Translate this page into:

The need for obtaining accurate nationwide estimates of diabetes prevalence in India - Rationale for a national study on diabetes

Reprint requests: Dr V. Mohan, Director & Chief of Diabetes Research, Madras Diabetes Research Foundation & Dr. Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre, Who Collaborating Centre for Noncommunicable Diseases, Prevention & Control, 4, Conran Smith Road, Gopalapuram, Chennai 600 086, India e-mail drmohans@diabetes.ind.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

According to the World Diabetes Atlas, India is projected to have around 51 million people with diabetes. However, these data are based on small sporadic studies done in some parts of the country. Even a few multi-centre studies that have been done, have several limitations. Also, marked heterogeneity between States limits the generalizability of results. Other studies done at various time periods also lack uniform methodology, do not take into consideration ethnic differences and have inadequate coverage. Thus, till date there has been no national study on the prevalence of diabetes which are truly representative of India as a whole. Moreover, the data on diabetes complications is even more scarce. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a large well-planned national study, which could provide reliable nationwide data, not only on prevalence of diabetes, but also on pre-diabetes, and the complications of diabetes in India. A study of this nature will have enormous public health impact and help policy makers to take action against diabetes in India.

Keywords

Complications

diabetes

India

nationwide estimates

prevalence

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is growing rapidly worldwide and is reaching epidemic proportions12. It is estimated that there are currently 285 million people with diabetes worldwide and this number is set to increase to 438 million by the year 20303. The major proportion of this increase will occur in developing countries of the world where the disorder predominantly affects younger adults in the economically productive age group4. There is also consensus that the South Asia region will include three of the top ten countries in the world (India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) in terms of the estimated absolute numbers of people with diabetes3.

Although the exact reasons why Asian Indians are more prone to type 2 diabetes at a younger age and premature cardiovascular disease (CVD) remain speculative, there is a growing body of evidence to support the concept of the “Asian Indian Phenotype”5. This term refers to the peculiar metabolic features of Asian Indians characterized by a propensity to excess visceral adiposity, dyslipidaemia with low HDL cholesterol, elevated serum triglycerides and increased small, dense LDL cholesterol, and an increased ethnic (possibly genetic) susceptibility to diabetes and premature coronary artery disease56.

However, to view it in the proper perspective, the estimates regarding the number of people with diabetes in India are derived from a few scattered studies conducted in different parts of the country. There have been a few multi-centre studies such as the ICMR studies conducted in 19797 and 19918, National Urban Diabetes Survey (NUDS) in 20019, the Prevalence of Diabetes in India Study (PODIS) in 200410 and the WHO-ICMR NCD Risk factor Surveillance study in 200811. However, to date, there has been no national study which has looked at the prevalence of diabetes in India as a whole, covering all the States of the country or indeed, even in any single s0 tate with comprehensive urban and rural representation. In this article we review the published studies on the prevalence of diabetes and its complications in India and make a case for the need for a truly representative national study on the prevalence of diabetes in India.

The rise of non communicable diseases in India

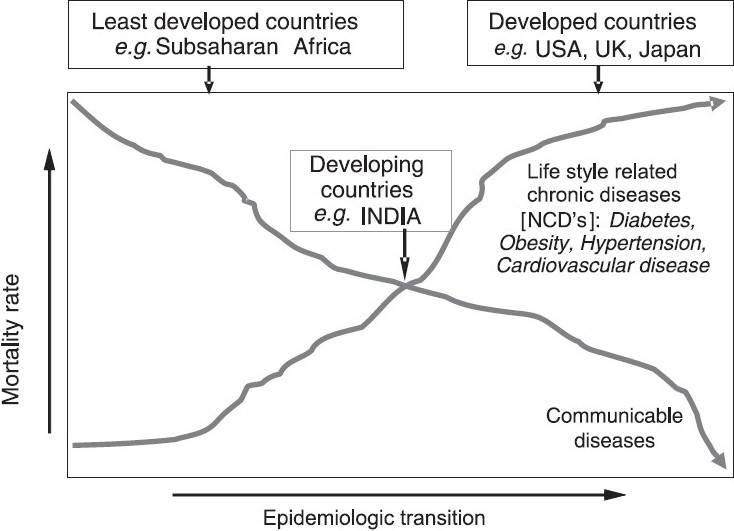

In countries like the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom and Japan, the prevalence of communicable diseases is much lower compared to chronic non-communicable diseases (NCD). In India, as in other low and middle income countries, diabetes and other NCDs are relatively overshadowed by the continued burden of communicable and nutrition-related diseases. While these health threats are still present (albeit, slowly decreasing), the rise of NCDs has been rather rapid. According to the World Health Report 200512, NCDs already contribute to 52 per cent of the total mortality in India and these figures are expected to increase to 69 per cent by the year 203013. Therefore, countries like India are currently facing an epidemiologic transition with a ’double burden’ of disease as shown in Fig. 1.

