Translate this page into:

A comparative study on the anti-inflammatory effect of angiotensin-receptor blockers & statins on rheumatoid arthritis disease activity

For correspondence: Dr Ahmed H. Elabd, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tanta University, Tanta 31527, Egypt e-mail: drahmedh.elabd12@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Rheumatoid artherits (RA) is a refractory disease and the imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in favor of pro-inflammatory cytokines has been implicated in pathogenesis of RA. In this context, the aim of the present study was to compare the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of candesartan, an angiotensin-receptor blocker, and atorvastatin in RA patients.

Methods:

In this single-blinded parallel randomized placebo controlled study, the patients recruited between December 2017 and May 2018 were categorized into three groups: group 1 included 15 RA patients who served as control group and received traditional therapy (+ placebo); group 2 included 15 RA patients who received traditional therapy + candesartan (8 mg/day); and group 3 included 15 patients who received traditional therapy + atorvastatin (20 mg/day) for three months. Clinical status in RA patients was evaluated by Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and morning stiffness before and three months after treatment. All groups were subjected to biochemical analysis of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) and malondialdehyde (MDA) before and three months after treatment.

Results:

Both candesartan and atorvastatin treated groups showed significant decrease in serum levels IL-1β and TNF-α, acute-phase reactants (CRP and ESR), number of swollen joint and patient global assessment. This was also associated with improvement in disease activity and quality of life regarding DAS28 and HAQ-DI as compared to baseline data and the control group. Atorvastatin group showed significant decrease in the serum level of oxidative stress marker (MDA).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Both candesartan and atorvastatin showed anti-inflammatory effect and immunomodulatory effects leading to improvement in clinical status and disease activity in RA patients. However, atorvastatin was superior to candesartan through its anti-oxidant effect.

Keywords

Anti-inflammatory

atorvastatin

candesartan

inflammatory cytokines

MDA

rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory, systemic autoimmune disease affecting mostly the joints but often with systemic involvement, characterized by chronic inflammation and the progressive destruction of joints1. An imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in favour of the pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) or tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)] has been implicated in the pathogenesis of RA2. The balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is a potential therapeutic target in RA. Renin-angiotensin system is known to be involved in inflammation and immune responses of autoimmune disorders, including RA3. Angiotensin II activates angiotensin II type 1 receptors (AT1R), resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor Kappa B (NF-kB) activation leading to the production of various inflammatory cytokines45. AT1Rs are upregulated in the rheumatoid synovium and thus may be a novel therapeutic target and angiotensin II-receptor blockers (ARBs) may provide anti-inflammatory benefits6.

Statins are widely used as cholesterol-lowering agents and also have pleiotropic effects78, which encompass modification of endothelial function, plaque stability and thrombus formation. Statins act as immunomodulators and suppress T-cell activation, and decrease inducible major histocompatibility complex-class II (MHC-II) protein expression by interferon-γ on human endothelial cells and macrophages9. Statins also have anti-inflammatory properties that regulate leucocyte-endothelial cell adhesion, reduce nitric oxide (NO) production and decrease levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and IL-610. Therefore, the present study was aimed to compare the anti-inflammatory effect of candesartan and atorvastatin in RA patients, through evaluating their impact on inflammatory and oxidative stress markers including TNF-α, IL-1β, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and malondialdehyde (MDA). Furthermore, the clinical status and disease activity of RA patients were also assessed by including the number of swollen joints (NSJ), number of tender joints (NTJ) and morning stiffness with subsequent effect on the quality of life.

Material & Methods

All patients attended at the outpatient clinics of the Internal Medicine department (Rheumatology and Immunology Unit) and Physical Medicine, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation department in Menofia University Hospital, Menofia, Egypt, during December 2017 and May 2018, were enrolled in this study. The selection of patients was based on an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria 2010 for diagnosis of RA11.

Inclusion criteria included patients with moderate-to-high disease activity and their ages ranging from 18 to 65 yr. All patients received non-biological drugs, corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Pregnant and lactating females, patients with liver, renal impairment or any other inflammatory diseases were excluded. The patients treated with TNF-α or IL-1β antagonists were also excluded from the study to exclude the effect of these treatments on serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β.

