Translate this page into:

An integrated multidisciplinary model of care for addressing comorbidities beyond reproductive health among women with polycystic ovary syndrome in India

For correspondence: Dr Beena Nitin Joshi, Department of Operational Research, ICMR - National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health, Jehangir Merwanji Street, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, Maharashtra, India e-mail: joshib@nirrch.res.in

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is becoming an area of global and national health concern. It requires a life cycle approach from adolescence to menopause. To comprehensively address the wide spectrum of this disorder, a multidisciplinary model of care was established for women with PCOS in a government setting in India with an objective to screen and manage multifaceted manifestations of PCOS and to diagnose and treat associated comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, dermatologic manifestations and psychological issues.

Methods:

A model of integrated multidisciplinary PCOS clinic was implemented for services and research at ICMR-National Institute for Research in Reproductive and Child Health (NIRRCH), Mumbai Maharashtra, India. This is a one-stop holistic centre for managing menstrual, cosmetic, infertility, obesity, metabolic and psychological concerns of women affected with PCOS. Two hundred and twenty six women diagnosed with PCOS using the Rotterdam criteria were screened for metabolic comorbidities with anthropometry, ultrasonography, hormonal and biochemical tests and for psychological problems. Analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0.

Results:

Mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.1 kg/m2, higher for Asians. Hirsutism was observed in 53.6 per cent of women. Metabolic syndrome was seen among 35.3 per cent and non-alcoholic fatty liver in 18.3 per cent. Psychological issues such as anxiety and depression were identified in majority of the women 31.4 per cent of women could achieve pregnancy at the end of one year of multidisciplinary management.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The results of the present study suggest that an integrated multidisciplinary approach led to the early identification and treatment of comorbidities of PCOS, especially metabolic syndrome. There is hence an urgent need to implement multidisciplinary PCOS clinics in government health facilities.

Keywords

Comorbidities

integrated

metabolic syndrome

multidisciplinary model

polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most prevalent endocrine disorder among females with estimates ranging from 2.2 per cent to as high as 26 per cent1–4. With long-term metabolic and health-related comorbidities, PCOS is becoming an area of national as well as global concern. PCOS affects different stages of a woman’s life from adolescence to menopause and hence needs a life cycle approach.

Other metabolic abnormalities that are associated with PCOS include obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, glucose intolerance and insulin resistance which confer an increased long-term cardiovascular risk and other consequences such as type II diabetes mellitus5 . Women with PCOS are reportedly three times more prove endometrial cancer compared to women without it6.

Therapy should focus on the short-term as well as long-term reproductive, metabolic, cosmetic and psychological aspects of the condition along with counselling of the family and caregivers to provide social support7. In the long run, PCOS has an enormous burden on families, medical systems and health economies.

Women with PCOS primarily present with varied symptoms to general physicians who may treat symptoms without addressing the underlying pathology, so referral to various specialties is required. This can lead to incomplete management and temporary reversal of symptoms. Despite international evidence-based guidelines recommending integrated multidisciplinary services, current clinical services do not address the diverse needs of these women. Integrated multidisciplinary PCOS clinics with holistic care under one roof for weight reduction, nutrition, cosmetic and psychological issues are required to improve overall health, patient adherence and to combat the rising burden of PCOS and non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Such an approach can serve as an opportunistic window for screening and treating comorbidities beyond reproductive health at an early age. Hence to address PCOS holistically, a multidisciplinary model of care for PCOS was established with the objectives to screen and manage multifaceted manifestations of PCOS and to diagnose and treat associated comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, dermatologic manifestations and psychological issues.

Material & Methods

This was a descriptive observational study pertaining to the process documentation of the establishment of a model of care of an integrated multidisciplinary PCOS clinic at Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-National Institute for Research in Reproductive and Child Health (NIRRCH), Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Furthermore, this study retrospectively analysed the profile of women with PCOS who attended the clinic, including associated comorbidities and metabolic derangements during June 2016 till December 2018. Permission for publication of the retrospective data with waiver of consent was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee as the participants were deidentified.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The diagnosis of PCOS was based on the 2003 Rotterdam criteria8: (i) Oligo- or anovulation, (ii) Biochemical and/or clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism, and (iii) Ultrasound evidence of polycystic ovaries. The presence of at least two out of the above-listed three criteria defined a case of PCOS. Exclusion of other hormonal conditions such as hypothyroidism, hyperprolactinaemia and adrenal hyperplasia was done to make the diagnosis of PCOS. Patients already on drugs such as metformin and oral contraceptives were excluded for blood investigations to have treatment-naive participants. Furthermore, women with high follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), low anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) and low luteinizing hormone (LH) were excluded from the analysis.

