Translate this page into:

Parasitic infections in HIV infected individuals: Diagnostic & therapeutic challenges

Reprint requests: Dr Veeranoot Nissapatorn, Associate Professor, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia e-mail: veeranoot@um.edu.my; nissapat@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

After 30 years of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, parasites have been one of the most common opportunistic infections (OIs) and one of the most frequent causes of morbidity and mortality associated with HIV-infected patients. Due to severe immunosuppression, enteric parasitic pathogens in general are emerging and are OIs capable of causing diarrhoeal disease associated with HIV. Of these, Cryptosporidium parvum and Isospora belli are the two most common intestinal protozoan parasites and pose a public health problem in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. These are the only two enteric protozoan parasites that remain in the case definition of AIDS till today. Leismaniasis, strongyloidiasis and toxoplasmosis are the three main opportunistic causes of systemic involvements reported in HIV-infected patients. Of these, toxoplasmosis is the most important parasitic infection associated with the central nervous system. Due to its complexity in nature, toxoplasmosis is the only parasitic disease capable of not only causing focal but also disseminated forms and it has been included in AIDS-defining illnesses (ADI) ever since. With the introduction of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART), cryptosporidiosis, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, strongyloidiasis, and toxoplasmosis are among parasitic diseases reported in association with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). This review addresses various aspects of parasitic infections in term of clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic challenges associated with HIV-infection.

Keywords

AIDS

anti-parasitic treatment

diagnosis

HAART

HIV-infected individuals

IRIS

parasitic opportunistic infections

Introduction

In 1981, the first patient diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the USA was reported. The growing number of people living with HIV has constantly been detected the world over and in particular from the three main continents, Asia, South America and sub-Saharan Africa. In a global report on AIDS epidemic, it is estimated that there are 33.3 million (31.4-35.3 million) adults and children living with HIV around the world. The data from epidemiological surveillances have further shown that there are an estimated 2.6 million (2.3-2.8 million) people newly infected with HIV. About 370,000 (230,000-510,000) children are newly infected with HIV. It is also believed that there are 1.8 million (1.6-2.1 million) annually AIDS-related deaths worldwide1. Opportunistic infections (OIs) are one of the existing identified causes that aggravate the condition of HIV-infected patients. Of these, parasites play an important role as OIs and are one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in HIV/AIDS patients. The spectrum of parasitic opportunistic infections (POIs) affecting HIV-infected individuals is divided into protozoa and helminthes (nematodes, cestodes, and trematodes). These POIs are not only associated with symptomatic HIV-infected patients but also are more evident with decreasing immune state (CD4+ cell count < 200 cells/μl), which constitutes an ADI. Among POIs, cryptosporiosis, isosporidiosis and microsporidiosis are the main enteric/intestinal parasitic infections, while leishmaniasis and toxoplasmosis are the main systemic POIs reported in HIV-infected patients. Of these, cryptosporiosis, isosporidiosis, and most importantly toxoplasmosis with brain involvement are the three key parasitic diseases which have been included in the Centers for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) case definitions for AIDS2. This review therefore aims to highlight the important issues pertaining to these POIs in term of clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in HIV-infected patients. It also provides a better understanding of clinical scenario and future management of these POIs at the time of widely access to the HAART, particularly in resource limited settings.

Intestinal or enteric parasites in HIV/AIDS patients

Diarrhoea in patients with AIDS is significantly caused by intestinal parasites23. The main aetiologic agents are intracellular protozoa, Isospora belli, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Cyclospora spp4. However, infection with other extracellular parasites is also related to diarrhoeal disease in AIDS patients. Among these parasites, Entamoeba histolytica, Giardia intestinalis and Strongyloides stercoralis are the most important5.

Several studies have been carried out to determine the presence of intestinal parasites in HIV patients. A higher prevalence of intracellular parasites, particularly Cryptosporidium spp. and S. stercoralis was found in HIV positive cases, than extracellular parasites6. Since cellular immunity is the major defense mechanism against intestinal parasitic infections7, the association between intestinal parasites and individuals with reduced immunity due to CD4+ T-lymphocyte reduction in HIV/AIDS is well predictable, particularly from cases presented with diarrhoea8.

Intestinal protozoan parasites

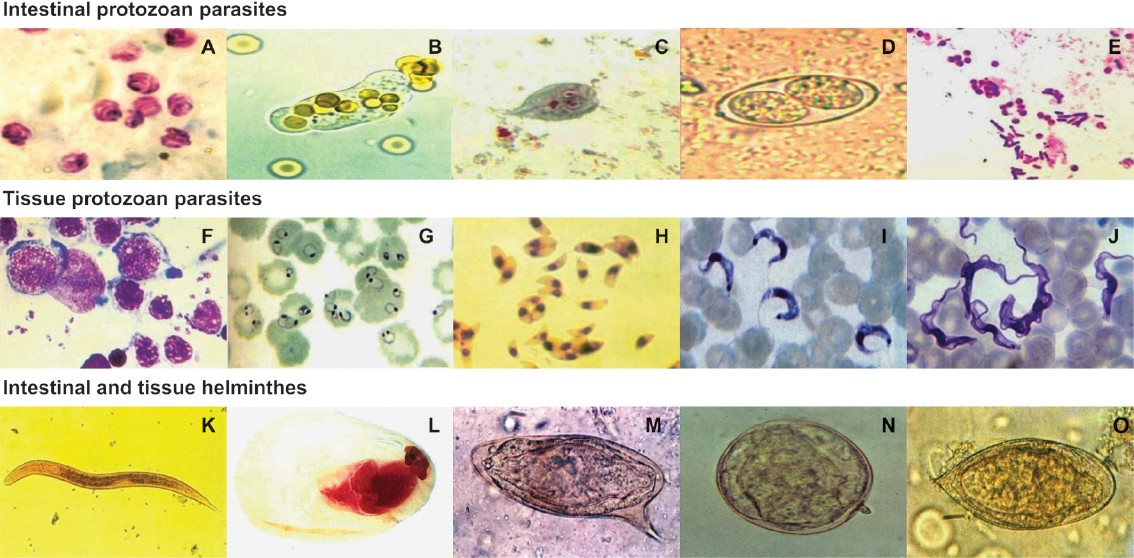

C. parvum , E. histolytica, G. intestinalis, I. belli and Microsporidium spp. (Fig. 1) are among intestinal protozoan infections which have commonly been reported in HIV-infected patients. Ascaris lumbricoides, hookworms, Trichuris trichiura and S. stercoralis are intestinal helminthic infections, which have also been reported in these patients9. These enteric parasitic infections usually produce diarrhoeal disease by infecting the small or large intestine, or both. They are also often found in children and adults in tropical climates. Amoebiasis caused by infection with E. histolytica leads to bloody diarrhoea and hepatic disease. The other protozoa produce persistent diarrhoea with or without malnutrition. Severe enteritis and chronic diarrhoea in HIV infected patients are often documented as a consequence of multiple opportunistic intestinal protozoa infections and can result in significant morbidity and mortality10.

- Microscopic images from clinical samples. (A) Oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvumfrom a stool sample (Modified acid-fast stain). (B) Trophozoite of Entamoeba histolyticafrom a fresh stool sample. (C) Trophozoite of Giardia intestinalisfrom a stool sample (Trichrome stain). (D) Oocyst of Isospora belli from a stool sample. (E) Spores of Microsporidiam spp. from a stool sample (Gram-chromotrope stain). (F) Oval-shaped Leishmania donovani amastigotes from a bone marrow aspirate (Giemsa stain). (G) Ring form of Plasmodium falciparum from a blood smear (Giemsa stain). (H) Trophozoites of Toxoplasma gondii from intra-peritoneal fluid (Giemsa stain). (I) Monomorphic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi in a blood smear (Giensa stain). (J) Polymorphic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense in a blood smear (Giemsa stain). (K) Rhabditiform larva of Strongyloides stercoralis from a stool sample. (L) Cysticercus cellulosae (Carmine and fastgreen stain). (M) Egg of Schistosoma mansonifrom a stool sample. (N) Egg of Schistosoma japonicum from a stool sample. (O) Egg of Schistosoma haematobium from a stool sample. Magnifications: (A-J)=1000 ×, (K, L)=100 ×, (M-O)=400 ×.

Cryptosporidium spp., Isospora belli and Microsporidium spp.

