for a delay was asked. After diagnosis, the age at definitive treatment was inquired and time interval between diagnosis and treatment was calculated. Any reason for delay in treatment after diagnosis was noted. All possible reasons from birth of child to definitive treatment were grouped as physician-related and family/social factors. In case of an unreliable informant, further clarification from a more reliable one was sought telephonically.

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel 2016 and analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative variables, such as age at diagnosis, treatment and at the time of interview was summarised as mean. Qualitative variables, i.e. gender, residence, laterality, socioeconomic status, weeks of gestation, mode of delivery, presentation, place of delivery, perinatal complications, associated congenital anomalies and details of the physicians were presented as numbers and percentages. The association of symptoms with laterality was examined with Chi-square test. Pearson’s correlation test was used to find the correlation between different variables and significant level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Fifty four children with typical DDH satisfying the inclusion criteria were included in this study (Table I). There were 21 males and 33 females with mean age of 9.1 yr at interview (range: 18 months-20 yr). Thirty nine participants belonged to middle or high socioeconomic strata, with a stable income, whereas 15 had financial constraints. Thirty seven had unilateral involvement with affection of right hip in 20 and left hip in 17 cases, while 17 had bilateral involvement. The details of perinatal period are mentioned in Table II. Forty five children (83.3%) were born at full term whereas nine (16.6%) were preterm deliveries. Forty nine children (90.7%) were born in hospital receiving institutional attention in perinatal period whereas five (9.6%) were delivered at home. In the immediate postnatal period, 46 children were attended by one or more physicians. Paediatricians and gynaecologists were the most common medical professionals attending the newborns; 24 (44.4%) and 15 (27.7%) respectively. Seven newborns with perinatal complications and other associated anomalies were attended by more than one physician. This included general practitioners, physiotherapists and specialists such as paediatrician, gynaecologist, orthopaedician, paediatric surgeon, cardiovascular thoracic surgeon, neurosurgeon and ophthalmologist. Eight newborns were not attended by any physician. This included five babies delivered at home and three at a hospital who were attended by a staff nurse. While 50 children had an uneventful perinatal period, four had perinatal complications. Nine had another associated congenital anomaly. History of neonatal sepsis was not reported in any patient. Later, all patients had at least one visit to the paediatrician for routine check-up and immunization before diagnosis of DDH.

| Variable | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of children | 54 |

| Mean age | 9.1 yr |

| Gender | |

| Male | 21 (38.8) |

| Female | 33 (61.1) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 41 (75.9) |

| Rural | 13 (24.1) |

| Unilateral | 37 (68.5) |

| Right | 20 |

| Left | 17 |

| Bilateral | 17 (31.4) |

| Socioeconomic strata | |

| Poor | 15 (27.7) |

| Middle/high | 39 (72.2) |

| Variable | Number of patients, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Weeks of gestation | ||

| Preterm | 9 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| Term | 45 (83.3) | |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Vaginal | 32 (59.2) | 0.166 |

| LSCS | 22 (40.7) | |

| Presentation | ||

| Vertex | 44 (81.4) | <0.001 |

| Breech | 10 (18.5) | |

| Place of delivery | ||

| Home | 05 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Hospital | 49 (90.7) | |

| Perinatal complications (n=4; 7.4%) | ||

| Oligohydramnios | 2 | |

| Femur shaft fracture | 1 | |

| Neonatal jaundice | 1 | |

| Associated congenital anomalies (n=9; 16.6%) | ||

| Congenital foot deformity | 3 | |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 | |