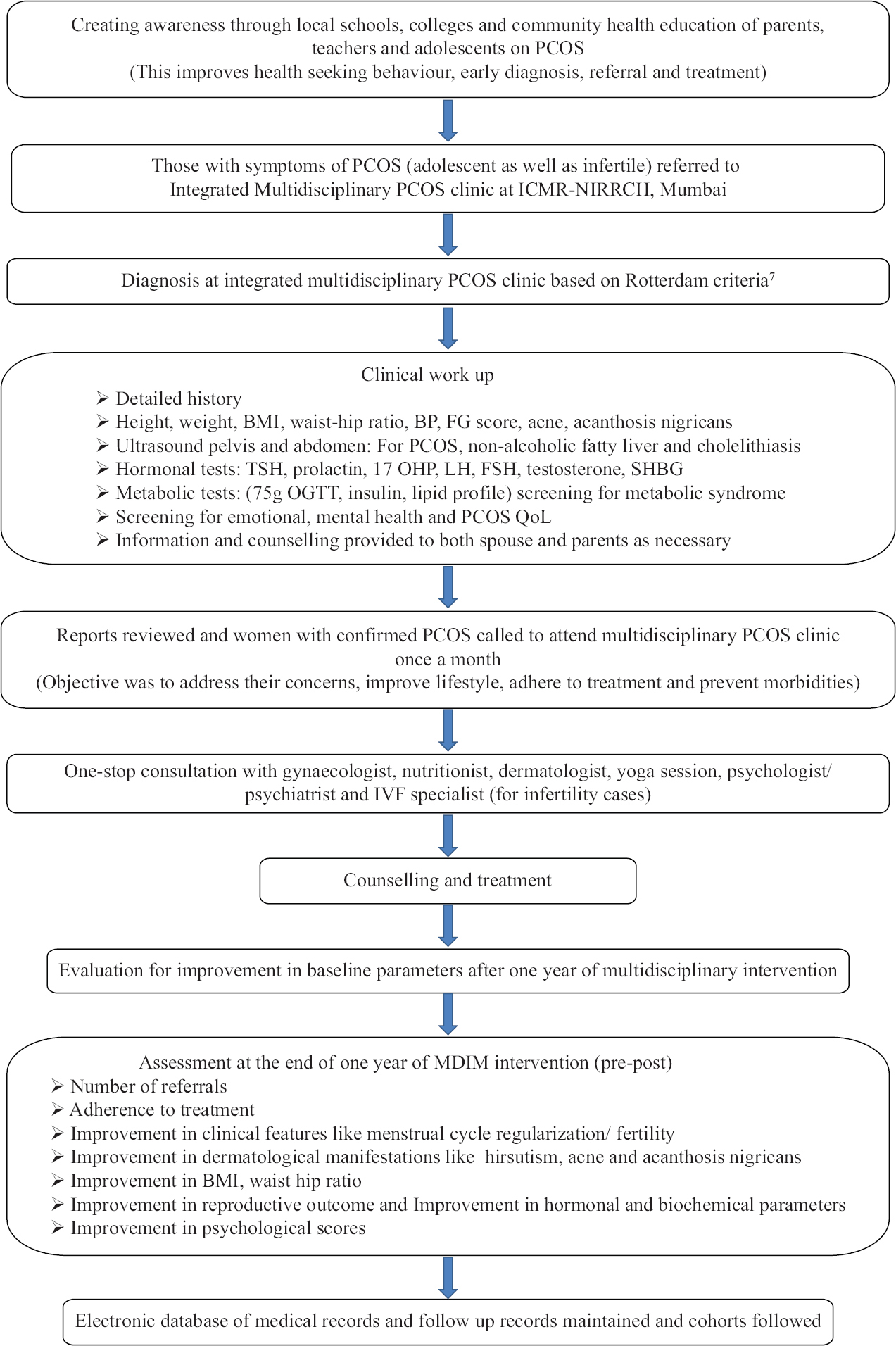

Process of establishing the clinic and its activities: The clinic was financially supported by the intramural grant of the ICMR-NIRRCH, Mumbai. A multidisciplinary team of specialist doctors consisting of a gynaecologist, infertility specialist, dermatologist, psychiatrist, nutritionist, yoga expert and counsellor were available to provide multidisciplinary management to women diagnosed with PCOS. The schematic representation of integrated multidisciplinary model of care for PCOS is shown in Figure 1.