Cryptosporidiosis and isosporiasis have been categorized by CDC as ADI2. These are the two most common intestinal protozoan parasites causing diarrhoea and pose a public health problem in AIDS patients. Recent reports from France indicated the increase of isosporiasis from 0.4 per 1000 patients in the pre-HAART era (1995-1996) to 4.4 per 1000 patients in the HAART era (2001-2003)11. The prevalence of cryptosporidiosis varied according to geographical locations. In Southeast Asia, the infective rate of C. parvum is up to 40 per cent12. In clinical cryptosporidiosis, chronic diarrhoea with watery stools, weight loss and dehydration are the prominent features in symptomatic patients13. Cryptosporidiosis occurs in AIDS patients when the CD4+ cell count is < 200 cells/μl14. Microsporidium is an obligate intracellular microorganism that was recently reclassified from protozoa to fungi. It has emerged as the causes of OIs associated with diarrhoea and wasting in AIDS patients especially in developing countries where combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) is not always accessible15. Interestingly, most studies found that Cryptosporidium spp. was the most common intestinal parasitic co-infection with Microsporidium spp1416. Clinical symptoms and disease associated with microsporidiosis vary with the status of the host's immune system. Persistent diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weight loss are common clinical symptoms15. Higher prevalent rates of these intestinal parasitic infections are found related to CD4+ cell count of <100 cells/μl17. With greater awareness and implementation of better diagnostic methods, it was demonstrated that microsporidia contribute to a wide range of clinical syndromes in HIV-infected individuals18. Therefore, primary effectiveness of prevention and control strategies against these parasitic infections should be implemented in HIV/AIDS patients particularly in resource limited settings.

Entamoeba histolytica

E. histolytica is one of the most important parasitic diseases in developing and developed countries. It infects approximately 50 million people worldwide. Although, most subjects infected with E. histolytica are asymptomatic, it accounts for more than 100,000 deaths annually19. E. histolytica is unique among amoeba in its ability to disrupt the intestinal mucosa causing colitis and the capability for further haematogenous spread, producing potentially fatal abscesses in the absence of appropriate therapy20.

E. histolytica infection is common in homosexual men, particularly those sexually active HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) are at greater risk of developing amoebic disease than HIV-uninfected MSM and the general population21. Transmission in these men occur by oral-genital or oral-rectal sexual practices21.

A high prevalence of E. histolytica infection in HIV/AIDS patients in various countries has been reported22. E. histolytica seropositivity in HIV-infected individuals was found to be higher in patients with a CD4+ cell count of <200 cells/μl22. It is unclear whether HIV infection is a risk factor for E. histolytica infections but it has been suggested that these are more susceptible to an invasive form of the disease than are normal population23. The common clinical symptoms and signs of amoebic liver abscess (abdominal pain, fever and chills, and abdominal tenderness) show a more insidious onset of illness in term of longer duration of hospital stay in HIV patients than in normal population24 but in most cases there are no significantly differences between the two groups25.

Giardia intestinalis

G. intestinalis is one of the most common pathogenic intestinal protozoan parasites of humans causing acute and chronic diarrhoea throughout the world. It is becoming increasingly important among HIV/AIDS patients. Although giardiasis was not considered a major cause of enteritis in AIDS patients, there are reports that some cases of acute and chronic diarrhoea may be associated with G. intestinalis infection426.

In HIV patient as well as in healthy individuals, infection with G. intestinalis is frequently asymptomatic but can also cause abdominal cramps, diarhoea with flatulence and weight loss27. These symptoms generally begin 1-2 wk after infection, and may last 2-6 wk. Studies from Brazil26 indicate a high prevalence of G. intestinalis infection among HIV/AIDS patients, whereas studies form Ethiopia found no significant increase in infection rates of G. intestinalis28. However, HIV patients did have an increased probability of more severe symptoms when infected with this organism, especially in the most advanced stage of disease29.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of amoebiasis and giardiasis is usually made by examination of stool under microscope for evidence of trophozoites or cysts. For cryptosporidiosis, faecal sample may need acid fast staining and view under microscope for oocyst.

Stool examination - The introduction of stool examination for specific antigen tests has improved diagnostic capabilities. Immunochromatography card for the rapid detection of protozoal proteins from a small sample of stool are available from several different commercial sources and are more sensitive and more specific (>90%) than the traditional microscopec examinations. These kits are available from Meridian (ImmunoCard STAT!® Cryptosporidium/Giardia), Alexon-Trend (Xpect® Giardia), Tech-lab (PT5012-Giardia II). The benefits of antigen detection methods are that there are no requirement for expert microscopists and require less time than conventional microscopic method.

Serological diagnosis - Although the available commercial kits were claimed to be the best single test for diagnosing intestinal protozoa, microscopic examination of stool could identify other parasites, in addition to each specific detection kit, that can cause diarrhoea. Therefore, microscopic examination of stool has value beyond diagnosing a single disease.

Treatment: Treatment for amoebiasis and giardiasis involves nitroimidazoles such as metronidazole (Flagyl), which has been used successfully for more than four decades. Undesirable side effects including anorexia, nausea, vomiting, malaise, metallic taste, potential teratogenicity and failures in treatment in normal and HIV patients have been reported30.

In the USA, the only drug approved by FDA for treating giardiasis is furazolidone (Furoxone) for 7-10 days. Nitazoxanide (Alinia) could become the preferred drug as it comes in a liquid form which may be easier for children to swallow. Tinidazole (Tindamax) and ornidazole are alternatives to metronidazole. Although these have many of the same side effects as metronidazole, but can be given in a single dose. Diloxanide furoate (Furamide) was also recommended in case of failure treatment with metronidazole31.

Certain drugs such as co-trimoxazole or nitazoxanide seem to have partial treatment for cryptosporidiosis. There is also no effective drug to treat patients infected with Microsporidium spp. To date, no specific drug has been shown to be effective against these infections. One recent study found no oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp. were detected in stools of patients receive HAART32.

Diseases due to tissue parasites in HIV/AIDS patients

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania spp., an haemoflagellate, intracellular and zoonotic protozoan parasite. It is one of the most common neglected tropical diseases. Global epidemiological surveillance shows that infection with Leishmania spp. was found in more than 12 million people worldwide and 2 million new cases are reported annually33. Of these, 350 million people are considered as “high risk” and the incidence of leishmaniasis is increasing33. Overall, the disease has been reported from 88 developing countries, particularly found among people living in poor conditions. There are two basic forms of clinical manifestations, namely, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), a disfiguring and stigmatizing disease, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) or kala azar, a life-threatening but treatable condition if diagnosed early. VL is prevalent in approximately 70 countries and South Asia (estimated 300,000 cases in 2006); India is among the largest foci of the disease followed by East Africa (30,000 cases per year) and Brazil (4,000 cases reported in 2006)34. There is an increase on the occurrence of new foci and the incidence of VL in east Africa. CL, cutaneous form of leishmaniasis, is geographical distributed among 82 countries whereby the predominant foci are countries in middle-east Asia, east Africa, South America and southern Europe36. CL has several (localized, diffuse and mucocutaneous) clinical features which depend on the Leishmania species involved (Fig. 2). Mucocutaneous is the most severe form that causes disfiguring lesions and mutilation of the face.

- Clinical features of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Chronic ulcerative lesions of the lower limb as a result of infection with Leishmania tropica.

The impact of HIV/AIDS pandemic is not only changing the natural history of leishmaniasis34 but also increasing the risk (100 to 1,000 times) of developing VL in endemic areas, reducing the therapeutic response, and increasing the possibility of relapse cases37. Leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients is mainly VL, however, some cases of CL have also been reported in HIV-infected patients from endemic countries such as in Africa38 and South America39. Since the introduction of HAART, the numbers of Leishmania-HIV co-infected cases from countries where they are endemic in Europe are rapidly declining.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients may not be straightforward due to clinical variations from non-specific to atypical features found in majority of cases. Further, the presence of clinical signs such as hepatomegaly is typically less frequent in patients with this co-infection and about half of these patients present with clinical pictures that mimic with other common OIs making clinical diagnosis difficult. In suspected cases of leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients, combined diagnostic investigations (if applicable) are recommended to confirm the diagnosis.

Parasitological diagnosis - Microscopic examination and culture are conventional methods that have historically been used to detect the present of Leishmania spp. from different biological specimens and considered as the gold standard. These methods may also help in the detection of treatment failures in cases of leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients35.

