Translate this page into:

Visual inspection of cervix with Lugol's iodine for early detection of premalignant & malignant lesions of cervix

Reprint requests: Dr Puneet K. Kochhar, F-3/17 Model Town-II, New Delhi 110 009, India e-mail: drpuneet.k20@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Majority of cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed at an advanced stage as cytology based screening programmes are ineffective in developing countries. The present study was done to look for carcinoma cervix and its precursors by visual inspection with Lugol's iodine (VILI), visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and Papanicolaou smear, and to analyse their sensitivity, specificity and predictive values using colposcopic directed biopsy as reference.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, 350 women were subjected to Pap smear, VIA, VILI and colposcopy. Cervical biopsy and endocervical curettage was taken from patients positive on any of these tests and in 10 per cent of negative cases.

Results:

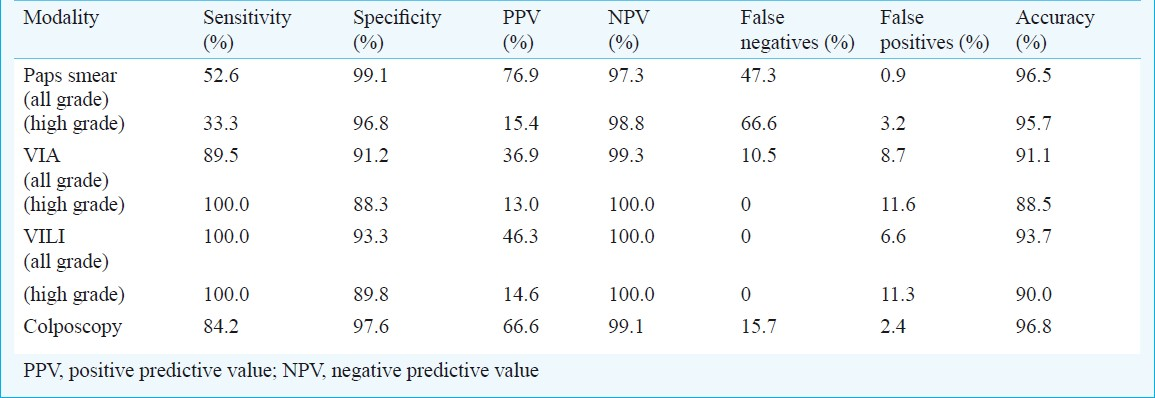

The Pap smear was abnormal in 3.71 per cent, including (2.85%), low grade (LSIL) and (0.85%) high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). Thirteen per cent of the patients were found to be positive by VIA and 11.71 per cent were positive on VILI. Sensitivity for VIA, VILI and Pap smear was 89.5, 100 and 52.6 per cent, respectively, while the specificity for VIA, VILI and Pap smear was 91.2, 93.3 and 99.1 per cent, respectively.

Interpretation & conclusions:

In low resource settings, cervical cancer screening by Pap smear can be replaced by visual methods like VILI, which has the highest sensitivity (100%) to detect any grade of dysplasia, and a good specificity (93.3%).

Keywords

Cervical cancer screening

early detection

Lugol's iodine

pap smear

VILI

visual inspection of cervix

Cervical cancer is the commonest malignancy found amongst Indian women and the third most common cancer in the world1. Over 5,00,000 new cases of invasive cervical cancer are diagnosed annually worldwide12. Although the incidence of cervical cancer has decreased in developed countries as a result of screening by cytology, it is still the single largest cause of lives lost to cancer in developing countries as cytology based screening programmes are almost non-existent and ineffective. Given that over 80 per cent of the population lives in rural areas, screening programmes need to work within this sector.

Visual methods like visual inspection of cervix with Lugol's iodine (VILI) are alternative screening modalities with the advantage that the results are immediately available and one can apply “see and treat” policy in suitable cases. However, whether VILI alone can be used for early detection of premalignant cervical lesions in low resource settings is yet to be determined.

The present study was aimed to assess the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of VILI as a tool for early detection of premalignant and malignant cervical lesions in low resource settings using colposcopy directed biopsy as gold standard. Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and Papanicollaou smear were also tested.