- Integrated Multidisciplinary Model of care for PCOS at ICMR-NIRRCH, Mumbai, India. PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; QoL, quality of life

To raise awareness about the clinic and generate demand for services, several awareness activities were organised originally as part of various institutional programmes by the host institute in schools and colleges in the nearby vicinity. Adolescent and young girls, parents and teachers were sensitised on PCOS signs, symptoms, long term complications and available treatment, with a lot of emphasis on following healthy lifestyle, early diagnosis and adherence to treatment. General medical practitioners and healthcare providers in municipal run health facilities in the nearby locality were sensitised through CME (continued medical education) sessions. Awareness about the clinic was also integrated during any other community based programmes of the institute and through the existing Family Welfare clinics of the institute in the nearby vicinity.

Women with PCOS were managed on a regular basis and once in a month an integrated multidisciplinary clinic was conducted. Yoga sessions were held as a group activity on the monthly clinic day and women were taught how to practice the specific asanas at home.

A detailed case record form was developed with a digital version. Personal and medical history was noted in the designed case record form. Anthropometry, blood investigations and pelvic and abdominal ultrasonography were done to diagnose the cases based on the Rotterdam criteria8. Once the diagnosis of PCOS was made, the women were then counselled about the condition and the need for an integrated multidisciplinary management. They were also screened for metabolic comorbidities with biochemical tests. Standard anthropometric measurements were taken (height, weight, waist and hip circumference, waist–hip ratio). Hirsutism was quantified with the modified Ferriman-Gallwey score. Clinical signs of oily skin, acne and alopecia and acanthosis nigricans were noted.

Laboratory investigations: After 8 h of overnight fast, basal blood samples in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle were taken for the hormonal tests such as thyroid-stimulating hormone total testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, AMH, FSH, LH and vitamin D 25(OH)D. Metabolic tests such as glucose, total cholesterol, high-density and low-density lipoproteins and triglycerides determinations were done. All participants were tested for their fasting glucose and with 75 g glucose tolerance test (GTT). Insulin resistance was estimated using the Homeostatic Model of Assessment-Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR)9. Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed as per the modified American Heart Association (AHA)/National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Adult Treatment Panel III (2005) criteria10,11. Ultrasound examination of the pelvis and abdomen was done to confirm polycystic ovaries and non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL). Psychological status among these women was clinically assessed by the counsellors for obvious anxiety or depression.

Main outcome measures: Percentage of women diagnosed with PCOS, their varied clinical presentations and dermatological manifestations such as hirsutism, acanthosis, acne, oily skin, psychological issues like anxiety/depression and complications/comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, NAFL, impaired fasting glucose (IFG), impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) were noted.

Statistical analysis: Data were considered for analysis of anthropometric, ultrasound, hormonal, biochemical profile and psychological parameters of women with PCOS using the statistical package SPSS (version 19.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data were summarized as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as means with standard deviations.