- Epidemiologic transition of communicable vs non-communicable diseases.

Globally, many of the risk factors for NCDs are lifestyle related and can be prevented. Ebrahim & Smeeth et al14 conclude that NCDs in low and middle income countries are a priority and that it would be a serious mistake to ignore their prevention and control. Another study15 which looked at the burden of NCDs in South Asia reports that ‘research and surveillance is urgently needed with new studies following more rigorous and standardized methods to assess the true extent and impact of NCDs in South Asia’.

The World Health Organization is urging health decision makers to develop effective prevention strategies to halt the rising trend of NCDs through the control of risk factors. Although most of the developed world has reacted by instituting pragmatic measures for risk factor control, the global burden of NCDs continues to grow. This is largely because developing countries like India provide the bulk of numbers of individuals with diabetes and other NCDs and in most developing countries the focus is still on infectious diseases and NCDs continue to be neglected. Thus, there is an urgent need for strategies to detect and control diabetes and other NCDs in developing countries.

Epidemiological studies in India

Ancient Indian texts make mention of the disease “Madhumeha” which would correspond to the modern term “Diabetes mellitus”, suggesting that diabetes must have been present in India even before 2500 BC. Although, there is no evidence as to how prevalent the condition was, a recent article hypothesizes that it could have been quite common in India, even in ancient times16.

Tables I17–66 and II7–1167 list the published studies on the prevalence of diabetes in India till date. As shown in Table II, there are only six studies which have sampled respondents at multiple locations. The ICMR survey done in the 1970s studied urban and rural areas but was limited to six regions7. Given the major socio-demographic and economic changes as well as technological advances in the past 30 years, most of this data are outdated and not applicable to India’s current population. The National Urban Diabetes Survey (NUDS) investigated prevalence of diabetes in 6 large metropolitan cities (“metros”) of India in 2001, but there was no rural component9. The Prevalence of Diabetes in India Study (PODIS) included smaller towns and villages but excluded the metros and big cities1068. The WHO-ICMR NCD Risk Factor Surveillance Study described the self-reported prevalence of diabetes in 6 centers, but no objective blood sugar testing was done11.

| Region | Urban | Rural | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Place | Year of publication | n | Age (yr) | Method adopted for diagnosis | Prevalence (%) | n | Age (yr) | Method adopted for diagnosis | Prevalence (%) | |

| Northern region: | ||||||||||

| Berry et al, Chandigarh17 | 1966 | 3846 | 30+ | US | 2.9 | - | - | - | - | |

| Gour, Varanasi18 | 1966 | 2572 | 10+ | US | 2.7 | - | - | - | - | |

| Datta et al, Lucknow19 | 1973 | 2190 | 20+ | RBG | 1.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ahuja et al, Delhi20 | 1974 | 2783 | 15+ | RBG | 2.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Varma, Delhi21 | 1974 | 2291 | 20+ | RBG | 2.7 | - | - | - | - | |

| Varma et al, Delhi22 | 1986 | 6878 | 20+ | K | 3.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Tiwari & Bissaraya, Rewa23 | 1988 | - | - | - | - | 15000 | - | RBG | 1.9 | |

| Wander et al, Punjab24 | 1994 | - | - | - | - | 1100 | 30+ | K + PG | 4.6 | |

| Zargar et al, Srinagar25 | 2000 | 1538 | 40+ | K + F+ PG* | 5.2 | 4045 | 40+ | - | 4.0 | |

| Misra et al, Delhi26 | 2001 | 532 | 18+ | K + F | 10.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Gupta et al, Jaipur27 | 2003 | 1091 | 20+ | K + F | 12.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Gupta et al, Jaipur28 | 2004 | 458 | 20+ | K + F | 16.8 | - | - | - | - | |

| Agrawal et al, Rajasthan29 | 2004 | - | - | - | - | 782 | 20+ | - | 1.8 | |

| Prabhakaran et al, Delhi30 | 2005 | 2122 | 20-59 | K+ F+ PG | 15.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Gupta et al, Jaipur31 | 2007 | 1127 | 20+ | K + F | 20.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Kokiwar et al, Nagpur32 | 2007 | - | - | - | - | 924 | 30+ | K+ F+ PG | 3.7 | |

| Agrawal et al, Rajasthan33 | 2007 | - | - | - | - | 2099 | 20+ | - | 1.7 | |

| Southern region: | ||||||||||

| Rao et al, Hyderabad34 | 1966 | 21396 | 20+ | US | 4.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Viswanathan et al, Chennai35 | 1966 | 5030 | 20+ | US | 5.6 | - | - | - | - | |