Material & Methods

This was a cross-sectional study carried out in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology of Lok Nayak Hospital, a tertiary level hospital in New Delhi, India, from January 2008 to February 2009. A total of 350 women were recruited from the gynaecologic out-patient department randomly. Pregnant women, women with active bleeding per vaginum, frank growth on cervix, post-hysterectomy patients, and women who had never been sexually active or had undergone prior treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or cancer cervix were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval of the study protocol was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi. After taking an informed consent from all women included, Pap smear was taken and visual inspection was done with 5 per cent acetic acid (VIA). Appearance of any distinct acetowhite areas in the transformation zone was considered as VIA positive. After 1-2 min of VIA, normal saline was applied to cervix and visual inspection after application of Lugol's iodine (VILI) was performed. Iodine uptake was noted as brown (positive uptake), yellow brown (partial uptake) and mustard yellow (no uptake). Areas of no uptake were considered as VILI positive while areas of partial uptake and positive uptake were considered as VILI negative. This was followed by colposcopy performed by the same observer in all cases after one hour or in the next visit.

Cervical biopsy and endocervical curettage (ECC) was taken from patients positive on any of these tests (n=58) and in 10 per cent of negative cases. Biopsies revealing CIN1 or worse lesions were considered as positive.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of the various tests described were analysed using colposcopic directed biopsy as the reference standard.

Results

Mean age of the patients was 34.1 ± 9.2 yr (range: 25-39 yr) and mean parity was 2.4 ± 0.9 (range: 0-5). The corresponding figures for patients with CIN were 33.4 ± 7.2 yr (range: 25-39 yr) and 2.9 ± 0.8 (range: 0-5).

The commonest presenting complaint was vaginal discharge (in 317/350; n=91% of the patients). Other presenting complaints were postcoital (17/350), intermenstrual (4/350), or postmenopausal (1/350), bleeding (5, 1 and 0.3%, respectively), pain lower abdomen (8/350; 2%) and pruritis vulvae (3/350; 0.8%). The commonest finding on per speculum examination was a normal looking cervix (seen in 155/350; 44.3% of patients) and the most common abnormality was an ectopy (89/350; 25.4%). However, in the CIN group, only 15.7 per cent (3/19) patients had a normal looking cervix; majority of patients (11/19; 57.9%) had an unhealthy cervix and 15.8 per cent (3/19) had a suspicious looking cervix.