Serological diagnosis - Antibodies detection using several serological tests are available, including immunofluorescent antibody test (IFAT), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using crude antigen or rK39 antigen, immunoblotting, direct agglutination test (DAT), and the Rk39 dipstick test35. The Rk39 dipstick test is a simple, rapid, inexpensive and non-invasive method with a sensitivity of >90 per cent for the detection of VL in India40. However, sensitivities as low as 20 per cent have been reported for VL-HIV co-infected patients in Europe35. In cases of severe immunodeficiency, these serological tests can be of limited use because antibodies to Leishmania spp. may be absent despite an acute leishmaniasis2941. Furthermore, antibodies to Leishmania spp. can cross-react with other parasitic infections such as those of Trypanosoma spp. which make the use of some serological tests problematic35. Since the results of seropositivity vary according to serological tests performed, at least two different serological tests are recommended for each patient to enhance the sensitivity of antibody production42.

Molecular diagnosis - PCR is a useful technique for the detection and identification of different Leishmania species directly from clinical samples43. PCR assays applied to bone marrow and peripheral blood specimens is a useful tool for the diagnosis of VL-HIV co-infected patients35. By using non-invasive biological specimens, PCR assays also seem to be feasible for long-term monitoring the efficacy of treatment and the prediction of relapse cases44.

Treatment: Antileishmanial therapy consists of the antimonial compounds (sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate), miltefosine, and amphotericin B is used for the treatment of leishmaniasis in HIV-infected patients. Patients with Leishmania-HIV co-infection generally have low cure rates, high drug toxicity and high mortality rates. Moreover, low CD4+ cells count and recurrent relapses may contribute to temporary recovery and resistance to the previous drug regimens used35.

The antimonial compounds have been used for past decades as the first line drug for treatment because of their low cost and availability in most countries. However, the compounds are well known for their toxicities such as severe vomiting and emerging drug resistant45. The compounds have high toxicity, high mortality rate and potentially stimulated HIV-1 replication in in vitro, therefore, it is not recommended for the first-line treatment of Leishmania-HIV co-infected patients35.

Lipid formulations of amphotericin B (Liposomal amphotericin B; L-AmB) is the drug of choice for treating VL46. Due to its cost, this therapeutic agent is more commonly used in developed than in resource-poor countries41. A European study demonstrated that L-AmB with a total dose of up to 30-40 mg/kg was well tolerated in small numbers of Leishmania/HIV-coinfected patients but this therapy did not prevent relapse cases47. Data on AmB lipid complex or L-AmB used for secondary prophylaxis in co-infected patients is scanty; therefore, more study are needed to prevent the high possibility of recurrent leishmaniasis in these patients.

Malaria

Of the four Plasmodium species: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. ovale, P. vivax is the most common cause of malaria particularly found in endemic areas and P. falciparum is the main cause of severe malaria that leads to high morbidity and mortality. The major foci of malaria are found in many regions such as South America, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa48. Approximately 300 to 500 million children are infected with malaria each year leading to more than 1 million deaths annually in sub- Saharan Africa49. About 25 million pregnant women are at risk of infection of P. falciparum in this region48. A higher parasites load was detected in HIV-infected multigravidae and also the increasing rates of fever due to malaria with the progressive immunosuppression in HIV-infected partients49.

Diagnosis: Parasitological diagnosis - The diagnosis of clinical malaria is based on a high index of suspicion in both the patient's history of exposure and clinical presentation. The definite diagnosis requires the direct identification of malarial parasite species in the peripheral blood specimens (parasitaemia) from thick and thin blood smears using Giemsa staining technique.

Serological diagnosis - There are a few commercial diagnostic kits available in the detection of anti-malarial antibodies namely ParaSight-F is the simple and accurte diagnostic kits for P. falciparum infection50.

Neuroimaging diagnosis - In cerebral malaria, brain computed tomography (CAT scan) shows cerebral oedema by effacement of the cortical sulci and small or slit-like ventricles, and if it occurs with hypoattenuation of the basal ganglia or cerebellum, a sign of poor prognosis51. Brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) demonstrates diffuse swelling with or without oedema, as well as multifocal cortical and subcortical lesions52. In fatal cases of cerebral malaria, brain CAT scan and MRI reveal a common finding of transtentorial herniation53.

Treatment: The interaction between HIV infection and malaria has been well described over the past few years. As a standard guideline, co-trimoxazole is daily recommended in HIV-infected patients, including pregnant women54. Apart from antimalarial treatment, implementation of insecticide-treated nets, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, and ART play an important role in reducing the morbidity and mortality of clinical malaria in HIV-infected patients. There are many more treatment challenges that need to be answered regarding clinical malaria in HIV-infected patients: the role of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients undergoing ART, the efficacy of antiretroviral drugs against malaria, the synergistic action between antimalarial and antiretroviral treatments, and the effect of antifolate resistance under co-trimoxazole prophylaxis54.

Neurocysticercosis

Neurocysticercosis (NCC), caused by a larval tapeworm Taenia solium, is the most common helminthic infection of the central nervous system and the most common cause of patients with acquired seizure. Cysticercosis is highly endemic in most developing countries such as Asia, Latin America, parts of Oceania, and sub-Saharan Africa where pigs are raised55. Faeco-oral contamination is the main route of transmission through accidentally ingestion of T. solium egg found among infected humans. Clinical presentations of patients with NCC depend on the number, size, location of CNS lesions, and the host immune response56. Of these, seizures are the most common clinical presentation of NCC, but other syndromic features, such as headache, hemiparesis and ataxia may also be seen in these patients.

Diagnosis: Though, NCC is not that common compared to other OIs in HIV-infected patients, misdiagnosis can easily lead to fatal outcome in immunocompromised hosts. The definitive diagnosis of NCC is recommended based on combined histology, radio-imaging, serology, and clinical symptoms. The diagnosis of NCC is made on histopathologic evidence of NCC, CAT scan or MRI showing a scolex within a cystic lesion, or neuroimaging showing a lesion compatible with NCC or a clinical response to initial therapy of NCC, combined with serological evidence of infection with T. solium using CSF ELISA57.

Treatment: Albendazole and praziquantel are the mainstay drugs for treatment of NCC, especially for meningeal infection and steroids should be administered to reduce oedema as a result of medical treatment58.

Schistosomiasis (Bilharziasis)

Schistosomiasis, a neglected tropical disease or a man-made disease, is caused by five species of blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma: S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. haematobium, S. intercalatum, and S. mekongi. This parasitic disease infects 200 million people worldwide and about 600 million people are at high risk to the infection in 72 endemic countries59. The infection with Schistosoma spp. is mostly transmitted through water contact and requires an intermediate mollusk host to complete its life-cycle. Factors contribute to the occurrence of this systemic helminthic infections in new geographical foci are international travel, refugee and population migration, and the new development of water resources60.

In HIV-infected patients, a couple of studies showed that up to 17 per cent of HIV-infected patients from sub-Saharan Africa had seropositive for schistosomiasis61. There are three main clinical diagnoses of schisto-somiasis (gastrointestinal, disseminated and CNS) reported in HIV-infected patients. Gastrointestinal schistosomiasis is the most common form and patients typically present with weight loss, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and odynophagia62. Only a few cases of disseminated and neurkoschistosomiasis (NSS) have been reported in HIV-infected patients63.

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of NSS is difficult because clinical CNS symptoms are non-specific and laboratory findings such as eosinophilia and the presence of Schistosoma eggs in clinical samples may not be present64. NSS should be included in the differential diagnosis in any patient who is from endemic area of schistosomiasis and who displays an acute encephalopathy of unknown origin.

Parasitological diagnosis - The definite diagnosis is based on the direct identification of the eggs in tissue biopsy specimens of patients with NSS compared to the supportive evidence on direct detection of Schistosoma eggs in stool (S. mansoni) or urine (S. haematobium) samples for patients with schistosomiasis65.

Serological diagnosis - In general, there are promising serological methods used for antibodies detection such as IgG, IgM or IgE by different diagnostic kits of ELISA, IHA or immunofluorescence66. These methods are sensitive and useful in the diagnosis of schistosomiasis of both affected people living in endemic areas and among travellers. However, there are some limitations to these commercial kits that need to be rectified in order to avoid misdiagnosis: the antibodies persist even after parasitological cure65, or the possibility of cross-reactivity with other helminthic infections. Another promising method of the detection of circulating adult worm antigen and soluble egg antigen is in using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies from various clinical samples67.

Neuroimaging diagnosis - CAT scan and MRI are useful tools in the investigation of NSS. CAT scan finding typically shows single or multiple hyperdense lesions surrounded by oedema with variable contrast enhancement68, while, MRI of the brain demonstrates a characteristic “arborized” appearance with linear enhancement surrounded by punctate enhancing nodules69.