| Datta et al, Pondicherry36 | 1966 | 2694 | 20+ | US | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | |

| Rao et al, Hyderabad37 | 1972 | - | - | - | - | 2006 | 20+ | US | 2.4 | |

| Vigg et al, Hyderabad38 | 1972 | - | - | - | - | 847 | 10+ | RBG | 2.5 | |

| Parameswara, Bangalore39 | 1973 | 25273 | 5+ | RBG | 2.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Murthy et al, Tenali40 | 1984 | - | - | - | - | 848 | 15+ | RBG | 4.7 | |

| Ramachandran et al, Kudremukh41 | 1988 | 678 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 5.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ramaiya et al, Gangavati42 | 1990 | - | - | - | - | 765 | 30+ | K+ F + PG | 2.2 | |

| Ramachandran et al, Chennai43 | 1992 | 900 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG* | 8.2 | - | ||||

| Ramachandran et al, Sriperumbudur43 | 1992 | - | - | - | - | 1038 | 20+ | K + F+ PG* | 2.4 | |

| Patandin et al, North Arcot44 | 1994 | - | - | - | - | 467 | 40+ | K + PG* | 4.9 | |

| Ramachandran et al, Chennai45 | 1997 | 2183 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 11.6 | - | - | - | - | |

| Bai et al, Chennai46 | 1999 | 1198 | NA | K+ F+ PG | 7.6 | - | - | - | - | |

| Kutty et al, Trivandrum47 | 2000 | 518 | 20+ | RBG* | 12.4 | - | - | - | - | |

| Joseph et al, Trivandrum48 | 2000 | 206 | 19+ | K+ PG | 16.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Asha Bai et al, Chennai49 | 2000 | 26066 | 20+ | K | 2.9 | - | - | - | - | |

| Mohan et al, Chennai50 | 2001 | 1262 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 12.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Mohan et al, Chennai51 | 2006 | 2350 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 15.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Chow et al, Godavari52 | 2006 | - | - | - | - | 4535 | 30+ | F* | 13.2 | |

| Menon et al, Kochi53 | 2006 | 3069 | 18-80 | K+ PG* | 19.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Ramachandran et al, Chennai54 | 2008 | 2192 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 18.6 | - | - | - | - | |

| Eastern region: | ||||||||||

| Tripathy et al, Orissa55 | 1971 | - | - | - | - | 2447 | 10+ | RBG | 1.2 | |

| Chhetri et al, Kolkata56 | 1975 | 4000 | 20+ | RBG | 2.3 | - | - | - | - | |

| Shah et al, Guwahati57 | 1998 | 1016 | 20+ | K+ PG | 8.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| Singh et al, Manipur58 | 2001 | 1664 | 15+ | K+ PG | 4.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Kumar et al, Kolkata59 | 2008 | 2160 | 20+ | K+ F* | 11.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Western region: | ||||||||||

| Patel et al, Mumbai60 | 1963 | 18243 | 20+ | US | 1.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| KEM Hospital, Mumbai61 | 1966 | 3200 | 20+ | RBG | 2.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Gupta et al, Ahmedabad62 | 1978 | 3516 | 15+ | RBG | 3.0 | - | - | - | - | |

| Patel, Bhadlan63 | 1986 | - | - | - | - | 3374 | 10+ | RBG | 3.8 | |

| Iyer et al, Bardoli64 | 1987 | - | - | - | - | 1348 | All | RBG | 4.4 | |

| Iyer et al, Mumbai65 | 2001 | 520 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 7.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Deo et al, Sindhudurg66 | 2006 | - | - | - | - | 1022 | 20+ | K+ F+ PG | 9.3 | |

US, Urine sugar; RBG, random blood glucose; K, known diabetes; F, fasting blood glucose; PG, post glucose load

| Region | Urban | Rural | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Place | Year of publication | n | Age (yr) | Method adopted for diagnosis | Prevalence (%) | n | Age (yr) | Method adopted for diagnosis | Prevalence (%) |

| Ahuja7 (Urban + Rural) | Ahmedabad | 3496 | 3.7 | 3483 | 1.9 | |||||

| Kolkata | 3488 | 1.8 | 3515 | 1.5 | ||||||

| Cuttack | 1979 | 3849 | 15+ | K + PG* | 2.0 | 2993 | 15+ | K + PG* | 1.6 | |

| Delhi | 2358 | 0.9 | 2308 | 1.5 | ||||||

| Pune | 2796 | 1.9 | 2818 | 1.1 | ||||||

| Trivandrum | 3090 | 1.8 | - | - | ||||||

| Ahuja8 (Urban + Rural) | Delhi | 2572 | 4.1 | 992 | 1.5 | |||||

| Kalpa | 999 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Trivandrum | 1991 | 20+ | K + PG* | 1488 | 20+ | K + PG* | 1.3 | |||