Results

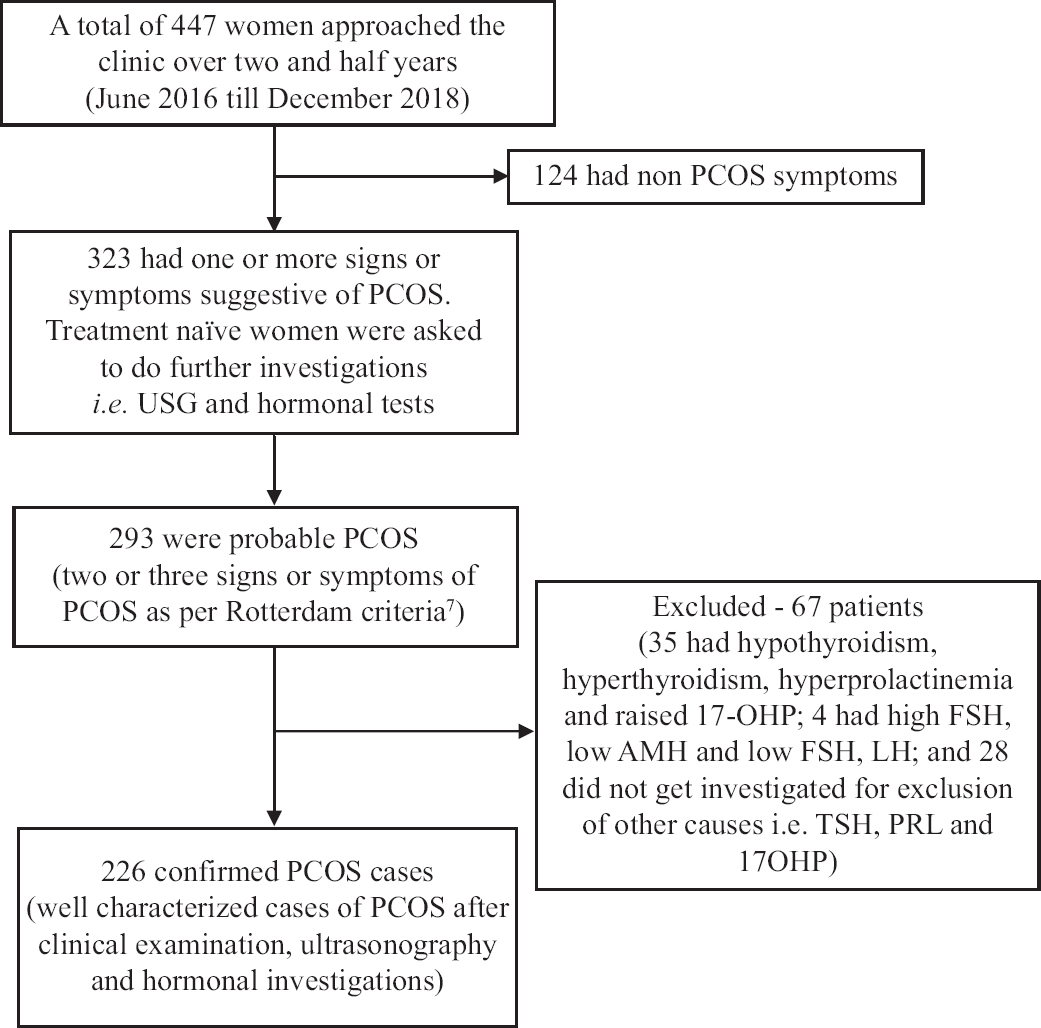

Data of all women attending the intergrated PCOS clinic from June 2016 to December 2018 (sampling frame) were assessed to finally arrive at 226 women with confirmed PCOS (Fig. 2).

- Flowchart for selection of cases of PCOS. PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome

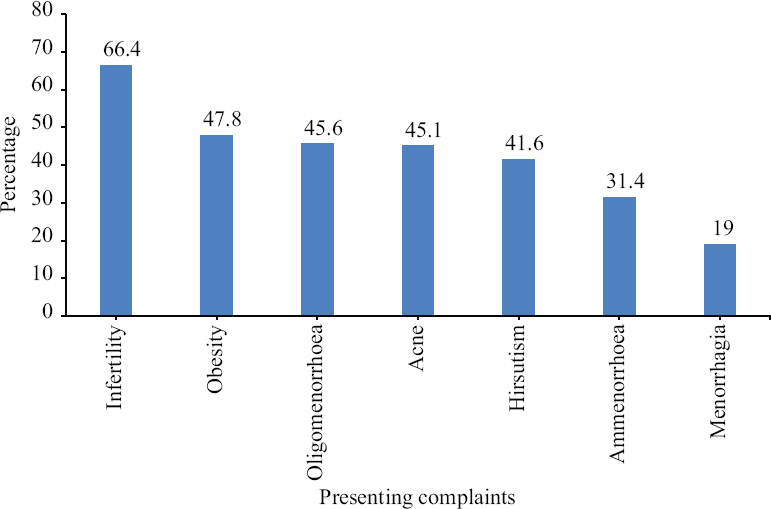

Retrospective analysis of women with PCOS who attended the clinic including associated comorbidities and metabolic derangements: The mean age of the clinic attendees was 26.27±4.9 yr. Majority of the women (75.2%) were married of which 66.4 per cent sought treatment for infertility. Twenty three per cent of the clinic attendees were unmarried approaching the clinic mostly for menstrual irregularity like oligomenorrhoea. Majority of the women were educated with 45.6 per cent being graduates. Thirty six per cent of these women were working and 14.2 per cent were students. They had varied presenting complaints as shown in Figure 3. Furthermore, there was an overlap in the presenting complaints like a woman presenting with infertility had obesity, oligomenorrhoea and hirsutism and such combinations.