The study protocol was approved by the Tanta University Research Ethical Committee, Tanta, Egypt, prior to enrolment of the patients and all participants gave their written informed consent (Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT03770702).

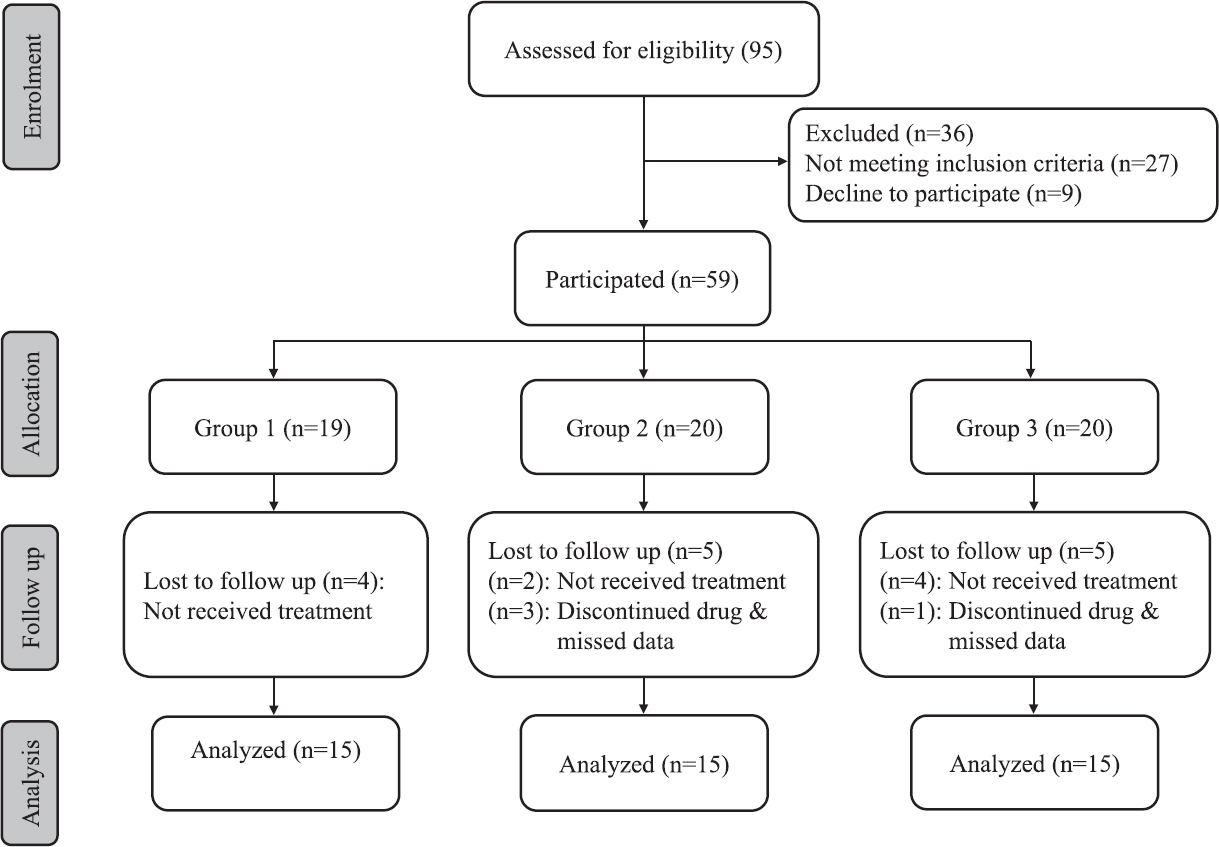

Study design: The study design was single blind parallel randomized placebo controlled study to compare anti-inflammatory effects of candesartan and atorvastatin in RA patients. Ninety five RA patients were randomly selected using sealed envelopes method from a total of 200 patients who attended the hospital. Fifty nine of the eligible patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and sub-classified into three parallel groups according to their associated medical condition. Out of the 59 eligible patients, only 45 patients completed the study. Fourteen patients did not receive treatment and were excluded from the analysis (Figure). Group 1 served as control group and patients received traditional therapy + placebo (n=15), group 2 patients received traditional therapy + candesartan, 8 mg/day (n=15). Group 3 patients received traditional therapy + atorvastatin, 20 mg/day (n=15) for three months. Medical history of the patients was taken, and demographic data were collected at baseline through a questionnaire. All patients were followed up weekly to ensure compliance to the treatment. Venous blood (5 ml) was drawn from each patient (after 10-12 h fasting) between 9 and 11 h before and after the treatment course; serum was separated after centrifugation, coded and stored at −80°C until analysis.

