Translate this page into:

Uromodulin rs4293393 T>C variation is associated with kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes

Reprint requests: Dr Ashok Kumar Yadav, Department of Nephrology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India e-mail: mails2ashok@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Uromodulin, a UMOD gene encoded glycoprotein is synthesized exclusively in renal tubular cells and released into urine. Mutations lead to uromodulin misfolding and retention in the kidney, where it might stimulate cells of immune system to cause inflammation and progression of kidney disease. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified UMOD locus to be associated with hypertension and diabetic nephropathy (DN). In this study, we investigated the association between rs4293393 variation in UMOD gene and susceptibility to kidney disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods:

A total of 646 individuals, 208 with T2DM without evidence of kidney disease (DM), 221 with DN and 217 healthy controls (HC) were genotyped for UMOD variant rs4293393T>C by restriction fragment length polymorphism. Serum uromodulin levels were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results:

A significant difference was found in genotype and allelic frequency among DM, DN and HC. TC+CC genotype and C allele were found more frequently in DN compared to HC (33.9 vs 23.0%, P=0.011 and 20.1 vs 12.9%, P=0.004, respectively). Compared to DM, C allele was found to be more frequent in individuals with DN (20.1 vs 14.7%, P=0.034). Those with DN had higher serum uromodulin levels compared to those with DM (P=0.001). Serum uromodulin levels showed a positive correlation with serum creatinine (r=0.431; P<0.001) and negative correlation with estimated glomerular filtration rate (r=−0.423; P<0.001).

Interpretation & conclusions:

The frequency of UMOD rs4293393 variant with C allele was significantly higher in individuals with DN. UMOD rs4293393 T>C variation might have a bearing on susceptibility to nephropathy in north Indian individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Keywords

Diabetic nephropathy

polymorphism

uromodulin

Uromodulin, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein, is exclusively expressed in the thick ascending loop of Henle1 and distal convoluted tubule2 of the mammalian kidney. It is exclusively produced in the kidney and secreted into the urine3. The biological function of uromodulin remains elusive. It can bind with immunoglobulin G, complement 1q and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) suggesting a role in innate immunity456. In animal studies, immunization with homologous urine or purified uromodulin resulted in cellular immune response and tubulointerstitial nephritis7. This led to the suggestion that interstitial release of uromodulin after tubular damage can act as a signal to recruit immune cells7. Moonen et al8 demonstrated the inability of uromodulin to bind with native cytokines in vitro. In contrast to these studies, El-Achkar et al9 proposed a renoprotective role of uromodulin in ischaemia-reperfusion injury, using Tamm-Horsfall protein knockout mouse model.

Uromodulin-induced renal inflammation and damage may be due to intracellular retention or delayed translocation to outer membrane. Variations can cause delay in protein export by increasing retention time in the endoplasmic reticulum101112. UMOD mutations have been shown to be associated with urinary concentration defect, salt wasting, hyperuricaemia, gout, hypertension and end-stage renal disease (ESRD)13. Uromodulin has been linked to medullary cystic kidney disease, glomerulocystic kidney disease, urinary tract infections, nephrolithiasis and acute kidney injury9111314.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shown that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in UMOD gene (rs12917707 and rs42993393) were associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD)151617. The BPGen consortium identified an association of the rs13333226 minor allele with higher estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and reduced risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease18. UMOD gene missense mutation p.V458L was associated with reduced glomerular filtration rate in healthy individuals19. Another study20 showed an association between UMOD SNP rs13333226 and hypertension and CKD in Swedish individuals with type 2 diabetes. This study was undertaken to evaluate the frequency of UMOD rs4293393 T>C in north Indian individuals with type 2 diabetes and to examine its association with kidney disease.

Material & Methods

This study was done in the department of Nephrology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, a large tertiary care hospital in north India during July 2011 to December 2014. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee, and all individuals provided written informed consent. A total of 429 (290 male and 139 female) patients with type 2 diabetes diagnosed according to the World Health Organization criteria21 were recruited consecutively from the Nephrology and Endocrinology Clinic. Inclusion criteria for diabetic nephropathy (DN) (n=221) were individuals with diabetic retinopathy, eGFR <60 ml/min and/or proteinuria >500 mg/day, sustained for more than or equal to three months in the absence of another cause, and inclusion criteria for diabetic without nephropathy (n=208) were individuals with disease duration greater than five years, normal blood pressure, eGFR >60 ml/min and urinary albumin <150 mg/day or negative on dipstick urinary analysis. Also, 217 healthy individuals were also included with no diabetes or kidney disease. These healthy individuals were healthy prospective voluntary kidney donors.

