Translate this page into:

Subinhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin targets quorum sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing inhibition of biofilm formation & reduction of virulence

Reprint requests: Dr Kusum Harjai, Department of Microbiology, BMS Block, Panjab University, Chandigarh 160 014, Punjab, India e-mail: kusum_harjai@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Biofilms formed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa lead to persistent infections. Use of antibiotics for the treatment of biofilm induced infection poses a threat towards development of resistance. Therefore, the research is directed towards exploring the property of antibiotics which may alter the virulence of an organism besides altering its growth. The aim of this study was to evaluate the role of subinhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin (CIP) in inhibiting biofilm formation and virulence of P. aeruginosa.

Methods:

Antibiofilm potential of subinhibitory concentration of CIP was evaluated in terms of log reduction, biofilm forming capacity and coverslip assay. P. aeruginosa isolates (grown in the presence and absence of sub-MIC of CIP) were also evaluated for inhibition in motility, virulence factor production and quorum sensing (QS) signal production.

Results:

Sub-minimum inhibitory concentration (sub-MIC) of CIP significantly reduced the motility of P. aeruginosa stand and strain and clinical isolates and affected biofilm forming capacity. Production of protease, elastase, siderophore, alginate, and rhamnolipid was also significantly reduced by CIP.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Reduction in virulence factors and biofilm formation was due to inhibition of QS mechanism which was indicated by reduced production of QS signal molecules by P. aeruginosa in presence of subinhibitory concentration of CIP.

Keywords

Biofilm

ciprofloxacin

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

quorum sensing

virulence factors

Extensive use of antibiotics for the treatment of infections has led to the development of drug resistance in various pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Therefore, several antibiotics are being explored for their efficacy in inhibiting virulence of pathogens since sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of antibiotics broadly affect the patterns of transcription in bacteria and may function as signaling mediators rather than function by targeting growth of microbes1. Some antibiotics in concentration below the MIC for the organism also affect the synthesis of extracellular virulence factors which are regulated by quorum sensing signal molecules (QSSMs)2. Production of some of the exoenzymes may be downregulated or upregulated in the presence of antibiotics3. Antibiotics such as erythromycin, azithromycin (AZM), clindamycin, etc. are known to inhibit virulence traits of various pathogens45. Subinhibitory concentration of erythromycin reduces exoenzyme production by P. aeruginosa in vitro1. These studies point towards the potential of antibiotics in attenuating virulence of a pathogen, other than their bactericidal effect, which may be more beneficial in the course of treatment.

Capability of P. aeruginosa to form biofilms adds to difficulties in eradicating its infection with the help of antibiotics. Resistance of biofilm towards component of host immune system as well as antimicrobial agents is associated with persistent infections in medical settings. Acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) based small diffusible signal molecules participate in regulatory network and controls biofilm formation and production of several extracellular virulence factors1. Sub-MICs of macrolides and clindamycin have been shown to suppress biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa through inhibition of alginic acid and exopolysaccharide6. AZM at subinhibitory concentrations inhibits motility and biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa7. Although ciprofloxacin (CIP) lowers the levels of protease and exotoxin A8, little is known about the efficacy of CIP in inhibiting biofilms of P. aeruginosa. The present study was designed to evaluate the effect of CIP on biofilm forming capacity of P. aeruginosa. For this purpose sub-MIC of CIP was selected and its effect on motility and biofilm formation along with virulence factor production by five selected strains of P. aeruginosa was studied.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted in the Microbiology department of Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. Standard strain PAO1 and clinical isolates (n=4, CLI-4) of P. aeruginosa were used. These clinical isolates, obtained from Government Medical Hospital and College, Chandigarh, were maintained in our laboratory. The study protocol was approved by the Panjab University Ethical Committee. Bioreporter strain Escherichia coli MG4 carrying plasmid pkDT17 was used to quantify the AHL molecules produced by P. aeruginosa.