- Percentage distribution of presenting complaints of women with PCOS (n=226). PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome

A comprehensive screening for comorbidities and metabolic and hormonal derangements was undertaken. Details of anthropometric, sonographic hormonal and metabolic parameters of women with PCOS attending multidisciplinary PCOS clinics are described in Tables I and II. Findings revealed that the mean BMI was 26.15 (SD±05.05), which is obese for Asian standards12 and also a higher mean waist–hip ratio of 0.85 (SD±0.1). The mean AMH level was high at 7.6 (SD±4.3), mean free androgen index (FAI) was high at 5.39 (SD±3.54), with 48.8 per cent women having biochemical hyperandrogenaemia (FAI > 4.59). Mean HOMA-IR was 3.9 (SD±3.5). Sixty seven per cent women had insulin resistance (HOMA-IR> 2.5). Vitamin D deficiency was common, with the mean 25(OH) D level being 11.44 ng/ml (SD±8.18). The mean follicle number per ovary was more than 15 on ultrasonography.

| Variables | n | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric parameters | ||

| Age (yr) | 26.27±4.9 | |

| Height (cm) | 226 | 153.47±5.53 |

| Weight (kg) | 226 | 61.55±12.96 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 226 | 26.15±05.05 |

| Waist (cm) | 226 | 85.5±12.8 |

| WHR | 226 | 0.86±0.10 |

| Total fat % | 215 | 34.43±4.93 |

| Visceral fat % | 209 | 8.03±5.66 |

| Skeletal muscle % | 218 | 23.86±2.36 |

| Sonographic parameters | ||

| Right ovary volume (cm3) | 220 | 13.67±5.96 |

| Left ovary volume (cm3) | 217 | 12.39±5.9 |

| Right stromal thickness (mm) | 184 | 10.84±5.4 |

| Left stromal thickness (mm) | 181 | 9.96±4.7 |

| Follicle number per ovary (right) | 174 | 14.24±11.28 |

| Follicle number per ovary (left) | 171 | 14.40±10.7 |

| Follicle number per section (right) | 184 | 8.18±4.5 |

| Follicle number per section (left) | 181 | 8.14±4.2 |

BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-hip ratio; SD, standard deviation

| Variables | n | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal parameters | ||

| LH (mIU/ml) 2 | 224 | 11.44±8.12 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 225 | 6.45±1.7 |

| AMH (ng/ml) | 216 | 7.99±4.46 |

| Total testosterone (ng/dl) | 222 | 42.96±18.94 |

| SHBG nmol/l | 221 | 36.22±24.37 |

| Free androgen index (FAI) | 217 | 5.39±3.54 |

| 17 OH progesterone (ng/ml) | 226 | 1.2±0.72 |

| Prolactin (ng/ml) | 226 | 10.47±4.25 |

| TSH (uIU/ml) | 226 | 2.18±0.96 |

| Metabolic parameters | ||

| FG (mg/dl) | 225 | 95.74±18.02 |

| Fasting insulin (mIU/ml) | 217 | 16.11±12.03 |

| PGBS 75 g (mg/dl) | 225 | 107.44±37.76 |

| HOMA-IR | 217 | 3.90±3.5 |

| 25(OH) D (ng/ml) | 224 | 11.44±8.18 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 223 | 174±34.6 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 222 | 115.9±30.07 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 221 | 44.58±16.10 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 223 | 108.12±64.84 |

SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FG, fasting glucose; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model of assessment-insulin resistance; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; PGBS, post prandial blood sugar

Seventy two per cent of the women were overweight and obese (Fig. 4). Metabolic syndrome was seen among 35.3 per cent of women with PCOS. NAFL on ultrasound was seen among 18.3 per cent of women. Deranged metabolic parameters are described in Table III. All the women were advised lifestyle modification with diet and exercise in consultation with a nutritionist and yoga expert. The management was not restricted to the chief complaints alone, but a multidisciplinary approach was used to manage other comorbidities diagnosed during screening. Cosmetic issues as described in Table IV were appropriately addressed by the dermatologist. For women who were suspected to be anxious or depressed appropriate referrals were made to the team psychiatrist for further investigation and management.

