Translate this page into:

Burkholderia cepacia complex nosocomial outbreaks in India: A scoping review

For correspondence: Dr Vikas Gautam, Department of Medical Microbiology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, 160 012, India e-mail: r_vg@yahoo.co.uk

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) is an opportunistic pathogen that causes severe infections in immunocompromised individuals. It is a common contaminant of medical drugs, solutions and devices used in healthcare setups. This scoping review aimed to assess Bcc outbreaks in Indian hospital settings and address a wide range of sources to improve outbreak management. As per PRISMA-ScR guidelines, electronic databases ‘Embase’, ‘PubMed’ and ‘Web of Science’ were searched from 1993 to September 2024 to identify studies reporting Burkholderia cepacia complex outbreaks across India. The search identified 22 outbreak reports meeting the inclusion criteria. Bacteremia was the most common presentation in twenty studies, followed by acute-onset post-operative endophthalmitis in two studies. In 14 outbreak studies, B. cepacia was the identified species, whereas five studies had Bcc; one study each had B. cenocepacia, B. multivorans and B. contaminans isolated. Most outbreaks were associated with contaminated pharmaceuticals (45.4%) and medical (18.1%) products in contrast to the environment as a source (13.6%). Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was employed to study clonality among isolates in six outbreaks. This review highlights that varied medical products and environmental surfaces/objects can harbour Bcc and act as potential sources of Bcc outbreaks in hospitals. Ensuring immediate identification of Bcc from clinical samples, regular sterility checks, thorough epidemiological investigations, and timely infection control and prevention measures are critical to help manage and prevent these outbreaks and the subsequent mortality.

Keywords

Burkholderia cepacia complex

contaminated pharmaceutical products

India

MLST

molecular typing

outbreak

Members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) consisting of 22 species are oxidase-positive, rod-shaped, non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria (NFGNB)1,2. They are found ubiquitously in various natural and man-made habitats owing to their exceptional metabolic adaptability3. These opportunistic pathogens are responsible for a wide range of infections and complications in immunocompromised individuals4,5. Their ability to cause life-threatening infections in intensive care settings and paediatric patients is well recognized.

Bcc causes severe pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) patients6,7. Additionally, it induces bacteremia in patients, with host and environmental risk factors like prolonged hospital stay, medical co-morbidities, use of central venous catheters (CVC) and exposure to medical products, like ultrasound gels and devices8,9.The bacteria’s survival and replication in indwelling invasive devices, resistance to disinfectants, and ability to persist in moist environments and surfaces like water tanks, sinks, taps and others with restricted nutrition highlight its significance as an emerging nosocomial pathogen globally. Bcc’s endurance to pharmaceutical products and devices makes them function as a potential reservoir of infection in hospital settings, facilitating outbreaks in the event of breaches in infection prevention and control practices (IPC)3,5,10. The patient-to-patient transmission also contributes to Bcc colonization. Bcc exhibits a distinctive antimicrobial profile, posing challenges to treatment. Intrinsic resistance, especially to antibiotics like polymyxins and aminoglycosides, and rising multi-drug resistance further complicates management2,11. Moreover, a limited understanding of pathogenicity, laboratory identification and differentiation from other NFGNBs leads to underreporting and inadequate treatment of Bcc infections.

Numerous Bcc outbreaks from hospital settings have been reported globally, including those from India. Bcc has been known to contaminate many medical products, such as ultrasound gel12, detergents, and moisturizing creams13, pharmaceutical preparations like IV fluids14, chlorhexidine solutions and mouthwash15, rubber stoppers of drug vials16, nebulized salbutamol17 and devices like respiratory equipment17. It is known to survive in distilled water by utilizing trace amounts of organic compounds and carbon dioxide as energy sources18,19. Intravenous (IV) medications, including antiemetic drug vials and multidose amikacin vials, have been identified as sources of infection. These outbreaks have been reported in ICU settings and dialysis units and are common among paediatric populations16,20. However, in the available literature, a comprehensive study analyzing the Bcc outbreaks, specifically of Indian origin, is lacking. To address this gap and create awareness, we conducted a scoping review on nosocomial Bcc outbreaks from India that were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The objective of the review was to analyse infection sources, outbreak investigations, affected patient populations, and control strategies in the Indian context.