- Flowchart showing study design.

Methods

Physical and clinical examination: All patients were subjected to clinical examination to determine the number of tender and swollen joints. Pain of the joints was evaluated on the basis of the visual analogue scale. All patients were examined for extra-articular manifestation before and after treatment. The Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)12, was calculated using questionnaire (20 questions), and the patient's responses made on a scale from zero (no disability) to three (completely disabled). Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28)13, was calculated using the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), number of tender and swollen joints and patient global assessment (PGA). Remission was considered achieved if the DAS score was between 0 and <2.6. Low activity corresponded to 2.6 to <3.2. Moderate activity was between 3.2 and ≤5.1, while high activity was strictly >5.1.

Laboratory investigation and biochemical tests: TNF-α, IL-1β and MDA were assayed by ELISA kits (Shanghai Sunred Biological Technology Co., Ltd, China). Complete blood count was assayed by automated Cobas® e411 Haematology analyzer (Roche, Germany). Rheumatoid factor (RF) and CRP were assayed by Heales QR-100TM Protein Analyzer (Heales, China). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine (S.Cr) and lipid profile were assayed by fully automated Beckman Coulter/Olympus AU680 Chemistry Analyzer, Japan.

Statistical analysis: All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistical Package version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Fisher's exact test was used for statistical analysis of nominal data. Paired t test was used to assess any significant difference between each group at baseline and three months after treatment. The variances among groups are homogenous but different in their associated medical condition; therefore, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to assess any significant difference between three groups at baseline and three months after treatment. All data were presented as mean±standard deviation. The significance level was set at P values (P) <0.05.

Results

The three groups were matched for age, sex, disease duration and the RA treatment protocols as illustrated in Table I. The ANOVA test was used to compare clinical, laboratory and biochemical parameters between the three groups at baseline and three months after treatment (Table II). At baseline the three groups were significantly different in systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides (TGs), morning stiffness, CRP, and HAQ-DI. At three months after treatment TC, HDL, LDL, morning stiffness, ESR, and HAQ-DI were significantly different among the three groups (Table II).

| Parameters | Groups (n=15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (Control) | Group 2 (Candesartan) | Group 3 (Atorvastatin) | |

| Age (yr), mean±SD | 49.66±9.57 | 54.93±7.33 | 49.06±9.81 |

| Duration of disease (yr), mean±SD | 6.06±2.63 | 5.66±2.89 | 5.86±2.47 |

| Groups (n=15), n (%) | |||

| Group 1 (Control) | Group 2 (Candesartan) | Group 3 (Atorvastatin) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2 (13.33) | 1 (6.67) | 1 (6.67) |

| Female | 13 (86.67) | 14 (93.33) | 14 (93.33) |

| Treatment | |||

| Prednisolone | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 15 (100) |

| Diclofenac | 15 (100) | 15 (100) | 15 (100) |

| Methotrexate | 10 (66.67) | 10 (66.67) | 10 (66.67) |

| Leflunomide | 10 (66.67) | 10 (66.67) | 8 (53.33) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 10 (66.67) | 8 (53.33) | 11 (73.33) |

| Sulphasalazine | 2 (13.33) | 4 (26.67) | 3 (20) |

| Parameters | Group 1 (Control) (n=15) | Group 2 (Candesartan) (n=15) | Group 3 (Atorvastatin) (n=15) | ANOVA (P) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After three months | Baseline | After three months | Baseline | After three months | Baseline | After three months | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 122.3±19.4 | 123.0±17.0 | 157.6±7.0 | 133.3±7.9*** | 125.3±16.3 | 125.3±15.2 | <0.01 | NS |