| Kolkata | 2375 | 0.8 | ||||||||

| Ahmedabad | 1294 | 3.9 | ||||||||

| Ramachandran et al9 (only Metros) | Delhi | 2300 | K + F+ PG* | 11.6 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Bangalore | 1359 | 12.4 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Chennai | 2001 | 1668 | 20+ | K+ PG* | 13.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| Hyderabad | 1427 | 16.6 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Kolkata | 2378 | 11.7 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Mumbai | 2084 | K +F+ PG* | 9.3 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Sadikot et al10 (Metros excluded) | National | 2004 | 10617 | 25+ | K +F+ PG* | 5.9 | 7746 | 25+ | K +F+ PG* | 2.7 |

| Ajay et al67 (Industrial cohort) | Delhi | 3358 | 10.9 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Hyderabad | 908 | 14.1 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Chennai | 2008 | 492 | 20+ | K +F+ PG* | 10.4 | - | - | - | - | |

| Bangalore | 702 | 10.7 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Trivandrum | 1098 | 16.6 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Mohan et al11 (Urban + Rural) | Ballabgarh | 4.8 | 1.1 | |||||||

| Chennai | 2008 | 15230 | 15 - 64 | K | 8.7 | 13522 | 15 - 64 | K | 3.9 | |

| Delhi | 10.3 | - | ||||||||

| Dibrugarh | 5.5 | 0.6 | ||||||||

| Nagpur | 3.2 | 0.6 | ||||||||

| Trivandrum | 11.2 | 9.6 | ||||||||

US, Urine sugar; RBG, random blood glucose; K, known diabetes; F, fasting blood glucose; PG, post glucose load

Scarcity of good quality epidemiological data is a serious limitation in developing countries like India. So far, the major source of population level estimates of diabetes in India has been ad hoc surveys in limited geographical regions. Table III gives the various limitations of existing studies of diabetes prevalence in India. Starting from the early 1960s, there have been over 60 studies (Table I & Table II) which have reported on the prevalence of diabetes in India. These studies are characterized by several limitations: regional, with small sample sizes, low response rates, use varied diagnostic criteria and sample designs, lack standardization, leading to measurement errors and incomplete reporting of results. To date, surveys have not managed to capture standardized measures of diet and physical activity, health service utilization, health care costs and the level of glycaemic control. In addition, a disproportionately large number of studies have examined the prevalence of diabetes in urban settings, to the exclusion of the rural population, where over 70 per cent of India’s population resides.

| (1) | Ad hoc surveys |

| (2) | Regional focus |

| (3) | Lack of uniform methodology |

| (4) | Small sample sizes |

| (5) | Rural representation inadequate |

| (6) | Incomplete diagnostic work |

| (7) | Use of varied diagnostic criteria |

| (8) | Use of varied sample designs |

| (9) | Inadequate coverages |

| (10) | Lack of standardization |

| (11) | Measurement errors |

| (12) | Done in different time periods |

Thus, as is evident, there is not a single study which has looked at all the States and regions of India and none that has included urban and rural areas in addition to metropolitan cities. Indeed, as noted earlier, there is no study which looked at the prevalence of diabetes even in a representative sample of a single State of the country.

Diabetes-related complications

Till the early 1990s, there were no population-based data on diabetes-related complications. Such data are of great significance since these represent the burden of the disease. Clinic-based data are subject to referral bias and only represent the profile of patients seen in that particular clinic. Table IV presents the studies on the prevalence of diabetes-related complications in India69–92. These studies have reported interesting differences in the patterns of complications seen in Asian Indians. For example, the prevalence of retinopathy73, nephropathy80, and peripheral vascular disease, appear to be lower92, while that of neuropathy appears to be similar to prevalence rates reported in the West84. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease on the other hand was shown to be higher90 than that reported in the West.