Materials & Methods

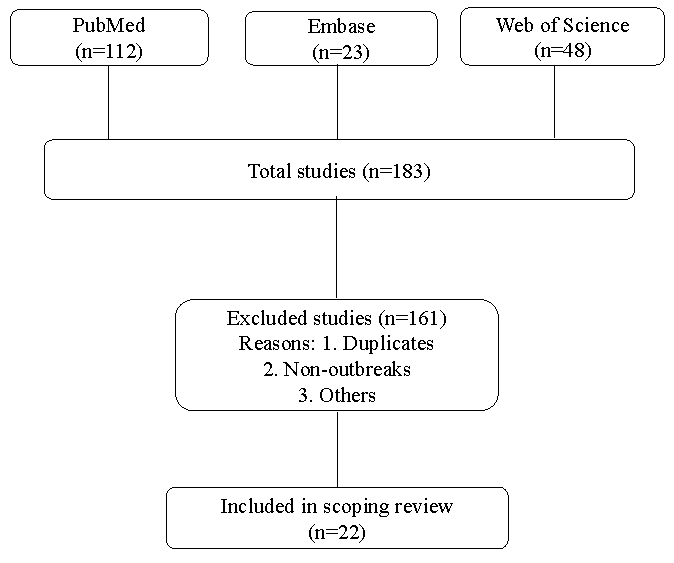

The study followed PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines. The PRISMA-ScR 22 points checklist (Supplementary Table) has been referred to while formulating this review. Databases such as ‘PubMed’ (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), ‘Embase’ (https://www.embase.com) and ‘Web of Science’ (https://clarivate.com) were utilized. Literature published between 1993 and September 2024 and only in English was included in this review. Furthermore, the references cited in the included studies were assessed (Figure). The combination of search terms used was as follows: (Burkholderia cepacia complex OR Burkholderia species OR Pseudomonas cepacia; MeSH Terms) AND (outbreak; MeSH Terms) AND (India; MeSH Terms) (Supplementary Material). Search terms like contaminated drugs or pharmaceuticals were not used as they would limit the search results.

- Flowchart outlining the review process for including the studies.

Included were prospective, retrospective and cohort studies assessing Bcc outbreaks due to any source in Indian hospital settings. However, conference abstracts and case reports (less than 3 patients infected) were excluded. Studies that only reported the outbreak up to the point of identification, without investigating potential sources, were also excluded. This was based on the rationale that without investigating the possible source, no valid conclusions can be drawn; neither would it substantially contribute to infection prevention strategies for avoiding such nosocomial outbreaks. We thoroughly documented essential details, encompassing outbreak features, patient population, nature of infections, investigation for infection source, and the implementation of infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies to manage the outbreak. ‘Extrinsic contamination’ of medical products is defined as the introduction of contamination during product utilization, while ‘intrinsic contamination’ refers to contamination occurring before use, specifically at the level of manufacturing21.

Three reviewers (AS, SM, and LS) charted the data to extract data from the included studies. The table was created in two parts. First, the general characteristics of the published studies were charted with the following information: author, year of outbreak, city/State of India, number of patients affected, patient population, source of outbreak, type of Burkholderia species identified, infection type, and what method of molecular typing, if used, was done. The charted data was then rearranged according to a common denominator: the outbreak’s source. Source categories were pharmaceutical preparations, medical products, environment, medical devices, and no source identified. The second table compiled the data of studies that successfully identified the source of the outbreak, and the relevant infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies used to curb the outbreaks. The assessment of potential bias and heterogeneity was not conducted. Basic statistical methods like percentages were used to summarize and communicate key trends in the data.

Results

For this analysis, our search identified 22 published studies of hospital-acquired Burkholderia cepacia complex outbreaks across India, which met our criteria (Table I)12,15,16,19,20,22-38. Ten outbreaks were reported from southern States of India12,19,22,23-29 (6 from Tamil Nadu, 2 from Karnataka, 1 from Puducherry, & 1 from Kerala), six outbreaks were reported from western States15,16,20,30-32 (5 from Maharashtra & 1 from Rajasthan), five from northern States33-37 (2 from Delhi, 1 each from Haryana, Chandigarh and Jammu & Kashmir) and one from the eastern State of West Bengal38.

| S. No. | Author | Year of the Outbreak | State of India | No. & patient population affected | Source | Burkholderia species isolated | Infection type | Molecular confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Pharmaceutical preparations (10) | ||||||||

| 1. | Singhal et al20 | 2009 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | 13 Adults, Chemotherapy day care unit | Antiemetic granisetrone IV medication | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 2. | Tandel et al15 | 2010 | Pune, Maharashtra | 12, Surgical ICU | Cetrimide + Chlorhexidine solution for skin antisepsis | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 3. | Lalitha et al22 | December 2011-February 2012 | Madurai, Tamil Nadu | 13, post-cataract surgery patients | Topical anaesthetic eye drops | Burkholderia cepacia | Endophthalmitis | BOX-PCR |

| 4. | Mali et al16 | June 2012-January 2013 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | 76, Paediatric ICU & Paediatric ward | Rubber stopper of amikacin vials | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Bacteremia | recA PCR & E-MLST |

| 5. | Paul et al19 | January 2014 | Mangalore, Karnataka | 12, NICU | Opened IV fluid 5% Dextrose, Normal saline & CPPV humidifier water (Also included in Environment category) | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 6. | Shrivastava et al31 | October 2015 | Mumbai, Maharashtra | 7, NICU | Unopened & opened vials of caffeine citrate | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 7. | Fomda et al35 | October 2017 -October 2018 | Srinagar, Jammu & Kashmir | 121, Surgical ICU | Unopened Normal saline, Chlorhexidine mouthwash | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 8. | Sridharan et al23 | February-March 2019 | Chennai, Tamil Nadu | 40, Cardiac care unit | Unopened vials of Diltiazem | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 9. | Murugesan et al24 | March 2019 | Vellore, Tamil Nadu | 11, Cardiology ward | Opened & unopened vials of Diltiazem | Burkholderia contaminans | Bacteremia | MLST |

