Translate this page into:

Diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica usually means a favourable outcome for your patient

Reprint requests: Dr. Marcin Milchert, Department of Rheumatology, Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, ul Unii Lubelskiej 1, 71-252 Szczecin, Poland e-mail: marcmilc@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a unique disease of elderly people, traditionally diagnosed based on a clinical picture. A typical case is a combination of severe musculoskeletal symptoms and systemic inflammatory response with spectacular response to corticosteroids treatment. The severity of symptoms may be surprising in older patients where immunosenescence is normally expected. However, PMR may be diagnosed in haste if there is a temptation to use this diagnosis as a shortcut to achieve rapid therapeutic success. Overdiagnosis of PMR may cause more problems compared to underdiagnosis. The 2012 PMR criteria proposed by European League against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology aim to minimize the role of clinical intuition and build on more objective features. However, questions arise if this is possible in PMR. This has been discussed in this review.

Keywords

Classification criteria

corticosteroids

diagnosis

musculoskeletal

polymyalgia rheumatica

Introduction

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an auto-inflammatory rheumatic disease of people over 50 years, presenting with pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulder and hip girdles1. The term PMR was first used to underline that it seemed substantially milder from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) as no joint damage had been observed2. However, this name may be misleading as PMR is a disease but not a non-specific myalgic or paraneoplastic syndrome. Secondary PMR does not exist. The short definition of PMR may be also misunderstood as it does not suggest how unique the clinical picture of ‘musculoskeletal pain and stiffness’ might be. What makes PMR so special is a sudden onset of severe musculoskeletal symptoms that strongly reduce daily performance and quality of life, together with systemic inflammatory reaction in elderly but usually generally healthy patient, frequently accompanied by depressive reaction, lack of pathognomonic laboratory or radiologic findings, and splendid reaction to low-dose corticosteroids (CSs). Strong auto-inflammatory response is normally unexpected in an elderly patient, but immunosenescence3 seems not to apply in PMR. Good prognosis is also surprising as there is no good explanation to the fact that PMR patients apparently live longer than matched controls45. However, PMR is frequently accompanied by giant cell arteritis (GCA). Therefore, there is an increased probability of all the ischaemic complications related to GCA in PMR6. Further, generally favourable outcome of PMR may be easily wasted in case of excessive CSs treatment, resulting in side effect that eventually worsens patient's quality of life7.

The aim of this review article is to discuss about correct diagnosis of PMR.

Epidemiology

Annual incidence of PMR is up to 50/100,000 population over 50 yr5. It is uncommon in India89. The highest prevalence is found in Caucasians, in Northern European countries, especially in Scandinavia. Vikings' ancestry is associated with increased risk of PMR (marked by migration from Scandinavia10, in Western European lands invaded by Normands11 or Eastern European settled by Varangians12). The incidence grows with age, starting from 50 yr, with peak above 70 yr5. It is easier to find a report of wrong diagnosis of PMR in patients under 50 yr13, than an undoubtful case report of PMR or GCA in young14.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica Versus Giant Cell Arteritis