MIC determination: The MIC of CIP (Hi-Media Laboratories, Mumbai) was determined according to Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)guidelines9 against the standard P. aeruginosa strain PAO1. Briefly, from stock solutions of CIP (10 mg/ml), different dilutions of 0.1 µg/ml-20 mg/ml were prepared. A 6 h culture was used as the inoculum. The concentration of antibiotic resulting in no visible growth was taken as the MIC. For all further experiments, a sub-MIC of CIP was selected by plotting the growth curve. P. aeruginosa strain PAO1was grown in presence and absence of different concentrations (¾, ½, ¼) of sub-MIC of CIP. Samples were withdrawn at specific time intervals and absorbance was read at 600 nm.

Motility assays: Swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities (in mm) were assayed on agar plates containing specific medium10.

Swimming motility - Plates containing 1 per cent tryptone, 0.5 per cent NaCl and 0·3 per cent agarose (all from Hi-Media, Mumbai) were prepared and were point inoculated from an overnight Luria-Bertani (LB) broth culture. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h and motility was assayed as the radius of the circular expansion of bacterial growth from the point of inoculation (in mm).

Swarming motility - Plates of nutrient agar containing bacteriological agar (0.5% w/v) and glucose (5g/l) (all from Hi-Media, Mumbai) were prepared. Plates were allowed to dry at room temperature. Cells were point inoculated from overnight culture and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Twitching motility - The overnight culture was stabbed through agar of LB plates (Hi-Media) (1% agar) to the bottom of the Petri dish and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. After removal of agar, attached cells were stained with crystal violet (1% w/v) and the radius of growth expansion was determined.

Biofilm-forming capacity: Biofilm-forming capacity was determined by a microtitre plate assay, as described by Wagner et al11. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm and biofilm-forming capacity was calculated as A570 in the presence and absence of CIP. A control without antibiotic was run simultaneously.

Biofilm generation: Sterile Foley catheter pieces (Rusch) of 1 cm were cut and a biofilm was allowed to develop under static conditions for 7 days as described previously12 in the presence or absence of a sub-MIC of CIP. The catheter pieces were transferred to fresh medium every 24 h. Each day, the catheter pieces in duplicate were removed, rinsed three times with PBS and cells were removed from the surface by scraping with a sterile scalpel blade. The cells were sonicated using a low-level sonication cycle and vortexed for 30 sec. Dispersed samples were centrifuged and the biofilm cells were suspended in one ml PBS. Serial dilutions were prepared and plated on MacConkey agar plates.

Coverslip assay: Coverslip assay was performed using modified protocol as described by Merritt et al13. Sterile coverslips were transferred to LB flask seeded with culture. Biofilm was allowed to develop under static conditions for seven days in the presence or absence of a sub-MIC of CIP. The coverslips were transferred to fresh medium every 24 h. Each day, the coverslips in duplicate were removed, rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained with crystal violet stain for 15 min. Excessive stain was removed by rinsing with PBS. Coverlips were then visualized under light microscope.

Test supernatant and cells: Cultures were grown in Luria broth at 37°C for 16-18 h. After incubation, cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 15 min. Cell free supernatants and cell pellets were separated and used in various experiments.

Protease production: Proteolytic activity was estimated according to the method of Visca et al14. Briefly, 0.5 ml of culture supernatant was diluted in 10mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) and incubated with 15mg hide powder azure (Sigma Chemicals, USA) at 37°C for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm and results were expressed in units per liter (U/l).

Elastase activity: For elastase activity 15 mg of substrate (elastin-congo red; Sigma Chemicals, USA) was suspended in 1 ml of culture supernatant mixed with 1 ml of 100 mM tris-succinate buffer (pH 7.0) supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2. Tubes were kept at 37°C for 2 h under shaking conditions. Reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml of 0.7 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) and was centrifuged at 4000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Absorbance was taken at 495 nm and results were expressed in units per liter (U/l)14.

Pyochelin estimation: For quantitation of pyochelin one ml cell-free supernatant, one ml each of 0.5 N HCl, nitrite molybdate reagent and 1N NaOH were mixed and the final volume was made to 5 ml with distilled water. Absorbance was taken at 510 nm15.

Rhamnolipid estimation: Rhamnolipid was quantified by Orcinol method16. Briefly, strains were grown overnight in chemically defined medium and culture supernatant was extracted with diethyl ether; 100 μl of this extract was diluted with 1:10 in freshly prepared orcinol reagent [7.5 volume of 60% H2SO4 and 1 volume of 1.6% (w/v) orcinol in distilled water] and mixture was heated in water bath at 80°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 421 nm. L-Rhamnose (Sigma chemicals, USA) was used to standardize the assay.