Determination of UMOD rs42993393 T>C genotype: Peripheral leucocytes were isolated22 from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-treated whole blood obtained from each patient, and genomic DNA was extracted using Qiagen DNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of UMOD gene. The primer set used for the PCR amplification was: forward 5’ - GTGCAAATTTATTTCGCCTCCA -3’ and reverse 5’ - GGACTACCTTCTGGTTCTGACTTTCA -3’. Amplification was done for 30 cycles with the following cycle parameters: 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 59°C for 30 sec, followed by extension at 72°C for 30 sec and final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. SNP was analyzed with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) using Msp1 restriction enzyme (New England BioLab Inc., USA). Msp1 specifically cut at the CˇCGG to produce two products of size 87 base pair (bp) and 27 bp, which were resolved in 2 per cent agarose gel along with 100 bp DNA ladder and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

The data obtained from RFLP were further confirmed by nucleotide sequencing (Applied Biosciences, Germany) of gene fragment (167 bp), which was amplified using specific primer set: forward 5’ -GGACCTCCCAGTCATCAGAC-3’ and reverse 5’ -GGCACCCTTCTGAAACACCC-3’. All primers were designed using https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/ and synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich, USA.

Serum level of uromodulin was measured in 40 DM, 80 DN and 40 healthy control (HC) individuals by enzyme immunoassay using a commercial kit (USCN Life Science, USA) as per the manufacturer's instructions. This kit detected <5.8 pg/ml without any cross-reactivity.

Statistical analysis: Assuming difference in minor allele frequency of 12 per cent between controls and individuals with DN, a sample size of 209 individuals in each group was required to achieve power of 80 per cent at alpha of 5 per cent. Data are presented as mean±standard deviation unless indicated otherwise. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was calculated for SNP in each group using Michael H. Court's (2005–2008) online calculator (http://www.tufts.edu/~mcourt01/Documents/Court%20lab%20-%20 HW%20calculator.xls). Difference between groups were tested using Student's t test and Chi square test for continuous and nominal variables, respectively, while skewed distributed parameters were analyzed with Mann–Whitney U-test. The allelic and genotype association of SNP were evaluated by Pearson's Chi-square test; and odds ratio (OR) and 95 per cent confidence intervals were determined. For comparison of more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was used. Correlation analysis was done using Spearman's rank correlation. Two-tailed P<0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago IL, USA).

Results

Table I describes the clinical features of study individuals. There was no difference in age and gender distribution between groups. The duration of diabetes was longer and the prevalence of neuropathy and retinopathy was higher in individuals with kidney disease.

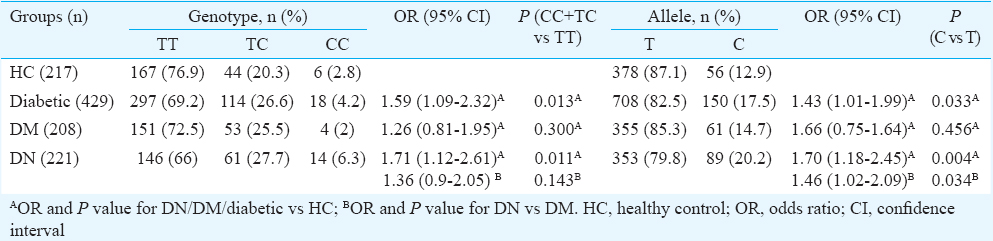

UMOD rs42993393 T>C and risk of kidney disease: Studied SNP followed Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in healthy individuals (P=0.15, χ2=2.08) and all individuals with diabetes (P=0.10, χ2=2.68). Compared to healthy individuals, those with diabetes had a higher frequency of CC+TC genotypes (P=0.013; OR=1.59) and C allele (P=0.033, OR=1.43). This was primarily driven by individuals with kidney disease. The C allele and CC+TC genotype frequency in DN individuals were significantly higher (P=0.003; OR=1.70 and P=0.01; OR=1.71, respectively) compared to HC, whereas those with diabetes but no kidney disease showed a similar genotype distribution as HC (P=0.30; OR=1.26 and C: P=0.57; OR=1.11, respectively). Upon comparison of DM and DN, those with DN showed a significantly higher frequency of C allele (P=0.03; OR=1.46) (Table II).

Serum uromodulin: Individuals with DN exhibited elevated serum uromodulin level compared to those with DM (72.32±37.76 pg/ml vs 49.32±25.61 pg/ml, P=0.001) and HC (51.18±19.91, P=0.001). Serum uromodulin levels showed a positive correlation with serum creatinine (r=0.431, P<0.001) and inverse correlation with eGFR (r=−0.423, P<0.001) in diabetic individuals.

