Translate this page into:

Sickle cell disease in India: A perspective

* For correspondence: grserjeant@cwjamaica.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood condition which is most common among people of African, Arabian and Indian origin. In disease of African origin, research has led to models of care which prevent serious complications, improve the quality of life, and increase survival1. In India, the disease is largely undocumented. Thus, there is an urgent need to document the features of Indian disease so that locally appropriate models of care may be evolved.

The sickle cell mutation affects the beta chain of adult haemoglobin which changes the behaviour of sickle cell haemoglobin. Possession of a single HbS gene results in the generally harmless sickle cell trait (AS genotype) but inheritance of the HbS gene from both parents results in homozygous sickle cell (SS) disease which is often a severe condition destroying red blood cells rapidly and blocking flow in blood vessels with painful and often serious complications2. The HbS mutation has occurred on at least three occasions in Africa, named after the areas where these were first described3, Benin, Senegal and Bantu (Central African Republic) and referred to as the beta globin haplotypes. A separate and fourth occurrence of the mutation was seen around the Arabian Gulf and India and designated the Arab-Indian or Asian haplotype4.

Significance of different haplotypes

Sickle cell disease in North and South America, the Caribbean and much of Europe occurs in people of African origin. This is mostly of the Benin haplotype and this form of the disease has been well documented, is relatively severe, and successful interventions have been developed to improve outcome of the disease. The disease of the Asian haplotype is generally milder because the mutation has occurred against a background of genetic features likely to inhibit sickling.

Sickle cell disease in patients of African origin

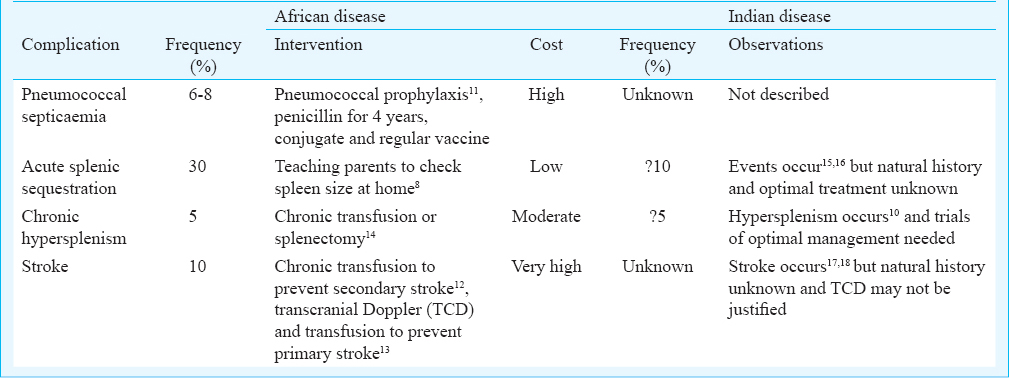

The spleen is central to much of the early pathology of African SS disease since the rapid development of intravascular sickling compromises splenic function in the first year of life5. Patients with African forms of SS disease often develop symptoms at 3-4 months and the greatest chance of dying is between 6-12 months of age6. Common causes of early death include pneumococcal sepsis7, acute splenic sequestration8, and stroke9. Hypersplenism10 occurs at later ages but contributes to both morbidity and occasionally mortality. Interventions which have successfully addressed some of these complications include pneumococcal prophylaxis11, teaching parents to detect acute splenic sequestration8, chronic transfusion to prevent secondary stroke12 and transcranial Doppler to detect the stenosis of cerebral vessels preceding stroke13 (Table).

Sickle cell gene in India

First described in the Nilgiri Hills of northern Tamil Nadu in 195219, the sickle cell gene is now known to be widespread among people of the Deccan plateau of central India with a smaller focus in the north of Kerala and Tamil Nadu20. Extensive studies performed by the Anthropological Survey of India21 have documented the distribution and frequency of the sickle cell trait which reaches levels as high as 35 per cent in some communities.

Sickle cell disease in India

Early studies22 described SS disease with higher levels of foetal haemoglobin, more frequent alpha thalassaemia, higher total haemoglobin and lower reticulocyte counts and persistence of splenomegaly compared to Jamaican SS disease. Several patients were first diagnosed by family study, some adults denying specific symptoms. These features were similar to the mild disease reported from the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia23 and were believed to characterize the Asian haplotype of SS disease. Persistence of splenomegaly and of presumed splenic function were important since the age-specificity of invasive pneumococcal disease falls sharply after the age of five years24 and if a functioning spleen persists beyond this age25, the risk of pneumococcal septicaemia may be markedly reduced. In contrast to this benign picture, studies from Central India report severe disease (defined as >3 bone pain crises, >3 transfusions/year) in 30 per cent children17 and supported by an analysis of 85 under five children hospitalized18. The latter study included 20 bacteraemic events due to Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacteria but no pneumococci. The pneumococcus is a fastidious organism, readily overgrown by other bacteria and possibly underestimated because of antibiotics preceding blood cultures; however, there is much information on nasopharyngeal carriage in India26 and since this usually precedes invasive disease, the apparent lack of pneumococcal septicaemia in Indian sickle cell disease may reflect persisting splenic function.