Haemolysis estimation: Both cell free and cell bound haemolysin was estimated following the method of Linkish and Vogt17. For cell bound haemolysins 1.5 ml of 2 per cent human RBCs (red blood cells) suspension was mixed with 1.5 ml of biofilm cells and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Mixture was centrifuged at 8000 g for 15 min. Supernatant was collected and absorbance was read at 545 nm. The amount of haemolysin (mg/ml) was calculated by using lyophilized haemoglobin as reference. For cell free haemolysins 1.5 ml of 2 per cent human RBCs suspension was mixed with 1.5 ml of cell free supernatant and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Assay mixture was centrifuged at 5000 g for 5 min and absorbance was taken at 545 nm.

Alginate estimation: Alginate was quantified by carbazol method18. Briefly, alginate was extracted from culture supernatant using 2 per cent cetyl pyridium chloride and propanol; 30 μl of this was diluted with one ml of freshly prepared 10 mM borate reagent. To this, 30 μl of 1 per cent carbazol reagent was added. Mixture was heated at 55°C for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 500 nm. The amount of alginate was calculated by using pure alginate (Sigma, USA) as reference.

Bioassay of AHL production: The level of AHLs in bacterial culture supernatants was quantified by using reporter strain E. coli MG4 as described previously19. Briefly, an overnight culture of E. coli MG4 in Luria Bertani broth was diluted in the same medium to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm and stored on ice. Each bioassay tube contained two ml of reporter strain cell suspension and 0.5 ml of test supernatant. The mixtures were incubated at 30°C in a water bath for 5 h with rotation at 100 rpm. The β-galactosidase activity was then measured1920.

Statistical analysis: All experiments were repeated three times to validate the reproducibility of experiments. Results were analysed statistically by Student's t test using SPSS 11.05 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

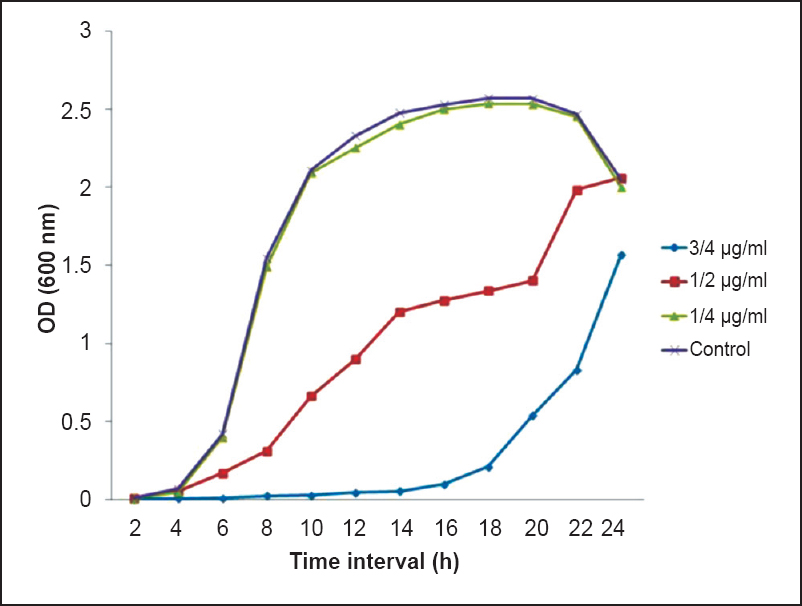

Selection of sub-MIC of CIP: MIC of CIP against P. aeruginosa was found to be 0.25 µg/ml. To select the sub-MIC of ciprofloxacin a growth curve was plotted using different concentrations of CIP (¾ of MIC, ½ of MIC and ¼ of MIC). Sub-MIC of 0.06 µg/ml (¼ of MIC) was selected for further study since it had negligible effect on the growth of P. aeruginosa in comparison to control (Fig. 1).

- Growth profile of P. aeruginosa grown in presence and absence of subinhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin (CIP) (¾, ½, and ¼ of MIC).