| 10. | Ghafur et al25 | August- December 2021 | Chennai, Tamil Nadu | 56, Oncology ward | Antiemetic palonosetron IV medication | Burkholderia cenocepacia | Bacteremia | MLST |

| Source: Environment (2+1) | ||||||||

| 11. | Rastogi et al33 | April-November 2014 | New Delhi | 48, Neurotrauma ICU | Water supply & RO water | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia, CLABSI, VAP | MLST |

| 12. | Antony et al26 | 2016 | Mangalore, Karnataka | 3, Paediatric ICU | Distilled water used for nebulizers & humidification of oxygen | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| Source: Medical products (4) | ||||||||

| 13. | Solaimalai et al12 | October 2016 | Vellore, Tamil Nadu | 7, Paediatric ICU | In-use Ultrasound gel | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Bacteremia | MLST |

| 14. | Yamunadevi et al27 | November 2016-January 2017 | Chennai, Tamil Nadu | 24, Cardiac care unit | Ultrasound gel | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 15. | Dogra et al37 | February 2020 | Chandigarh | 4, Paediatric surgical ward | In-use Ultrasound gel | Burkholderia multivorans | Bacteremia | MALDI-TOF, MLST |

| 16. | Raj et al28 | June 2018- December 2020 | Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala | 84, inborn nursery | In-use Ultrasound gel | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| Source: Medical device (1) | ||||||||

| 17. | Bharara et al36 | March 2019 | Gurgaon, Haryana | 4, NICU | Suction apparatus | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| Source: Not identified (5) | ||||||||

| 18. | Bhise et al30 | April 2013 | Nagpur, Maharashtra | 10, NICU | No source identified | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 19. | Bhatia et al34 | August 2015-July 2016 | New Delhi | 147, Various ICU’s | No source identified | Burkholderia cepacia | Bacteremia | Not performed |

| 20. | Gupta et al32 | September-October 2016 | Jaipur, Rajasthan | 14, Oncology ward | No source identified | Burkholderia cepacia | CLABSI | Not performed |

| 21. | Baul et al38 | September 2016 – February 2017 | Kolkata, West Bengal | 29, Haemato-oncology ward | No source identified | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Bacteremia | PCR & PFGE |

| 22. | Deb et al29 | July-August 2019 | Puducherry | 5, (4 post-cataract & 1 post-keratoplasty) | No source identified | Burkholderia cepacia complex | Endophthalmitis | Not performed |

CLABSI, central line associated bloodstream infection; CPPV, continuous positive pressure ventilation; E-MLST, extended multi-locus sequence typing; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight; MLST, multi-locus sequence typing; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PFGE, pulse field gel electrophoresis; RO, reverse osmosis; VAP, ventilator associated pneumonia

Sources of Bcc outbreaks in India

Out of the 22 Bcc outbreak studies, a source could be identified in 17 studies while in five studies29,30,32,34,38, no source was identified. The majority of the outbreak investigations (n=10) were concerned with pharmaceutical products, which included IV antiemetics granisetron20 and palonosetron25, topical anaesthetic eyedrops22, upper surface of rubber stopper of sealed multidose amikacin vials16, opened IV fluids19,35 (5% Dextrose, normal saline), unopened and opened vials of caffeine citrate31, diltiazem vials23,24, cetrimide and chlorhexidine solution for skin antisepsis15 and chlorhexidine mouthwash35. The source was identified to be distilled water used for nebulization and oxygen humidification in two studies19,26. The gel used during Ultrasonography (USG) was recognized as the source of the Bcc outbreak in four studies12,27,28,37. One study each was associated with contaminated water supply, including RO (reverse osmosis) water33 and suction apparatus36.

Among the identified sources of the outbreaks, the source was associated with pharmaceutical preparations in 45.4 per cent of the studies, the environment 13.6 per cent, medical products in 18.1 per cent, and devices in 4.5 per cent. Out of the 14 studies implicating medical and pharmaceutical products as culprits, intrinsic contamination was present in 10 compared to four outbreaks having extrinsic contamination.

General characteristics of the Indian Bcc outbreaks

Seven hundred and forty patients were affected across these 22 outbreaks. With pharmaceutical preparations as the source of the outbreak, the majority occurred in intensive care unit (ICU) settings as reported in five studies15,19,23,31,35 involving 192 patients. Hospital wards were affected in three studies with a total of 80 patients, including chemotherapy day care unit20, cardiology ward24, and oncology ward25. One study reported a Bcc outbreak among 13 post-cataract surgery patients associated with anaesthetic eyedrops22. Another study reported an outbreak associated with contaminated rubber stoppers of amikacin vials, involving both paediatric ICU and ward16, affecting 76 children. The majority of the patients were adults (n=266), where as paediatric population associated with pharmaceutical preparation-related outbreaks comprised 95 individuals. Among these 19 (20%) were exclusively confined to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Out of the 10 studies, three mentioned outcomes in terms of mortality, which were nil (0/13) in Singhal et al20, 27.6 per cent (21/76) in Mali et al16, and 16.6 per cent (2/12) in Paul et al19. In one study by Lalitha et al22 involving cataract surgery patients, 69 per cent (9/13) had a final visual acuity of 6/60 or better, 23 per cent (3/13) had a vision of perception of light and 7.6 per cent (1/13) had a final vision of 1/60.

