Translate this page into:

Stem cells survive oncotherapy & can regenerate non-functional gonads: A paradigm shift for oncofertility

For correspondence: Dr Deepa Bhartiya, Stem Cell Biology Department, ICMR-National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health, Jehangir Merwanji Street, Parel, Mumbai 400 012, Maharashtra, India e-mail: bhartiyad@nirrh.res.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A large proportion of patients who survive cancer are rendered infertile as an unwanted side effect of oncotherapy. Currently accepted approaches for fertility preservation involve banking eggs/sperm/embryos or ovarian/testicular tissue before oncotherapy for future use. Such approaches are invasive, expensive, technically challenging and depend on assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Establishing a gonadal tissue bank (for cancer patients) is also fraught with ethical, legal and safety issues. Most importantly, patients who find it difficult to meet expenses towards cancer treatment will find it difficult to meet expenses towards gonadal tissue banking and ART to achieve parenthood later on. In this review an alternative strategy to regenerate non-functional gonads in cancer survivors by targeting endogenous stem cells that survive oncotherapy is discussed. A novel population of pluripotent stem cells termed very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs), developmentally equivalent to late migratory primordial germ cells, exists in adult gonads and survives oncotherapy due to their quiescent nature. However, the stem-cell niche gets compromised by oncotherapy. Transplanting niche cells (Sertoli or mesenchymal cells) can regenerate the non-functional gonads. This approach is safe, has resulted in the birth of fertile offspring in mice and could restore gonadal function early in life to support proper growth and later serve as a source of gametes. This newly emerging understanding on stem cells biology can obviate the need to bank gonadal tissue and fertility may also be restored in existing cancer survivors who were earlier deprived of gonadal tissue banking before oncotherapy.

Keywords

Cancer

cryopreservation

fertility

gametes

ovary

stem cells

testis

transplantation

VSELs

An Introduction to oncofertility

Oncofertility is a term coined by Teressa K. Woodruff from Northwestern University, Chicago, USA in 2006 which actually combines oncology with reproductive research to expand available options for cancer patients to preserve fertility to ensure biological parenthood later on in life (http://oncofertility.northwestern.edu/about-oncofertility-consortium). With advances in cancer treatment, survival rates in cancer patients have increased; however, infertility is one of the unwanted side effects of the treatment. A large fraction of cancer survivors are children and young adolescents. An international society named International Society for Fertility Preservation (ISFP) is active in this field (http://www.isfp-fertility.org/) and Teressa Woodruff's group has also established the Oncofertility Consortium at NW University, Chicago, USA (http://oncofertility.northwestern.edu/about-oncofertility-consortium). ISFP is governed by a board of 18 Directors from America, Europe and Asia and has recently teamed up with American Society for Reproductive Medicine and European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology to further advance the field. This development and the current status and future perspectives in the field were recently reviewed1. Because of excessive load of cancer patients, counselling patients regarding fertility options before oncotherapy is not streamlined in many parts of the world. However, awareness has increased, and Fertility Preservation Society of India (www.fpsind.com) has also been established2.

In 2016, Fournier3 discussed rights of cancer patients for oncofertility. Patient information describing fertility issues and cancer treatment was provided4. The role of oncologists to take care of fertility of cancer patients5 and legal issues associated with cryopreserved embryos6 were discussed. Bhartiya7 pointed out that by targeting endogenous very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) to restore fertility for cancer patients, one could avoid legal, ethical and safety issues associated with oncofertility. Gracia and Woodruff8 responded to the concept of VSELs to tackle oncofertility issues and looked forward to ongoing research in the field. The aim of the present article was to provide an update on VSELs research and how these endogenous stem cells in adult ovary and testis could be targeted to restore fertility of cancer survivors.

