Translate this page into:

Wide range of F cell levels in healthy Thai adults: Influence of Swiss-type hereditary persistence of foetal haemoglobin & β-haemoglobinopathy

For correspondence: Dr Thanusak Tatu, Department of Medical Technology, Division of Clinical Microscopy, Research Center for Hematology & Health Technology, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand e-mail: tthanu@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Swiss-type hereditary persistence of foetal haemoglobin (HPFH) has been shown to be responsible for the wide range of F cell levels in healthy Thai adults. However, a survey for F cells in healthy Thai adults has not been performed. This study was conducted to determine the F cell distribution in adult Thai blood donors and to assess the possible involvement of β-thalassaemia and haemoglobin E (HbE) carriers in increased HbF levels.

Methods:

Thai blood donors (n=375, 205 males and 170 females) were included in the study. Blood samples were collected for measuring haemoglobin (Hb) concentration and haematocrit (Hct) and F cell levels. Hb and Hct levels were determined by automated blood counter, while F cells were quantified by flow cytometric analysis of F cells stained by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti γ-globin monoclonal antibody. Finally, F cell levels were compared between blood samples having mean corpuscular volume (MCV) <80 fl and ≥80 fl as well as between β-haemoglobinopathies (HbE and β-thalassaemia carriers) and normal adults.

Results:

F cell levels varied markedly spanning 0.80-39.2 per cent with a positively skewed distribution. Thirty two per cent of these individuals had F cell levels more than the 4.5 per cent cut-off point. F cell levels in females were significantly higher than those in males (P<0.05). F cell levels in individuals having MCV <80 fl were significantly higher than those having MCV ≥80 fl (P<0.05). β-haemoglobinopathy (HbE and β-thalassaemia carriers) had significantly higher F cell levels than normal individuals (P<0.05).

Interpretation & conclusions:

The present results showed that besides Swiss-type HPFH, the β-haemoglobinopathy was expected to be involved in increased F cell levels in adult Thais. Thus, influence of β-haemoglobinopathy must be considered in interpreting F cell levels in area endemic of this globin disorder.

Keywords

ß-hemoglobinopathy

ß-thalassaemia

F cell

haemoglobinopathies

Swiss-type HPFH

Foetal haemoglobin or haemoglobin F (HbF) is the major haemoglobin (Hb) at the foetal stage of human development, constituting approximately 90 per cent of total Hb. At birth, HbF constitutes approximately 59±10 per cent of the total Hb and continues to gradually decline thereafter, reaching an adult level of <1 per cent by two years of age123. These small amounts of HbF are not evenly distributed, but confined to a subpopulation of erythrocytes termed 'F cells'. The F cell and HbF levels correlate well, and F cells at <4.5 per cent of total erythrocytes corresponding to HbF at 0.6 per cent are generally observed in normal individuals24.

Increased HbF and F cell levels can be observed in otherwise healthy adults in a condition known as 'hereditary persistence of foetal haemoglobin (HPFH)'2. Two types of HPFH, pancellular and heterocellular have been classified according to intraerythrocytic distribution of HbF2. The intraerythrocytic distribution of HbF is the characteristics of pancellular HPFH, whereas only a subpopulation of erythrocytes containing HbF are observed in the heterocellular type.

Swiss-type HPFH is the heterocellular HPFH which is characterized by a modest increase in HbF levels in healthy adults2. Although most of the HPFHs are not very common, the Swiss-type HPFH is frequently found in the general population as observed in 15 per cent of British twins and in 11.3-20.7 per cent of the Japanese individuals25. Increased HbF levels have been observed in both β-thalassaemia carriers and haemoglobin E (HbE) carriers67. A survey in Portugal among the β-thalassaemia carriers with increased HbF levels demonstrated significant association of high HbF trait with the XmnI-Gγ polymorphism and β-globin restriction fragment length polymorphism haplotypes8. In contrast, a survey among HbE carriers in southern Thailand showed that increased HbF in HbE carriers was accounted for by both theBCL11A gene and the XmnI-Gγ polymorphism9. Both β-thalassaemia and HbE carriers are common in Thailand10. Therefore, these carriers could be screened in a population survey for HbF/F cell levels in Thailand and probably cause a broad range of HbF/F cell distribution. However, a detailed analysis of these F cell levels has not been performed. Therefore, this study was aimed to determine the F cell distribution in Thai blood donors who represent healthy Thai adults. The possible involvement of HbE and β-thalassaemia carriers in increased F cell levels was also studied.

Material & Methods

Blood samples (3 ml) were collected in EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) from 375 blood donors (205 males and 170 females) at the Blood Bank Unit, Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand from May 2002 to May 2004. The ethics clearance for this study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand (number of 125/2002), and all participants signed the informed written consent.