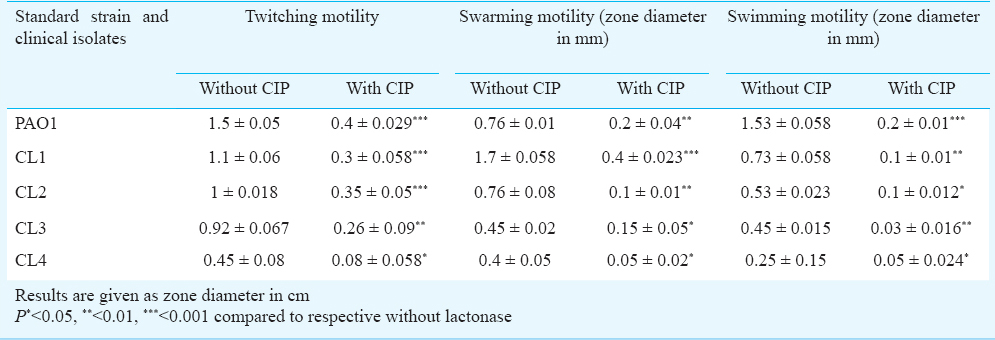

Effect of CIP on motility: To observe the effect of CIP on biofilm formation, it was imperative to see the effect of CIP on the swimming, swarming and twitching motilities of P. aeruginosa. All clinical isolates and standard strain were grown overnight in the absence of CIP and then inoculated onto motility plates with sub-MIC of CIP. It was observed that the presence of CIP significantly reduced all three types of motilities (Table I, Fig. 2).

- Demonstration of the twitching (a, b), swimming (c-e) and swarming (f-h) motility of P. aeruginosa standard strain PAO1 and clinical isolates in absence and presence of sub-MIC of CIP.