- Percentage distribution of BMI among women with PCOS (n=226). BMI, body mass index; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome

| Parameters | n | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFG (FPG >=100, <126 in mg/dl) | 225 | 37 | 16.4 |

| IGT (PG >=140, <200 in mg/dl) | 225 | 24 | 10.7 |

| NIDDM (n=225) (FPG >=126, PG >=200 in mg/dl) | 225 | 8 | 3.6 |

| HDL-C <50 mg/dl | 220 | 173 | 78.3 |

| TG ≥150 mg/dl | 222 | 11 | 4.9 |

| WC ≥80 cm | 226 | 148 | 65.5 |

| BP ≥130/85 mm Hg | 226 | 33 | 15.0 |

| Metabolic syndrome as per modified AHA/NHLBI, ATP III criteria (3 out of 5 criteria present) | 220 | 64 | 35.3 |

| No criterion of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 22 | 9.7 |

| One criterion of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 48 | 21.2 |

| Two criteria of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 73 | 32.3 |

| Three criteria of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 60 | 26.5 |

| Four criteria of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 14 | 6.2 |

| Five criteria of metabolic syndrome present | 220 | 04 | 1.8 |

IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; NIDDM, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; WC, waist circumference; BP, blood pressure; AHA, American Heart Association; NHLBI, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; ATP, Adult Treatment Panel

| Dermatological manifestation | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Hirsutism | ||

| FG score >8 | 118 | 53.6 |

| Acanthosis | 23 | |

| Neck | 90 | 41.7 |

| Axilla | 118 | 54.4 |

| Groin | 130 | 59.4 |

| Acne on face | ||

| Mild | 82 | 37.3 |

| Moderate | 28 | 12.7 |

| Severe | 11 | 5 |

| Acne on back (n=219) | ||

| Mild | 35 | 16 |

| Moderate | 15 | 6.8 |

| Severe | 5 | 2.2 |

| Oily skin | ||

| Mild | 103 | 46.8 |

| Moderate | 69 | 31.4 |

| Severe | 3 | 1.4 |

FG, fasting glucose

Cohorts of adolescent and infertile women with PCOS were followed at the clinic with an integrated multidisciplinary approach with lifestyle modification programme of diet, exercise, yoga, counselling and pharmacotherapy.

Telephonic feedback was obtained from 155 women with PCOS. Following the multidisciplinary approach, the knowledge and awareness about treatment options were assessed. Seventy six per cent had informed knowledge about exercise and 77.1 per cent about nutrition and proper diet. One year following the multidisciplinary approach 83.8 per cent had adherence to medication, 52.3 per cent adhered to recommended diet, 46.5 per cent to exercise. Walking was the most common exercise practiced by 53.5 per cent. Sixty eight per cent women were convinced that lifestyle management helps in weight reduction and psychological well-being. Majority of the women were convinced about the benefits of multidisciplinary approach to achieve pregnancy. At the end of one year of multidisciplinary approach, 31.4 per cent women became pregnant out of which 22.5 per cent within six months and 77.5 per cent within one year.

Discussion

The PCOS cases are increasing not only among women with infertility but also among adolescents2. The present study highlights that early identification and treatment of PCOS needs an integrated multidisciplinary approach to address comorbidities like metabolic, cosmetic and psychological concerns holistically.

The comorbidities associated with PCOS extend beyond the reproductive system. PCOS is a more important risk factor than ethnicity or race for glucose intolerance in young women13. In the Indian population, there is a higher prevalence of glucose intolerance even at younger age in women with PCOS. Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) is reportedly high (36.3%) among young Indian women with PCOS14 . Glucose challenge test significantly improves the detection rate of IGT among Indian women with PCOS15. Our data also showed a high percentage (30.7%) of women with deranged laboratory tests of glucose metabolism such as fasting glucose, IGT and diabetes (Table III). Acanthosis, a surrogate marker of insulin resistance was evident in 23 per cent women. Insulin resistance (HOMAIR >2.5) was found in high percentage of young women (67%). PCOS reportedly further adds to the risk for the development of metabolic and cardiovascular abnormalities. The overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome among Indian women with PCOS was 37.5 per cent16. This study also showed that more than one-third of women with PCOS have metabolic syndrome emphasizing the need to screen them for pre-diabetic state and metabolic syndrome. Early initiation of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions can prevent long-term complications.

NAFL is the most common hepatic disorder and the leading cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis. A meta-analysis demonstrated that NAFL prevalence was significantly higher in patients with PCOS17,18. The present study also showed a higher prevalence of NAFL similar to other Indian studies19,20. For PCOS women who are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, it is important to do a screening ultrasound for NAFL and liver function tests to prevent further progression.