Three outbreaks linked to environmental contamination occurred in neurotrauma33, neonatal19, and paediatric26 ICUs, involving 63 patients. Of these, 48 were adults, and 15 were in paediatric age group. Two out of three studies mentioned outcomes in terms of mortality, nil (0/3) in Antony et al26, and 16.6 per cent (2/12) in Paul et al19. Bcc outbreaks linked to medical products, specifically ultrasound gel, were reported in four studies. Two of these outbreaks involved ICU patients12,27, while one occurred in a paediatric ward37 and another in an inborn nursery28. Twenty-four adults were affected, whereas 95 were paediatric patients, of which 84 (88.4%) were neonates. Two studies out of four mentioned outcomes as 42.8 per cent (3/7) mortality by Solaimalai et al12, and a case fatality rate of 26 per cent by Raj et al28. One study pinpointed suction apparatus36 (medical device) as the source, involving four patients in the neonatal ICU, and the mortality rate was 25 per cent (1/4).

Outbreaks in which sources could not be identified, the majority occurred in ICU settings, as reported in two studies30,34, involving a total of 157 patients. Oncology32 and hemato-oncology38 wards were affected in two studies with 43 patients. One outbreak was reported among five post-operative patients following cataract and keratoplasty surgery29. Outbreaks with no source identified affected 195 adults and ten neonates. Mortality outcomes were reported in two studies: Bhise et al30 documented a rate of 30 per cent (3/10), while Baul et al38 reported 3.5 per cent (1/28). One study by Gupta et al32 reported the removal of central venous catheters as an outcome, with a rate of 71.4 per cent (10/14). In a study by Deb et al29 involving five patients with endophthalmitis, the outcomes recorded were as follows: two patients achieved a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/60, two had a BCVA better than 20/200, and one patient had no perception of light.

In 20 studies, patients presented with Bcc bacteremia12,15,16,19,20,23-28,30-38. Out of these, two studies had central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI)32,33, and one study also reported ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP)33. In the remaining two outbreak studies, endophthalmitis was the clinical presentation22,29. Only four studies specified the exact antibiotic treatment administered, while the rest stated that susceptibility patterns guided treatment without specifying the drugs. Ceftazidime in combination with meropenem/levofloxacin12, and cotrimoxazole in combination with meropenem/ceftazidime28 were used for treatment in one study each.

The species identified in 14 outbreaks was Burkholderia cepacia15,19,20,22,23,26-28,30,31-35. In five studies, Burkholderia cepacia complex12,16,29,36,38 was identified, and B. cenocepacia25, B. multivorans37 and B. contaminans24 was identified as the causative agent in three independent outbreaks. Bcc identification was performed using conventional phenotypic methods in seven studies12,15,20,22,27,30,32. Seven studies employed the automated Vitek 2 system19,25,26,28,31,34,36, and five studies used Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF)23,24,29,35,37. Additionally, recA PCR was used in two studies16,33, and one study utilized the automated MicroScan panel for identification38.

Molecular methods used for clonal association

Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) was predominantly used to assess clonality in isolates for six outbreaks12,16,24,25,33,37. Other techniques, such as repetitive extragenic palindromic-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (BOX-PCR)22, pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)38 in one outbreak each, and MALDI-TOF37 in another, were utilized to study clonal association. In 14 of the documented outbreaks, microbial typing was not conducted.

Management of Indian Bcc outbreaks

Various IPC strategies were used to curb the outbreaks (Table II). In most studies, contaminated stocks of pharmaceutical products were discarded. The concerned manufacturers were informed, and regular sterility testing was implemented15,16,19,20,22-24,35. The process of medication preparation and administration was strictly regulated16,20,33,35. Single-use IV fluids and replacement of multidose injection vials with single-use ampules were mandated16,19,35. Contaminated chlorhexidine was replaced with alcohol-based skin antiseptics15.Ventilator circuit cleaning was enforced19.

| S. No. | Author | Source of the outbreak | Patient population | IPC Strategies to control outbreak |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Singhal et al20 | Antiemetic granisetron IV medication (Intrinsic) | Chemotherapy day care unit |

Assessment of compliance with all infection control protocols Medication preparation & administration was regulated Use of only collapsible/closed intravenous fluid bags initiated Insertion process of ports was reviewed Day care unit was fogged & disinfected Results communicated to manufacturer; medication brand withdrawn |

| 2. | Tandel et al15 | Cetrimide + chlorhexidine solution for skin antisepsis (Intrinsic) | Surgical ICU |