The coincidence of large tribal populations with the ‘sickle cell belt’ of Central India and northern Kerala and Tamil Nadu has given rise to the assumption that tribal people are more prone to the HbS gene although this seems widely distributed among tribal and non-tribal people27. Sometimes striking differences have been reported, a tribal population in Valsad having milder disease than a non-tribal population in Nagpur28 and attributed to extremely high frequencies of alpha thalassaemia in the tribal group. The apparent disparity in clinical severity between different reports in India reflects to some extent the mode of ascertainment of patients, studies of hospitalized cases1718 not surprisingly revealing severe disease compared with the studies in Burla22 which focused on outpatient attendance. Addressing the question of intrinsic severity of patients in Central India was the focus of a study recently completed in Akola Medical College, Maharastra, where 40 per cent of patients with sickle cell disease were found to have sickle cell-beta thalassaemia and of the 54 per cent with SS disease, alpha thalassaemia occurred in only 16 per cent29 compared with over 50 per cent observed in Odisha22 and 86 per cent in Valsad28.

Newborn screening

It is becoming clear that a great deal remains to be learnt about Indian sickle cell disease (Table) and the best way of achieving this is by studies based on newborn screening which removes the bias of symptomatic selection. Newborn screening is already underway in India303132 and the robust nature of dried blood samples means that this need not be confined to hospital deliveries but could be extended to domiciliary deliveries. Follow up from birth with regular assessments of haematology, clinical features, and growth would provide the knowledge base needed for development of locally appropriate models of care and would also provide populations for therapeutic trials. The data generated by such studies would allow definition of the role of hydroxyurea therapy, of blood transfusion, of bone pain crises, of stroke and priapism, the nature of infections, and the possible role of infection prophylaxis.

Future directions

Who would be responsible for these studies? Multicentre studies pioneered by the Indian Council of Medical Research have begun the process of systematic documentation of the disease171832. The National Rural Health Mission, created in 2005, is making major contributions with their programmes in south Gujarat but also at Burla Medical College, Sambalpur University in western Odisha33. The Gujarat Sickle Cell Anaemia Control Society was formed in 2011 to coordinate the many activities in Gujarat State. State sickle cell programmes, especially those in Gujarat32, Maharastra and Chhattisgarh3435 focus on extending population screening to detect the sickle cell trait with a view to offer genetic counselling and to identify patients with sickle cell disease for referral to clinics and follow up. Much resources and goodwill are directed towards the problem of sickle cell disease in India but studies of the clinical features and natural history are urgently required to generate locally appropriate models of care. Studies based on newborn screening should be a priority35 and without this information, Indian physicians may feel coerced to use models of care developed for patients of African origin36. This information will also be necessary to define the role of premarital screening and the need and acceptability of prenatal diagnosis in the prevention of disease. The increasing sophistication of laboratory and molecular services renders these technologies available to Indian patients but their role in Indian sickle cell disease is critically dependent upon a greater understanding of clinical severity and its determinants37. This knowledge is also essential for the development of appropriate genetic counselling3839.

Conclusions

Assuming that models of care developed for African disease should be followed in India may be inappropriate and waste limited resources. Studies based on newborn screening will avoid symptomatic selection and provide the best clinical data.

References

- Improved survival in homozygous sickle cell disease: lessons from a cohort study. Br Med J. 1995;311:160-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell disease (3rd ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Structural analysis of the 5’ flanking region of the beta-globin gene in African sickle cell anemia patients: further evidence for three origins of the sickle cell mutation in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4431-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical survey of ßs-globin gene haplotypes: Evidence for an independent Asian origin of the sickle-cell mutation. Am J Hum Genet. 1986;39:239-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute splenic sequestration in homozygous sickle cell disease: natural history and management. J Pediatr. 1985;107:201-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute splenic sequestration and hypersplenism in the first five years in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:765-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell anemia. A randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1593-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of recurrent stroke in patients with sickle cell disease treated with erythrocyte transfusions. J Pediatr. 1995;126:896-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:5-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postsplenectomy course in homozygous sickle cell disease? J Pediatr. 1999;134:304-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell disease in India. (Netaji Oration) J Assoc Physicians India. 1991;39:954-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity pattern in hospitalized under five children with sickle cell disease. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138:317-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two different forms of homozygous sickle cell disease occur in Saudi Arabia. Br J Haematol. 1991;79:93-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Splenic function in sickle-cell disease in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. J Pediatr. 1984;104:714-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pneumococcal disease in India: the dilemma continues. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140:165-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of á-thalassemia on sickle-cell anemia linked to the Arab-Indian haplotype in India. Am J Hematol. 1997;55:104-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell disease in central India: A potentially severe syndrome. Indian J Pediatr In press 2016

- [Google Scholar]

- Neonatal screening of sickle cell anemia: a preliminary report. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:747-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Newborn screening shows a high incidence of sickle cell anemia in Central India. Hemoglobin. 2012;36:316-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feasibility of a newborn screening and follow-up programme for sickle cell disease among South Gujarat (India) tribal populations. J Med Screen. 2015;22:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of deletional alpha thalassemia and sickle gene in a tribal dominated malaria endemic area of eastern India. ISRN Hematol 2014 March 11:745245.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population screening for the sickle cell gene in Chhattisgarh State, India: an approach to a major public health problem. J Community Genet. 2011;2:147-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Chhattisgarh state screening programme for the sickle cell gene: a cost-effective approach to a public health problem. J Community Genet. 2015;6:361-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive integrated care for patients with sickle cell disease in a remote aboriginal tribal population in Southern India. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:702-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sickle cell anemia - molecular diagnosis and prenatal counselling: SGPGI experience. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:68-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- A century after discovery of sickle cell disease: keeping hope alive. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:793-5.

- [Google Scholar]