| Congenital hernia | 2 | |

| Congenital torticollis | 1 | |

| Congenital cataract | 1 |

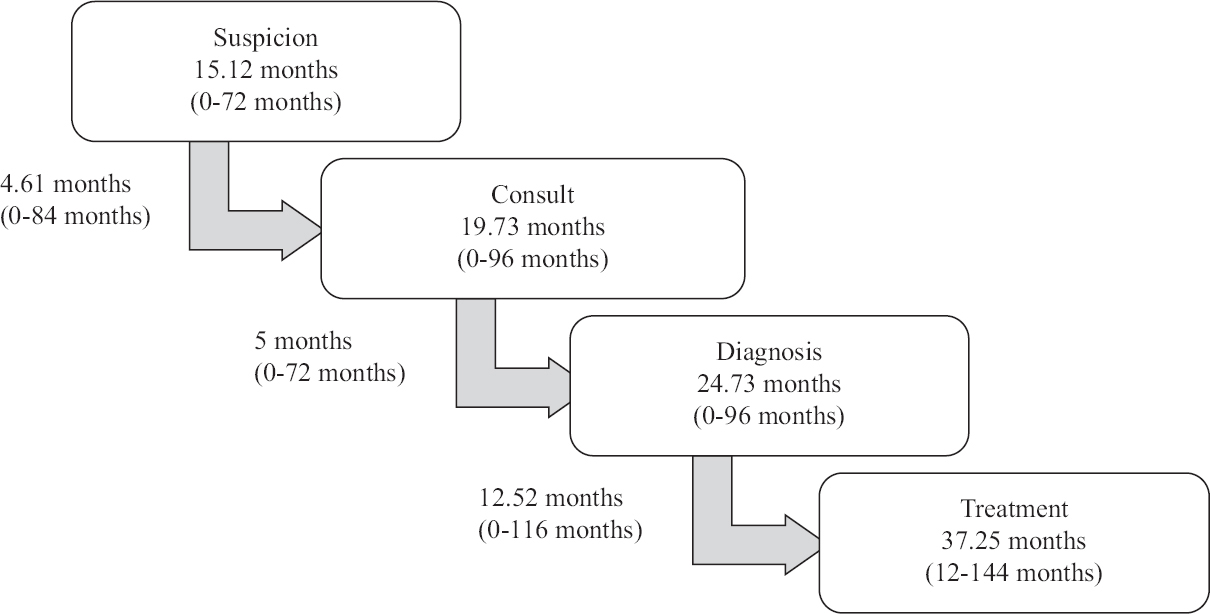

LSCS, lower segment caesarean section

Thirty one out of 54 (57.4%) children were diagnosed to have DDH between one and two years of age. Twenty one (38.8%) children reached diagnosis after two years, whereas only two cases were identified before one year of age. Symptoms suggestive of a hip abnormality were first noticed by family at a mean age of 15.12 months (range: 0-72 months; Fig. 1). In the majority, it happened when the child started walking and parents noticed an abnormal gait (Table III). The most common initial symptoms in unilateral involvement were limp and limb length discrepancy whereas, in bilateral involvement, delayed walking and gait abnormality (limping and waddling) caught the attention. Following that, there was a mean delay of 4.61 months (range: 0-84 months) between suspicion and first consultation with a healthcare professional. There was further mean delay of five months (range: 0-72 months) between first consultation and final diagnosis of a dislocated hip. Twenty four children went for more than one consultation mostly with registered medical practitioner [Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS), Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) and Bachelor of Homeopathic Medicine and Surgery (BHMS)] or a paediatrician before reaching a diagnosis. The mean age at diagnosis was 24.7 months (range: 0-96 months), and in 45 patients (83.3%), diagnosis was made by an orthopaedic surgeon.

- Average age value and average delay from suspicion to treatment.

| Symptom | Total (n=54), n (%) | Unilateral (n=37), n (%) | Bilateral (n=17), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limp* | 34 (62.9) | 27 (72.9) | 7 (41.1) |

| Limb length discrepancy** | 17 (31.4) | 16 (43.2) | 1 (5.8) |

| Delayed walking** | 16 (29.6) | 6 (16.2) | 10 (58.8) |

| Waddling** | 6 (11.1) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (29.4) |

| Abnormal positioning of lower limb | 6 (11.1) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (11.7) |

| Difficulty in sitting and/or squatting | 5 (9.2) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (11.7) |

| Frequent falls | 6 (11.1) | 4 (10.8) | 2 (11.7) |

| Increased lumbar lordosis** | 5 (9.2) | 0 | 5 (29.4) |

| Hip pain | 2 (3.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (5.8) |

| Restriction of abduction | 1 (1.8) | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