Contaminated stocks discarded Alternative use of alcohol-based antiseptics |

| 3. | Lalitha et al22 | Topical anaesthetic eye drops (Intrinsic) | Post-cataract surgery patients |

Discontinuation of eye drops Notification of outbreak through All India Ophthalmology Association Long-term follow up of patients |

| 4. | Mali et al16 | Rubber stopper of multidose amikacin vials (Intrinsic) | Paediatric ICU & Paediatric ward |

Documentation & communication of outbreak to paediatricians, medical store & administrative staff Batch of multidose amikacin injection vials discarded Replacement of multidose vials with ampoules Conforming to safe injection practices Enforcing strict adherence to hand hygiene |

| 5. | Shrivastava et al31 | Opened & unopened Vials of anti-apnoea drug caffeine citrate (Intrinsic) | NICU | Not mentioned |

| 6. | Fomda et al35 | Unopened Normal saline, Chlorhexidine mouthwash, outer rim of sinks water faucet (intrinsic & extrinsic) | Surgical ICU |

Assessment done by IPCAT-H Onsite training in IPC & HAI surveillance 4 infection control nurses and 2 dedicated doctors hired to oversee IPC activities Medication & IV fluid administration was regulated Hand hygiene reinforced Single dose saline vials mandated Compliance to central line bundle care was assessed, use of femoral CVC’s stopped Chlorhexidine mouthwash was discarded Water tank treated with high strength calcium hypochlorite |

| 7. | Sridharan et al23 | Unopened vials of Diltiazem (intrinsic) | Cardiac care unit |

Alcohol hand rub installed at various places Diltiazem stock vials returned; drug company informed Policy to procure quality control check certificate for batches of all IV drugs |

| 8. | Murugasen et al24 | Opened & unopened vials of Diltiazem (Intrinsic) | Cardiology ward |

Stock of Diltiazem vials discarded; results were communicated to manufacturer Hand hygiene reinforced Terminal cleaning advised As a part of quality assurance, sterility testing of all pharmaceutical products at regular intervals implemented |

| 9. | Ghafur et al25 | Antiemetic palonosetron IV medication (Intrinsic) | Oncology ward |

Results communicated to Drug Controller General of India and manufacturer; medication brand withdrawn IPC strategies strengthened Tracked patients who received medication Central line and medication ports removed from patients with positive culture |

| 10. | Paul et al19 | Opened IV fluid 5% Dextrose, Normal saline & CPPV humidifier water (Extrinsic) | NICU |

Discarding stocks of IV fluids Replacement with single use IV fluids Enforcing intravenous line care & ventilator circuit cleaning |

| 11. | Rastogi et al33 | Water supply & RO water | Neurotrauma ICU |

Infected patients cohorted by physical barriers into cubicles Cubicles fogged with hydrogen peroxide vapour Terminal cleaning of cubicles, bed rails & surroundings with quaternary ammonium compounds Hand hygiene reinforced Medication & IV fluid administration was regulated Cleaning and chlorination of water tanks Compliance to central line bundle care was assessed |

| 12. | Antony et al26 | Distilled water used for nebulizers & humidification of oxygen (Extrinsic) | Paediatric ICU |

Fumigation Hand hygiene reinforced Screening ICU staff Cohorting infected patients Shelf life of distilled water stored in large containers restricted to 24 hours |

| 13. | Solaimalai et al12 | Ultrasound gel containers (Extrinsic) | Paediatric ICU |

Cohorting infected children Hand hygiene reinforced followed by audit to check compliance Environmental disinfection Use of ultrasound probe cover was implemented |

| 14. | Yamunadevi et al27 | Ultrasound gel containers (Intrinsic) | ICU |

Chlorhexidine used to wipe ultrasound gel Use of ultrasound probe cover was implemented Probe cleaned with alcohol spray between each patient |

| 15. | Dogra et al37 | In-use Ultrasound gel (Extrinsic) | Paediatric surgical ward | Not mentioned |

| 16. | Raj et al28 | In-use Ultrasound gel (Extrinsic) | Inborn-nursery |

Withdrawal of contaminated multi-use USG gel Introducing practice of sterile single-use USG gel |

| 17. | Bharara et al36 | Suction apparatus (Extrinsic) | NICU |

Cohorting of cases Suction bottles were cleaned with 2% glutaraldehyde solution Hand hygiene & IPC practices were reinforced |

CPPV, continuous positive pressure ventilation; HAI, hospital acquired infection; IPCAT-H, infection prevention and control assessment tool for health care facilities; IPC, infection prevention and control practices; USG, ultrasonography

Distilled water stored in the ICU meant for nebulization, humidification of oxygen and flushing feeding tubes was limited to a shelf-life of 24 hours26.Two outbreaks resulting from contaminated water sources were addressed through the application of chlorine, and calcium hypochlorite, respectively33,35.

Sterile covers were employed on ultrasound probes as a preventive measure to mitigate direct contact between the gel and patient’s skin12,27. The ultrasound probe disinfection using an alcohol spray after each patient encounter was mandated27. Suction bottles in the neonatal ICU were cleaned with 2% glutaraldehyde solution36.