| Author | Year | Clinic/population based study | City/State | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinopathy: | ||||

| Rema et al69 | 1996 | Clinic | Chennai | 34.1 |

| Ramachandran et al70 | 1999 | Clinic | Chennai | 23.7 |

| Dandona et al71 | 1999 | Population | Hyderabad | 22.6 |

| Narendran et al72 | 2002 | Population | Palakkad | 26.8 |

| Rema et al73 | 2005 | Population | Chennai | 17.6 |

| Nephropathy: | ||||

| John et al74 | 1991 | Clinic | Vellore | Microalbuminuria: 19.7 |

| Diabetic nephropathy: 8.9 | ||||

| Gupta et al75 | 1991 | Clinic | New Delhi | Microalbuminuria: 26.6 |

| Yajnik et al76 | 1992 | Clinic | Pune | Microalbuminuria: 23.0 |

| Vijay et al77 | 1994 | Clinic | Chennai | Proteinuria: 18.7 |

| Mohan et al78 | 2000 | Clinic | Chennai | Macroproteinuria with retinopathy: 6.9 |

| Varghese et al79 | 2001 | Clinic | Chennai | Microalbuminuria: 36.3 |

| Unnikrishnan et al80 | 2006 | Population | Chennai | Microalbuminuria : 26.9 |

| Overt nephropathy with diabetic retinopathy : 2.2 | ||||

| Neuropathy: | ||||

| Ramachandran et al70 | 1999 | Clinic | Chennai | 27.5 |

| Ashok et al81 | 2002 | Clinic | Chennai | 19.1 |

| Viswanathan V et al82 | 2005 | Clinic | Chennai | 17 |

| Viswanathan V et al82 | 2005 | Clinic | Vellore | 16 |

| Viswanathan V et al82 | 2005 | Clinic | Delhi | 9 |

| Viswanathan V et al82 | 2005 | Clinic | Madurai | 14 |

| Chanda et al83 | 2006 | Clinic | Bangalore | 64.1 |

| Pradeepa et al84 | 2008 | Population | Chennai | 26.1 |

| Coronary artery disease: | ||||

| Chaddha et al85 | 1990 | Population | New Delhi | 9.7 |

| Raman Kutty et al86 | 1993 | Population | Kerala | 7.4 |

| Mohan et al87 | 1995 | Clinic | Chennai | 17.8 |

| Gupta et al88 | 1995 | Population | Uttar Pradesh | 7.9 |

| Ramachandran et al89 | 1998 | Population | Chennai | 14.3 |

| Ramachandran et al70 | 1999 | Clinic | Chennai | 11.4 |

| Mohan et al90 | 2001 | Population | Chennai | 21.4 |

| Gupta et al91 | 2002 | Population | Rajasthan | 8.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease: | ||||

| Premalatha et al92 | 2000 | Population | Chennai | 6.3 |

Diabetes is traditionally known as a “silent disease,” exhibiting no symptoms until it progresses to severe target organ damage93. Case detection, therefore, requires active and opportunistic screening efforts94. However, even where diagnosed, inadequate glycaemic control95–97 results in seriously disabling or life-threatening complications. As a result, diabetes is the leading cause of adult-onset blindness and kidney failure worldwide and is responsible for approximately 6 per cent of total global mortality, accounting for 3.8 million deaths in 20079899. Although South Asia currently has the highest number of diabetes-related deaths, accurate prevalence estimates of complications in large segments of the population are glaringly absent.

Rationale for a national diabetes survey

India is a vast, heterogeneous country with an approximate population of 1.1 billion people, a complex socio-political history, immense diversity of culture, dialects and customs, public and privately-funded health infrastructure, and competing demands on human and structural resources. These factors together negate a single policy solution for the whole country and this underscores the importance of generating a robust, representative base of evidence that documents burdens of disease, identifies vulnerable populations and draws attention to disease determinants100101. Approximately 742 million people in India live in rural areas102103 where awareness of chronic diseases is extremely low104 and the ratio of unknown-to-known diabetes is 3:1 (compared to 1:1 in urban areas)11. Crude estimates suggest that type 2 diabetes prevalence in rural areas is much lower (approximately 25-50%) than in urban areas105106, although trend data are now suggesting that diabetes prevalence in rural areas is rapidly catching up with the urban estimates. In addition, given that the overwhelming majority of India’s population lives in rural areas and that there is a higher ratio of undiagnosed cases, the burden of diabetes and NCDs may be much greater in rural areas. Also, large disparities in human and infrastructural resource allocation between rural and urban areas are directly related to divergence in disease outcomes107108. Therefore, the Government of India’s National Rural Health Mission will benefit greatly from more precise estimates of diabetes and NCD burden in all States of India. The gist of the rationale for a national diabetes survey in India is given in Table V.

| (1) | Rapid rise in the prevalence of diabetes in India. |

| (2) | Younger age of onset of diabetes in India leading to great economic and social burden. |

| (3) | Existing studies have limitations. |

| (4) | No study which is representative of even a whole State and thus no representative national figures. |

| (5) | Marked heterogeneity between States which limits the generalisability of results of small regional studies. |

| (6) | Multi-centre studies are also limited to either metros or small towns and villages and do not take into account all the geographical divisions. |

| (7) | Population based work on diabetes complications is sparse with no single study looking at all the complications in different regions of India. |

| (8) | To estimate the current burden of diabetes (as a model of NCDs) and its complications in India. |

| (9) | Need for such data to plan and develop national health policies. |

Significance and impact of a large representative national study

Given that there is a growing epidemic of diabetes in India109, reliable and informative epidemiological evidence is vital to quantify impacts and predictors of disease and facilitate formulation of prevention and control strategies. Effective prevention and care models have the potential to lower rates of target organ damage, disability and premature mortality, resulting in long term savings in health expenditure110111. Currently, there are large data deficits regarding the distribution, trends, determinants and disease outcomes and where information is available, vast State-wise heterogeneity and variable quality limit its value.

