Translate this page into:

Toxigenic Clostridium difficile isolates from clinically significant diarrhoea in patients from a tertiary care centre

Reprint requests: Dr. Chetana Vaishnavi, Department of Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India e-mail: cvaishnavi@rediffmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Clostridium difficile is the primary cause of hospital-acquired colitis in patients receiving antibiotics. The pathogenicity of the organism is mainly due to the production of toxins. This study was conducted to investigate the presence of toxigenic C. difficile in the faecal samples of hospitalized patients suspected to have C. difficile infection (CDI) and corroborating the findings with their clinical and demographic data.

Methods:

Diarrhoeic samples obtained from 1110 hospitalized patients were cultured for C. difficile and the isolates confirmed by phenotypic and molecular methods. Toxigenicity of the isolates was determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for toxins A and B. Details of patients included in the study were noted and analyzed.

Results:

Of the 1110 patients (mean age 39±19.6 yr), 63.9 per cent were males and 36.1 per cent were females. The major antibiotics received by the patients were nitazoxanide (23.9%), penicillins/penicillin combinations (19.0%), quinolones including fluoroquinolones (13.1%), carbapenems (11.5%), glycopeptides (11.0%) and cephalosporins (8.4%). The clinical symptoms predominantly present were watery diarrhoea (56.4%), fever (40.0%) and abdominal pain (35.3%). The underlying diseases were gastrointestinal disorders (52.6%), followed by cancers (13.2%), surgical conditions (8.3%), and hepatic disorders (8.0%). Of the 174 C. difficile isolates, 54.6 per cent were toxigenic. Toxigenic C. difficile was present in all patients with surgical conditions, 65.2 per cent with cancers and 57.1 per cent with gastrointestinal disorders.

Interpretation & conclusions:

C. difficile was found to be an important cause of gastrointestinal infections in hospitalized patients with underlying diseases and on antibiotics. Clinical conditions of the patients correlating with toxigenic culture can be an important tool for establishing CDI diagnosis.

Keywords

Antibiotic exposure

clinical conditions

Clostridium difficile

toxigenic culture

underlying diseases

Clostridium difficile is an important Gram-positive spore-bearing enteric pathogen associated with extensive morbidity and mortality. It is recognized as the major cause of hospital-acquired colitis in patients receiving broad-spectrum antimicrobials1 or other drugs such as proton pump inhibitors (PPI)2, immunosuppressives3 and cancer therapeutics4. C. difficile is responsible for up to 20-25 per cent cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea5. Many of the patients experience recurrence of diarrhoea after successful management of the initial episode. C. difficile infection (CDI) is also responsible for the exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease6.

Clinically various signs and symptoms present during CDI help in diagnosing the disease. Diarrhoea is generally a side effect of many commonly used antibiotics. However, the overgrowth of drug-resistant C. difficile can result in nosocomial diarrhoea. The hallmark of CDI is thus the presence of profuse watery, green foul-smelling or bloody diarrhoea along with fever and abdominal cramps. C. difficile pathogenesis is mainly due to the production of toxin A and toxin B, the two major toxins responsible for extensive damage to the gastrointestinal wall and accumulation of luminal fluid. Both the toxins open up the tight junctions between the intestinal epithelial cells of the gut, aid vascular permeability and cause haemorrhage, leading to bloody diarrhoea7. Acute infection can lead to ulceration of the colon and excretion of mucous in the faeces. The diagnosis of CDI is largely based on the detection of C. difficile toxins in the faecal samples by enzyme immunoassays (EIA). However, toxin detection by EIA is suboptimal as regards to sensitivity and specificity and depends on the presence of toxins in the stool samples. It has been estimated that if the prevalence of C. difficile toxins in faecal samples is <10 per cent, the positive predictive value of EIA dips to <50 per cent and therefore, it cannot be expected to be a reliable diagnosis for clinical management7. The culture of faecal samples for toxigenic C. difficile is expected to be confirmatory and a more reliable diagnostic test for CDI8.

Frequent outbreaks of CDI can occur due to the presence of C. difficile along with the number of people receiving antibiotics and other drugs in the hospitals. In this prospective study, toxigenic culture for C. difficile was done from faecal samples of patients suspected to have CDI. The clinical and demographic data of the patients were also analyzed for corroboration.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted from June 2012 to December 2014 in Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, a tertiary care centre at Chandigarh, India, to which patients are referred from different parts of north India (Chandigarh, Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Western parts of Uttar Pradesh and some parts of Rajasthan). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents/guardians in case of minors.