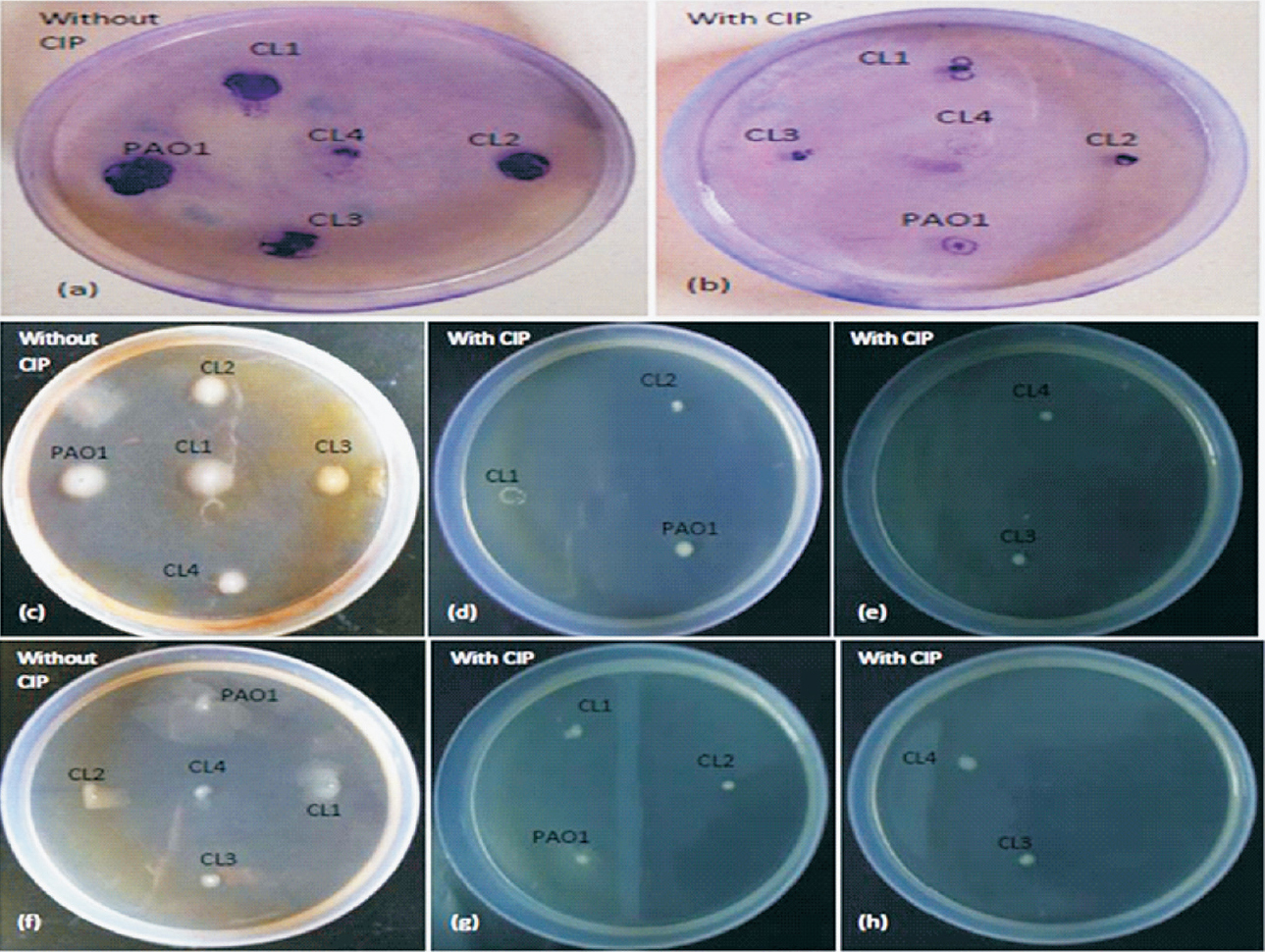

Effect of CIP on biofilm formation: To evaluate the efficacy of CIP on biofilm formation the biofilm-forming capacity (BFC) of PAO1, CL1, CL2, CL3 and CL4 was calculated. Results demonstrated that CIP significantly (P<0.01) reduced biofilm-forming capacity of all the isolates Fig. 3. Effect of CIP was also determined on different days of biofilm formation by quantifying log (cfu/ml) values. Biofilm was generated on Foley catheters for seven successive days in the absence and presence of CIP. Standard strain PAO1 showed an increase in the log count of biofilm cells from day 1 with a maximum peak value on day 4 (10.5±0.7), and further decline upto day 7 Table II. The peak on day 4 was indicative of maximum accumulation of bacterial cells on the surface of the catheter. In the presence of CIP, a significant reduction in the log cfu of biofilms was observed (7.5±0.5) on day 4. The clinical isolates CL1, CL2, CL3 and CL4 also showed a similar trend with a peak on day 4 and a reduction in biofilm formation over 7 days in presence of CIP.

- Biofilm-forming capacity estimated by a crystal violet assay of P. aeruginosa standard strain PAO1 and clinical isolates in the absence or presence of a sub-MIC of CIP. A standard reference value of 1 was taken as the control (no CIP) for each isolate. The results are presented as means±SD obtained from three independent experiments.*, P<0.01, compared to control.