Automated determination of haemoglobin concentration and haematocrit: Total haemoglobin concentration (Hb; g/dl), haematocrit (Hct; %) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV; fl) were determined using an automated blood cell analyzer (Sysmex KX-21 Hematology Analyzer; Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan).

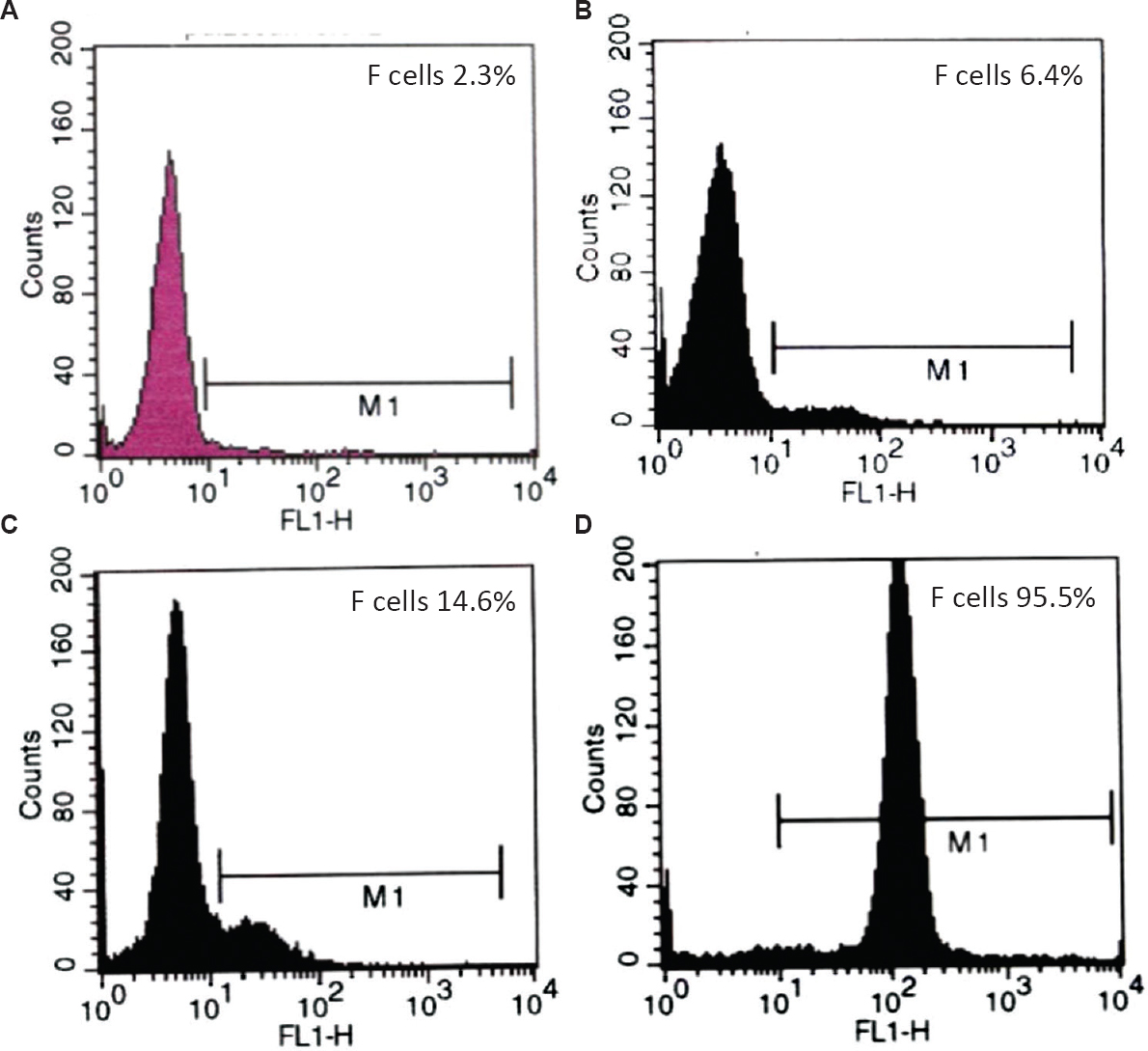

F cell enumeration: F cell levels were quantified by flow cytometric analysis of F cells after staining red blood cells (RBCs) in suspension with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-γ-globin monoclonal antibody (mAb) following the procedure described previously with some modification211. Briefly, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-washed RBCs (~130×106 RBCs) were fixed in 4.0 per cent (v/v) formaldehyde, permeabilized in cold acetone:distilled water mix and stained with FITC-conjugated mAb against human γ-globin chain (gift from Dr Swee Lay Thein of King's College School of Medicine, London). The stained erythrocytes (~2.6×106 RBCs) were then washed and finally stored in 1.0 ml of 1.0 per cent formaldehyde in 0.1 bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in PBS pH 7.4 for subsequent flow cytometric analysis (15,000 stained erythrocytes) using FACSCalibur™ coupled with CellQuest™ program (Becton-Dickinson, NJ, USA) (Fig. 1).