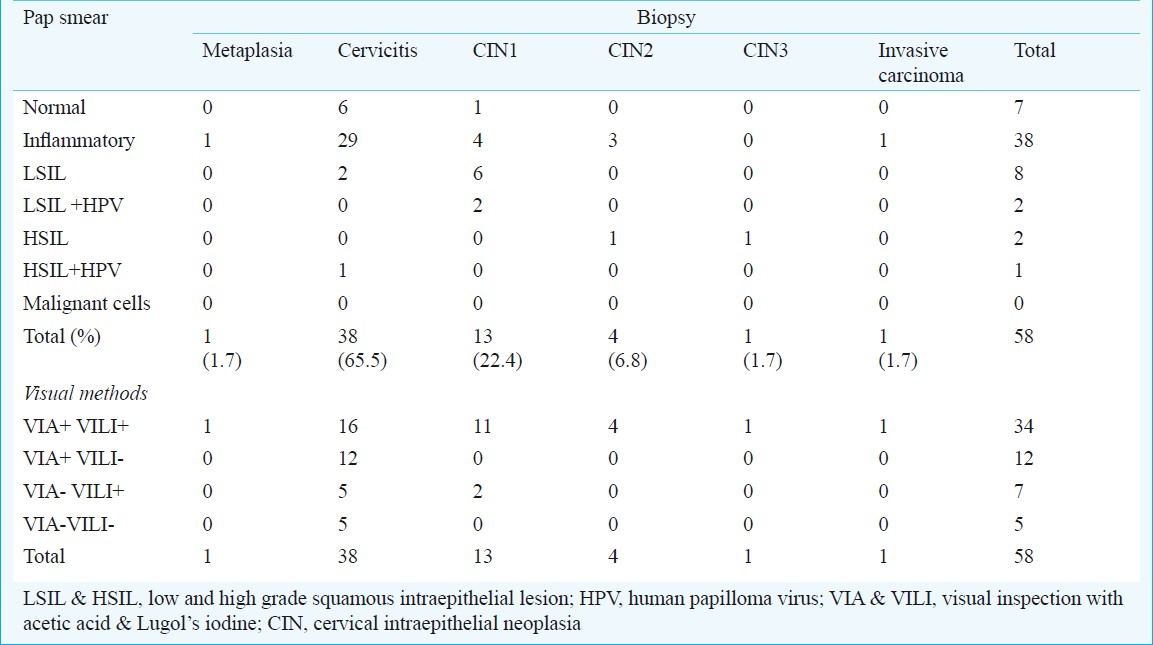

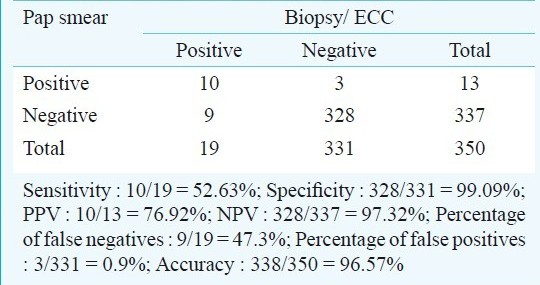

Pap smear was positive (ASCUS or worse) in 13 cases (3.71%), including 10 cases of LSIL and three of HSIL. Eight of the 38 cases reported as inflammatory smears were under-diagnosed by Pap smear (Table I). The cases missed by Pap smear were five cases of CIN1, three of CIN2 and one of invasive cancer. Thus, the sensitivity of Pap smear for detecting all grades of CIN was found to be 52.6 per cent with a high false negative rate of 47.3 per cent. The specificity was high at 99.1 per cent (Table IIa). The sensitivity to detect higher grade lesions was 33.3 per cent, while the specificity was 96.8 per cent.

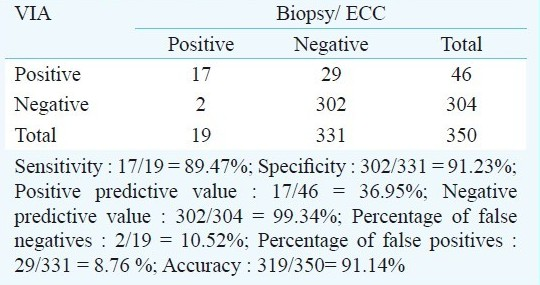

On visual inspection of cervix with 5 per cent acetic acid, 46 (13.14%) cases were VIA positive. Of these, 29 (62.8%) had benign histopathological changes on biopsy; 11 (23.9%) VIA positive cases had CIN1, four (8.6%) had CIN2, one case (2.0%) had CIN3 and one had invasive carcinoma. Of the 19 biopsy positive cases for CIN1 or worse, 17 were detected by a positive VIA test. Thus, VIA had a sensitivity and specificity of 89.5 and 91.2 per cent, respectively and a low false negative rate of 10.5 per cent (Table IIb). No case of CIN2 or CIN3 was missed by VIA. However, two cases which were recorded as VIA negative (because there was no distinct acetowhite area and an impression of metaplasia was made), were biopsied because of VILI positivity and found to have CIN1.

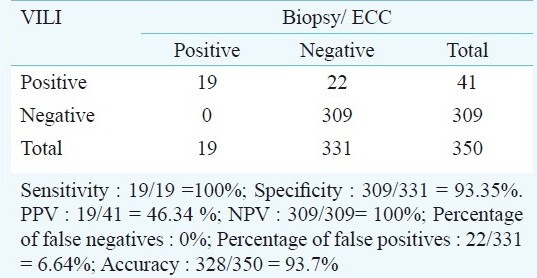

Forty one patients (11.71%) were VILI positive. All the biopsy positive cases (CIN1 or worse) were VILI positive (Table I). Of the 41 VILI positive cases, 13 were CIN1, four were CIN2, one was CIN3 and one had invasive carcinoma. The other 22 cases were benign on histopathology by biopsy, giving a positive predictive value of 46.3 per cent. For detecting all grades of CIN, VILI had a high sensitivity of 100.0 per cent and a specificity of 93.35 per cent (Table IIc).