A total of 1110 hospitalized patients who developed diarrhoea after >72 h of admission and suspected of CDI were enrolled for investigation. Diarrhoea was defined as the occurrence of three or more loose stools per day lasting for at least two days. Patients with incomplete data, pregnant women and children less than two years of age were excluded from the study.

Clinical and demographic analysis: Data of the patients including clinical diagnosis, age, sex, frequency and duration of diarrhoea, stool consistency and presence of blood and mucous in the stool were recorded. These patients admitted to various wards (Gastroenterology, Surgery, ICU, Advanced kidney unit, Hepatology, male medical ward, female medical ward, Advanced pediatric centre, Transplant, Emergency) of the hospital were undergoing treatment for underlying disease conditions. Information on antibiotics and other drugs received by them during the past two weeks was noted at the time of sample collection. The patients were evaluated for other signs and symptoms of CDI inclusive of fever and pain abdomen. The patients were categorized according to their age into the following four groups: (i) Paediatric group: This group included patients between 2 and 18 yr (n=189); (ii) Young adult group: Patients above 18 yr and up to 45 yr (n=504) were included in this group; (iii) Middle age group: This group comprised patients above 45 yr and up to 65 yr (n=342); and (iv) Geriatric group: Patients above 65 yr (n=75) were placed in this group.

Toxigenic culture of Clostridium difficile: Single faecal samples from patients suspected of CDI were received in the department of Gastroenterology (Division of Microbiology) of the Institute. The specimens were initially enriched in Robertson's Cooked Meat Medium (HiMedia, Mumbai) and then cultured on Columbia blood agar medium (HiMedia) containing 0.1 per cent sodium taurocholate anaerobically for isolation of C. difficile. After identification of isolates by cultural appearance, Gram staining, ultraviolet fluorescence and biochemical tests, these were further checked using polymerase chain reaction with specific primers for amplifying triose-phosphate isomerase gene, a housekeeping gene for C. difficile910.

A single colony of C. difficile thus identified was grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (HiMedia) anaerobically for 48 h. The growth was centrifuged at 604 g for 5 min, and the supernatant was used for the detection of C. difficile toxins A and B using commercially available ELISA kit (TechLab, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The results were read in an ELISA reader (Tecan Infinite F50, Austria) at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis: The data were entered into database programme and analyzed by SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All the categorized age groups were compared using non-parametric Pearson Chi square, and parametric data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Parametric data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) and non-parametric data as proportion.

Results

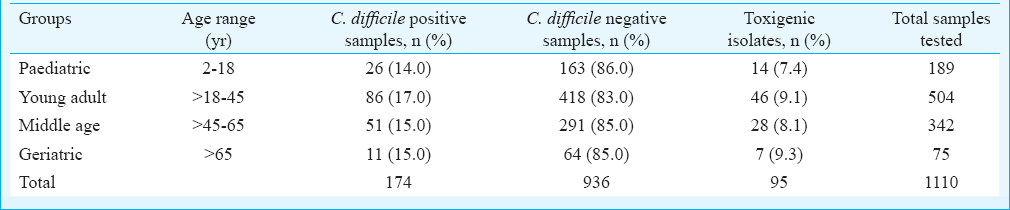

Of the 1110 patients analyzed in the study, 709 (63.9%) were males and 401 (36.1%) females (M:F=1.8:1) with age ranging from 2 to 95 yr (mean age±SD: 39±19.6 yr). The highest number of patients was enrolled in the young adult group (n=504, 45.5%; age, 18-45 yr) whereas the geriatric group had the lowest number of patients (n=75, 6.8%; age, 65-69 yr). There was a significant difference (P<0.05) between the mean age of different groups. However, no significant difference was observed between genders amongst the different groups.

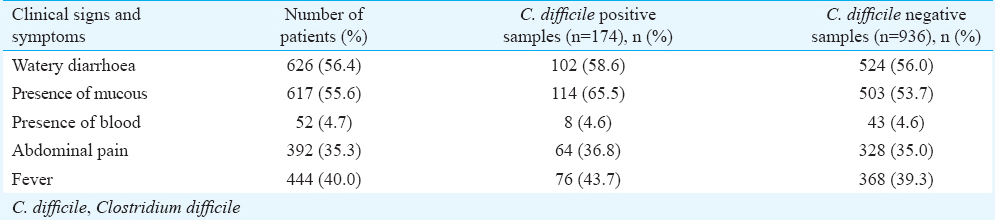

Predominant clinical symptoms present in the patients were watery diarrhoea in 626 (56.4%), pain abdomen in 392 (35.3%) and fever in 444 (40.0%). Bloody diarrhoea occurred in 52 (4.7%) patients and mucous was present in 617 (55.6%) of the faecal samples (Table I). The duration of diarrhoea was 7.5±11.9 days, and was not different in various age groups. The frequency of diarrhoea was 6.74±4.2 times/day. A significant difference (P<0.05) was observed between the presence of abdomen pain among the groups.