Available options for fertility preservation before oncotherapy

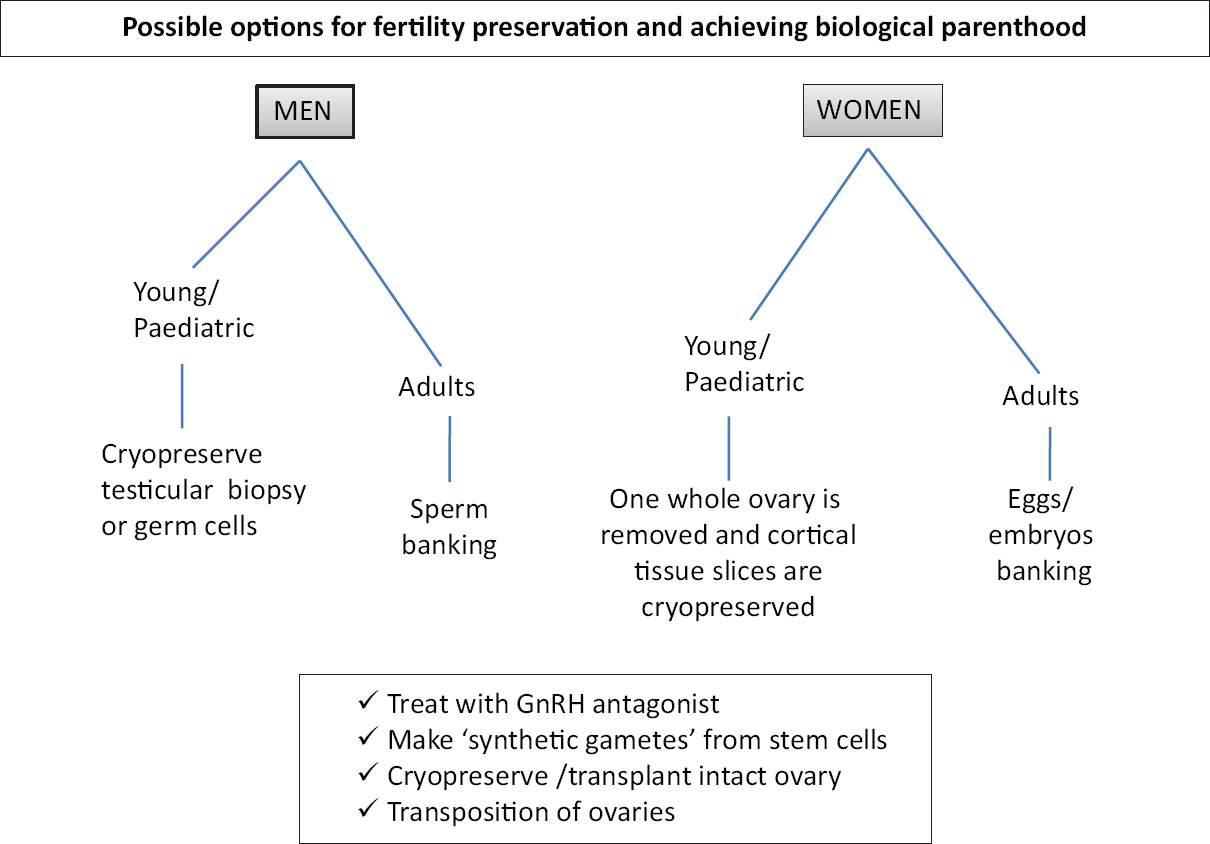

Most important is the option to make ‘artificial gametes’ from embryonic and/or induced pluripotent [(ES)/iPS] stem cells. Other sex-specific available options for fertility preservation are discussed below and listed in Fig. 1.

- Possible options of fertility preservation for cancer patients before oncotherapy.

Males: The best option for males to preserve their fertility is sperm cryopreservation. If cryopreserved properly, sperm survive and remain viable for more than a decade and can be used for intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) to achieve biological parenthood. However, young boys who cannot produce semen samples are counselled for the preservation of testicular biopsies. The biopsies could be cryopreserved as such or germ cells are isolated and cryopreserved. The cryopreserved cells could later be used to either three-dimensional (3D) culture of tubular tissue to obtain sperm, germ cells differentiation into sperm in vitro or for the intra-tubular transplantation of germ cells in the azoospermic tubules9.