IPC practices were assessed using the World Health Organization’s IPC programmes in healthcare facilities (IPCAT-H)35. The education and training of the staff in IPC and hospital acquired infection (HAI) surveillance was done on-site. Compliance with central line bundle care was assessed19,33,35. Use of femoral CVC’s was discouraged35. Infected patients were managed as appropriate and hand hygiene audits were conducted12,16,24,26,33,35,36.

Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive description of Bcc outbreaks in Indian hospital settings for the first time, encompassing all possible sources. This review highlights that these outbreaks majorly affect ICUs (57.1%). Patients in medical, surgical and trauma ICUs and those in paediatric wards and NICUs typically have lengthy hospital stay. They are subjected to various interventions, and their reliance on invasive medical devices and many broad-spectrum antibiotics makes them prone to bloodstream infections among others39. Outbreaks affecting ICUs were associated with different sources, including chlorhexidine solutions, amikacin and diltiazem vials, dextrose and normal saline solutions, ultrasound gels, and suction apparatus. Bacteremia was noted to be the most common presentation, possibly stemming from a breach in the skin via in-situ central lines and catheters, contaminated IV medication and solutions, ultrasound gels used for routine scanning, and open wounds, among other routes. Burkholderia cepacia was observed to be the predominant species among the isolates, as conventional methods of bacterial culture and biochemical reactions for identification limit many laboratories in India. Other less commonly isolated species were observed to be B. multivorans, B. contaminans and B. cenocepacia.

Identifying the outbreak source is crucial for implementing effective infection control measures. We observed that investigators in one-fourth of the outbreaks could not identify the source. This may be due to challenges in identifying the bacterium, not having access to a special Bcc isolation medium or insufficient knowledge about potential reservoirs of Bcc, resulting in inadequate sampling during surveillance. However, we could determine that about 45.4 per cent of the reported studies were associated with pharmaceutical preparations (including sterile intravenous medications, solutions and disinfectants). Incriminated products were contaminated IV antiemetics granisetron and palonosetron, topical anaesthetic eyedrops, rubber stopper of multidose amikacin vials, IV fluids like 5% dextrose, normal saline, caffeine citrate vials, diltiazem vials, cetrimide and chlorhexidine solution and chlorhexidine mouthwash. We noted two outbreaks among cataract and keratoplasty surgery patients presenting with acute-onset postoperative endophthalmitis. A variety of perioperative and intraoperative sterile products used during eye surgeries are known to cause cluster endophthalmitis, such as intraocular lens solution, balanced salt solution, and others40. Topical anaesthetic eye drops were identified as the source of one of these outbreaks. The ability of Bcc to utilise a wide variety of organic compounds as carbon and energy source is a testament to the fact that it grows and thrives in sterile drug solutions, which are difficult to catabolize. Members of Bcc can oxidise aromatic and nitroaromatic compounds present in drugs, with the help of monooxygenase and dioxygenase enzymes. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, Bcc is believed to spread through water, raw materials and equipment surfaces, resulting in contamination of nonsterile products like mouthwashes, nasal saline solutions etc.,10 as was seen in a Bcc outbreak by Bilgin et al41 associated with contaminated chlorhexidine mouthwash. Once they contaminate the biocide, the most worrisome property of Bcc bacteria is their ability to grow and proliferate in these compounds. Resistance to disinfectants and antiseptics can be intrinsic or acquired. Various mechanisms include the presence of a highly charged lipopolysaccharide layer acting as a barrier; efflux pumps, notably of the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) transporter family acting against biocides like benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine gluconate42,43, biofilm formation, and mutations in genes encoding cell wall, outer membrane proteins and porins. Bcc has been shown to contaminate analgesic gels and intravenous fentanyl in other reported outbreaks44,45. The presence of Bcc in drugs and solutions degrades the active compound and also contributes to the formation of toxic metabolites, potentially transmitting infection to vulnerable populations10.

Contamination is often linked to breaches in IPC measures rather than intrinsic drug contamination, leading to delays in control efforts. This review shows that medical products like ultrasound gel should also be considered as possible source of infection during Bcc outbreak, as was seen in 18.1 per cent of the reported studies. USG scanning is routinely performed in intensive care, trauma and surgical units. Bcc species can degrade the stabilizing agent of ultrasound gels, that is, parabens (p-hydroxybenzoic acid esters), and hence contaminate the gel46. Intrinsic contamination of ultrasound gel has been reported when recovered from unopened vials27. We observed environmental contamination of water supply and distilled water as source of infection in 13.6 per cent of the included studies. The adaptive properties of Bcc hypothesized to facilitate growth in water include tolerance to limited nutrition, interaction with other bacteria, morphological switch to coccobacilli and temperature variations18,42.