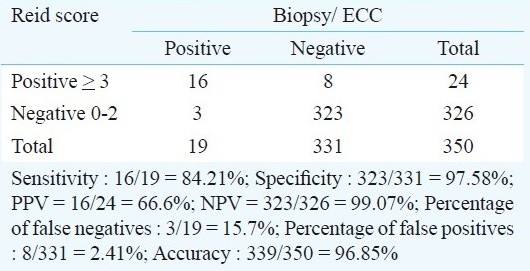

All 350 patients underwent colposcopic exami-nation. Majority of the patients (n=326, 93.14%) had a Reid index of 0-2, while 23 (6.5%) had a Reid index of 3-5 and only one patient had Reid index = 6. Considering a Reid index >3 as abnormal, test characteristics were calculated keeping biopsy as reference standard. The sensitivity of colposcopic examination was found to be 84.2 per cent, while the specificity was 97.6 per cent. The negative predictive value was 99.07 per cent and the accuracy of the test was 96.8 per cent (Table IId). The comparative analysis of VIA, VILI, Pap smear and colposcopy is shown in Table III.

Combination of various modalities

VIA + VILI: The sensitivity of the combined test was 89.47 per cent (identical to that of VIA alone, but lesser than that of VILI). The specificity of combined test was 93.17 per cent, which was greater than VIA alone but comparable to VILI. Thus, VILI can improve the specificity of VIA when used in combination.

VIA + Pap smear: When VIA was combined with Pap smear, the sensitivity was 47.36 per cent and the specificity was 99.09 per cent (markedly better than VIA alone). Therefore, combining Pap smear to VIA increased the specificity and helped in decreasing the number of biopsies required.

VILI + Pap smear: When VILI was combined with Pap smear, the sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values were 52.63, 99.09 and 77.0 per cent, respectively. The increase in sensitivity over the combination of VIA and Pap smear was not statistically significant. This combination also helped in decreasing unnecessary biopsies based on either test alone.

VIA + VILI + Pap smear: A combination of all the 3 tests i.e. VIA, VILI and Pap smear had the same test results as that of combination of VIA and Pap smear.

Discussion

Cervical cancer is a potentially preventable cancer. It is preceded by premalignant lesions which may take 5-15 ys to progress to invasive cancer. If detected and treated timely, pre-invasive disease has nearly 100 per cent cure rate with simple surgical procedure, while advanced cancers have less than 35 per cent survival rates3. However, in developing countries like India, universal screening has not been achieved. The main screening method (Pap smear) is available to a small percentage of population. Cytology based screening programmes are difficult to organize owing to limited infrastructure, trained personnel and funds4. It has been estimated that in India, even with a major effort to expand cytology services, it will not be possible to screen even one-fourth of the population once in a lifetime5. Moreover, screening programmes in India are mostly institution based and are restricted to urban centres6. Thus, in developing countries, there is a need for alternative strategies for early detection of premalignant cervical lesions.

In the current study, women from all the age groups were included. A large study done by Luthra et al7 revealed mean ages for mild, moderate and severe dysplasia to be 33.8, 35.2 and 40.2 years. In another study8, the average age of mild dysplasia was 31.4 years, severe dysplasia 34.3, carcinoma in situ 34.7 and invasive carcinoma 42.2 years. Therefore, screening for cervical carcinoma should start ideally at the onset of sexual activity and all women should be screened at least once by the age of 30-35 yr. Since visibility of the squamo-columnar junction is age related, a higher proportion of VIA-positive women are of lower age compared to women testing positive on cytology or HPV testing9.