- Flow cytometric histogram of F cells in normal (A) and elevated F cell levels (B-D). B and C are representative histograms of moderately high F cell levels observed in adult with heterocellular hereditary persistence of foetal haemoglobin. D is a representative histogram of extremely high F cell levels observed in cord blood.

Identification of β-thalassaemia carriers and HbE carriers: β-thalassaemia and HbE carriers were identified from blood samples by cation exchange high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Primus Variant System 99™, Primus Corporation, Kansas, USA) following manufacturer's instruction. HbE and A2 were co-eluted in this system. Blood samples of HbE carriers have HbA and E (plus A2). In contrast, blood samples having Hb types of A2A with HbA2 between 3.5 and 10 per cent were diagnosed as β-thalassaemia carriers1.

Statistical analysis: The data were analyzed for mean, standard deviation, unpaired Student's t test and Mann-Whitney U-test using SPSS 7.5 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Levels of Hb, Hct and MCV: Hb, Hct and MCV levels in all as well as male and female blood donors are shown in Table. Hb and Hct levels were significantly higher in males than females (P<0.05). In contrast, MCV levels were significantly higher in females than males (P<0.05).

| Blood donors | Hb (g/dl) | Hct (%) | MCV (fl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (375) | 13.7±1.2 | 41.3±3.1 | 86.8±7.5 |

| Males (205) | 14.4±1.1* | 42.9±2.8† | 86.0±7.7 |

| Females (170) | 12.9±0.8 | 39.4±2.3 | 87.7±7.1$ |

Values are mean±SD. *,†P<0.05 compared to females $P<0.05 compared to males

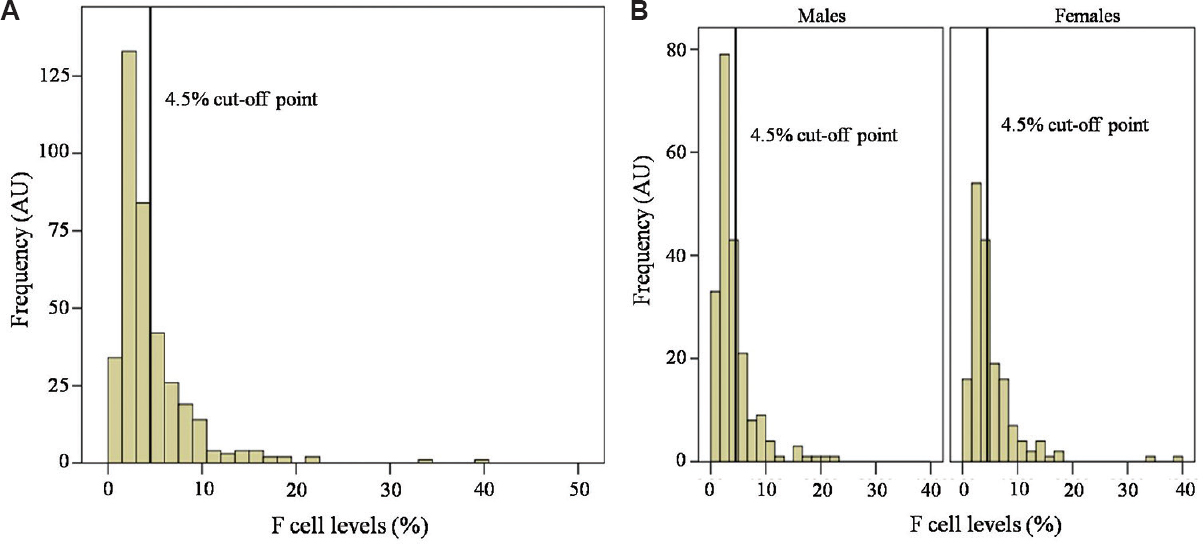

F cell distribution: F cell levels varied remarkably (0.8 - 39.2%) with positively skewed distribution in all individuals as well as in each gender (Fig. 2). One hundred and twenty individuals or 32 per cent had F cell levels ≥4.5 per cent, the cut-off point previously established in studies among British and Japanese12. Females had significantly higher F cell levels than males (5.1±4.8% vs. 4.1±3.5%).