| DBP (mmHg) | 72.00±9.02 | 72.66±9.42 | 92.33±2.58 | 79.00±6.03*** | 75.33±8.55 | 73.66±9.53 | <0.01 | NS |

| TC (mg/dl) | 182.9±12.1 | 177.4±19.7 | 173.8±16.7 | 173.8±19.1 | 194.8±16.9 | 133.4±15.0*** | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 49.0±9.9 | 52.6±10.4 | 59.2±14.8 | 60.6±13.1 | 50.6±8.9 | 64.2±11.4*** | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 90.9±16.1 | 89.0±13.1 | 86.8±13.5 | 85.5±10.5 | 98.0±21.9 | 74.0±12.2*** | NS | <0.01 |

| TGs (mg/dl) | 111.8±13.9 | 109.7±17.2 | 103.1±13.8 | 105.0±14.5 | 134.2±22.3 | 105.6±18.0*** | <0.01 | NS |

| Morning stiffness (min) | 41.6±16.4 | 36.7±16.9 | 65.3±17.2 | 51.0±15.8*** | 53.0±18.6 | 42.0±11.6** | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| RF (IU/ml) | 53.7±33.5 | 51.2±33.0 | 71.4±77.5 | 62.9±64.6 | 51.0±32.2 | 42.9±24.9** | NS | NS |

| ESR (mm/h) | 55.8±15.8 | 56.0±19.6 | 49.8±31.4 | 40.3±20.4* | 48.8±19.0 | 39.8±15.0** | NS | <0.05 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 26.3±25.7 | 28.5±26.5 | 46.6±29.3 | 39.9±26.2* | 26.6±17.5 | 21.1±13.5*** | <0.05 | NS |

| DAS28 | 4.71±0.52 | 4.83±0.56 | 5.50±1.19 | 4.95±0.75* | 4.97±0.92 | 4.46±0.79*** | NS | NS |

| HAQ-DI | 1.17±0.12 | 1.20±0.12 | 1.45±0.24 | 1.36±0.17* | 1.32±0.16 | 1.22±0.15*** | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| MDA (nmol/ml) | 22.8±11.7 | 21.7±13.9 | 17.0±23.0 | 12.7±17.4 | 20.7±15.8 | 12.9±10.9* | NS | NS |

| IL-1β (pg/ml) | 2147.7±591.2 | 2366.8±544.2 | 2695.6±1872.4 | 2033.6±1163.6* | 2308.5±1119.4 | 1861.8±873.8* | NS | NS |

| TNF-α (ng/ml) | 120.5±54.0 | 140.7±61.2 | 168.8±139.9 | 113.2±97.7* | 169.0±85.1 | 120.2±71.5* | NS | NS |

Values shown as mean±SD. P*<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001 compared to respective baseline. SD, standard deviation; ANOVA, analysis of variance; P, P-value; NS, not significant; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TGs, triglycerides; PGA, patient global health assessment; RF, rheumatoid factor; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, disease activity score 28; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; MDA, malondialdehyde; IL-1β, interleukin one beta; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha

Furthermore, ANOVA was used to compare the percentage of mean changes in clinical and biochemical parameters from baseline to the end of treatment between the three studied groups (Table III). The three groups were significantly different in the percentage of mean changes for CRP, DAS28, HAQ-DI, IL-1β and TNF-α levels from baseline to the end of the treatment.

| Per cent change in variables | Group 1 (n=15) | Group 2 (n=15) | Group 3 (n=15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morning stiffness (min) | 5.55 | −19.04 | −15.55 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 1.23 | −11.99 | −15.53 |

| CRP (mg/l)** | 10.11 | −12.33† | −15.28† |

| RF (IU/ml) | −4.667 | −7.663 | −9.599 |

| DAS28* | 3.00 | −7.67 | −9.69† |

| HAQ-DI* | 3.89 | −4.77 | −7.29† |

| MDA (nmol/ml) | 6.86 | 17.72 | −12.99 |

| IL-1β (pg/ml)* | 15.74 | −17.67† | −12.52 |

| TNF-α (ng/ml)** | 26.93 | −25.47† | −23.35† |

P*<0.05, **<0.01 (ANOVA); †P<0.05 compared to group 1 (post hoc test)

Both candesartan and atorvastatin treated groups (groups 2 and 3) showed significant decrease in serum levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and acute-phase reactants (CRP and ESR) as compared to baseline values. As compared to the base line, patients on atorvastatin showed significant decrease in RF and MDA levels, while patients on candesartan showed non-significant changes in these parameters (Table II).