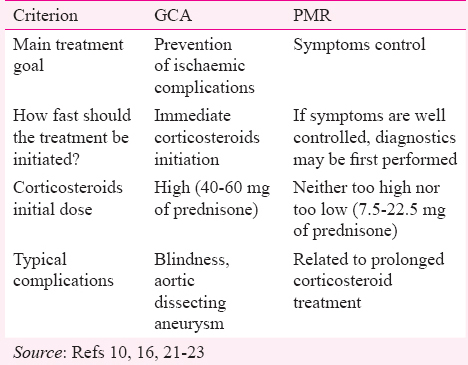

PMR and GCA are closely related. These have similar genetic background and epidemiology, and frequently overlap15. However, PMR represents a non-specific immune-mediated inflammatory reaction triggered by innate immunity activation. GCA is manifested by vascular inflammation caused by faulty adaptive immune reaction that is mainly T cell dependent16. The clinical outcome is so different that it is continuously debated why some patients express only one pathway. Evidence of vascular inflammation in needed to diagnose GCA. It is usually recorded in about 10 per cent of PMR patients17, but detailed vascular examination may substantially increase that percentage18. The historical term polymyalgia arteritica19 might still be accurate because it underlines suspected vascular pathogenesis of PMR. Silent vasculitis has been demonstrated in some of PMR patients20. Regardless of PMR and GCA pathophysiologic relations, from a practical point of view, it must not be forgotten that patients diagnosed with PMR are also at an increased risk of GCA-associated complications. The concomitant GCA implies the need for more aggressive treatment strategy (Table I). PMR symptoms can dominate over the clinical picture of GCA. Small CSs doses used for PMR do not suppress concomitant GCA (although this is more generally accepted than proved opinion)21 that may progress to cause blindness.

When Should Polymyalgia Rheumatica Be Suspected?

Proximal, musculoskeletal pain and stiffness are the leading manifestations and these raise little doubts about the diagnosis in a typical PMR case. However, PMR pivotal manifestations may be less specific: fewer or raised C-reactive protein (CRP) of unknown origin, general weakness, weight loss, depressive reaction, decompensation of chronic diseases (e.g. chronic heart failure) due to increased metabolism121.

How to Diagnose Polymyalgia Rheumatica?

There is no universal answer to this question. Although clinical presentation is typical, in some cases, the disease may be surprising. The best strategy is a combination of different approaches (based on clinical picture, classification criteria, exclusions and ex juvantibus diagnosing), together with extensive diagnostics and follow up observation of atypical cases24. Ninety per cent of rheumatologists in the United Kingdom (UK) declare the use of the classification criteria for PMR diagnosis although they admit not to adhere to the guidelines to exclude other diseases25. This approach may be accepted only in countries with high incidence of PMR resulting in relatively low number of PMR mimics26.

Diagnosis Based on Clinical Picture

Clinical assessment is most important for PMR diagnosis. There are no specific antibodies (PMR and GCA are T cell-dependent diseases1627) or additional testing to confirm PMR. Clinical manifestations come from a combination of musculoskeletal pain and stiffness and acute inflammatory response, which is quite different in elderly compared to young patients.

Musculoskeletal manifestations

It is difficult to find PMR case without bilateral pain and stiffness of muscles and joints of neck, shoulder and hip girdles. Generalized musculoskeletal pain is not a PMR manifestation. Small joints involvement is also not typical but may be rarely found28. Shoulder girdle involvement usually appears first and may gradually extend to the area of neck and hip girdle. Symmetrical involvement is typical. The pain worsens during the night, typically waking the patient from sleep between 0400 and 0600 h in the morning. Morning stiffness of more than one hour is more specific for PMR than the pain, but the pain is more commonly reported. Pain may overwhelm the symptoms of stiffness. Limitations of upper limbs elevation make it difficult for the patient to comb his/her hair or pray in the morning. It is illustrated by the way patients get up out of bed: large joints stiffness makes them to rock the whole body to slip out beyond the edge of bed. However, after overcoming morning stiffness, patients can usually perform their daily activities fairly well. The feeling of stiffness can also reoccur during the day, after a period of immobility. In extreme cases, musculoskeletal stiffness may cause even a daylong immobilization. However, the course may also be self-limiting. Patients report limb weakness by which they understand the limitation of motion due to stiffness and pain. In contrast with polymyositis, PMR does not cause actual muscle weakness2429. Bilateral tenderness of proximal muscles is a valuable sign both for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

Manifestations associated with inflammatory response or deterioration of general state