- Distribution of F cell levels in 375 Thai blood donors (A) and in each gender (B). Note that the F cell distribution is wide and positively skewed. AU, arbitrary unit.

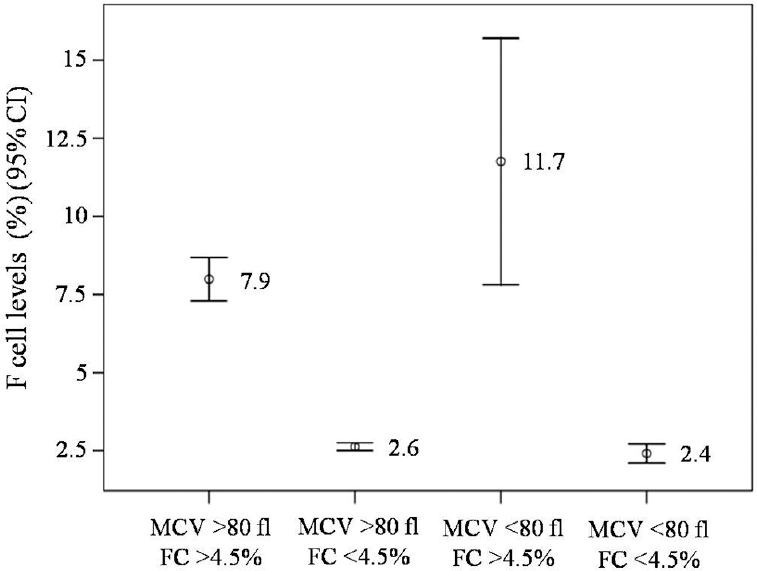

F cell levels in individuals with different MCV values: The individuals were classified by the MCV cut-off point of 80 fl for thalassaemia trait12. The first group comprised 324 individuals having MCV ≥80 fl and the second group consisted of 51 individuals having MCV <80 fl. Ninety nine individuals (30.5%) in the first group had high F cell levels (7.9±3.4%) compared to the remaining 225 individuals (69.5%) that had normal F cell levels (2.6±0.9%). In addition, 23 individuals (45.1%) in the second group had high F cell levels (11.7±9.1%), while the remaining 28 individuals (54.9%) had normal F cell levels (2.4±0.8%) (Fig. 3). The average F cell level of the second group (low MCV) was significantly higher than that ofthe first group (6.6±7.6 vs. 4.3±3.2, P<0.05).

- F cell levels in individuals having different mean corpuscular volume (MCV) values. Mean values are placed at the middle of each bar. Note that increased F cell levels are seen in both groups. FC, F cell.

F cell levels in β-haemoglobinopathies and normal: The individuals having MCV <80 fl had higher F cell levels than those having normal MCV values. F cell levels were compared between seven β-HbE and 32 normal individuals. It was found that F cell levels in these β-HbE were significantly higher than those in normal individuals (11.8±12.5% vs. 5.8±4.2%, P<0.05).

Discussion

In this study blood donors were used to represent healthy adults. All the individuals were not anaemic as shown by normal Hb/Hct levels. Thus, erythroid expansion should not be the cause of increased F cell production in these individuals2. Elevated F cell levels observed might have resulted from HPFH, β-haemoglobinopathies (β-thalassaemia and HbE carriers) and malarial selection, either alone or in combination.

The HPFH can be identified by measuring F cell levels by FACS analysis12. In contrast, identifying the HbE and β-thalassaemia carriers is conventionally performed by determining the Hb types and quantities using either cation-exchange HPLC13 or capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE)14. HbA2 levels of 2.6±0.36 and 5.5±1.26 per cent are observed in normal individuals and β-thalassaemia carriers, respectively. In contrast, HbE plus HbA2 of 27.8±7.50 per cent are characteristics of HbE carriers1415. The positively skewed distribution of F cell levels observed in this study was as expected. However, the presence of increased F cell trait observed in this study was higher than that demonstrated for the British and Japanese (32 vs. 10-20%)516. Thus, in addition to the Swiss-type HPFH, the β-HbE (β-thalassaemia and HbE carriers) and malarial selection were expected to be involved. Thailand is rich of β-HbE (particularly HbE and β-thalassaemia), the disorders accompanied by increased HbF and F cell levels due to an erythroid expansion17. Thus, F cell status in Thai healthy adults is expected to be affected by not only the Swiss-type HPFH but also by these two β-HbE.