The decrease in the serum level of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) was accompanied by significant improvement in physical and clinical parameters regarding PGA, number of tender joints (NSJ) and morning stiffness. This was also associated with improvement in the disease activity and the quality of life regarding DAS28 and HAQ-DI for both candesartan and atorvastatin groups as compared to baseline data and as compared to the control group throughout the three months follows up period.

As compared to baseline, group 3 showed significant elevation in liver enzymes which did not exceed the upper limit (ALT level: from 22.40±7.48 to 30.60±7.84 IU/l and AST level: from 23.13±8.45 to 29.40±7.16 IU/l). On the other hand, both group 2 and control group showed non-significant change in liver enzymes as compared to their baseline values. There was no significant change in kidney function (BUN and S.Cr) for all studied groups as compared to their baseline data.

Discussion

In this study, candesartan and atorvastatin were used as anti-inflammatory adjuvant therapy for RA because of their suggested suppressive effects on inflammatory cytokines. The release of inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β and TNF-α is attributable to the pathogenesis and activity of RA disease including joint pain, deformity, stiffness, general fatigue and disease progression14.

Our results are matched with the result reported by Benicky et al15 who stated that, ARBs (candesartan) produced a significant reduction of circulating IL-1β and TNF-α levels in animal models with brain inflammation.

Furthermore, Silveira and Refaat1617 reported that ARBS (losartan) and methotrexate combined therapy showed better results than methotrexate alone in reducing IL-1β and TNF-α levels in experimental models of arthritis.

The current results corroborated with those of Lapteva et al18 who reported that angiotensin II was involved in upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β. So, ARBS provoke downregulation of these cytokines in RA patients. ARBs cause AT1R blockade and stimulation of the angiotensin II type 2 receptors that has an opposite effect to that of AT1R with subsequent anti-inflammatory activity and improvement of local and systemic manifestations of RA disease19.

Tikiz et al20 reported a significant reduction in IL-1β and TNF-α serum levels in RA patients treated by 20 mg simvastatin in combination with conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for two months. In another study serum levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were reported to be decreased in arthritic rats treated with atorvastatin (10 mg/kg)21.

Similar to our results, Zhang et al22 reported that IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly decreased in rat models of Alzheimer's disease treated with atorvastatin. The authors suggested the anti-inflammatory effect of atorvastatin through its inhibitory effects on inflammatory cytokines. Li et al23 in their meta-analysis predicted the ant-inflammatory effect of atorvastatin in RA patients.

Our study showed improvement in clinical status in RA patients treated by candesartan (8 mg daily) regarding the number of tender and swollen joints, PGA and morning stiffness. This improvement could be explained on the basis that the anti-inflammatory activity of ARBs was accompanied by functional improvement. This result was in agreement with Silveira et al16 who reported the anti-inflammatory activity of ARBs through downregulation of inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α with subsequent improvement in local joint inflammation and decrement of the disease activity in experimental models of arthritis.

The effect of atorvastatin was investigated in RA patients and a significant decrease in CRP levels and significant improvement in clinical status as evaluated by DAS28 were demonstrated2425. Our results supported these findings. Our findings were in agreement with previous studies that showed significant improvement in DAS28, HAQ-DI, morning stiffness, CRP and ESR levels in RA patients treated by statins in addition to conventional DMARDs2627.

Atorvastatin showed a significant decrease in serum MDA level. In contrast, candesartan showed no significant change in MDA serum level. This result could be explained on the basis that atorvastatin might have anti-oxidant effect and counteracted the oxidative stress in RA patients. Former studies showed the antioxidant activity of atorvastatin in RA patients2829. In contrast to our result, Silveira et al16 reported that ARBs (losartan) decreased the levels of superoxide radical and the expression of NADPH oxidases, an oxidizing stress marker in antigen-induced arthritic mice. Our results were in agreement with Perry et al30 who reported that treatment of RA patients with ARBs (losartan) resulted in a significant decrease in acute phase reactants including CRP and ESR levels.