Females: Female cancer patients can possibly be subjected to ovarian stimulation, and eggs/embryos can be cryopreserved before oncotherapy. However, this option becomes unavailable at times when oncotherapy cannot be delayed and also when the cancer is hormone sensitive. In such cases and in young girls, where oocytes/embryos cannot be preserved, a whole ovary is removed, and cortical tissue slices are cryopreserved as a source of large numbers of primordial and primary follicles for future use. Attempts are also being made to generate ‘artificial ovary’ and 3D/2D culture to mature primordial follicles in vitro10.

Current worldwide usage of available options to restore fertility in cancer survivors

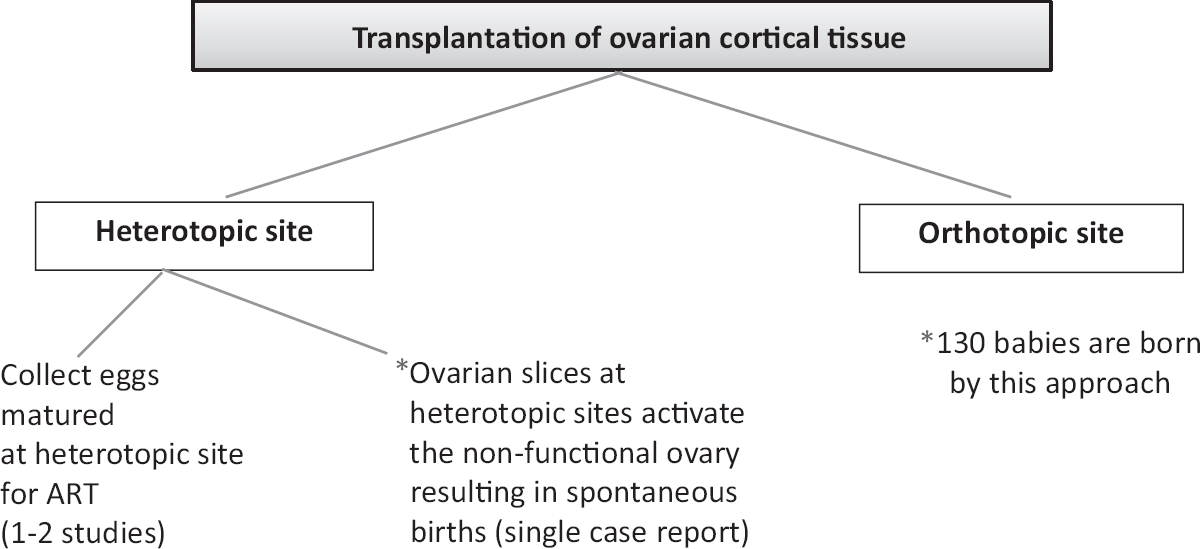

Infertility clinics offer facilities such as sperm; oocyte/embryos cryopreservation and cancer patients are referred to in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics to avail such facilities. Ovarian cortical tissue transplantation (OCT) has resulted in remarkable success; 130 live births have been reported worldwide after transplanting frozen-thawed ovarian cortical tissue slices on the surface of the non-functional ovary11, however the procedure is still considered experimental1213. Donnez et al14 were the first group to combine ovarian tissue cryopreservation and orthotopic transplantation resulting in a live birth, and this is considered as a landmark in the history of human reproductive medicine. Basically, OCT involves transplantation of ovarian cortical tissue slices at either orthotopic or heterotopic sites. Fig. 2 shows a comparison of the two approaches. Babies were born after orthotopic transplantation of the ovarian tissue whereas birth of babies after heterotopic transplantation was rare. Kristensen et al15 reported live birth after heterotopic OCT followed by IVF. Other options to restore fertility include making gametes from stem cells, whole ovary transplantation, maturation of follicles in 2D/3D culture and use of testicular tissue to restore spermatogenesis. An update on these varied approaches and current status are available in recent reviews161718192021.