Treatment: The drug praziquantel, steroids and surgery are currently available as the mainstay for treatment of NSS. A 5-days course of praziquantel of 50 mg/kg/day divided in two daily doses is recommended for treatment of NSS70. Artemether, an antimalarial drug and a synergistic drug with praziquantel is effective against the immature migrating larvae (schistosomula)71. In non-compliance to praziquantel, oxamniquine of 30 mg/kg daily for 2 days can be alternatively used for treatment, particularly for the infection with S. mansoni70. In HIV-infected patients, the treatment is effective for schistosomiasis but it shows a high reinfection rate and correlates with a low CD4+ cell count72.

Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis, a human intestinal helminthic infection. This parasitic disease has been found geographically distributed in both tropical and subtropical foci. In HIV-infected patients, hyperinfection syndrome (HS) and disseminated infection (DI) are uncommon but usually occurs in HIV-infected patients with CD4+ counts of <200 cells/μl. So far, very few cases of systemic/disseminated strongyloidiasis have been reported in HIV-infected patients73. The low incidence was due to indirect development of S. stercoralis infective larvae in the gut of HIV-infected patients do not favor disseminated strongyloidiasis74. Only a (<30 cases) of strongyloidiasis HS in HIV-infected patients have been reported75.

Diagnosis: Parasitological diagnosis - Definitive diagnosis is confirmed by direct identification of Strongyloides spp. rhabditiform larvae in different clinical specimens: stool, sputum, serum/blood smears, bronchial aspirates, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), peritoneal fluid or ascitic fluid76. Stool examination is a simple and cheap method but the screening for Strongyloides infection cannot rely solely on this method particularly in cases of HS where there is low number of larvae in the stool. The Harada-Mori filter paper appears to be a less successful culture method for Strongyloides than blood agar plate culture77.

Serological diagnosis - ELISA should be performed if strongyloidiasis is suspected but not detected by parasitological diagnosis77. Serology may give false negative results in patients with disseminated disease, may cross-react with other helminthic infections, or cannot differentiate between recent and remote infections.

Skin testing - The sensitivity of skin test decreases in the immunocompromised and most likely found in HIV-infected patients due to the similar effect and this method is not easily accessible75.

Treatment: Ivermectin 200 μg/kg/day is the treatment of choice for strongyloidiasis, in cases of HS, and DI, should be continued at least for 7-10 days or until the clinical symptoms are resolved57. Secondary prophylaxis is recommended in immunocompromised individuals e.g., a 2-day course of ivermectin every 2 wk may prevent HS or DI75.

Toxoplasmosis

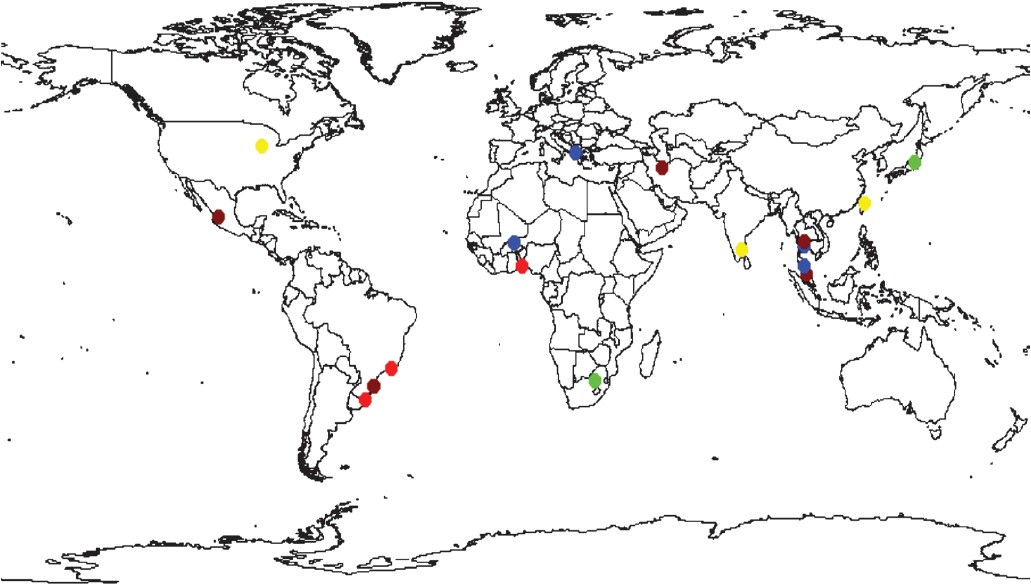

The coccidian Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous, intracellular, protozoan parasite that causes toxoplasmosis. T. gondii infection can enhance the immunodeficiency found after HIV-1 infections. Up till the present day, toxoplasmosis is medically the most important POIs of both epidemiological and clinical aspects in association with HIV-infected patients, which has been reported worldwide. The high prevalent rates of latent Toxoplasma infection (41.9-72%) in patients infected with HIV were reported in South America and in approximately half of the studies (≥40%) from the Asian continent. In North America, however, the rate of Toxoplasma infection was low (Fig. 3). Latent stage of toxoplasmosis is still prevalent as an infection that coexists with HIV pandemic. In concurrence with HIV infection, more than 95 per cent of cerebral toxoplasmosis (CT) occurs primarily due to reactivation of latent Toxoplasma infection and CT is one of the most frequent OIs, particularly in patients with full-blown AIDS. CT is the most common clinical presentation of toxoplasmosis and is one of the most frequent causes of focal intracerebral lesions that complicates AIDS78. When HIV-infected patients develop CT this poses many diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for clinicians79.

- Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients. Light red equals prevalence above 60%, brown equals 40-60%, blue 20-40%, yellow 10-20% and green equals prevalence <10%. White equals absence of data.

In general, CT can be prevented by primary behavioural practices in avoiding acquisition of Toxoplasma infection such as consumption of well cooked meat, avoiding close contact with stray cats, contaminated soil and/or water, and receiving unscreened blood transfusions. Compliance to both therapeutic regimens for treatment and prophylaxis of toxoplasmosis is an imperative to prevent relapse of CT in areas where HAART is not fully accessible for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Diagnosis: Among patients with AIDS, cerebral involvement is more common and more serious than extracerebral toxoplasmosis. The definitive diagnosis is crucial for CT patients by directly demonstrating the presence of the tachyzoite form of T. gondii in the cerebral tissues. The presumptive diagnosis for CT, including the clinical presentations, radio-imaging findings, molecular and sero-diagnosis for Toxoplasma infection, and good response to anti-Toxoplasma therapy are widely accepted in clinical practice. The favourable outcome of CT is the improvement of clinical and radiological features after 2 to 3 wk of initiated empirical therapy.

Serological diagnosis - CT poses a diagnostic problem that relies on classical serological methods to detect anti-Toxoplasma immunoglobulins because blood samples from patients with immunodeficiency can fail to produce sufficient titres of specific antibodies. Seroevidence of Toxoplasma infection, independent of antibody levels, is generally seen in all patients before developing CT80. Most cases have high titres of anti-Toxoplasma IgG antibodies with high IgG avidity that provides serological evidence of infection81 and this is the result of a secondary reactivation of latent or chronic Toxoplasma infection81. Therefore, it is important to determine the Toxoplasma serostatus in all HIV-infected patients to define the population at risk for CT.