Psychiatric illness may also go undetected in a proportion of PCOS patients. Although the majority of patients exhibit subclinical levels of psychological disturbances, emotional distress together with obesity leads to large decrements in quality of life in PCOS21. A study on south Indian population revealed that 54 per cent of women with PCOS had increased psychological distress22. Psychological disturbances were high in the present study population probably due to added stress of infertility. This emphasizes the importance of screening of these women for psychological health and intervention by a psychologist to prevent the future burden of psychiatric morbidities.

Dermatological concerns are common in PCOS. A study demonstrated that among women with PCOS, 56 per cent had hirsutism, 53 per cent had acne, 23 per cent had acanthosis nigricans and 16 per cent had alopecia23. Similar observations were also made from the findings of the present study as summarized in Table IV. Cosmetic concerns adversely affect quality of life, especially among adolescents with PCOS. Addressing the cosmetic concerns with effective treatment of hirsutism, acne and acanthosis by a dermatologist is equally important in a multidisciplinary approach.

The most common cause of treatable infertility among young women is PCOS, and PCOS is the cause of anovulatory infertility in 70 per cent cases24. In women with PCOS, the reproductive outcome with infertility treatment is good with a cumulative live birth rate of approximately 70 per cent24. Pre-conception optimization of health status, judicious use of ovulation inducing agents and assisted reproduction techniques can further help to achieve better pregnancy rates among these women.

Opportunities of an integrated multidisciplinary approach are plenty as women get to be screened for comorbidities which could help them take measures to prevent long-term complications. Women also get an opportunity to seek specialist care as per their concerns. Pre-pregnancy optimization of the health status of women prepares them for safe pregnancy and motherhood. Psychological morbidities are considered a stigma and hence remain undiagnosed and untreated. The holistic approach provides a chance for early diagnosis and management of these morbidities. With minimal training, resources and teamwork, it is feasible to implement such a model of care in public health settings.

The major feedback of women for the multidisciplinary PCOS clinic intervention was that they were benefited to a great extent as they could get proper treatment from all concerned specialities under one roof. Altogether women were benefited from hormonal and metabolic blood investigations, ultrasound and lifestyle modification programme consisting of yoga and nutritional advice, which helped them in weight reduction. This coupled with the management of dermatological manifestations like hirsutism and acanthosis helped young girls to develop a positive body image. Most women reported that in addition to these benefits Yogic practice also helped them to cope with stress. Holistic management under one roof saves their travel time, logistics to consult different specialists. Health benefits included regularisation of menstrual cycles, weight reduction, adhering to treatment, achieving positive body image and improving fertility outcomes.

PCOS is a diagnosis of exclusion and involves identifying a syndrome using history, clinical examination, laboratory investigations and ultrasonography and this is time-consuming and resource-intensive. In this context there are several challenges faced during the implementation of this model. Working women have time constraints to do their hormonal investigations in the follicular phase and in the fasting state. If on prior medication, keeping them on a pill-free interval for hormonal investigations is also difficult. Furthermore, women often manage cosmetic problems with beauticians; hence, the assessment of clinical hyperandrogenism becomes difficult. The authors feel that the biggest challenge to the physician is describing the complexity of the disorder, which has no definite cure. Furthermore, lifestyle adherence needs support from family, which is beyond the control of the treating physician. Drugs also need long-term monitoring, especially combined oral contraceptive (COC) pills for risk of venous thromboembolism. Continuous motivation is also required to improve adherence to lifestyle modification. Long-term compliance mechanisms considering risk-benefit ratio also have to be inbuilt in such a model. Last but not least, a dedicated team investing time and effort with interdisciplinary communication is quint essential.

Globally, the concept of integrated management of PCOS is gaining ground. In Australia, the National PCOS Alliance comprises national leaders from research, clinical and community sectors with the aim to strengthen collaborations between these key groups to implement the multidisciplinary clinics in urban and rural areas25. The Alliance developed the only evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of PCOS, which is endorsed by the World Health Organization26. These guidelines emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach with medical specialists and allied health staff to deliver holistic care addressing the bio-psycho-social aspects of PCOS and highlight the importance in tailoring the management plan to address an individual patient’s needs. The University of California and San Francisco and the University of Pennsylvania also offer an integrated multidisciplinary approach for women with PCOS27. Currently, there are only two multidisciplinary PCOS treatment facilities that have published research regarding the outcomes of their clinics22,25. A patient satisfaction survey reported that a multidisciplinary, dedicated PCOS clinic was useful and that patients were happy with the results28. When treating a patient with PCOS it is important to focus on treating the patient’s initial needs while decreasing the risk of long-term risk factors. Symptoms will be better treated if the patient is treated by a variety of specialists all working together. The perceived benefits of multidisciplinary clinics globally include improved patient satisfaction, greater weight loss, improved body image and better management of PCOS from a holistic standpoint29.