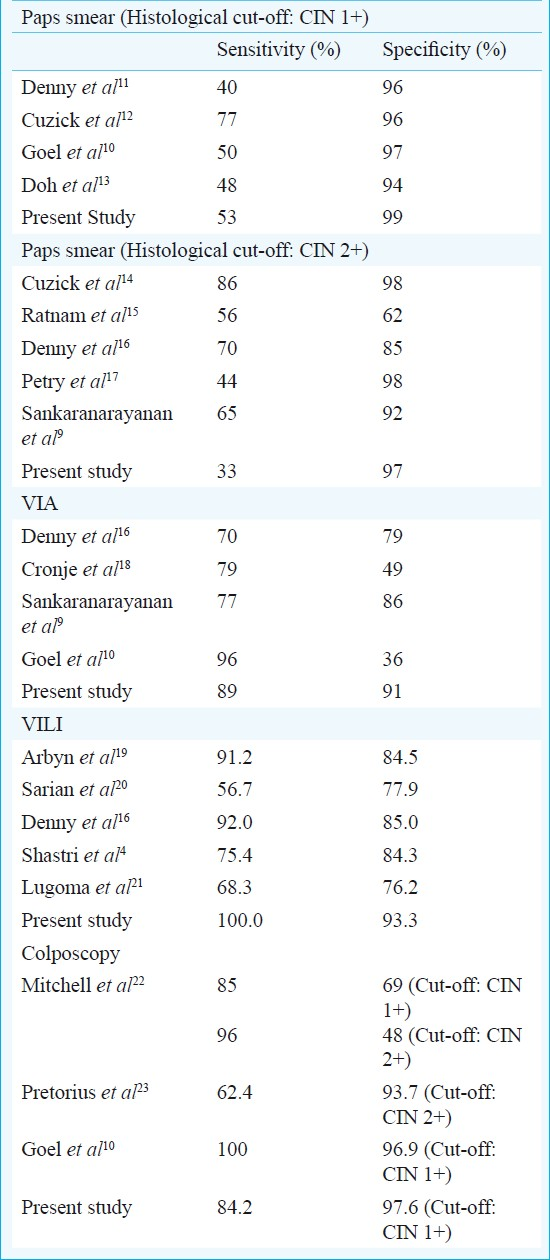

The occurrence of abnormal smears was 3.7 per cent in our study. This correlated well with the 1.5 to 5.4 per cent reported in previous Indian studies710. With CIN1 as cut-off, the sensitivity of Pap smear ranged from 40 to 77 per cent and for CIN2 as cut-off, the sensitivity ranges from 33 to 86 per cent (Table IV). This low sensitivity results in a high false negative rate ranging from 6-55 per cent2425. The sensitivity of Pap smear has been found to be lower in developing countries, probably due to the large percentage of inflammatory smears which may mask mild dysplasia. A multi-centric study in India, evaluating the accuracy of conventional cytology, found sensitivity to vary from 37.8-81.3 per cent for ASCUS, 28.9-76.9 per cent for LSIL and 24.4-72.3 per cent for HSIL, between the centres26.

Pap smear has various limitations besides low sensitivity. These include the need for repeated visits for screening, collection of report, evaluation of abnormal results and treatment, and requirement for laboratory infrastructure, highly trained cytopathologists and staff for large scale screening. This hinders the use of Pap smear on a large scale in low resource settings. This has led to the need for alternate methods which are cheap, easy to perform, can be done by paramedical workers and give immediate results.

Unaided visual inspection of cervix (downstaging) to identify cases suspicious for precancer and cancer has low positive predictive value (2-6%)27. Luthra et al7 found that nearly 44 per cent dysplasias, 13.6 per cent carcinoma in situ and 4.3 per cent of invasive carcinomas may be found in an apparently normal looking cervix. However, in cases of higher grade dysplasias and malignancy there is higher percentage of clinically abnormal cervix28. The same was observed in our study. Acetowhite areas delineated on VIA may represent cervicitis, HPV infection, premalignant or malignant lesions. The prevalence of VIA positive cases has been reported to vary from 12.5 to 53.0 per cent9101618. This wide variation is because of different criteria used to specify test positivity. The VIA positive rate in our study was similar to other Indian studies (12 to 16%)910.

VIA is more sensitive than conventional cytology in detecting intraepithelial lesions, though it has a lower specificity. The sensitivity and specificity of VIA in our study was comparable to that of other studies (Table IV). The large variation in these results indicates that several variables affect the test characteristics of visual inspection with acetic acid. These are observer training, criteria for test positivity, inter-observer variation, light source, presence of co-existing infection, inflammation and metaplasia.

Iodine negative areas include columnar epithelium (lacking glycogen), patchy uptake peripheral areas due to cervicitis, and immature metaplasia. These can be mistaken by inexperienced workers as VILI positive. Mustard yellow areas with distinct borders suggest more severe disease. The colour changes with VILI are more easy to appreciate than the changes after VIA2029.