It is surprising in PMR patient as to how intense inflammatory reaction in elderly may manifest. However, it is also possible to cause anergy-like state with depressive reaction and cachexia. In both situations, PMR may be confused with symptoms of premature ageing both by patients and their physicians30. Acute or sub-acute onset of the disease (up to 2 wk) is characteristic, which means a sudden deterioration of daily performance and reduced quality of life. It may appear striking in an older patient who was previously coping well with his/her daily activities. Depressive reaction may be the first or the leading manifestation. Inflammatory reaction in elderly can manifest atypically, by reduction of psychomotor activity and decreased appetite. They can be difficult to differentiate from the endogenous depression. Pro-depressive characteristics of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which plays substantial role in PMR pathogenesis31, should be taken into account for a better explanation of this phenomenon32. Another reason for behavioural change in PMR patients may be an adaptive response associated with rapid deterioration of physical performance, causing anxiety of getting old and loosing self-reliance33. Weight loss is a common manifestation and may progress severely. Low-grade fever and night sweats may persist for months. Patients describe it as ‘a flu that does not go away’243435.

Atypical presentations

These are possible but frequently remain controversial. These include atypical musculoskeletal manifestations (distal or asymmetrical joints involvement, sternoclavicular joints involvement, lack of shoulder girdle involvement, lack of morning stiffness), younger age at the disease onset, normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP serum levels, lack of good response to CSs treatment2324.

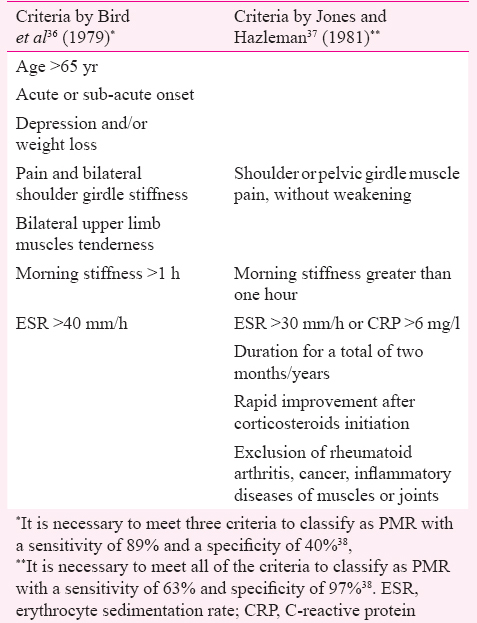

Diagnosis Based on the Classification Criteria

Classification criteria are not developed for diagnosing but are generally used for this purpose. Systems of classification of the diseases are demanded by clinical trials, public health and insurance systems. These criteria define most typical manifestation of the disease and provide an organized summary of its main manifestations. That is why the ‘old’ criteria such as formulated by Bird et al36 or Jones and Hazleman37 are still valid as these were formulated based on clinical observation (Table II). Yet, PMR is not a disease diagnosed by simple ticking signs and symptoms on a checklist. If it were so, a coincidence of depression and shoulder joints osteoarthritis (OA) in an elderly patient would be misclassified as PMR according to Bird's criteria. The interpretation of the importance of complaints and findings in an individual patient by an expert remains fundamental for PMR diagnosis. Shoulder girdle pain must have inflammatory character and depression cannot be endogenous to be accounted in Bird's criteria. Jones and Hazleman's criteria have a potential superiority in countries with low PMR prevalence as they have a higher specificity and include a list of most important exclusions.