| Low back pain | 1 (1.8) | 1 (2.7) | 0 |

P *<0.05, **<0.01

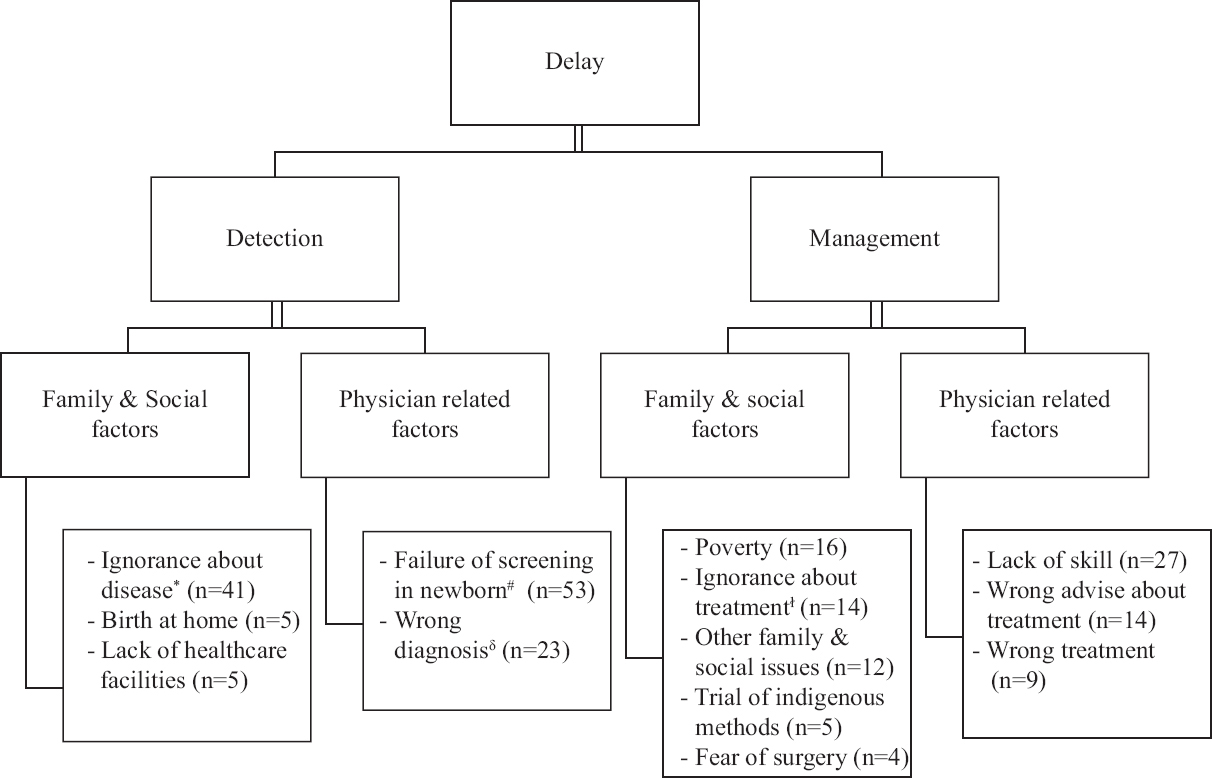

Definitive treatment of DDH was further delayed due to a number of reasons, as shown in Figure 2. Twenty one out of 38 (38.8%) children received treatment after two years of age. Seventeen were treated between one and two years, while 16 children did not receive the definitive treatment till the time of interview conducted during the present study. Two cases, despite being diagnosed during infancy, received treatment at 14 and 30 months, respectively. The mean age at definitive treatment was 37.3 months (range: 12-132 months) with an average delay of 12.5 months from diagnosis and 22.1 months from initial suspicion.

Seven children were managed by adductor tenotomy, closed reduction and hip spica, 30 by open reduction of hip with or without femoral and pelvic osteotomy and one by pelvic support osteotomy. Sixteen children had not undergone any definitive treatment at the time of interview. Satisfactory results (Severin type 1 and 2) were noted in two patients (28.5%) undergoing closed reduction and in 24 patients (80%) undergoing open reduction. Eight children needed further intervention in the form of revision open reduction in six, limb lengthening in one and open arthrolysis in one patient.

The physician related factors contributed to 55.2 per cent, whereas family and social factors together were responsible for 44.7 per cent reasons for overall delay. More than one reason was observed in many participants with both physician and family issues contributing for delay. Delay in diagnosis was the most common problem and was found in 52 (96.2%) children. DDH was missed despite patients visiting a paediatrician prior to diagnosis. Furthermore, once diagnosed, 27 (50%) children were referred to a higher centre for definitive treatment. This included 18 referred by an orthopaedic surgeon. Twenty (37%) children started seeking treatment within six months of diagnosis, showing compliance on their part. In the remaining 34 children, treatment was delayed due to a variety of reasons, as shown in Figure 2. Definitive treatment was deferred in two patients despite being diagnosed within six months of age. Both were advised surgery at a later date and were already of walking age when they presented to us. In eight children, parents were initially against surgery and looked for non-surgical options. They were either not convinced about surgery by the previous orthopaedic surgeon or were scared of the complications of surgery. Both these factors led the parents to shy away from surgery or seek second opinion, sometimes multiple, causing further delay in treatment. Other causes of delay were economic problem (16 children), family function or disturbances (12 children), waiting for school vacation (3 children) and other logistic issues.