A direct functional relationship has been reported between the acute phase reactant CRP and angiotensin II6. The authors reported that high level of angiotensin II was associated with high CRP level and subsequently ARBs resulted in decline of CRP level.

This current study reported a significant decrement in RF levels in RA patients treated by atorvastatin (20 mg daily), suggesting the immunomodulatory effect of atorvastatin, which seems in agreement with a study by Tascilar et al31 who confirmed the immunomodulatory effects of atorvastatin in RA patients. This study was limited by the relatively small sample size and the short follow up period.

In conclusion, both candesartan and atorvastatin showed anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that improved the clinical status and disease activity in RA patients through their suppressive effect on inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and TNF-α. Atorvastatin was superior to candesartan through its antioxidant effect. Atorvastatin and candesartan could represent a useful adjuvant therapy with other conventional therapeutic methods used for the management of RA patients. Large scale and longitudinal studies need to be done on RA patients with the implication of different doses of candesartan and atorvastatin to confirm its anti-inflammatory activity and others beneficial actions in patients with RA.

Acknowledgment:

Authors acknowledge all participants for their understanding and help during this work, and thank the physicians at Rheumatology clinics, Menofia University hospitals for their help and recommendations.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Autoimmune arthritides, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or peripheral spondyloarthritis following lyme disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:194-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence that cytokines play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3537-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin II activates the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-κB in human monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:826-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin II as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:569-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin II type 1 receptor as a novel therapeutic target in rheumatoid arthritis: In vivo analyses in rodent models of arthritis and ex vivo analyses in human inflammatory synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:441-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pleiotropic effects of statins: New therapeutic targets in drug design. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2016;389:695-712.

- [Google Scholar]

- Technological advances and proteomic applications in drug discovery and target deconvolution: Identification of the pleiotropic effects of statins. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22:848-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statins selectively inhibit leukocyte function antigen-1 by binding to a novel regulatory integrin site. Nat Med. 2001;7:687-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statins as antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory agents: A future in rheumatologic therapy? Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:393-407.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Normative values for the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index: Benchmarking disability in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:953-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the validity of the 28-joint disease activity score using erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR) as a disease activity index of rheumatoid arthritis in the efficacy evaluation of 24-week treatment with tocilizumab: subanalysis of the SATORI study. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:539-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;455:161-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin II AT 1 receptor blockade ameliorates brain inflammation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:857.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory actions of the angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist losartan in experimental models of arthritis. Peptides. 2013;46:53-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the effect of losartan and methotrexate combined therapy in adjuvant-induced arthritis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;698:421-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Activation and suppression of renin-angiotensin system in human dendritic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:194-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin II in inflammation, immunity and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179:137-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and statin treatment on inflammatory markers and endothelial functions in patients with longterm rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2095-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of atorvastatin in a rat model of adjuvant-induced arthritis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;516:282-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atorvastatin attenuates the production of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the hippocampus of an amyloid β1-42-induced rat model of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:103.

- [Google Scholar]

- The anti-inflammatory effects of statins on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systemic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:215-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trial of Atorvastatin in Rheumatoid Arthritis (TARA): Double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2015-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Therapy with statins in patients with refractory rheumatic diseases: A preliminary study. Lupus. 2003;12:607-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of statin therapy on C-reactive protein levels: The pravastatin inflammation/CRP evaluation (PRINCE): A randomized trial and cohort study. JAMA. 2001;286:64-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of simvastatin in the therapeutic approach of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmune Dis. 2013;2013:326258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atorvastatin and gemfibrozil metabolites, but not the parent drugs, are potent antioxidants against lipoprotein oxidation. Atherosclerosis. 1998;138:271-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of pravastatin and atorvastatin on coenzyme Q10. Am Heart J. 2001;142:E2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin receptor blockers reduce erythrocyte sedimentation rate levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1646-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Statins and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: A nested case-control study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2603-11.

- [Google Scholar]