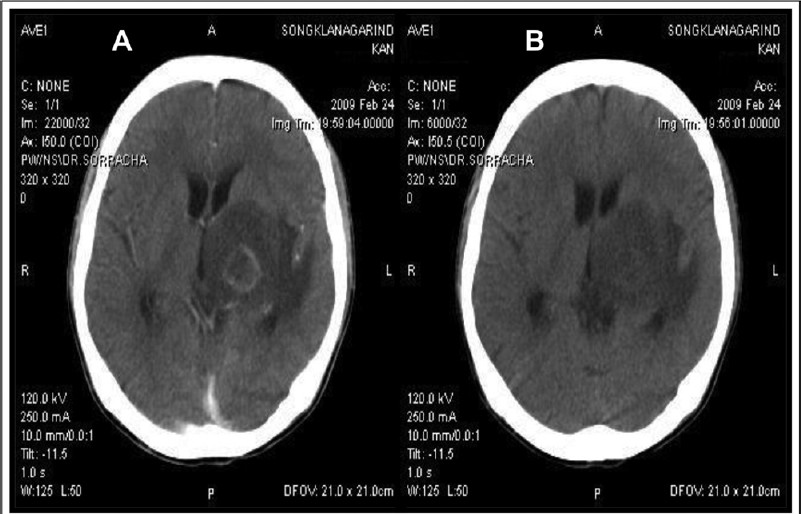

Radiological diagnosis: Radio-imaging findings, either by CAT scan or MRI, are useful tools for the presumptive/empirical diagnosis of CT. CT usually causes unifocal, and more frequently multifocal lesions, or less likely diffuse encephalitis. These findings are however, not pathognomonic of CT. Radiological diagnosis82 can be classified as typical findings of hypodense lesions with ring-enhancing and perilesional oedema, and are observed in ~80 per cent of CT cases (Fig. 4). A typical pattern of hypodense lesions found without contrast enhancing, CAT scan without focal lesions and MRI demonstrating focal lesions, and diffuse cerebral encephalitis without visible focal lesions, are shown in about 20 per cent of CT cases. An unusual but highly suggestive image of CT is the ‘eccentric target sign’, which is a small asymmetric nodule along the wall of the enhancing ring83. A CAT scan seems to be a sensitive diagnostic method for patients with focal neurological deficits; however it may underestimate the minimal inflammatory responses seen during early disease84. MRI is recommended to be performed in patients with; neurological symptoms and positive serology to anti-Toxoplasma antibodies whose CAT scans show no or only a single abnormality, or persistent or worsening focal neurological deficits of disease if results of the initial procedure were negative85.

- Neuroimaging findings of cerebral toxoplasmosis in an AIDS patients. (A) Contrast enhanced CAT brain showed a ringenhancing lesion and marked surrounding vasogenic brain oedema. (B) Contrast enhanced CAT brain showed a resolution of cerebral lesion after 4 wk of anti-Toxoplasma therapy.

Molecular diagnosis - The direct detection of T. gondii DNA in biological specimens by PCR has provided a major breakthrough for the diagnosis of toxoplasmosis86. PCR techniques are suitable for patients with AIDS because these methods do not depend on the host immune responses and allow for direct detection of T. gondii DNA from a variety of clinical samples.

Other diagnostic methods - Brain biopsy is generally reserved for those patients with a diagnostic dilemma or do not fulfill the criteria for presumptive treatment and for those patients who fail to improve clinically or radiologically over the succeeding 10-14 days after being empirically treated for toxoplasmosis initially. Stereotactic brain biopsy (SBB) is then required to institute specific and appropriate therapy8587. Surprisingly, SBB is not commonly used for the diagnosis of CT or CT-associated other opportunistic CNS diseases in Asian countries88 compared to other settings where CT cases have been reported in patients with AIDS. Brain biopsies do not influence survival of CT patients89. SBB is an efficient, safe and important diagnostic procedure. In selected patients even expensive investigations should be undertaken before considering specific therapy and cost-effective home-care90. This procedure should be performed early to achieve a prompt and accurate diagnosis and to guide the therapeutic scheme for AIDS patients with focal brain lesions91.

Treatment: Most patients with CT respond well to anti-Toxoplasma agents as demonstrated by findings from studies in various settings. However, about 10 per cent of CT cases died despite what was thought to be adequate treatment82. There are a few options other than anti-Toxoplasma regimens used as first-choice initial therapy; 6 wk with sulphadiazine (1.0-1.5 g per oral PO every 6 h) with pyrimethamine (100-200 mg [PO] loading dose, then 50 mg PO daily) and folinic acid (10-20 mg PO daily) that can reduce the haemato-toxicities related to pyrimethamine92.

Resistance to standard combination therapy (pyrimethamine and sulphadiazine) was reported in patients with CT93. Atovaquone has consistently been found to be a promising therapeutic for salvage therapy in CT patients who were intolerant to or who failed standard regimens94. However, the role of atovaquone in the treatment and prophylaxis of CT in AIDS patients is not well defined and more studies are required before a firm recommendation can be made95.

Trypanosomiasis: American trypanosomiasis

American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) is caused by T. cruzi, a hemoflagellate, intracellular and zoonotic protozoan parasite. It is a significant public health problem for not only people living in endemic areas (~15-16 million) in Latin American countries96 but also in non-endemic countries due mainly to immigration to European countries, Canada or the United States97. The clinical manifestation of Chagas’ disease is divided into three stages: the acute stage, often remains unnoticed or misdiagnosed due to its initial clinical pictures are non-specific to Chagas’ disease, intermediate stage, a period of asymptomatic carriage of parasites which remains life-long or chronic stage, multi-organs involvement after an incubation period of 10 to 30 years.

T. cruzi is one of the tropical pathogens that can coexist within HIV-infected individuals. T. cruzi/HIV co-infection in some areas of Mexico, Central and South American regions occur as a result of the geographical overlapping of these two pathogens, the occurrence of global migration and international travel98. This dual infection occurs because of the secondary reactivation of chronic (latent) T. cruzi infection triggered by immunosuppression in HIV-infected patients98. In regions where Chagas’ disease is endemic, the reactivation of this parasitic infection may be the first presentation of patients with HIV infection99100 and it can cause a high mortality rate among these coinfected patients101. HIV-related immunosuppression changes the clinical manifestations of Chagas’ disease including the central nervous system involvement102. Patients with reactivated CNS chagasic disease are more common in 75-80 per cent of patients with AIDS103. Since 2004, reactivated Chagas’ disease (meningoencephalitis and/or myocarditis) was included in the AIDS in Brazil.

Diagnosis: In HIV-infected patients, the reactivation of Chagas’ disease can be easily misdiagnosed as the clinical features and pathological appearance mimic with other brain diseases especially with CT. In such cases, Chagas’ disease should be included in the differential diagnosis in HIV-infected patients presenting with focal neurological deficits which requires further investigations98. Chagas’ disease poses a diagnostic dilemma in clinical practice and clinician require highly suspicion of patients with chagasic encephalitis who arrive from endemic areas, has a history of blood transfusion or intravenous drug use, and has no response to empirically anti-Toxoplasma therapy104.

Parasitological diagnosis - The definitive diagnosis is based on the direct detection of trypomastigote stage of T. cruzi in relevant clinical specimens using thick smears or Strout's concentration method, and CSF smears. In HIV-infected patients, the identification of trypomastigotes in CSF sample is the definitive diagnosis of chagasic encephalitis. Based on earlier studies, trypomastigotes are more frequently observed in the blood of HIV-infected patients with low level of CD4+ cell count105. In cases of focal brain lesions with an initial empiric anti-Toxoplasma therapy, a stereotactic biopsy should be performed to identify of T. cruzi amastigotes in all brain specimens, to confirm the presence of parasites by using the immunohistochemical method and to differentiate reactivated Chagas’ disease from CT106. Therefore, parasitological studies and histopathology are the confirmatory diagnostic tools for chagasic encephalitis in HIV-infected patients104.

Serological diagnosis - ELISA, indirect immunofluorescence, and indirect haemagglutination are the most common serological methods used to detect antibodies levels indicating the latent or recent infections with T. cruzi. The reactive results are usually obtained from at least two or three serological assays107 and the negative result does not exclude the diagnosis especially for disease reactivation108.

Neuroimaging diagnosis: Neuroimaging finding is the initial diagnosis especially for patients with chagasic encephalitis. The characteristic of space occupying lesions are found to be similar as to those of CT98107. Based on the lesion location, it can suggest the aetiological agent. CAT scan typically shows hypodense, single or multiple, irregular ring enhancing lesions predominantly located in the white matter of the brain lobes108. However, the neuroimaging finding might be normal in a few cases102. MRI demonstrates a heterogenous expansive lesion with mass effect, hypointense in T1 and hyperintense in T2 and FLAIR sequences, with irregular or ring enhancement106. Although Chagas’ disease and toxoplasmosis rarely co-exist in the same patient, PCR or microscopy is essential in differentiating these two pathogens and in preventing disease progression as well as fatal outcome of these patients109.

Molecular diagnosis - PCR is a useful tool for the detection of T. cruzi DNA from various biological specimens: peripheral blood for the early diagnosis of reactivated Chagas’ disease110 and for evaluation of the efficacy of anti-T. cruzi therapy111. The real-time PCR system is considered as an alternative to conventional PCR techniques as it is simpler, faster and more reliable. Moreover, the reduced risk of contamination and the possibility of quantification are added values to this method112.