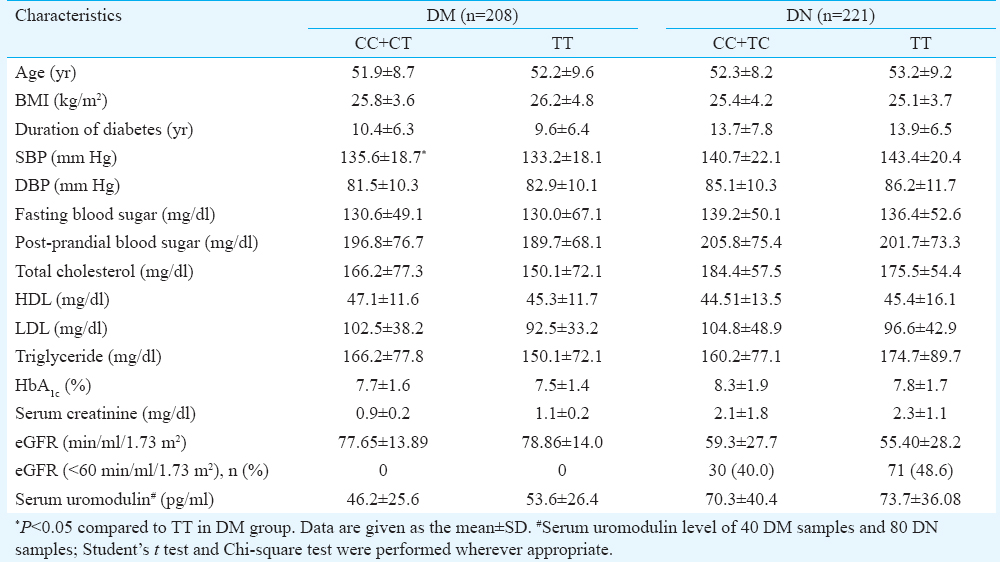

Genotype-phenotype and UMOD rs42993393 T>C: The biochemical and clinical parameters and serum uromodulin were compared based on genotype distribution. None of the clinical parameters defining the renal complications or serum uromodulin level showed significant association with C allele (Table III).

Discussion

In this study an attempt was made to link UMOD gene variant rs42993393 with kidney disease among north Indian individuals with type 2 diabetes. This SNP, located 550 bp upstream to uromodulin transcription site, has been linked to kidney disease in a couple of studies162324. The frequency of C allele and TC+CC genotype was found to be different in the overall population of the individuals with diabetes compared to HCs. Further, the frequency of C allele was higher in DN compared to HC and DM individuals, whereas there was no difference between HC and DM. Our results indicate that C allele and genotype with C allele may confer the risk of kidney disease in individuals with diabetes.

Gudbjartsson et al16 found an association of T allele with elevated serum creatinine, uric acid and lower risk of calcium-containing kidney stone formation. They also demonstrated that hypertensive and type 2 diabetes patients carrying T allele had higher serum creatinine after the age of 50 yr compared to those without this variant. Köttgen et al23 investigated the functional link between this SNP and uromodulin secretion. They found that increased secretion of uromodulin preceded the development of CKD. A study showed that rs4293393 TT genotype was independently associated with reduced eGFR24. The genotype and allelic frequency distribution of this SNP in our population were in contrast with previous reports162324. However, other studies have shown either no difference in frequency of rs42993393 genotype/allele in patients with urinary tract infection in multi-centric cohort study25 or protection against kidney stone16.

Apart from rs42993393 variation in UMOD, some other variations have also been studied in diseases with renal impairment. Gómez et al19 found a missense mutation p.V458L in which leucine variant was more frequent in individuals with reduced GFR as compared to healthy individuals with normal GFR. Associations of UMOD rs13333226 G allele with hypertension, CKD20 and ESRD26 have been reported. However, Cui et al27 reported association of rs13333226G allele with slower decline in renal function in individuals with CKD. A study of UMOD variant rs12917707 in Italian diabetic cohort, no association was found with renal function28. In another study, there was no association between rs12917707 and IgA nephropathy or progression to ESRD29. Observations from these studies suggest that UMOD might be a strong genetic determinant of kidney function in some diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, but this association is modified by heterogeneity in populations.