Among the studies where molecular testing was done, MLST was the most common (6/8, 75%) employed method for Bcc typing12,16,24,25,33,37. One study each utilised PFGE38, BOX-PCR and MALDI-TOF as typing methods22,37. However, 14 studies did not conduct molecular analysis. They concluded their findings based on the phenotypic properties of isolating Bcc bacteria with similar antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, pinpointing a single common source and cessation of the outbreak after removing the source. MLST offers high resolution in distinguishing closely related strains, whereas PFGE is time-consuming and less sensitive in delineating within species. MLST’s digital sequence data aids computational analysis and data storage, contrasting with the visual banding pattern observed in PFGE, making it more subjective to interpretation47,48. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) has appeared to demonstrate superior discriminatory power in the recent past. WGS has a high cost and is time-consuming, restricting its availability49. MALDI-TOF emerges as a promising new technique with a high level of differentiation among species. Studies have shown good accuracy of MALDI-TOF in correctly identifying Burkholderia species and correlating well with molecular methods like PCR, proving a sensitive and rapid alternative50,51.

Our review noted that most outbreaks where molecular typing was done were linked to a single sequence type. MLST identified a novel ST 824 in clinical and contaminated amikacin vial Bcc isolates16, establishing an epidemiological link and confirming the outbreak source, marking the first such study in the country. Surprisingly, two reported outbreaks33,37 involved the isolation of more than one Bcc species, possibly attributed to contamination with multiple Burkholderia species at the source. The average mortality rate documented for nine included studies was 18 per cent, exceeding the 10 per cent mortality rate noted by Hafliger et al52. However, many patients affected by Burkholderia cepacia complex infections in these outbreaks were in the ICU. They had multiple comorbidities, making it difficult to attribute mortality solely to the Bcc infection.

Commonly implemented IPC measures were observed, including product withdrawal, manufacturer communication, and regular sterility testing. Some studies also mentioned patient cohorting and hand hygiene regulation33. Specific measures included using single-use IV fluids, replacing multidose injection vials with ampules, substituting chlorhexidine with alcohol-based solutions, treating water tanks with chlorine, and employing sterile covers for ultrasound probes. We observed that outbreaks were more frequently associated with product contamination than medical devices (4.5%) or environment (13.6%). Similar findings were reported by Hafliger et al52 where the environment (8.1%) and devices (17.1%) were far less commonly associated with Bcc outbreaks than contaminated products. Current hospital guidelines inadequately address the proper use of medical and pharmaceutical products, contributing to bacterial growth through factors such as using outdated products, storing for prolonged periods after use, improper storage conditions, and utilizing small dispensable bottles for mass-procured items like alcohol-based antiseptics and USG gels10,53.

There are a few limitations in our scoping review. First, we focused exclusively on Indian studies. While this narrowed the evidence we could include, it allowed us to examine the role of contaminated pharmaceutical products and related manufacturing practices specific to India. Second, due to the paucity of limited published literature from India, we included case series involving 3-4 patients each and expanded our evidence beyond ICU outbreaks to include wards and daycare units. This review could not fully assess the overall heterogeneity of the included evidence. Third, we included some studies that did not provide detailed information on the infection prevention and control (IPC) measures implemented to contain the outbreak. Fourth, studies where the source of the outbreak could not be pinpointed but were investigated were also included.

Bcc, identified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as the predominant contaminant in water-based pharmaceuticals, prompts guidance for manufacturers, alerting them of the risk and emphasizing screening before final release of product from the manufacturing unit54,55. A similar approach incorporated in good manufacturing practices (GMP) could help other countries as well.

Overall, this review highlights the importance of recognizing Burkholderia cepacia complex as an emerging group of bacteria responsible for serious life-threatening hospital-acquired infections leading to outbreaks in the healthcare settings. Identifying the infection source poses challenges due to Bcc’s presence in diverse environments. However, thorough sampling, awareness of its pathogenicity and use of molecular typing methods can aid in this process. Implementing appropriate control measures post-source identification is crucial for outbreak containment.