- Various causes of delay in the DDH management pathway. *No suspicion by parents until child started walking. ꬷDelay of greater than or equal to six months between suspicion and first consult. #DDH not diagnosed at birth in hospital deliveries. δDDH not diagnosed at first consult. DDH, developmental dysplasia of hip

Discussion

With an incidence of about 1-2/1000 live births, between 25,000-50,000 babies are expected to be born with DDH in India every year10. Even though complete data regarding the total number of cases are not available, certainly many may be missed at birth. The causes of late-presenting DDH can be broadly classified into diagnostic delays and treatment delays. Treatment delays refer to delay in receiving appropriate treatment after the diagnosis was made. Both can be further split into physician-related, family and social factors.

In this study, the causes for late diagnosis were primarily physician related. The majority of children (90.7%) were born in hospital and were attended by one or more physicians in the neonatal period. Whether the clinical signs were missed by the attending physician or whether signs were not evident in these cases remained unclear. One may attribute it to either lack of adequate training among clinicians to screen for DDH or children missing the neonatal screening. However, it should be noted that even frank hip dislocation in newborns can have subtle or no clinical finding11. They may lack traditional risk factors for DDH and may not attract attention of the attending physician towards a possible hip pathology5,6,12. Similarly, instead of dislocation, they can have an acetabular dysplasia or subluxation which may not be detected on physical examination13. Late-onset dysplasia is also reported in literature14. Moreover, Ortolani and Barlow manoeuvres may not detect an already dislocated, irreducible hip5,15. Even experienced paediatric orthopaedic surgeons with special interest in DDH on occasions may struggle to detect a dislocated hip in a newborn11. Even if all clinical tests for screening of DDH are put together, the sensitivity and specificity remain only 63 and 58 per cent, respectively16. Thus, newborns who are cleared after a clinical screening may present later with a hip dislocation, and it is not always due to an inadequate clinical examination at birth. Poor parental awareness about the abnormality and inaction on their part is another contributing factor. This can be noted by the fact that there was an average delay of 4.6 months (0-84 months) between first suspicion by parents about the abnormality and consulting a doctor. Furthermore, there was an average delay of 22.1 months between suspicion and final treatment.

Even after diagnosis, the physician-related reasons contributed to delay in definitive treatment. We observed that parents were frequently misguided about indications for surgical treatment, right age at surgery, success of conservative and indigenous methods and complications of open surgery. In our study, 27 patients (50%) were referred to a higher centre for definitive management due to lack of skill and/or resources which added to further delay. In nine children, parents were hesitant to proceed with surgical treatment and kept trying for multiple opinions and non-surgical treatment options. When left untreated, incidence of high hip dislocation and avascular necrosis of femoral head increases, thereby producing significant disability in the long run15. Both the age at treatment and the severity of disease are important prognostic factors determining final outcome8,17. Moreover, delay increases the cost and overall burden on healthcare facilities of a country. We observed a similar trend with 76 per cent of our patients undergoing open surgery eventually (Fig. 3), one fourth of whom needed further intervention in the form of revision open reduction. Thus, early diagnosis of DDH is of utmost importance as it can be managed safely and effectively in a much simpler way.

- Effect of age of patient on the type of surgical intervention. CR, closed reduction; OR, open reduction; VDRO, varus derotation osteotomy

Early detection of DDH requires a holistic approach with combination of risk factor assessment, clinical examination and imaging studies. A knowledge of perinatal risk factors and clinical signs associated with neonatal DDH can forewarn the attending physician about its possibility, thereby reducing the incidence of late-diagnosed DDH. Previous studies reported greater incidence of late presentation in female child, deliveries conducted at rural hospitals, low birth weight (<2500 g) and when children were discharged early (less than four days) after birth11,18. Greater incidence of late diagnosis was also reported in second-born child, thereby reminding the clinicians that DDH could occur in any child18. Association with external factors such as swaddling, baby wrapping and carrying them with hips adducted and extended is well established19. Breech delivery and caesarean section, though associated with increased incidence of neonatal DDH, show lesser risk of late diagnosis as they are more likely to be examined by experienced paediatricians.