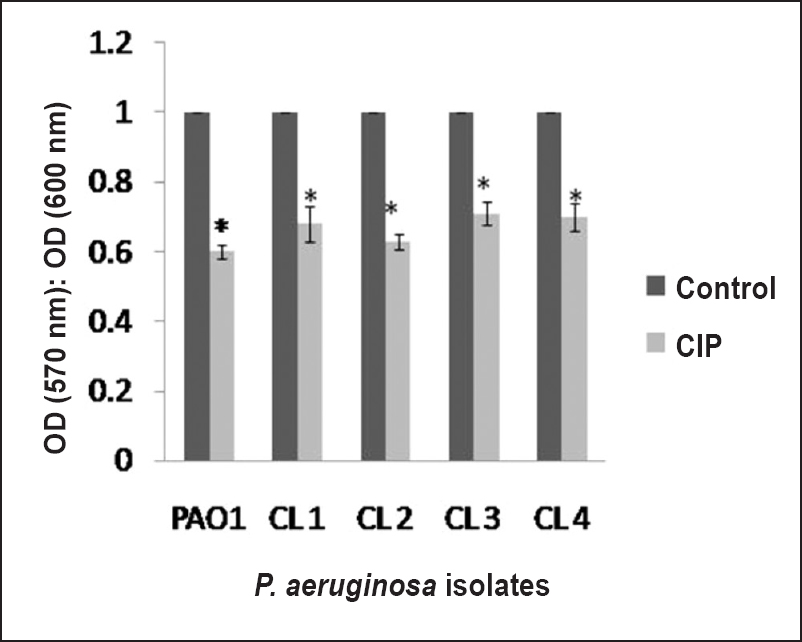

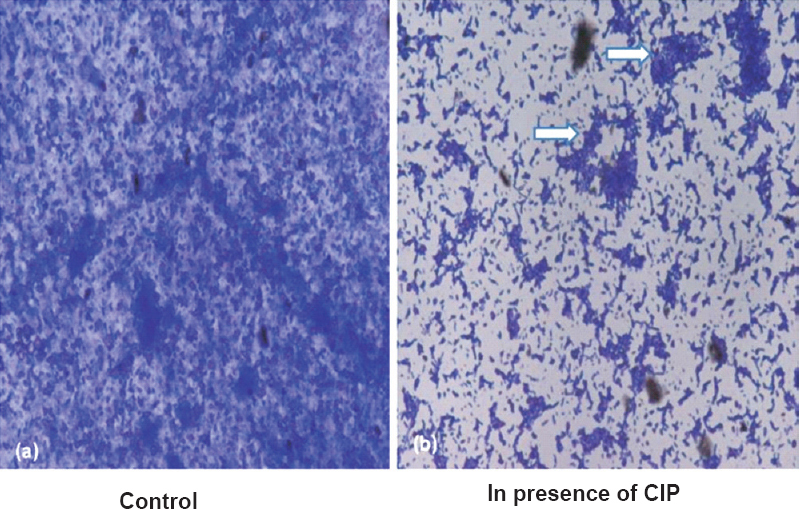

CIP inhibited biofilm formation on coverslips: To visualize the biofilm inhibition exhibited by CIP, P. aeruginosa isolates were allowed to form biofilms on sterile coverslips. Light microscopic observation of coverslips after crystal violet staining showed that CIP inhibited biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa in comparison to control (Fig. 4).

- Representative photomicrograph (450 X) showing biofilm formed by P. aeruginosa on coveslip in presence (b) and absence of (a) sub-MIC of CIP. Arrows show chunks of biofilm observed in presence of CIP.