Financial support & sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Genome-based classification of Burkholderia cepacia complex provides new insight into its taxonomic status. Biol Direct. 2020;15:6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Genomic features, antimicrobial susceptibility, and epidemiological insights into Burkholderia cenocepacia clonal complex 31 isolates from bloodstream infections in India. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1151594.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia complex: Emerging multihost pathogens equipped with a wide range of virulence factors and determinants. Int J Microbiol. 2011;2011:607575.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:144-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia complex: Beyond pseudomonas and acinetobacter. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:4-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcome of Burkholderia cepacia complex infection in cystic fibrosis adults. J Cyst Fibros. 2004;3:93-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review of a 7-year record of the bacteriological profile of airway secretions of children with cystic fibrosis in North India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37:203-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bloodstream infections traced to the use of Ringer lactate solution as multiple-dose vial for catheter flushing, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:832-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of Burkholderia cepacia complex in septicaemic patients in a tertiary care hospital, India. Nepal Med Coll J. 2009;11:222-4.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria: A feared contamination risk in water-based pharmaceutical products. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33:e00139-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Burkholderia cepacia complex & stenotrophomonas maltophilia from North India: Trend over a decade (2007-2016) Indian J Med Res. 2020;152:656-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound gel as a source of hospital outbreaks: Indian experience and literature review. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2019;37:263-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisturizing body milk as a reservoir of Burkholderia cepacia: Outbreak of nosocomial infection in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2008;12:R10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The various lifestyles of the Burkholderia cepacia complex species: A tribute to adaptation. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia pseudobacteremia traced to contaminated antiseptic used for skin antisepsis prior to blood collection. Rev Res Med Microbiol. 2016;27:136-40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia complex in the paediatric unit of a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2017;35:216-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteremia in immunocompetent children caused by contaminated nebulized sulbutamol in Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:394-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in distilled water for 16 years. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:598-600.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteremia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Indian J Pediatr. 2016;83:285-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteremia in a chemotherapy day care unit due to intrinsic contamination of an antiemetic drug. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:117-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic contamination – the associated infective syndromes. In: Phillips I, Meers PD, D’Arcy PF, eds. Microbiological Hazards of Infusion Therapy. Dordrecht: Springer; 1976. p. :145-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postoperative endophthalmitis due to Burkholderia cepacia complex from contaminated anaesthetic eye drops. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1498-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of B. cepacia bacteremia following use of contaminated drug vials in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2022;40:119-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic methods and identification challenges experienced in a Burkholderia contaminans outbreak occurred in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2021;39:192-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diving deep for the needle in the haystack: An outbreak investigation of Burkholderia cenocepacia bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2024;45:677-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A sporadic outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteremia in pediatric intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in coastal Karnataka, South India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2016;59:197-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bacteraemia in a tertiary care centre due to contaminated ultrasound probe gel. J Hosp Infect. 2018;100:e257-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound gel as a source of Burkholderia cepacia sepsis outbreak in preterm neonates. J Neonatol. 2025;39:37-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical profile, visual outcome and root cause analysis of post-operative cluster endophthalmitis due to Burkholderia cepacia complex. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:164-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia an emerging cause of septicemia-an outbreak in a neonatl intensive care unit from a tertiary care hospital of central India. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2013;10:41-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- An unusual source of Burkholderia cepacia outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2016;94:358-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia catheter-related bloodstream infection in cancer patients with long-term central venous devices at a tertiary cancer centre in India. Indian Anaesth Forum. 2018;19:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological investigation and successful management of a Burkholderia cepacia outbreak in a neurotrauma intensive care unit. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;79:4-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pseudo-outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia blood stream infections in intensive care units of a super-speciality hospital: A cross-sectional study. Int J Med Sci Public Heal. 2017;6:1139-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia bloodstream infections in a tertiary-care facility in northern India detected by a healthcare-associated infection surveillance network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44:467-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteremia outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit: A case series. J Med Case Rep. 2020;14:76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia multivorans sepsis outbreak in a neonatal surgical unit of a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88:725.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia infection: a systematic study in a hematology-oncology unit of a tertiary care hospital from Eastern India. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2018;10:e2018051.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteremia among intensive care unit patients without cystic fibrosis: A case-control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:951-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak of acute post-cataract surgery Pseudomonas sp. endophthalmitis caused by contaminated hydrophilic intraocular lens solution. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:564-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An outbreak investigation of Burkholderia cepacia infections related with contaminated chlorhexidine mouthwash solution in a tertiary care center in Turkey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:143.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic resistance of Burkholderia cepacia complex to benzalkonium chloride. mBio. 2016;7:e01716-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the interplay of resistance nodulation division efflux pumps, Amp C and Opr D in antimicrobial resistance of Burkholderia cepacia complex in clinical isolates. Microb Drug Resist. 2020;26:1144-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of an outbreak of Burkholderia cepacia infection caused by drug contamination in a tertiary hospital in China. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:199-203.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of bacteremia due to Burkholderia contaminans linked to intravenous fentanyl from an institutional compounding pharmacy. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:606-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkholderia cepacia infections associated with intrinsically contaminated ultrasound gel: The role of microbial degradation of parabens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:291-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multilocus sequence analysis reveals high genetic diversity in clinical isolates of Burkholderia cepacia complex from India. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35769.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Accurate identification of members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex in cystic fibrosis sputum. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2016;62:221-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDI-TOF MS meets WGS in a VRE outbreak investigation. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:495-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex species recovered from cystic fibrosis patients using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;92:145-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: An emerging tool for unequivocal identification of non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:665-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of healthcare-associated Burkholderia cepacia complex outbreaks: Presentation, causes and outbreak control. Infect Prev Pract. 2020;2:100082.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of ultrasound gel associated Burkholderia cepacia complex outbreaks: Clinical presentation, sources and control of outbreak. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:1253-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA advises drug manufacturers that Burkholderia cepacia complex poses a contamination risk in non-sterile, water-based drug products. FDA. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-advises-drug-manufacturers-burkholderia-cepacia-complex-poses-contamination-risk-non-sterile, accessed on February 2, 2024.

- Microbial diversity in pharmaceutical product recalls and environments. PDA J Pharm Sci Technol. 2007;61:383-99.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]