A national study on diabetes called as the ICMR-INDIA DIABETES (ICMR-INDIAB) study is being planned which will address the following questions (i) What is the prevalence of diabetes in India?, (ii) What is the urban prevalence and what is the rural prevalence?, (iii) Are there really regional disparities in the prevalence of diabetes in India? and (iv) If so, are these differences due to differing dietary patterns (rice vs. wheat as staple food), or differences in levels of physical activity, or are there true ethnic differences in the susceptibility to diabetes even within the Asian Indian population? These are just some of the questions that will be answered by this large national study on diabetes.

A well-planned national study on diabetes like the ICMR-INDIAB study could provide a truly representative picture of diabetes in the whole nation. Such a study would provide reliable nationwide data, not only on prevalence of diabetes, but also on pre-diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. It can also be used to generate appropriate thresholds for serum lipid parameters for the country’s population. It could provide information on dietary patterns and physical activity for India as a whole, in addition to studying the genetic diversity of India in relation to NCDs in general, and diabetes in particular. This kind of data will be extremely informative and contribute to national and State level policy decision making. An additional component of the study would be to provide accurate data on all diabetes complications and this would once again be the first of its kind in the country. Even in rural areas, where literacy rates are low, the study would provide information about health and disease. In addition, training young investigators and personnel from the local areas could empower them with knowledge and technical skills which can be used for the betterment of the community as a whole. Further, enduring analyses and sub-analyses from a study of this magnitude will fuel the evolution of more research questions, including the potential to repeat measures to examine future trends. Fig. 2 presents a flow chart depicting the study pathway.

- Flow chart to depict the study path.

The challenges involved in doing a large national study are many - geographic barriers, social barriers, language barriers, cultural barriers and ethnic barriers are just to name a few. However, the major challenge will be to maintain the highest standards of quality to produce world class data.

In conclusion, despite recent advances in knowledge, the prevention and control of non communicable diseases like diabetes and CVD remain a major challenge in India112113. Several important questions regarding the regional distribution, determinants, and interventions for diabetes remain unanswered. Thus the need for a large multi-State representative population-based study on the prevalence of diabetes and its complications and related metabolic NCDs like hypertension, obesity, dyslipidaemia and cardiovascular disease in India cannot be emphasized.

References

- Diabetes in adults is now a Third World problem.The WHO Ad Hoc Diabetes Reporting Group. Bull World Health Organ. 1991;69:643-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. In: Gan D, ed. Diabetes atlas (4th ed). International Diabetes Federation. Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2009. p. :1-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of known diabetes in Indians in New Delhi and London. J Med Assos Thai. 1987;70:54-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abdominal obesity, visceral fat and Type 2 diabetes - “Asian Indian Phenotype”. In: Mohan V, Gundu HR, Rao, eds. Type 2 diabetes in South Asians: Epidemiology, risk factors and prevention. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers; 2006. p. :138-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic syndrome – Emerging clusters of the Indian Phenotype. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:445-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological studies on diabetes mellitus in India. In: Ahuja MMS, ed. Epidemiology of diabetes in developing countries. New Delhi: Interprint; 1979. p. :29-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent contributions to the epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in India. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 1991;11:5-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in India: National Urban Diabetes Survey. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1094-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in India using the WHO 1999 criteria: prevalence of diabetes in India study (PODIS) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;66:301-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urban rural differences in prevalence of self-reported diabetes in India - the WHO-ICMR Indian NCD risk factor surveillance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;80:159-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Report 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005.