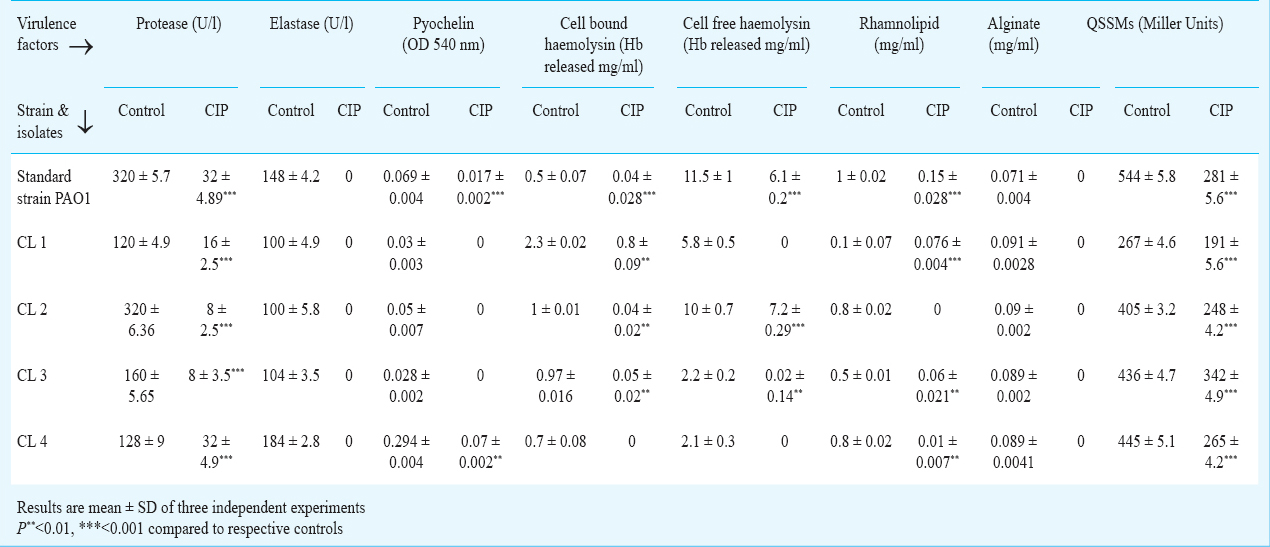

CIP inhibited virulence factor production by P. aeruginosa: The effect of CIP on production of protease, elastase, rhamnolipid, alginate and siderophore was studied. It was observed that CIP significantly reduced the production of all the virulence factors. It completely inhibited production of elastase and alginate by the standard strain and all clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. pyochelin production was completely inhibited in three clinical isolates (Table III). High level of reduction in haemolysin production (cell free and cell bound) was observed when the isolates were grown in the presence of CIP. Protease production was reduced in standard strain (32 U/l) showing a 10-fold decrease while in clinical isolates protease production was reduced to 16, 8, 8 and 32 U/l in comparison to their respective controls (120, 320, 160, 128 U/l). Similarly, all clinical isolates and standard strain showed significant decrease in rhamnolipid production when grown in presence of CIP.

Inhibition of QSSMs production by P. aeruginosa in presence of CIP: CIP reduced QSSMs production to 281 Miller Units indicating approximately 50 per cent decrease in comparison to control (544 Miller units) in standard strain PAO1, whereas in clinical isolates, QSSMs production was reduced to 191, 248, 342 and 265 Miller units in comparison to their respective controls (267, 405, 436 and 445 Miller units) (Table III).

Discussion

Pathogens devise newer strategies like formation of biofilms for their survival in vitro as well as in vivo. Increasing resistance towards antibiotics open a wide area of research for discovery of therapeutic agents which can target the virulence of pathogens instead of targeting their growth. Some antibiotics in addition to their bactericidal effect can affect synthesis of certain protein at concentration below MIC resulting in altered gene expression hence affecting the physiology of micro-organism. Subinhibitory concentration of macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin, clindamycin, AZM have also been shown to attenuate the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa by inhibiting biofilm formation and virulence2. CIP is known to have high bactericidal activity and therapeutic efficacy against P. aeruginosa and is a drug of choice against many Gram-negative pathogens21. CIP was selected since it is also active against P. aeruginosa in a low metabolically active state21. The present study was designed to see whether CIP, a fluoroquinolone, known for its antibacterial properties and low biofilm penetration, possess property to inhibit biofilm and decrease virulence of an organism at subinhibitory concentrations as seen with other macrolide antibiotics.

Swimming, swarming and twitching motilities of P. aeruginosa mediated by flagella and type IV pili1022, help in bringing the cells in close proximity of the surface. Type IV pili enable the organism to migrate across biotic surfaces, recruit cells from adjacent monolayers and form cell aggregates23. Macrolide antibiotic, AZM, also showed inhibiting effect on swimming, swarming and twitching motility27. Since motile subpopulation in biofilms form the cap of mushroom like structure and also help in spread of biofilms24, altered motility of P. aeruginosa in presence of CIP may attenuate the biofilms and also affect its architecture and dispersal. Permeability and penetration of antibiotics through extracellular polymeric substance is expected to increase in such biofilms25. CIP was found to attenuate the virulence of biofilms of P. aeruginosa by altering their secretion of protease when exposed to bactericidal concentration of this antibiotic3. It was also observed that 1/8th of MIC of CIP had negligible effect on viability of cells within biofilms3. However, in the present study it was observed that CIP at sub-MIC concentrations induced significant decrease in motility and biofilm formation leading to its inhibition on day 7. Similarly, Balaji et al25 observed concentration dependent inhibitory effect of fluoroquinolone antibiotics on biofilms of Streptococcus pyogenes. Hoffmann et al27 have suggested that impairment in the ability of P. aeruginosa to form fully polymerized alginate biofilms may help in attenuating its virulence.