Treatment: In HIV-infected patients, benznidazole 5 mg/kg daily divided in two doses for 60-90 days is recommended treatment for reactivated Chagas’ disease103113 and nifurtimox 8-10 mg/kg daily divided in three doses for 60-120 days is an alternative option even though clinical experience is generally not encouraging103. After resolution of the CNS Chagas’ disease, benznidazole 5 mg/kg given three times per week is recommended for a lifetime secondary prophylaxis57. The exacerbation of HIV viral load simultaneous with asymptomatic reactivation of chronic Chagas’ disease114. In HIV patients with seropositive for T. cruzi, it might be beneficial to administer a single course of treatment with benznidazole and nifurtimox. ART should be systematically initiated in Chagas/HIV-coinfected patients to further control parasites103113, reconstitute the immune system, and maintain high level of CD4+ cell count, hence reducing the incidence of reactivated Chagas’ disease104106.

Trypanosomiasis: African trypanosomiasis

African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) is caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, a haemoflagellate, extracellular and zoonotic protozoan parasite. These two parasite forms exist only in the lymph vessel, bloodstream and the CSF. The clinical course of African sleeping sickness consists of two stages: the early haemolymphatic, trypanosomal chancre and winterbottom's sign, and the CNS (encephalitic) stage, diversity of neurological deficits and severe condition. Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) is a potentially fatal disease and continues to pose a major threat to 60 million people in 36 well defined regions of sub-Saharan Africa where HAT is endemic. It is estimated that there are currently 300,000-500,000 cases, with 50,000 deaths yearly115. It remains unclear whether HIV influences the clinico-epidemiology of HAT although both infections are endemic in sub-Saharan Africa and co-infections are also common116.

Diagnosis: Definite diagnosis is based on the direct detection of trypanosomes from various clinical samples stained smears such as, peripheral blood, CSF or tissue biopsy117. The demonstration of trypomastigotes of T. gambiense is more difficult than T. rhodesiense infections because of low parasite load in the blood as well as CSF samples118. In acute phase, the diagnosis can be done by demonstration of trypanosomes in a chancre or the site bitten by an infected tsetse fly. Microscopic examination is not sensitive to detect the presence of parasites during the late-stage of clinical disease. Serology and molecular (PCR assays) diagnosis are neither sensitive nor specific as compared to direct detection of the parasites through a conventional microscopy. However, a combined method of PCR assays and microscopy is recommended using CSF sample in highly clinical suspicion cases of HAT119.

Neuroimaging diagnosis - In CAT scan, no specific findings have been reported. MRI scan is often used to demonstrate the abnormalities in the brain120: focal high signal abnormalities in the white matter, especially with T2 sequences. This appearance is resolved after treatment121.

Treatment: HAT is a life-threatening disease with high mortality rate (2%-7%) and uniformly fatal if left untreated. Pentamidine, suramin, melasoprol, eflornithine, and benznidazole are the regimen uses for treatment of this parasitic disease. These drugs are recommended once confirmation of diagnosis is achieved. In cases of HAT with confirmed or suspected CNS involvement, melarsoprol should be administered immediately. This agent is potentially effective for both T. gambiense and T. rhodesiense infections, nevertheless, the emergence of melasoprol resistance has been reported122. If melasoprol fails, eflornithine can be used to treat CNS infection by T. gambiense but not effective for T. rhodesiense123. Suramin and pentamidine isethionate are recommended therapies for the early-stage124 and systemic HAT but not effective against CNS infection by T. gambiense and T. rhodesiense125. Moreover, treatment with suramin prevents HIV from penetrating CD4+ T cells and then inhibits reverse-transcriptase activity125. HAT/HIV co-infected patients are at higher risk for treatment failure and unfavourable outcome than seronegative HIV patients126.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) associated with parasitic infections