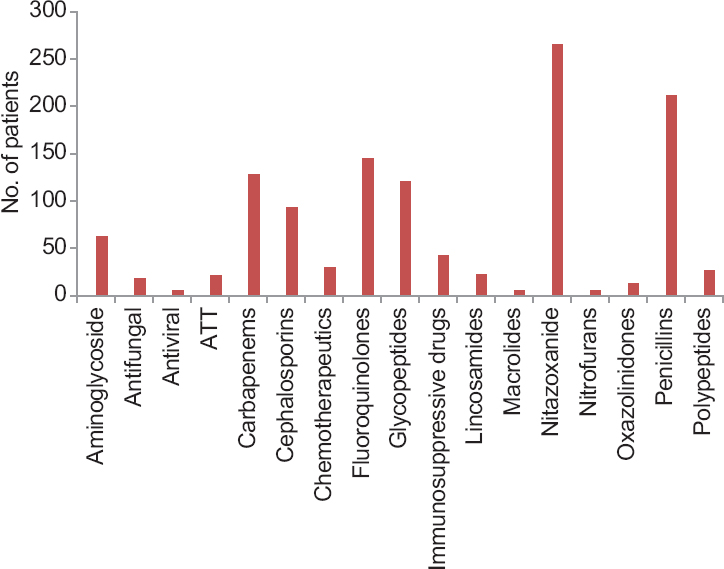

Use of antibiotics and other drugs: Categorization of antibiotics and other drugs received by patients are shown in Fig. 1. Of the 1110 patients, 79.3 per cent (n=880) were on antibiotics, and amongst them, 48.8 per cent (429/880) were on more than one antibiotic. Multiple usage of antibiotics was significant (P<0.001) compared to patients using single antibiotic or no antibiotic. The major antibiotic groups in use were nitazoxanide (23.9%, n=210), penicillins/penicillin combinations (19.0%, n=167), quinolones including fluoroquinolones (13.1%, n=115), carbapenems (11.5%, n=101), glycopeptides (11.0%, n=96) and cephalosporins (8.4%, n=74). In the present study, apart from antibiotics, 2.3 per cent (n=26) of the patients were on PPIs, 3.9 per cent (n=43) on immunosuppressive drugs such as wysolone and tacrolimus and 2.7 per cent (n=30) on chemotherapeutics. Antifungals and antivirals were also received by some patients.

- Categorization of antibiotics and other drugs received by patients. ATT, antitubercular treatment; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Underlying diseases: The main underlying diseases in the patients were gastrointestinal disorders (52.6%, n=584), cancers (13.2%, n=147), surgical conditions (8.3%, n=92), hepatic disorders (8.0%, n=88), blood disorders (4.5%, n=50), renal disorders (3.6%, n=40), respiratory disorders (3.2%, n=36), neurological disorders (2.4%, n=27), tuberculosis (2.0%, n=23), cardiac disorders (1.3%, n=14) and skin infections (0.8%, n=9) (Fig. 2).

- Underlying diseases of the patients admitted to the hospital. GI, gastrointestinal.

Toxigenic Clostridium difficile: The 95 per cent confidence interval (95% CI) for main outcome parameter i.e., C. difficile positivity was 13.62-17.90. C. difficile was isolated from 174 (15.7%) of the 1110 stool samples. C. difficile isolate positivity was 13.8 per cent in paediatric group, 17.0 per cent in young adult group, 15.0 per cent in middle age group and 14.7 per cent in geriatric group. There was no significant difference in the rate of C. difficile positivity and negativity among the genders. The mean age of patients with C. difficile isolates (n=174) and those negative for C. difficile (n=936) was 40±19 and 37±19 yr, respectively. There was no significant difference between the mean age of patients with C. difficile isolates and those negative for C. difficile. Table I shows the presence of C. difficile isolates in relation to clinical symptoms.