The surveys have clearly demonstrated that not only erythroid expansion but also HPFH cause increased HbF/F cell production in the β-HbE89. The XmnI polymorphism has been shown to be the major genetic factor for the Swiss-type HPFH5. However, the Kruppel-like factor 1 (KLF1) was also found to be involved in this type of HPFH18. The KLF1 is, in fact, an erythroid transcriptional factor first described in 1993. Although being the multifunctional nuclear protein in erythroid cells, one of its important functions is to promote the γ to β-globin gene switch19. Thus, mutations of the KLF1 gene terminate or retard the transition from γ to β-globin gene expression, leading to persistent expression of the γ-globin gene of the Swiss-type HPFH18. KLF1 mutations were found to be common in β-thalassaemia endemic area in China20. Therefore, high F cell levels in β-thalassaemia, and HbE carriers, observed in this study, might also be accounted for by the KLF1 mutations, in addition to the XmnI polymorphism and the erythroid expansion. Study in detail is needed to elucidate this notion.

Ninety nine of 324 individuals (30.5%) having MCV ≥80 fl had increased F cell levels. These individuals were normal having less chance to be β-thalassaemia or HbE carriers. Therefore, in addition to the Swiss-type HPFH, malarial selection was expected to be involved in these individuals. Basically, RBCs containing high HbF are shown to have impaired cytoadherence property which reduces parasite density and ameliorates the clinical symptoms21. Thus, those having high HbF in the RBCs should be selected and survive as malaria is common in northern Thailand22.

In conclusion, this study showed that in addition to the Swiss-type HPFH, the β-HbE (β-thalassaemia, HbE) were possibly involved in increased F cell levels. Therefore, the β-thalassaemia and HbE need to be considered in interpreting the F cell status in patients living in areas endemic of these disorders. However, sample size of the β-thalassaemia and HbE carriers analyzed in this study was small. Therefore, a study with a large sample size of these disorders should be performed to confirm these findings. Malarial involvement of elevated F cell levels should also be investigated in detail.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks the Blood Bank Unit, Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand, for supporting blood collection. The author also thanks Dr Denis Sweatman, Department of Physics and Material Sciences, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, for English proofreading of this manuscript.

Financial support & sponsorship: This study was supported by a grant from Thailand Research Fund (Grant no. TRG4580026).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- The thalassaemia syndromes (4th ed). Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 2001.

- Phenotype-genotype relationships in monogenic disease: Lessons from the thalassaemias. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:245-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Control of foetal hemoglobin: New insights emerging from genomics and clinical implications. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R216-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic influences on F cells and other hematologic variables: A twin heritability study. Blood. 2000;95:342-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relevance of hemoglobin F measurement in the diagnosis of thalassaemias and related hemoglobinopathies. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:1797-801.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Swiss-type heterocellular HPFH from XmnI-gγ and HBBP1 polymorphisms on HbF, HbE, MCV and MCH levels in Thai HbE carriers. Int J Hematol. 2014;99:338-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymorphic variations influencing foetal hemoglobin levels: Association study in beta-thalassaemia carriers and in normal individuals of Portuguese origin. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2015;54:315-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative trait loci influencing Hb F levels in Southern Thai Hb E (HBB: C.79G>A) heterozygotes. Hemoglobin. 2018;42:23-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thalassaemia in Southeast Asia: Problems and strategy for prevention and control. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:647-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunochemical estimation of haemoglobin types in red blood cells by FACS analysis. Br J Haematol. 1994;87:125-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovering the genetics underlying foetal haemoglobin production in adults. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:455-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory investigation of hemoglobinopathies and thalassaemias: Review and update. Clin Chem. 2000;46:1284-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid diagnosis of thalassaemias and other hemoglobinopathies by capillary electrophoresis system. Transl Res. 2008;152:178-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prenatal and postnatal diagnoses of thalassaemias and hemoglobinopathies by HPLC. Clin Chem. 1998;44:740-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- X-linked dominant control of F-cells in normal adult life: characterization of the Swiss type as hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin regulated dominantly by gene(s) on X chromosome. Blood. 1988;72:1854-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ten novel mutations in the erythroid transcription factor KLF1 gene associated with increased foetal hemoglobin levels in adults. Haematologica. 2012;97:340-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. Nat Genet. 2010;42:742-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- KLF1 mutations are relatively more common in a thalassaemia endemic region and ameliorate the severity of β-thalassaemia. Blood. 2014;124:803-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- A role for foetal hemoglobin and maternal immune IgG in infant resistance to Plasmodium falciparum malaria. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14798.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of malaria in travellers to South-East Asia: Is local malaria transmission a useful risk indicator? Malar J. 2010;9:266.

- [Google Scholar]