In the present study it was found that the level of serum uromodulin in individuals with DN was raised compared to DM and HC individuals. However, the level was not affected by the distribution of rs4293393 genotype. An earlier study in non-diabetic individuals suggested that lower urinary and higher serum levels of uromodulin were associated with kidney disease30. Prajczer et al30 investigated the serum and urinary uromodulin levels in 77 CKD patients and found a significant association of eGFR with urinary uromodulin and a trend showing inverse correlation with serum uromodulin. Other studies2431 showed an association of eGFR with plasma/urine uromodulin level. Our results were consistent with these studies.

The inverse relationship between serum uromodulin and eGFR suggests that uromodulin may accumulate as the GFR goes down. Alteration in the accumulation of uromodulin in the tubulointerstitial compartment can also affect serum uromodulin levels. High interstitial uromodulin concentrations can induce inflammation. In one study, serum uromodulin concentrations correlated with levels of proinflammatory cytokines, viz. TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-830.

The limitations of our study were lack of treatment data and cross-sectional design of the study. Caution is needed while attributing causality to the relationship between uromodulin and development of kidney disease as our study infers just association. Although we did not find an association between the presence of C/T allele and uromodulin levels in those with diabetes but no kidney disease at the time of the study, it would be interesting to follow these individuals to see if they develop kidney disease with increasing duration of diabetes.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from Department of Science and Technology, New Delhi, Government of India (Grant No: SR/SO/HS/08/2009).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Ultrastructural localization of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein (THP) in rat kidney as revealed by protein A-gold immunocytochemistry. Histochemistry. 1985;83:531-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrastructural localization of Tamm-Horsfall protein in human kidney using immunogold electron microscopy. Histochem J. 1988;20:156-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- The rediscovery of uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall protein): From tubulointerstitial nephropathy to chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80:338-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein): A renal ligand for lymphokines. Science. 1987;237:1479-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Binding of Tamm-Horsfall protein to complement 1q measured by ELISA and resonant mirror biosensor techniques under various ionic-strength conditions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:474-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein binds IgG with high affinity. Kidney Int. 1993;44:1014-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein links innate immune cell activation with adaptive immunity via a Toll-like receptor-4-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:468-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Native cytokines do not bind to uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein) FEBS Lett. 1988;226:314-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tamm-Horsfall protein protects the kidney from ischemic injury by decreasing inflammation and altering TLR4 expression. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F534-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- A cluster of mutations in the UMOD gene causes familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy with abnormal expression of uromodulin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2883-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Allelism of MCKD, FJHN and GCKD caused by impairment of uromodulin export dynamics. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3369-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uromodulin mutations causing familial juvenile hyperuricaemic nephropathy lead to protein maturation defects and retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2963-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mutations of the UMOD gene are responsible for medullary cystic kidney disease 2 and familial juvenile hyperuricaemic nephropathy. J Med Genet. 2002;39:882-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ablation of the Tamm-Horsfall protein gene increases susceptibility of mice to bladder colonization by type 1-fimbriated Escherichia coli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F795-802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic loci influencing kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:373-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of variants at UMOD with chronic kidney disease and kidney stones-role of age and comorbid diseases. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001039.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple loci associated with indices of renal function and chronic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:712-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genome-wide association study of blood pressure extremes identifies variant near UMOD associated with hypertension. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Next generation sequencing search for uromodulin gene variants related with impaired renal function. Mol Biol Rep. 2015;42:1353-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uromodulin gene variant is associated with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1731-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new, fast and convenient method for layering blood or bone marrow over density gradient medium. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:686-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uromodulin levels associate with a common UMOD variant and risk for incident CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:337-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical, genetic, and urinary factors associated with uromodulin excretion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:62-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary proteins, vitamin D and genetic polymorphisms as risk factors for febrile urinary tract infection and relation with bacteremia: A case control study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121302.

- [Google Scholar]

- A single nucleotide polymorphism in the UMOD promoter is associated with end stage renal disease. BMC Med Genet. 2016;17:95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-nucleotide polymorphism of the UMOD promoter is associated with the outcome of chronic kidney disease patients. Biomed Rep. 2015;3:588-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- The rs12917707 polymorphism at the UMOD locus and glomerular filtration rate in individuals with type 2 diabetes: Evidence of heterogeneity across two different European populations. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016 pii: gfw262

- [Google Scholar]

- UMOD polymorphism rs12917707 is not associated with severe or stable IgA nephropathy in a large Caucasian cohort. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for a role of uromodulin in chronic kidney disease progression. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1896-903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma uromodulin correlates with kidney function and identifies early stages in chronic kidney disease patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3011.

- [Google Scholar]