- The burden of mortality attributable to diabetes: realistic estimates for the year 2000. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2130-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-communicable diseases in low and middle income countries: a priority or a distraction? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:961-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Burden of non-communicable diseases in South Asia: evidence for epidemic of coronary heart disease in India is weak. BMJ. 2004;328:1499.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconsidering the history of type 2 diabetes in India: emerging or re-emerging disease? Natl Med J India. 2008;21:288-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a north Indian town. Indian J Med Res. 1966;54:1025-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological study of diabetes in the town of Varanasi. Diabetes in the town of Varanasi. In: Patel JC, Talwalker NG, eds. Diabetes in the tropics. Bombay: Diabetic Association of India; 1966. p. :76-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological study of diabetes mellitus in defence population in Lucknow Cantonment. J Indian Med Assoc. 1973;61:23-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of known diabetes mellitus in an urban Indian environment: the Darya Ganji diabetes survey. Br Med J. 1986;293:423-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiologic survey of diabetes mellitus in and around Rewa. In: Diabetes Res Clin Pract. Vol 5. 1988. p. :S 634.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and risk factors in a rural Punjab population: prevalence and correlation with various risk factors. Indian Heart J. 1994;46:319-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in the Kashmir Valley of the Indian subcontinent. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;47:135-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia in urban slum population in northern India. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose and insulin resistance syndrome in an urban Indian population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61:69-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of multiple coronary risk factors in Punjabi Bhatia community: Jaipur Heart Watch-3. Indian Heart J. 2004;56:646-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Diabetes in Camel-Milk Consuming‘RAICA’ Rural Community of North-West Rajasthan. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 2004;24:109-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular risk factor prevalence among men in a large industry of northern India. Natl Med J India. 2005;18:59-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trends in prevalence of coronary risk factors in an urban Indian population: Jaipur Heart Watch-4. Indian Heart J. 2007;59:346-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetes in a rural area of central India. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 2007;27:8-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zero prevalence of diabetes in camel milk consuming Raica community of north-west Rajasthan, India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76:290-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of diabetes in Hyderabad. In: Patel JC, Talwalker NG, eds. Diabetes in the tropics. Bombay: Diabetic Association of India; 1966. p. :68-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- prevalence of diabetes in Madras. In: Patel JC, Talwalker NG, eds. Diabetes in the tropics. Bombay: Diabetic Association of India; 1966. p. :29-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey of diabetes mellitus in Pondicherry. In: Patel JC, Talwalker NG, eds. Diabetes in the tropics. Bombay: Diabetic Association of India; 1966. p. :33.

- [Google Scholar]