Clinical examination and ultrasonography (USG) are the two most commonly used methods for screening of DDH in neonatal period. However, they are known to have false-positive and false-negative results14,15. Arthrography and magnetic resonance imaging, although accurate in making diagnosis, are inappropriate for screening3. Clinical examination is easy to perform. Limited abduction of hip, asymmetrical thigh folds, limb length discrepancy and positive Barlow and Ortolani test are some of the helpful clinical signs to screen DDH in early life6. Many studies have supported the role of national clinical screening programmes in effectively reducing the incidence of missed DDH3,12,15. In Sweden, it helped in decreasing the age at detection and disease severity in addition to decreasing incidence of late-diagnosed DDH from 0.9 to 0.12/1000 live births15. Even paramedics such as physiotherapists and nurses can clinically diagnose DDH in neonates after appropriate training20. This is important in Indian context where we still do not have a national screening programme for DDH; as there is scarcity of specialized healthcare professionals, involvement of paramedics can be of great help. However, it must be emphasized that experience and awareness of examiner is the key to success of such programmes.

USG, on the other hand, is more effective with higher sensitivity. Countries such as Austria and Germany have adopted universal USG screening of hip in all newborns and reported negligible incidence of late-diagnosed DDH21,22. Notably it is costly, needs equipment and specially trained radiologist, is not readily available and can lead to both overdiagnosis and overtreatment5. Furthermore, many neonatal hip instabilities detected on USG resolve spontaneously with time23. Due to these arguments, selective USG screening of newborns with risk factors of DDH and for those with an inconclusive physical examination has been recommended and instituted in some countries. However, a similar incidence of late-diagnosed DDH after introduction of the national selective USG screening programme had been reported in some studies from England and Australia17,24. Besides, a recent Cochrane review found that both ultrasound strategies failed to improve clinical outcomes including late-diagnosed DDH and surgery25.

To balance the cost-effectiveness, the American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on DDH proposed that all newborns should be screened clinically and those with positive findings (positive Barlow and Ortolani test) should be referred to an orthopaedician3. When examination is inconclusive, clinical examination should be repeated after two weeks and those with positive findings or with risk factors for DDH should be referred. Rebello and Joseph4 devised a modified strategy for India which was effective despite logistic problems. They proposed clinical screening of all babies born in hospitals or brought to health centres for immunization. It can be done by obstetrician, paediatrician or orthopaedician depending on their availability. In case of a dislocatable hip, patients should be reviewed at two and six weeks. Treatment should be started immediately for dislocated hips and for dislocatable hips whose regular follow up cannot be ensured. However, despite combining clinical neonatal screening, use of selective USG screening and a 6-8 wk check, Talbot et al26 reported late presentations and hence advocated more screening examination down the line. Various strategies to reduce the detection and treatment delay are summarized in Table IV3,4,12,15,18,20,26-34.

| Diagnostic delays | Treatment delays |

|---|---|

| Strategies for physician factors | Strategies for physician factors |

| Universal clinical screening and selective USG screening for neonates followed by repeated hip check-ups until walking age. (it can be combined with universal immunization programme)4,26,27 To develop national screening guidelines for DDH in India4,27,28 Screenings to be done by experienced clinicians wherever possible15,26 Continued medical education for healthcare providers. Online education modules and hands-on training for hip screening18,30 Greater awareness of the problem among other specialities beyond paediatric and orthopaedic communities18 Inclusion of paramedics and midwives in screening for DDH in remote areas through special training4,20 Promotion of healthy hip swaddling19,31 |

Referral to orthopaedics for confirmed DDH and inconclusive screening3,4 More training and fellowship opportunities for orthopaedic surgeons to manage DDH effectively30,33 |

| Strategies for family factors | Strategies for family factors |

| To increase awareness about the disease and need for early detection and management through television, social media, posters, printouts and other methods of mass communication. Issuing self-check guides for parents containing risk factors and clinical signs of DDH12,18,32 To improve the healthcare resources. Tax-funded visits of all children at child healthcare centres33 Promoting healthy hip habits: To avoid swaddling, wrapping and other activities which brings hip in adduction and extension. Advise for healthy hip swaddling. Issuing a list of healthy hip early child care products19,31 |

To increase awareness about the prognosis and harmful effects of delayed treatment4,30,34 Web-based support groups29,30,33 To improve the healthcare resources33 Involvement of NGO: Organizing surgical camps and supporting treatment for those with financial constraints29,33,34 |

DDH, developmental dysplasia of hip; USG, ultrasonography; NGO, non-government organizations

The study is not without limitations. Firstly, this study is based on the patients seen at a tertiary referral centre and at a specialized paediatric orthopaedic clinic. The data from this small sample study may not reflect the national scenario. Furthermore, unlike in the present study, a fairly large number of children in parts of India are born at home in the absence of expert supervision. Hence, patients in our study may not be the exact representative of real population. Considering the fact that our patient population had better economic and educational status, the real situation could be even grimmer. Similarly, few centres/areas in country have a dedicated screening programme for DDH, and hence, the results of the current study may not be a reflection of practice in the rest of the country. The interview was not standardized and could be considered a limitation. Another important limitation of the present study is recall bias. Patients can very easily forget, get confused or readily blame doctors.