Advantages of VILI are that it is easily available, can be easily performed by paramedical workers and doctors, test results are immediately available and hence “see and treat” policy can be used, low cost, need not be freshly prepared (as compared to acetic acid), and longer shelf life (1 month) as compared to acetic acid. In the present study, results of VILI positive CIN1 and CIN2 cases corroborated well with other studies, while the percentage of VILI positive cases which turned out to be benign on histopathology was lower2021. This low test positivity could be due to the fact that only mustard yellow areas were taken as VILI positive, and partial iodine uptake was considered as VILI negative. The visual impression in VILI negative cases was based on the charts published by IARC27. In a study conducted in 11 centres in India and Africa, VILI had a greater sensitivity (91%) compared to VIA (75%)30. In another study conducted at Mumbai4, sensitivity of VILI (75.4%) was higher, though not statistically significant, compared to VIA (59.7%), visual inspection of cervix with acetic acid under magnification (VIAM) (64.9%), HPV (62%) and cytology (57.4%). The specificities were 84.3 per cent for VILI, 88.4 per cent for VIA, 86.3 per cent for VIAM, 93.5 per cent for HPV and 98.6 per cent for cytology4. Among the visual tests assessed, VILI seemed to be particularly promising, detecting 75 per cent of all cases of HSIL compared to VIA and VIAM, which detected less than two-thirds of cases. Another advantage of visual techniques is a very high negative predictive value (>99%). A woman negative by VIA/VILI need not further undergo any investigation. However, these women are advised to undergo a VIA or VILI after a minimum interval of 3 years. Only 10-15 per cent women who are test positive with visual techniques require further evaluation5.

In conclusion, in low resource settings, screening of carcinoma cervix by Pap smear can be replaced by cheaper and easily available visual methods like VILI, which has the high sensitivity to detect any grade of dysplasia, with a reasonable specificity. Even when screening with Pap smear is available, it should be combined with visual screening methods like VILI, as many cases of CIN missed by Pap smear were picked up by the visual tests, and combined testing reduced the number of biopsies taken based on either test alone.

References

- Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-917.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. In: Comprehensive cervical cancer control: A guide to essential practice. Geneva: WHO; 2006. p. :13-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concurrent evaluation of visual, cytological and HPV testing as screening methods for early detection of cervical neoplasia in Mumbai, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:186-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical cancer screening in India: Strategies revisited. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61:34-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing the feasibility of single lifetime PAP smear evaluation between 41-50 years of age as strategy for cervical cancer control in developing countries from our 32 years of experience of hospital-based routine cytological screening. Diagn Cytopathol. 2004;31:376-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history of precancerous and early cancerous lesions of the uterine cervix. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:226-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening of cervical neoplasia: Results from a multicentre study in India. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:341-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid for cervical intraepithelial lesions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direct visual inspection for cervical cancer screening: An analysis of factors influencing test performance. Cancer. 2002;94:1699-707.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of women who test positive for high-risk types of human Papillomavirus: the HART study. Lancet. 2003;362:1871-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual inspection with acetic acid and cytology as screening methods for cervical lesions in Cameroon. Int J Gynaecol Cancer. 2005;89:167-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomavirus testing for primary screening of cervical cancer precursors. Cancer Epideimiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:945-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of alternative methods of cervical cancer screening for resource-poor settings. Cancer. 2000;89:826-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inclusion of HPV testing in routine cervical cancer screening for women above 29 years in Germany: results for 8466 patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1570-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparision of four screening methods for cervical neoplasia in a developing country. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;188:395-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pooled analysis of the accuracy of five cervical cancer screening tests assessed in eleven studies in Africa and India. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:153-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of visual inspection with acetic acid, Lugol's iodine, cervical cytology and HPV testing as cervical cancer screening tools in Latin America. J Med Screen. 2005;12:142-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual inspection as a cervical cancer screening method in a primary health care setting in Africa. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1389-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colposcopy for the diagnosis of squamous intraepithelial lesions: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:626-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colposcopically directed biopsy, random cervical biopsy and endocervical curettage in the diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia II or worse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:430-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of screening error for observed detection rates in repeated cervical cytology. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1974;119:953-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of conventional cytology: Results from a multicentre screening study in India. J Med Screen. 2004;11:77-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- IARC handbooks of cancer prevention: Cervix cancer screening. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2005.

- Visual screening for cervical cancer screening: Evaluation by doctor versus paramedical worker. Indian J Cancer. 2004;41:32-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- IARC Multicentre Study Group on Cervical Cancer Early Detection.Accuracy of visual screening for cervical neoplasia: Results from an IARC multicentre study in India and Africa. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:907-13.

- [Google Scholar]