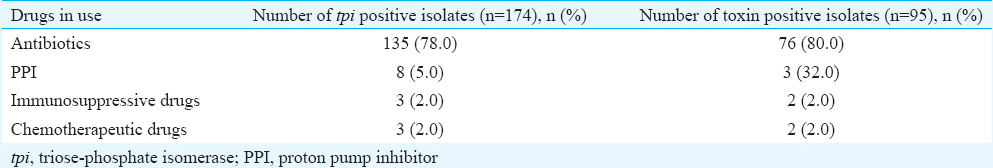

Toxigenic C. difficile comprised 95/174 (54.6%) isolates and the remaining 79 isolates were non-toxigenic. On intergroup comparison, toxigenic C. difficile was present in 14 of 26 (53.8%) in paediatric group, 46 of 86 (53.5%) in young adult group, 28 of 51 (55.0%) in middle age group and 7 of 11 (63.6%) in geriatric group (Table II). Presence of toxigenic C. difficile isolates was not significant between any group. Toxigenic C. difficile isolated from patients with watery diarrhoea were 56.0 per cent, with mucous in stool 54.4 per cent, with abdominal pain 59.3 per cent and with fever 49.0 per cent. All (100%) patients who underwent surgery were positive for toxigenic C. difficile, followed by patients with cancers (65.2%) and gastrointestinal disorders (57.1%). Toxigenic C. difficile isolates in relation to antibiotics were found in 80.0 per cent (n=76), in patients on PPIs 32.0 per cent (n=3) and in 2.0 per cent (n=2) each receiving immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutics drugs (Table III).

Discussion

The most common antibiotics implicated in hospital-acquired CDI include cephalosporins, ampicillin/amoxicillin and clindamycin even though all antibiotics have been implicated at one time or the other11. In the present study, administration of multiple antibiotics was found to be significant compared to patients using single or no antibiotic.

Administration of non-antibiotic medications such as PPI, immunosuppressive drugs and anticancer drugs to hospitalized patients is also a risk factor for acquiring CDI12. PPI contributes to the pathogenesis of CDI by inhibition of gastric acid secretion and reduction in pH of the gut2. In the present study, 2.3 per cent patients were on PPIs and C. difficile was isolated in 5.0 per cent of them, of which 32.0 per cent were toxigenic. The risk for CDI in patients exposed to immunosuppressive drugs is due to blunted ability to mount immune responses in them13. In our study, 2.0 per cent of the patients were exposed to immunosuppressive drugs and toxigenic C. difficile was isolated from faecal specimens of all of them. Again, chemotherapeutic drugs though possess antibacterial properties towards the gut flora, allow C. difficile colonization, thereby increasing the risk for CDI412. Severe CDI has been reported in patients receiving chemotherapy for ovarian malignancies14.

The signs and symptoms of CDI include inflammation of the bowel, abdominal pain, fever and diarrhoea. In an earlier study, we observed diarrhoea (90.2%), abdominal pain (36.5%) and fever (40.6%) as the predominant clinical symptoms present in CDI patients of the region15. In the present study, though only patients with nosocomial diarrhoea were included for investigation, fever was also found to be one of the most significant clinical symptoms followed by abdomen pain in toxigenic C. difficile-positive patients. Clinically significant diarrhoea evokes a suspicion of CDI in hospital settings and patients with severe CDI can have more than ten bowel movements per day16. In this study, the mean frequency of diarrhoea was 6.7 times per day.

Watery diarrhoea can be taken as the clinical standard for suspecting CDI16 whereas mucous or blood in stool is uncommon and therefore, not significant17. More than 50.0 per cent of the patients had watery diarrhoea in our study, which was significant between the different groups of study. Blood in stool was found in 88.0 per cent of the patients with toxigenic C. difficile. In the absence of diarrhoea, patient with recent antibiotic exposure and abdominal pain also raises suspicion of CDI16. Gogate et al18 found no relation with the presence of abdominal pain in CDI patients.

Severe underlying illness19 and surgical procedures have a significant correlation with CDI20. Zhu et al21 recommended regular faecal culture of C. difficile and toxin A/B test for prevention of CDI in cancer patients. The present study showed predominant toxigenic C. difficile in all (100%) patients who underwent surgery, followed by patients with cancers (65.2%) and gastrointestinal disorders (57.1%). This indicates the high-risk areas for nosocomial spread of C. difficile isolates where the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, immunosuppressive drugs and chemotherapeutics is widespread.

Brazier et al22 reported patients >65 yr to be more at risk with as many as 10 per cent of them being colonized with C. difficile. Studies from India have reported difference in mean age with varying male-female ratio in CDI patients11182324252627. The present study was consistent with those reported by others as no significance was observed between genders amongst the different age groups. Presence of toxigenic C. difficile isolates was higher in the males, but was not significantly associated with gender and could be due to more number of male patients present in the study population.