Elaborating virulence factors is an important feature of a pathogen. P. aeruginosa produces a battery of virulence traits namely protease, elastase, rhamnolipid, alginate and siderophore. These factors ensure survival of P. aeruginosa in host and induce damage. Subinhibitory concentrations of macrolides are known to attenuate the virulence of P. aeruginosa. All these factors are known to modulate immune response by inducing rapid necrotic killing of polymorphonuclear leucocytes28 and are prime cause of inducing inflammation in vivo. In the present study, subinhibitory concentration of CIP resulted in reduction in production of these factors. This may help in reducing the damage caused by inflammatory agents to host tissue. Despite causing damage, factors like rhamnolipid and alginate also play important role in maintaining the architecture of biofilms24. Reduced levels of rhamnolipid and alginate observed may have contributed to development of less structured biofilms. CIP also significantly inhibited biofilm formation resulting in less structured biofilms which later can become more permeable to the treatment27.

Since all these factors are known to be under the regulation of QS system, effect of CIP on production of QS signal molecule by P. aeruginosa was also studied. CIP induced approximately 1.5 fold decrease in QSSM production by all the isolates and standard strain of P. aeruginosa in comparison to control. More than 300 genes of P. aeruginosa are known to be regulated by QS29. Skindersoe et al29 in their study showed that sub-MIC of CIP downregulated 49 per cent of QS regulated genes thereby causing a major change in gene expression. These results indicated that observed decrease in biofilm formation and virulence factor production was due to inhibition of QSSM production by sub-MIC of CIP. Reduction in production of these molecules in presence of CIP not only attenuates the virulence but may also reduce the inflammation induced by these signal molecules in vivo since QSSMs themselves act as virulence factors and participate in inflammation and modulate immune response30.

In conclusion, the present study showed that CIP at subinhibitory concentration inhibited biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa thereby attenuating its pathogenicity. Reduction in production of virulence factors renders the organism defenseless which may allow superior action of immune response and bactericidal agents against P. aeruginosa. The mechanism behind biofilm inhibition and reduction in virulence was found to be inhibition of QSSMs. CIP, like a macrolide AZM, was efficient in attenuating the virulence of P. aeruginosa. It may provide basis for further studies targeted to investigate potency of other antibiotics as QS inhibitors.

Acknowledgment

The first author (PG) acknowledges University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, for providing SRF.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:17025-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quorum-sensing antagonistic activities of azithromycin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1: a global approach. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1680-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Secretion of proteases by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms exposed to ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3281-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence factors by subinhibitory concentrations of azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:681-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of clindamycin on growth and haemolysin production by Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12(Suppl C):105-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of azithromycin on the biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro. Chemotherapy. 1996;42:186-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by azithromycin and its effectiveness in urinary tract infections. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:300-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Interference of ciprofloxacin with the expression pathogenicity factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Adam D, Hahn H, Opferkuch W, eds. The influence of antibiotics on the host-Parasite relationships II. Springer-Verlag: Berlin Heidelberg; 1985. p. :246-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 18th Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2008.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inorganic polyphosphate is needed for swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4885-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the hierarchy of quorum-sensing regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:469-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of macrophage secretory products on elaboration of virulence factors by planktonic and biofilm cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;29:12-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growing and analyzing static biofilms. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2005(Chapter 1) Unit 1B

- [Google Scholar]

- Metal regulation of siderophore synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and functional effects of siderophore-metal complexes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2886-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Calorimetric determination of the components of 3, 4 dihydroxyphenylalanine tyrosine mixture. J Biol Chem. 1937;118:531-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrocarbon assimilation and biosurfactant production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4212-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direct hemolysin activity of phospholipase-A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;270:241-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology. 1999;145:1349-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa with lasI quorum-sensing deficiency during corneal infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1897-903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ciprofloxacin in polyethylene glycol-coated liposomes: efficacy models of acute or chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2575-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5990-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiation and distribution of colistin and sodium dodecyl sulfate-tolerant cells in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:28-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of subinhibitory concentrations of fluoroquinolones on biofilm production by clinical isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:963-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effect of fosfomycin and fluoroquinolones against Pseudomonas aeruginosa growing in a biofilm. Acta Med Okayama. 2005;59:209-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Azithromycin blocks quorum sensing and alginate polymer formation and increases the sensitivity to serum and stationary-growth-phase killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and attenuates chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in Cftr2/2 mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3677-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid necrotic killing of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is caused by quorum-sensing-controlled production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2007;153:1329-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of antibiotics on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3648-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential immune modulatory activity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing signal molecules. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6463-70.

- [Google Scholar]