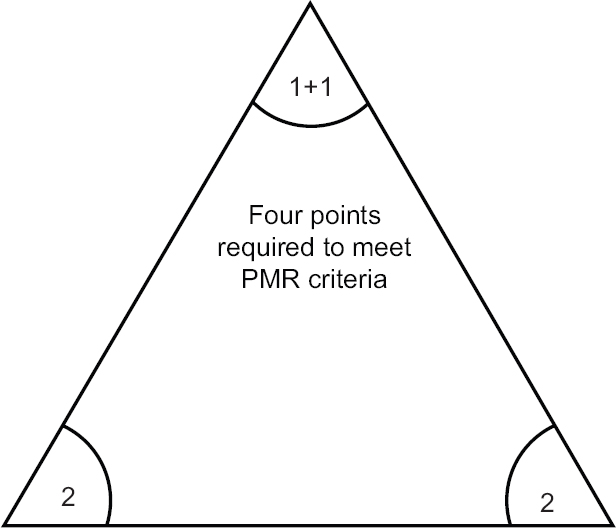

In 2012, European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) formulated new classification criteria for PMR (Fig. 1)3839. These may only be applied in patients meeting preliminary criteria: age over 50 yr, bilateral shoulder aching, elevated CRP or ESR. These are a good example of classification philosophy to reduce heterogeneity of positively classified cases by selecting the subset of the most typical manifestations. Therefore, these criteria are not to be met in atypical cases of PMR. On the other hand, these have a potential to reduce the rate of false positive diagnosis38.

- Patient meeting preliminary criteria must score at least 4 points to be classified as polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) according to European League against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology criteria39, which gives three possible scenarios encompassing the combination of 2 points for morning stiffness; 2 points for absence of rheumatoid arthritis specific antibodies; 1+1 point for hip girdle involvement and absence of other joint involvement. Source: Ref 39.

Ultrasound

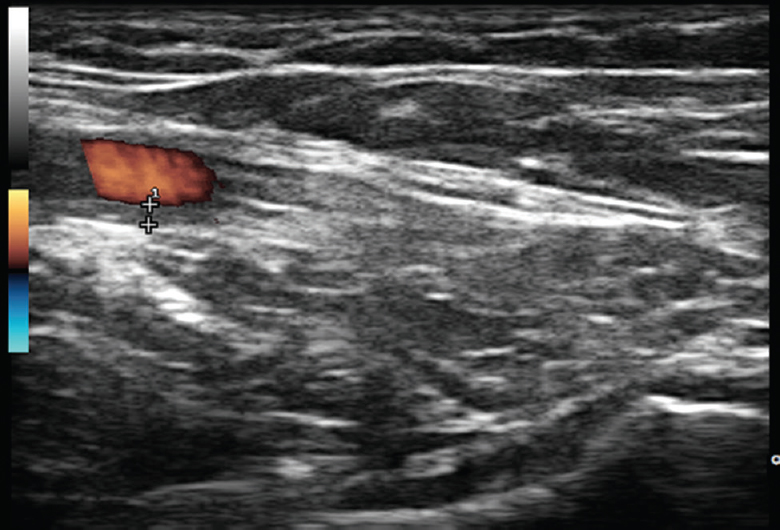

Musculoskeletal ultrasound gains importance in rheumatology. PMR criteria integrated ultrasonographic evaluation into classification process for the first time in rheumatology39. Ultrasound criterion requires examining both shoulders (for glenohumeral synovitis, bursitis or biceps tenosynovitis) and hips (for joint synovitis or trochanteric bursitis). The intention for this is assessment of the symmetry of changes between inflammatory changes in both shoulders and between upper and lower limbs involvement. Each of these will score an additional point to the scoring algorithm. Final sum of five out of eight (6 from algorithm without ultrasound plus 2 from ultrasound examination) points enables to classify a patient as PMR with 66 per cent sensitivity and 81 per cent specificity39. Ultrasound evaluation is relatively simple to perform as the findings of merely the presence of joint effusion, tenosynovitis or bursitis are sufficient. However, these abnormalities are hardly specific for PMR. A short ultrasound examination of proximal joints usually fails to demonstrate differences between inflammatory joint diseases. The differentiation between PMR and RA is a common dilemma. A more detailed ultrasound assessment can demonstrate joints' erosions and extensive synovial proliferation of both small and large joints that are more typical for RA. Ultrasound can demonstrate degenerative or post-traumatic joint lesions as well as detect GCA overlap40 (Fig. 2).