The reasons for lesser frequency of CDI in India could be due to frequent use of freely available metronidazole, incomplete antibiotic treatment, a good immune response towards C. difficile and high-fibre diet consumption. Apart from these, absence of virulent NAP1 could also contribute to lesser prevalence of CDI28. Limited documentation of culture or toxin proven CDI in India could also be because of inadequate facilities for culturing anaerobic pathogens in many of the hospitals29. Although, in the present study, it was not possible to classify the cases as hospital-acquired or community-associated CDI, the study had several advantages. It was a prospective study which employed a reference standard method for the detection of toxigenic C. difficile and the results correlated with the clinical data. Presence of C. difficile toxins in stool confirms the diagnosis of CDI16, but toxin assays should not be used as standalone tests as some patients with CDI may not have a detectable level of toxins in their faeces30. Due to the unstable nature of C. difficile toxins in non-preserved faecal samples and due to degradation of toxins during transportation at room temperature, there is increased possibility of false-negative results19. Thus, toxigenic culture and clinical information would be useful to help the clinician to establish a CDI diagnosis accurately31. The major limitation of the study was that the duration of antibiotic exposure could not be evaluated.

In conclusion, our study showed that C. difficile was an important cause of gastrointestinal infections in hospitalized patients with underlying diseases, even though some of the representative symptoms of CDI might be absent. This study showed that C. difficile was positive in 15.7 per cent of stool samples. The data may have major public health implications in planning treatment strategies and prevention of spread of the infection. No comparison of sensitivity was made in the study about any diagnostic test. Clinical conditions of the patients correlating with toxigenic culture can be a valuable tool for establishing the diagnosis of CDI. However, a high degree of clinical suspicion is required for proper surveillance of this organism to reduce its incidence and prevent its spread.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi, India, for funding the project (Grant No. 27(0259)/12/EMR-II), and thank Sarvshri Prashant Kapoor and Gurinder Singh Cheema for technical assistance and Dr. Ajay Prakash Patel for statistical evaluation.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- What have we learnt about antimicrobial use and the risk for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea? J Pharm Practice. 2008;21:346-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proton pump inhibitor therapy is a risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:613-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of biotherapeutics on cyclosporin-induced Clostridium difficile infection in mice. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:832-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The evolution of Clostridium difficile infection in cancer patients: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and guidelines for prevention and management. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2012;7:157-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clostridium difficile: Old and new observations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:S24-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous assays for Clostridium difficile and faecal lactoferrin in ulcerative colitis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:13-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection by toxin detection kits: A systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:777-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a plea for culture. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt 2):187-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surveillance for antibiotic resistance in Clostridium difficile strains isolated from patients in a tertiary care center. Adv Microbiol. 2015;5:336-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- PCR detection of Clostridium difficile triose phosphate isomerise (tpi), toxin A (tcdA), toxin B (tcdB), binary toxin (cdtA, cdtB), and tcdC genes in Vhembe District, South Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:577-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clostridium difficile toxin and faecal lactoferrin assays in adult patients. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1827-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Established and potential risk factors for Clostridum difficile infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009;27:289-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for management of Clostridium difficile infection in immunosuppressed patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:750-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis associated with paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 1999;9:512-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and demographic profile of patients reporting for Clostridium difficile infection in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:326-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical recognition and diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Suppl 1):S12-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic role of stool culture & toxin detection in antibiotic associated diarrhoea due to Clostridium difficile in children. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:518-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical spectrum & pathogenesis of Clostridium difficile associated diseases. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:487-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of Clostridium difficile in surgical patients in the United States. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2007;8:557-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea among cancer patients. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2014;36:773-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of toxin A negative/B positive Clostridium difficile strains. J Hosp Infect. 1999;42:248-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Clostridium difficile in hospitalised patients with acute diarrhoea in Calcutta. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9:16-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing pattern of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea in a tertiary care hospital: A 5 year retrospective study. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:377-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clostridium difficile infection at a tertiary care hospital in South India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61:804-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and clinical course of Clostridium difficile infection in a tertiary-care hospital: A retrospective analysis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:89-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea in a tertiary care hospital. J Assoc Physicians India. 2012;60:26-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and molecular types of Clostridium difficile isolates from faecal specimens of patients in a tertiary care centre. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:1297-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection and characterization of Clostridium difficile from patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in a tertiary care hospital in North India. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 12):1657-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Newer diagnostic methods in Clostridium difficile infection. J Gen Practice. 2014;2:2-5.

- [Google Scholar]