The findings of the present study suggest that the late presentation of DDH in walking age is not rarely encountered in a developing country. Reasons include delay in diagnosing DDH as well as delay in appropriate treatment after diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis is the most common reason for late presentation. Causes of late diagnosis are primarily due to failure or inadequacy of hip screening at birth by the attending physician, dysplasia with late dislocation and home deliveries with a lack of awareness among parents and of neonatal screening of the hips.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- The prevalence of dislocation in developmental dysplasia of the hip in Britain over the past thousand years. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:890-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2000;105:896-905.

- [Google Scholar]

- Late presentation of developmental dysplasia of the hip in children from southwest India –Will screening help? Indian J Orthop. 2003;37:210-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical examination versus ultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop. 2008;32:415-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of selected risk factors in developmental dysplasia of the hip: An observational study. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:692-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of Dega acetabuloplasty and Salter innominate osteotomy on acetabular remodeling monitored by the acetabular index in walking DDH patients between 2 and 6 years of age: Short- to middle-term follow-up. J Child Orthop. 2012;6:471-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital dislocation of the hip: Early and late diagnosis and management compared. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:407-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. National ethical guidelines for biomedical and health research involving human participants. Available from: https://www.icmr.nic.in/guidelines/ICMR_Ethical_Guidelines_2017.pdf

- Hip instability in newborns in an urban community. Natl Med J India. 1992;5:269-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Even experts can be fooled: Reliability of clinical examination for diagnosing hip dislocations in newborns. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40:408-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why is congenital dislocation of the hip still missed?Analysis of 96,891 infants screened in Malmö1956-1987. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62:87-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effectiveness of a programme for neonatal hip screening over a period of 40 years: A follow-up of the New Plymouth experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:245-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does late hip dysplasia occur after normal ultrasound screening in breech babies? J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:187-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of late-diagnosed hip dislocation after universal clinical screening in Sweden. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914779.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity and diagnostic bias in the clinical screening for congenital dysplasia of the hip. Acta Orthop Belg. 1994;60:315-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fifty-year follow-up of late-detected hip dislocation: Clinical and radiographic outcomes for seventy-one patients treated with traction to obtain gradual closed reduction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increase in late diagnosed developmental dysplasia of the hip in South Australia: Risk factors, proposed solutions. Med J Aust. 2016;204:240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Swaddling and hip dysplasia: An orthopaedic perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:5-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for congenital dislocation of the hip by physiotherapists. Results of a ten-year study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:458-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term results of a nationwide general ultrasound screening system for developmental disorders of the hip: The Austrian hip screening program. J Child Orthop. 2014;8:3-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of ultrasound screening on the rate of first operative procedures for developmental hip dysplasia in Germany. Lancet. 2003;362:1883-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of hip abnormalities detected by ultrasound in clinically normal newborns: A 6-8 year radiographic follow-up study of 93 children. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:335-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- What is the incidence of late detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip in England?: A 26-year national study of children diagnosed after the age of one. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:281-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane review: Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8:11-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Late presentation of developmental dysplasia of the hip: A 15-year observational study. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:1250-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preventive orthopaedics;screening for DDH. In: Johari AN, Luk KDK, Waddell J, eds. Current progress in orthopaedics 1. Mumbai: TreeLife Media (A Div of Kothari Medical); 2014. p. :95-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of newborns and infants for developmental dysplasia of the hip: A systematic review. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:1388-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why the time is ripe for India to develop a national DDH screening programme. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:1355-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence, diagnosis, and treatment practices of developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH) in India: A scoping systematic review. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:1428-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Swaddling practices in an Indian institution: Are they hip-safe?A survey of paediatricians, nurses and caregivers. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:147-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors and diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of hip in children. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2012;3:10-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip: An examination of care practices of orthopaedic surgeons in India. Indian J Orthop. 2021;55:158-68.

- [Google Scholar]