- Ultrasound examination of glenohumeral joint from axillary approach revealing no significant effusion inside a joint capsule (bottom of the picture). With the same approach, axillary artery is simultaneously examined with colour duplex ultrasound (left, upper side of the picture): it reveals homogenous, hypoechoic vessel wall thickening of 1 mm (indicated between “+” signs), well delineated towards the luminal side being consistent with axillary arteritis.

Additional tests to help with the diagnosis

There are no pathognomonic antibodies or other PMR-specific markers discovered. Although ESR and CRP serum levels are not specific, it is hard to find PMR with normal inflammatory parameters41. Other acute phase markers (fibrinogenemia, thrombocythemia and elevated IL-6, the latter correlates best with the disease activity42) are also present. Anaemia of chronic disease type is common and is reversed shortly after CSs treatment initiation. Sometimes, slightly increased transaminases and alkaline phosphatase levels are present. Sparse studies indicated a significantly higher occurrence of anti-phospholipid antibodies, but these have not been proved to be associated with ischaemic or thromboembolic complications42434445.

The benefits and drawbacks of classification criteria sets must be duly considered before applying them for diagnosis. The 2012 proposed EULAR/ACR PMR criteria38 (opposed to the previous sets) aim to minimize the role of clinical intuition and build on more objective features and additional tests. However, ESR, rheumatoid factor and ultrasound changes still have only limited specificity. The drawbacks of all of the PMR criteria sets are their unsatisfactory sensitivity and specificity. They were also formulated in populations with a high PMR prevalence. If classification criteria are not met (which usually takes place in atypical PMR), the disease should not be diagnosed hastly but only after excluding other causes of similar symptoms2324.

Diagnosis by Excluding Other Causes of Similar Symptoms

The need for considering PMR exclusions was underlined in the previous criteria37 and is also found in the current guidelines23. The typical clinical picture of PMR requires only basic differential diagnostics. The more atypical the clinical picture, the wider differential diagnostics is required. The differential diagnostics in countries with low PMR incidence requires considering the relatively higher number of PMR mimics. It was illustrated in a study from Turkey that 30 per cent of patients with final PMR diagnosis were hospitalized, 30 per cent were treated with antibiotics, and in 29, 22 and 19 per cent abdominal, chest and brain computed tomography (CT), respectively, were performed. This approach seemed reasonable; however, there were still 13±13 months delay from onset of symptoms to diagnosis46.

Why do PMR-like manifestations mask the symptoms of other diseases? PMR pathogenesis is mediated by innate immunity. It triggers non-specific inflammatory reaction which is not unique for PMR47. Acute inflammatory response can mask more characteristic symptoms of a disease that are not reported by patients. For example, elderly onset RA may go with systemic inflammatory manifestations and large joint involvement that cause patient immobilization. Therefore, small joints inflammation is not reported by a patient whose main complaint is inability to get out of bed. Further, serious, GCA-associated ischaemic manifestations (such as double vision or jaw claudication that are typical prodromal symptoms of vision loss) can be unreported by patients seeking medical advice because of much more disturbing manifestations of overlapping PMR. Paraneoplastic syndromes that can be manifested long before an appearance of symptoms associated with tumour growth may also be misclassified as PMR48.

Differential diagnosis of conditions associated with musculoskeletal symptoms

Differentiation between PMR and seronegative, elderly onset RA affecting proximal joints is actually a common reason for diagnostic uncertainty. It may also be a case if bilateral painful shoulder syndrome coexists with depression and elevated ESR. Ultrasound examination of the shoulder joints may be helpful in determining the cause of the pain. Diagnosing the sources of inflammatory reaction and mood disorders in the elderly may be demanding, requiring knowledge on geriatrics. Musculoskeletal symptoms resembling PMR may originate from myopathy due to hypo- or hyperthyroidism, CSs or statins use, amyloidosis; Addison's disease (also adynamia suggesting depression and a good response to CSs)4950.