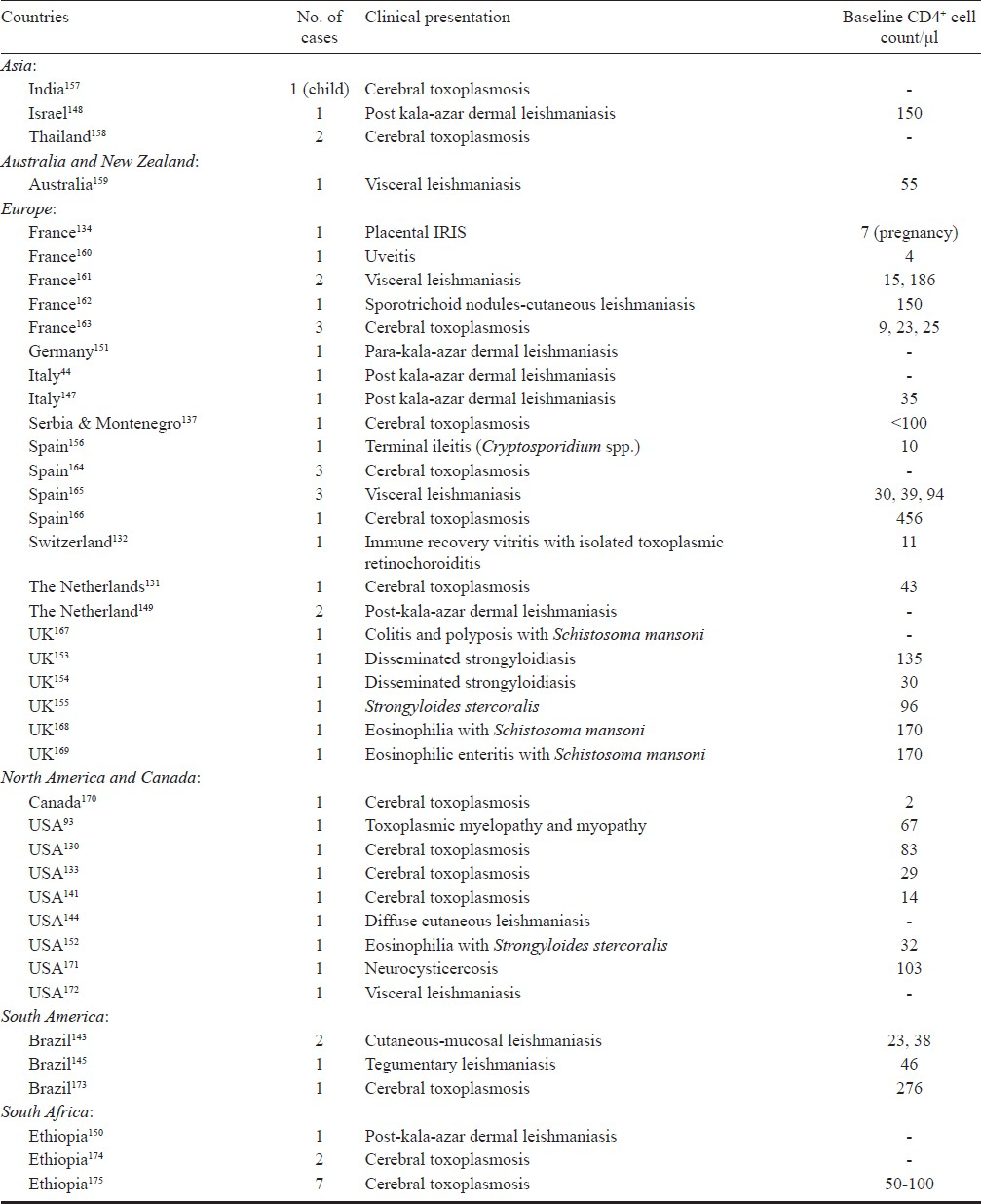

ART partially restores the immune function of HIV-infected patients, thereby remarkably reducing morbidity and mortality of OIs in general and parasitic pathogen in particular. The incidence of parasitic diseases such as leishmaniasis35127, cryptosporidiosis, and toxoplasmosis32128 has been decreased especially in areas where ART, including HAART, is accessible. HAART has significantly reduced secondary reactivation and relapse in cases of toxoplasmosis and has improved survival in these HIV-infected patients. This is certainly due to the successful suppression of virus replications followed by an increase in CD4+ lymphocytes, a partial recovery of T-cell specific immune responses and decreased susceptibility to both local and systemic opportunistic pathogens129. The IRIS constitutes a clinical deterioration of OIs in HIV-infected patients as a result of the enhancement of pathogen-specific immune responses due to the use of HAART. IRIS has been widely recognized in associating with parasitic diseases following initiation of HAART and development of a paradoxical clinical deterioration despite an increased CD4+ cell count and decreased HIV viral load which leads to the rapid restoration of the immune system. So far, more than 20 cases of CT associated IRIS have been reported in the literature (Table). A low CD4+ cell count has been identified as a significant risk factor in AIDS patients with CT93130–134 due to impaired proliferative response to Toxoplasma antigen135, a decreased production of interferon γ136, and IRIS develops more commonly in HIV-infected patients137. Therefore, monitoring of CD4+/CD8+ T cells in patients on HAART might serve as a better marker for the restoration of T. gondii-specific immune responses than the total number of CD4+ cells count138. Immune reconstitution under HAART has been associated with a restoration of immune responses against T. gondii139. In the case w here IRIS is suspected in CT patient, close observation for 7-15 days, a higher steroid dose to control IRIS140, uninterrupted HAART, and continued treatment for toxoplasmosis can resolve this problem without biopsy141. Based on reported cases of CT-associated IRIS from different studies, this could verify its association that it can develop in a substantial numbers of HIV-infected patients receiving HAART. No case of IRIS-related toxoplasmosis has ever been reported among AIDS patients in Malaysia even though CT was one of the most common systemic OIs in AIDS patients78128. The infection with Leishmania spp. occurs anywhere between 10 to 100 times the expected rate, found in patients co-infected with HIV142. Three clinical variations of leishmaniasis with cutaneous findings in association with IRIS have been reported: diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, post-or para-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, sporotrichoid and subcutaneous nodules. The reports of unmasking and paradoxical reactions are also detected in these patients. Diffuse mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (New World disease) has been described in three cases from Brazil and one case in a Nicaraguan immigrant to the USA143–145. From the Old World, seven cases of IRIS-post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis have been reported146–151.

Among intestinal soil-transmitted helminthes, IRIS-associated with strongyloidiasis caused by S. stercoralis has been reported as a new and unexpected presentation in HIV-infected patients. The first case of IRIS-associated strongyloidiasis was reported in a patient with fever, eosinophilia and hepatitis152. Another two cases of disseminated strongyloidiasis were reported in patients with Escherichia coli bacteraemia, eosinophilia and pneumonitis153 and E. coli meningitis154. The fourth case was described in a patient with s0 trongyloides enteritis with thrombocytopenia155. IRIS-associated terminal ileitis caused by Cryptosporidium spp., the first case report of intestinal protozoan infection, was described in a patient with abdominal symptoms of watery, bloodless diarrhoea and epigastric pain156. As for the increasing use of HAART worldwide, the care for patients receiving HAART will need to incorporate monitoring for and treating complications of IRIS including impaired CD4+ cell immune reconstitution upon HIV therapy in patients with opportunistic parasitic infections. In addition, as the number of HIV-associated parasitic diseases cases treated with HAART increases, the complications of IRIS-associated parasitic diseases may become more common and easier to recognize, particularly in areas where tropical parasitic infections are endemic.

Conclusion

POIs remain a major concern in HIV- infected individuals and are unlikely to be eradicated from these patients. Existing parasitic infections still occur in those not yet diagnosed with HIV or not in medical care, those not receiving prophylaxis, and those not taking or not responding to HAART. In addition, there are more emerging POIs such as onchocerciasis or lymphatic filariasis in HIV-infected patients that need to be closely monitored and further studies are recommended to verify any significant association with HIV particularly in tropical areas of endemicity. In most developing countries where ART is fairly limited, HIV-infected patients are certainly at high risk for POIs in general and CT in particular such as in China, India, South America, Southeast Asian region and most importantly sub-Saharan Africa. A better understanding of the clinico-epidemiology of POIs, and improved efforts in prevention, diagnosis and treatment, are urgently needed. The role of OIs with parasites require further studies, including as to whether infections, such as ‘cerebral toxoplasmosis have an impact on HIV/AIDS patients.

Authors thank Michael Benjamin Lane for his assistance and comments of this manuscript. This work was financially supported by the University of Malaya Research Grant (UMRG 094/09HTM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, for presenting in part at the Joint International Tropical Medicine Meeting (JITMM), Bangkok, Thailand, 1-2 December 2011. Authors are grateful to Prof. Prayong Radomyos, Mahasarakham University, Thailand for providing Figs 1 and 2; Dr Orrasa Rattanasinchaiboon and Dr Sucheep Piriyasmith, Kasem Bandit University, Thailand for Fig. 3; and Dr Pisud Siripaitoon, Songklanagarind Hospital, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand for Fig. 4.

References

- UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010 [homepage on the Internet]. Epidemic update. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_Chap2_em.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Revision of the CDC surveillance case definition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. MMWR Surveill Summ. 1987;36:1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among HIV patients in Benin City, Nigeria. 2010; 5 -doi: 10. Libyan J Med. 2010;5 doi: 10.3402/ljm.v5i0.5506

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of intestinal parasitic pathogens in HIV-seropositive individuals in Northern India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:83-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of infections with intestinal parasites and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among sugar-estate residents in Ethiopia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2000;94:269-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal parasitic infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative individuals in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:431-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- First detection of intestinal microsporidia in Nigeria. Online J Health All Sci. 2005;3:4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opportunistic parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS patients presenting with diarrhoea by the level of immunesuppression. Indian J Med Res. 2009;131:63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- How common is intestinal parasitism in HIV-infected patients in Malaysia? Trop Biomed. 2011;28:400-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pravalence and impact of diarrhea on health-related quality of life in HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:484-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isosporiasis in patients with HIV infection in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era in France. HIV Med. 2008;9:126-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Etiology of chronic diarrhea in antiretroviral-naive patients with HIV infection admitted to Norodom Sihanouk Hospital, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:925-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal parasitic infections in Thai HIV-infected patients with different immunity status. BMC Gastroenterol. 2001;1:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-infected children with acute and chronic diarrhea. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2001;32:33-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal microsporidiosis in HIV-infected children with diarrhea. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33:241-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging microsporidian infections in Russian HIV-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2102-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amebiasis among persons who sought voluntary counseling and testing for human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case-control study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:65-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in HIV-Infected patients in China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:825-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amebiasis among persons who sought voluntary counseling and testing for human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case control study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:65-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics of amebic liver abscess in patients with or without human immunodeficiency virus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2009;42:500-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of clinical characteristics of amebic liver abscess in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected patients. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008;41:456-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of giardiasis and stronglyloidiasis among HIV-infected patients in Bahia, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2001;5:339-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal parasitic infections in HIV/AIDS and HIV seronegative individuals in a teaching hospital, Ethiopia. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:41-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giardiasis in HIV: A possible role in patients with severe immune deficiency. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:485-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemotherapy of protozoal infections: Amebiasis, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, trypanosomiasis, leishmaniasis, and other protozoal infections. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (12th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

- [Google Scholar]