- A survey of diabetes mellitus in rural population of India. Diabetes. 1972;21:1192-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey for detection of hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus in Tenali. In: Bajaj JS, ed. Diabetes mellitus in developing countries. New Delhi: Interprint; 1984. p. :55.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of diabetes in an urban population in South India. Br Med J. 1988;297:587-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of diabetes in Asians of the Indian subcontinent. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1990;6:125-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of glucose intolerance in Asian Indians.Urban-rural difference and significance of upper body adiposity. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:1348-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes mellitus in a rural population in south India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;24:47-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rising prevalence of NIDDM in an urban population in India. Diabetologia. 1997;40:232-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and incidence of type-2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in a selected Indian urban population. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:1060-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Type 2 diabetes in southern Kerala: variation in prevalence among geographic divisions within a region. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:287-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- High risk for coronary heart disease in Thiruvananthapuram city: a study of serum lipids and other risk factors. Indian Heart J. 2000;52:29-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of known diabetes in Chennai City. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;49:974-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS No. 4). Intra-urban differences in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in southern India - the Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS No. 4) Diabet Med. 2001;18:280-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secular trends in the prevalence of diabetes and glucose tolerance in urban South India-the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-17) Diabetologia. 2006;49:1175-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence and management of diabetes in rural India. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1717-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of known and undetected diabetes and associated risk factors in central Kerala - ADEPS. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;74:289-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors associated with urbanization in India. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:893-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survey for detection of glycosuria, hyperglycaemia and diabetes mellitus in urban and rural areas of Cuttack district. J Assoc Physicians India. 1971;19:681-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological study of diabetes mellitus in West Bengal. J Diabetic Assoc India. 1975;15:97-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of type 2 diabetes in urban population in north-eastern. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 1998;18:97-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Manipur. In: Shah SK, ed. Diabetes update. Guwahati, India: North Eastern Diabetes Society; 2001. p. :13-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in a selected population with special reference to influence of family history and anthropometric measurements-the Kolkata policeman study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:841-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A sample survey to determine the incidence of diabetes in Bombay. Indian Med Assoc. 1963;41:448-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- The K.E.M. Hospital Group: incidence of diabetes. In: Patel JC, Talwalker NG, eds. Diabetes in the tropics. Bombay: Diabetic Association of India; 1966. p. :1-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hypertension and diabetes mellitus in a rural village. J Diabetic Assoc India. 1986;26:68-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes mellitus in Dombivli- an urban population study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:713-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- To identify the risk factors for high prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in Indian rural population. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 2006;26:19-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of diabetes mellitus in the Indian industrial population. Diabetes Med. 2008;25:1187-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes India.The burden of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in India using the ADA1997 criteria: prevalence of diabetes in India study (PODIS) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;66:293-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of retinopathy in non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in southern India. Diabetes Res Clin Practice. 1996;24:29-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of vascular complications and their risk factors in type 2 diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 1999;47:1152-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population based assessment of diabetic retinopathy in an urban population in southern India. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:937-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetic retinopathy among self reported diabetics in southern India: a population based assessment. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1014-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy in Urban India: The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) Eye Study- I. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2328-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in non insulin dependant diabetes mellitus. Indian J Med Res. 1991;94:24-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of microalbuminuria in diabetes: a study from north India. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1991;12:125-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary albumin excretion rate (AER) in newly-diagnosed type 2 Indian diabetic patients is associated with central obesity and hyperglycaemia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1992;17:55-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of proteinuria in non-insulin dependent diabetes. J Assoc Physicians India. 1994;42:792-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of proteinuria in Type 2 diabetes mellitus seen at a diabetes centre in Southern India. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:569-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of microalbuminuria in Type 2 diabetes mellitus at a diabetes centre in southern India. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:399-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic nephropathy in an urban south Indian population: The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES - 45) Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2019-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of neuropathy in type 2 diabetic patients attending a diabetes centre in south India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:546-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Profile of diabetic foot complications and its associated complications - a multicentric study from India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005;53:933-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perception of foot problems among diabetic patients: A cross sectional study. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 2006;26:77-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic neuropathy in an urban south Indian population: the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-55) Diabet Med. 2008;25:407-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological study of coronary heart disease in urban population of Delhi. Indian J Med Res. 1990;92:424-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of coronary heart disease in the rural population of Thiruvananthapuram district, Kerala, India. Int J Cardiol. 1993;39:59-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ischaemic heart disease in south Indian NIDDM patients – A clinic based study on 6597 NIDDM patients. Int J Diab Developing Countries. 1995;15:64-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meta-analysis of coronary heart disease prevalence in India. Indian Heart J. 1996;48:241-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in urban Asian Indians. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:967-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of coronary artery disease and its relationship to lipids in a selected population in South India - The Chennai Urban population Study (CUPS No.5) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:682-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of coronary heart disease and risk factors in an urban Indian population: Jaipur Heart Watch-2. Indian Heart J. 2002;54:59-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and risk factors of peripheral vascular disease in a selected South Indian population.The Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS) Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1295-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of retinopathy at diagnosis among Type 2 diabetic patients attending a diabetic centre in South India. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1058-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current concepts in screening for noncommunicable disease: World Health Organization Consultation Group Report on methodology of noncommunicable disease screening. J Med Screen. 2005;12:12-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of diabetes care in the middle- and high-income group populace: the Delhi Diabetes Community (DEDICOM) survey. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2341-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diab Care Asia-India Study: diabetes care in India - current status. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:717-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges in diabetes care in India: sheer numbers, lack of awareness and inadequate control. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:443-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic Intelligence Unit. In: The silent epidemic: An economic study of diabetes in developed and developing countries. New York: The Economist Intelligence Unit; 2007.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. The human, social & economic impact of diabetes. Available from: http://www.idf.org/home/index.cfm?node=41, accessed on February 2, 2009

- [Google Scholar]

- What does social justice require for the public’s health.Public health ethics and policy imperatives? Health Affairs. 2006;25:1053-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Improving the Quality of Care in Developing Countries.”. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills AA, Musgrove P, eds. Disease control priorities in developing countries (2nd ed). New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. :1293-307.

- [Google Scholar]

- Census of India. Rural-Urban Distribution. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/India_at_glance/rural.aspx, accessed on May 21, 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- Health Education to Villages. Rural - Urban distribution of population. Available from: http://hetv.org/india/population-2001.htm, accessed on May 21, 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- Education and income: double-edged swords in the epidemiologic transition of cardiovascular disease. Ethn Dis. 2003;13((2 Suppl 2)):S158-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- DiabetesIndia.com. The Indian Task Force on Diabetes Care in India. Available from: http://www.diabetesindia.com/diabetes/itfdci.htm, accessed on May 21, 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- Migration and its impact on adiposity and type 2 diabetes. Nutrition. 2007;23:696-708.

- [Google Scholar]

- Socio-economic burden of diabetes in India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2007;55((Suppl)):9-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global Diabetes Landscape - Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in South Asia: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Control. Insulin. 2008;3:78-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:679-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of cardiovascular disease in high-risk individuals in low-income and middle-income countries: health effects and costs. Lancet. 2007;370:2054-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- The global impact of noncommunicable diseases: estimates and projections. World Health Stat Q. 1988;41:255-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reducing the growing burden of cardiovascular disease in the developing world. Health Affairs. 2007;26:13-24.

- [Google Scholar]