Differential diagnosis of conditions associated with inflammatory response or deterioration of general state

Typical PMR age group is associated with a high risk of cancer. Manifestations of PMR may also resemble paraneoplastic syndromes. However, PMR frequently starts suddenly and manifests more dynamically. Spontaneous remission, which can occur in PMR, is unusual for cancer. A 1.7-fold increase in the rate of cancer diagnoses was noted in the first six months of PMR observation in the UK, compared to age- and sex-matched patients with no PMR51. Attempts should be made to minimize this period by differential diagnostics and careful observation of atypical PMR cases48. Some of the PMR symptoms (fever, night sweats and joint pain) may suggest systemic lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases, including endocarditis or tuberculosis. Focus on musculoskeletal pain can mask the endogenous or reactive depression being the real cause of deterioration of patient's state.

Due to PMR and GCA overlap, physical examination of PMR patients should encompass temporal arteries (for tenderness, loss of pulsation) and large arteries analogically to Takayasu arteritis (upper and lower limbs intermittent claudication, differences in blood pressure between both limbs, presence of vascular bruits). Treatment-resistant PMR indicates a special need for imaging of large arteries for overlapping vasculitis. It may include ultrasound examination of temporal and large (axillary, sub-clavian, common carotid) arteries by a specialist experienced in differentiating vascular wall inflammation from arteriosclerosis, as well as assessment of the aorta and its branches with contrasted computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) with CT5253. Lack of GCA manifestations at the time of PMR diagnosis should not stop the awareness of developing vasculitis during follow up. Small CSs doses used for PMR do not protect against the progression of arterial inflammation54. PMR patients should be educated to immediately seek medical advice in case of vision disturbance (double vision, transient ischaemic attacks), jaw claudication or scalp tenderness.

Diagnosis ex juvantibus

Rapid and spectacular improvement shortly after CSs introduction enables concluding on a cause based on an observed response to the treatment. Therefore, PMR patients are much pleased shortly after treatment initiation and grateful to their doctors55. Lack of improvement within five days suggest a need to verify the PMR diagnosis (to some different disease or GCA)22. Diagnosis ex juvantibus was included in Jones and Hazleman's criteria37. New, 2012 PMR classification criteria do not include a good response to CSs in the diagnostic process39. It raised some discussion as this criterion is widely used in a daily practice56. It was argued that treatment response was non-specific and difficult to define feature. Indeed, elderly onset RA or other inflammatory conditions also respond well to CSs. However, this response would be weak in OA and transient if applied in infection or neoplasm. In these cases review of the initial PMR diagnosis is needed. It is not a mistake to reassess the initial diagnosis and change it accordingly. About 10 per cent of patients initially diagnosed with PMR are later reclassified as having elderly onset RA57. For that purpose, careful monitoring of patients is needed. PMR patients require regular medical check-ups.

Diagnosing ex juvantibus may also be made eagerly because it does not require an effort of time-consuming and expensive procedures. Spectacular efficacy of CSs in PMR may cause a temptation to overuse them. There has been increased interest in GCA and PMR evoked by modern treatment possibilities5859 and fast track GCA clinics60. Based on our own experience, PMR is easy to overdiagnose. Establishing rational PMR diagnosis illustrates a challenge to resist fashion and wishful thinking in medicine. Adherence to the 2012 PMR classification criteria could be beneficial in preventing overdiagnosis because these do not include response to therapy. However, the ‘response criterion’ will not disappear from the daily practice of the physicians who can appreciate how unique PMR symptoms react to CSs. At least as long as there are no better disease markers.