- Difficulties in the treatment of intestinal amoebiasis in mentally disabled individuals at a rehabilitation institution for the intellectually impaired in Japan. Chemotherapy. 2010;56:348-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cryptosporidiosis occurrence in anti-HIV-seropositive patients attending a sexually transmitted diseases clinic, Thailand. Trop Doct. 2006;36:64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kala-azar outbreak in Libo Kemkem, Ethiopia: epidemiologic and parasitologic assessment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:275-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:334-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leishmania major and HIV co-infection in Burkina Faso. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2003;97:168-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leishmania/HIV co-infection in Brazil: an appraisal. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97(Suppl 1):17-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of rk39 immunochromatographic test with urine for diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:537-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis after visceral disease in a patient with AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:461-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47:349-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis as an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a patient with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1032-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopian visceral leishmaniasis: generic and proprietary sodium stibogluconate are equivalent; HIV co-infected patients have a poor outcome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:668-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent understanding in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:61-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relapse of visceral leishmaniasis in patients who were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus and who received treatment with liposomal amphotericin B. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:560.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2009. Reported malaria cases and deaths [cited 2011 Aug 25] Available from: http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2010/wmr2010_annex7a.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and malaria interaction in sub-Saharan Africa: the collision of two Titans. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8:246-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of the accuracy of the ParaSight-F test in the diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:MT81-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adult cerebral malaria: prognostic importance of imaging findings and correlation with postmortem findings. Radiology. 2002;224:811-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postmalaria neurological syndrome: a case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:388-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2008. Essential prevention and care interventions for adults and adolescents living with HIV in resource-limited settings. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/OMS_EPP_AFF_en.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurocysticercosis: updated concepts about an old disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:653-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parasitic central nervous system infections in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1005-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical management of neurocysticercosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:2845-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Expert Committee. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2002;912:i-vi.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of schistosomiasis in African patients infected with HIV. HIV Med. 2008;9:436-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Schistosomiasis mansoni and severe gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:379-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurological complications of Schistosoma infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:107-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Involvement of central nervous system in the schistosomiasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99(5 Suppl 1):59-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunodiagnosis and its role in schistosomiasis control in China: a review. Acta Trop. 2005;96:130-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serodiagnosis of imported schistosomiasis by a combination of a commercial indirect hemagglutination test with Schistosoma mansoni adult worm antigens and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with S. mansoni egg antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3432-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of corticosteroids in the treatment of cerebral schistosomiasis caused by Schistosoma mansoni: case report and discussion. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:47-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristic magnetic resonance enhancement pattern in cerebral schistosomiasis. Chin Med Sci J. 2006;21:223-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of oxamniquine and praziquantel in the treatment of Schistosoma mansoni infection: a controlled trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:190-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Schistosoma japonicum: effect of artemether on glutathione S-transferase and superoxide dismutase. Exp Parasitol. 2002;102:38-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Resistance to reinfection with Schistosoma mansoni in occupationally exposed adults and effect of HIV-1 co-infection on susceptibility to schistosomiasis: a longitudinal study. Lancet. 2002;360:592-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis and HIV: a case report of an indigenous disseminated infection from non-endemic area. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2006;38:137-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why does HIV infection not lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis? J Infect Dis. 2004;190:2175-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis in the Immunocompromised Population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxoplasmosis in HIV/AIDS patients: a current situation. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2004;57:160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- AIDS-associated toxoplasmosis. In: Sande MA, Volberding PA, eds. The medical management of AIDS. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992. p. :319-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Opportunistic parasitic diseases and mycoses in AIDS.Their frequencies in Brazzaville (Congo) Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1988;81:311-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients in Brazil: importance of molecular and immunological methods using peripheral blood samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5044-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis in HIV-positive patients in Brazil: clinical features and predictors of treatment response in the HAART era. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:626-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxoplasma gondii infection and cerebral toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients. Future Microbiol. 2009;4:1363-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxoplasma gondii. In: Walzer PD, Gertz R, eds. Parasitic infection in the compromised host. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1989. p. :179-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of two DNA targets for the diagnosis of Toxoplasmosis by real-time PCR using fluorescence resonance energy transfer hybridization probes. BMC Infect Dis. 2003;3:7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation and management of intracranial mass lesions in AIDS: Report of the Quality Standard Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 1998;51:1233-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stereotactic brain biopsies in AIDS patients-early local experience. Singapore Med J. 2000;41:161-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of intracerebral lesions in patients with HIV: a retrospective study with discussion of diagnostic problems. QJM. 1998;91:205-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stereotactic brain biopsy in AIDS patients: a necessary patient-oriented and cost-effective diagnostic measure? Acta Med Austriaca. 1998;25:91-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ventriculitis: a rare case of primary cerebral toxoplasmosis in AIDS patient and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2008;12:101-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neurological complications of HIV infection. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:297-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxoplasmosis myelopathy and myopathy in an AIDS patient: a case of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome? Neurologist. 2011;17:49-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized phase II trial of atovaquone with pyrimethamine or sulfadiazine for treatment of toxoplasmic encephalitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: ACTG 237/ANRS 039 Study. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 237/Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA, Essai 039. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1243-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chagas disease: what is known and what is needed--a background article. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(Suppl 1):113-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Congenital transmission of Chagas disease in Latin American immigrants in Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:601-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumour-like chagasic encephalitis in AIDS patients: an atypical presentation in one of them and outcome in a small series of cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:881-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chagasic meningoencephalitis: case report of a recently included AIDS-defining illness in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2004;46:199-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reactivation of Chagas disease with central nervous system involvement in HIV-infected patients in Argentina, 1992-2007. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:587-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Some aspects of protozoan infections in immunocompromised patients - a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:443-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chagasic encephalitis in HIV patients: common presentation of an evolving epidemiological and clinical association. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:324-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular diagnosis and typing of Trypanosoma cruzi populations and lineages in cerebral Chagas disease in a patient with AIDS. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:1016-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Central nervous system involvement in Chagas disease: a hundred-year-old history. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:973-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Empirical anti-toxoplasma therapy in cerebral AIDS and Chagas disease. Presentation of 2 cases, review of the literature and proposal of an algorithm. Medicina (B Aires). 1998;58:504-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of nonenteric protozoan infections in immunocompromised people. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:795-836.

- [Google Scholar]

- Using polymerase chain reaction in early diagnosis of re-activated Trypanosoma cruzi infection after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23:1345-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Usefulness of PCR strategies for early diagnosis of Chagas’ disease reactivation and treatment follow-up in heart transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1633-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a real-time PCR assay for Trypanosoma cruzi detection in blood samples. Acta Trop. 2007;103:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prolonged survival and immune reconstitution after chagasic meningoencephalitis in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:85-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exacerbation of HIV viral load simultaneous with asymptomatic reactivation of chronic Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67:521-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The continuing problem of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) Ann Neurol. 2008;64:116-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV-1 replication in monocyte-derived dendritic cells is stimulated by melarsoprol, one of the main drugs against human African trypanosomiasis. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:1052-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC. In: Laboratory diagnosis of parasites of public health concern. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2003.

- [Google Scholar]

- The challenge of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness diagnosis outside Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:804-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stage determination and follow-up in sleeping sickness. Med Trop (Mars). 2001;61:355-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human African trypanosomiasis of the CNS: current issues and challenges. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:496-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging findings in African trypansomiasis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1383-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei spp., the causative agents of sleeping sickness in man and nagana in cattle. Microbes Infect. 2001;3:763-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current chemotherapy of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitol Res. 2003;90(Supp 1):S10-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment perspectives for human African trypanosomiasis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:171-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arsenicals (melarsoprol), pentamidine and suramin in the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:71-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical description of encephalopathic syndromes and risk factors for their occurrence and outcome during melarsopol treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:390-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of and risk factors for symptomatic visceral leishmaniasis among human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients from Spain in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:762-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- AIDS-defining illnesses: a comparison between before and after commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Curr HIV Res. 2007;5:484-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly active antiretroviral therapy access and neurological complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection: impact versus resources in Brazil. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(Suppl 3):11-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case report.Toxoplasma encephalitis after initiation of HAART. AIDS Read. 2001;11:608-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune recovery vitritis in an HIV patient with isolated toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. AIDS. 2006;20:2237-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fetal death as a result of placental immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Infect. 2010;61:185-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and risk factors of toxoplasmosis in a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: 1988-1995. HEMOCO and SEROCO Study Groups. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:575-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decreased short-term production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive subjects. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1507-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and risk of immune restoration disease in HIV-infected patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2005;6:140-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Restoration of Toxoplasma gondii-specific immune responses in patients with AIDS starting HAART. AIDS. 2008;22:2087-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune recovery under highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with restoration of lymphocyte proliferation and interferon-gamma production in the presence of Toxoplasma gondii antigens. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1586-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in the CNS of HIV-infected patients. Neurology. 2006;67:383-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The immune inflammatory reconstitution syndrome and central nervous system toxoplasmosis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:656-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leishmania/HIV co-infections: epidemiology in Europe. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2003;97(Suppl 1):3-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tegumentary leishmaniasis as a manifestation of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in 2 patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1819-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis associated with the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1263-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tegumentary leishmaniasis as the cause of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a patient co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus and Leishmania guyanensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:559-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis during highly active antiretroviral therapy in an AIDS patient infected with Leishmania infantum. J Infect. 2000;40:199-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis manifesting after initiation of highly active anti-retroviral therapy in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:451-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful miltefosine treatment of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis occurring during antiretroviral therapy. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100:223-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leishmaniasis (PKDL) as a case of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in HIV-positive patient after initiation of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) Ethiop Med J. 2009;47:77-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical isolate of Leishmania donovani with ITS1 sequence polymorphism as a cause of para-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in an Ethiopian human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:870-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis infection as a manifestation of immune restoration syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:439-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloidiasis in an HIV-1-infected patient after highly active antiretroviral therapy-induced immune restoration [letter] J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1027.

- [Google Scholar]

- Schistosoma mansoni, nematode infections, and progression to active tuberculosis among HIV-1-infected Ugandans. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:819-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune reconstitution syndrome to Strongyloides stercoralis infection. AIDS. 2007;21:649-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Terminal ileitis as a manifestation of immune reconstitution syndrome following HAART. AIDS. 2006;20:1903-5.

- [Google Scholar]