An integrated multidisciplinary model addresses various comorbidities of women with PCOS beyond reproductive health and serves as a unique platform for evidence-based services and research on various aspects of PCOS30. Such a model of care is feasible in developing countries like India and replication and scaling up at tertiary care centres like medical colleges is recommended. Faculties from departments of gynaecology, dermatology, endocrinology, medicine, dietetics, psychiatry and community medicine need to work in an integrated manner. Once a month fixed day integrated clinic is a practical approach. A clear management algorithm must be made available in a capacity-building programme30,31.

One limitation of the study was that there was no control group since this was a process documentation and retrospective analysis of the data of the multidisciplinary PCOS clinic. Matched controls can be added for studies planned in the future from the clinic.

Overall, there is a need to develop linkages with national programmes on adolescent reproductive and sexual health, NCDs and wellness centres to facilitate an efficient diagnosis and management system of PCOS. Engagement of community and education system is important to create awareness among parents and teachers. Such a model will greatly contribute to reduce the economic burden of NCDs in the long run and improve quality of life of women with PCOS in developing countries.

Acknowledgment:

The authors acknowledge the mentorship provided by Dr Smita Mahale, Director ICMR-NIRRCH. The contribution of the Consultants of Multidisciplinary PCOS team (Drs Sukhpreet Patel, Vidya Kharkar, Ajita Nayak, Satish Pathak, Ms Shobha Udipi and Veena Yardi) and also the technical help provided by our staff nurse Ruhi Pednekar and Anamika Akula are acknowledged. The technical inputs from Drs Gazala Hasan and Dinesh Aahuja in manuscript preparation are also acknowledged.

Financial support & sponsorship: The study was supported by the intramural fund of ICMR-NIRRCH, Mumbai.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Geographical prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome as determined by region and race/ethnicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 20182589;15

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study of polycystic ovarian syndrome among adolescent and young girls in Mumbai, India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:317-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome: Prevalence and its correlates among adolescent girls. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2013;6:632-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome in Indian adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:223-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS):Long-term metabolic consequences. Metabolism. 2018;86:33-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the association between endometrial cancer and polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1327-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med. 2010;8:41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome:An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4565-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR):A better marker for evaluating insulin resistance than fasting insulin in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2017;27:123-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Consensus statement for diagnosis of obesity, abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome for Asian Indians and recommendations for physical activity, medical and surgical management. J Assoc Physicians India. 2009;57:163-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asian BMI criteria are better than WHO criteria in predicting Hypertension: A cross-sectional study from rural India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8:2095-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of glucose intolerance among adolescent and young women with polycystic ovary syndrome in India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2004;6:9-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral glucose tolerance test significantly impacts the prevalence of abnormal glucose tolerance among Indian women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Lessons from a large database of two tertiary care centers on the Indian subcontinent. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:194-201. e1-3

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome attending an infertility clinic in a tertiary care hospital in south India. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2012;5:26-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and polycystic ovary syndrome are associated by necessity rather than chance: A novel hepato-ovarian axis? Endocrine. 2016;51:211-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are women with polycystic ovarian syndrome at a high risk of non-alcoholic Fatty liver disease;a meta-analysis. Hepat Mon. 2014;14:e23235.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in South Asian women with polycystic ovary syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:7046-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5801-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychosocial aspects of women with polycystic ovary syndrome from south India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:945-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:1602-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Chances of Infertility in a Patient Presenting with PCOS in Childbearing Age. Saudi J Med. 2022;7:15-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: approach to clinical practice. Clinics. 2015;70:765-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Correlation Between Body Fat, Visceral Fat, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2017;15:304-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of adolescents presenting to a multidisciplinary clinic for polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23:7-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- UCSF multidisciplinary clinic for women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Available from: https://pcos.ucsf.edu/multidisciplinarycare

- A 2 year audit of the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) clinic at the Royal Berkshire Hospital. Endocr Abstr. 2005;9:79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional management in women with polycystic ovary syndrome:A review study. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11((Suppl 1)):S429-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- The current description and future need for multidisciplinary PCOS clinics. J Clin Med. 2018;7:395.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated model of care for polycystic ovary syndrome. Semin Reprod Med. 2018;36:86-94.

- [Google Scholar]