Conclusion

Lack of specific biomarkers of PMR is problematic and research is needed. Up to now, the diagnosis remains clinical. There are many clinical subtleties to be considered. Usually, PMR responds well to CSs treatment and outcomes are favourable. However, differential diagnosis encompasses diseases with bad prognosis; therefore, PMR overdiagnosis can be detrimental.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Polymyalgia rheumatica – Diagnosis and classification. J Autoimmun. 2014;48-49:76-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myalgic syndrome with constitutional effects; polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:230-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Local and systemic immune response in nursing-home elderly following intranasal or intramuscular immunization with inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2003;21:1180-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Causes of death in polymyalgia rheumatica. A prospective longitudinal study of 315 cases and matched population controls. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:38-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of polymyalgia rheumatica in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1970-1991. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:369-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica and the risk of cerebrovascular accident. Neurol India. 2016;64:912-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse outcomes of antiinflammatory therapy among patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1873-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temporal arteritis: A case series from south India and an update of the Indian scenario. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:27-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: A population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3522-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica: 125 years of epidemiological progress? Scott Med J. 2015;60:50-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does Viking ancestry influence the distribution of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis in Poland? Scand J Rheumatol. 2016;45:536-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia revealing eosinophilic fasciitis in a young male: Contribution of magnetic resonance imaging. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:367-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temporal arteritis in a young patient. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(3 Suppl 82):S59-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis the same disease? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;33:294-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival in polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis: A study of 398 cases and matched population controls. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:1238-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- (18)F-FDG PET/CT for the detection of large vessel vasculitis in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2015;34:275-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: Challenges, controversies and practical tips. Postgrad Med J. 2013;89:284-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2015 Recommendations for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1799-807.

- [Google Scholar]

- BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:186-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica: Clinical presentation is key to diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:489-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Balancing on the edge: Implications of a UK national audit of the use of BSR-BHPR guidelines for the diagnosis and management of polymyalgia rheumatica. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000095.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:891-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes expressing CD161 are implicated in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3788-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peripheral joint involvement in polymyalgia rheumatica: A clinical study of 56 cases. Br J Rheumatol. 1985;24:27-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- “An impediment to living life”: Why and how should we measure stiffness in polymyalgia rheumatica? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126758.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR) Special Interest Group at OMERACT 11: Outcomes of importance for patients with PMR. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:819-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis and implications for treatment. Cytokine. 2008;44:207-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis of differences in IL-6 and IL-10 between people with and without depression: Exploring the causes of heterogeneity. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1180-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Musculosceletal diseases and involutional changes. In: Żakowska-Wachelko B, ed. Geriatric medicine outline [Zarys medycyny geriatrycznej]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2000. p. :147.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica – Clinical observations on 90 patients. Z Rheumatol. 1985;44:218-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of 287 patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis: Clinical and laboratory manifestations at onset of disease and at the time of diagnosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1161-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- An evaluation of criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979;38:434-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of the new 2012 EULAR/ACR classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: Comparison with the previous criteria in a single-centre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1190-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2012 provisional classification criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:484-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of musculoskeletal imaging for the diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica: Systematic review. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica with low erythrocyte sedimentation rate at diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1333-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum markers associated with disease activity in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1397-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum cytokines and steroidal hormones in polymyalgia rheumatica and elderly-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1438-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticardiolipin antibodies in giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: A study of 40 cases. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:208-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The process from symptom onset to rheumatology clinic in polymyalgia rheumatica. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34:1589-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica mimicking neoplastic disease – Significant problem in elderly patients. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2008;118(Suppl 1):47-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymyalgia rheumatica in primary care: Managing diagnostic uncertainty. BMJ. 2015;351:h5199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recognition and management of polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:676-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is cancer associated with polymyalgia rheumatica? A cohort study in the General Practice Research Database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1769-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: Usefulness of vascular magnetic resonance imaging studies in the diagnosis of aortitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:479-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Various forms of (18)F-FDG PET and PET/CT findings in patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2015;159:629-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Provisional diagnostic criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica: Moving beyond clinical intuition? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:475-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcome of 149 patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:99-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interleukin 6 blockade as steroid-sparing treatment for 2 patients with giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2080-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with giant cell arteritis: Primary and secondary outcomes from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [Abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10):1204-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of ultrasound in the understanding and management of vasculitis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2014;6:39-47.

- [Google Scholar]