- Various strategies to transplant cryopreserved ovarian slices and their outcome. *The transplanted cortical tissue could act as a source of growth factors/cytokines to the non-functional ovary resulting in its regeneration

Making ‘artificial gametes’ using ES/iPS cells is still in the research phase. Success was recently achieved to derive mouse gametes and birth of pups22. However, the process (rate of pregnancy outcome) remained low and fraught with safety issues possibly due to inappropriate epigenetic reprogramming2223. Deriving human gametes from ES/iPS stem cells is a long way to reach the clinics24. The following issues need to be resolved (i) hES cells need to be derived by somatic cell nuclear transfer for providing biological parenthood, (ii) iPS cells have inherent drawbacks including high chances that they may harbour genomic as well as mitochondrial mutations and also at times they may remain partially reprogrammed and retain the epigenetic marks of the somatic cells from which they are derived, (iii) methods need to be evolved to convert hES/iPS cells into primordial germ cells-like cells (PGCLCs) since PGCs are natural precursors for gametes, and (iv) hES cells are in a ‘primed’ state and need to be converted to ‘naïve’ state to improve differentiation into gametes. This may expand their differentiation/regenerative ability171825262728.

Our research efforts have led to the identification of a novel population of pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues termed very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) in the gonads. VSELs are developmentally equivalent to late migratory PGCs, are quiescent in nature, survive oncotherapy, spontaneously differentiate into gametes and can be targeted to regenerate the ablated, non-functional gonads29.

An introduction to pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues (VSELs)

Pluripotent stem cells including human ES cells derived from inner cell mass of blastocyst stage embryo30 and embryonic germ (EG) cells derived from PGCs31 were reported in 1998. Being equivalent to PGCs, VSELs are pluripotent and yet relatively mature compared to the human ES cells and closer to human EG cells. Similar to EG cells which do not divide readily in vitro, neither form teratomas but form spheres readily3132, VSELs do not divide in culture and have been reviewed333435.

After having worked on human ES cells for more than a decade, we have now shifted gears on VSELs as these possibly have better regenerative potential36. These stem cells have been labelled differently by various investigators and have remained elusive over decades due to their small size and presence in very few numbers37. VSELs are the most primitive, pluripotent stem cells in the adult organs and give rise to tissue-specific stem cells by undergoing rare asymmetrical cell divisions to self-renew and give rise to slightly bigger tissue-committed adult stem cells ‘progenitors’38. The tissue committed adult stem cells or ‘progenitors’ in turn undergo symmetrical cell divisions, clonal expansion and further differentiation into tissue-specific cell types.

Being developmentally equivalent to the late migratory PGCs, VSELs express pluripotent and also PGCs-specific markers. Scaldaferri et al39 have reported hematopoietic activity in putative mouse PGCs that were also found to co-express several markers of hematopoietic precursors. Virant-Klun40 have described VSELs representing a potential developmental link between germinal lineage and haematopoiesis. Being pluripotent, VSELs have euchromatin and show biallelic expression of various imprinted genes including IGF2 and H19. H19 expression is high due to biallelic expression and IGF2 is not expressed - resulting in their quiescent nature4142. Ratajczak et al34 have been successful to achieve expansion of VSELs in vitro by treating them with valproic acid and nicotinamide. Another group could expand them in vitro by treating with a small molecule pyrimidoindole derivative (UM171) in a feeder-free condition while retaining their pluripotent state43. Tripathi et al44 reported increased expression of pluripotent markers in peripheral blood on treating with a highly active nano-formulation of resveratrol. Ratajczak's group45 reported these stem cells in mouse bone marrow for the first time in 2006 and showed their ability to differentiate into three germ layers. Havens et al46 reported that human cord blood VSELs had the ability to differentiate into three germ layers. Our group has also shown differentiation of mouse bone marrow VSELs into three germ layers, hematopoietic stem cells and male germ cells on providing proper cues47 and Monti et al48 reported the presence of pluripotent VSELs in human cord blood using a novel strategy and also their ability to differentiate into three germ layers.

VSELs in mammalian testis

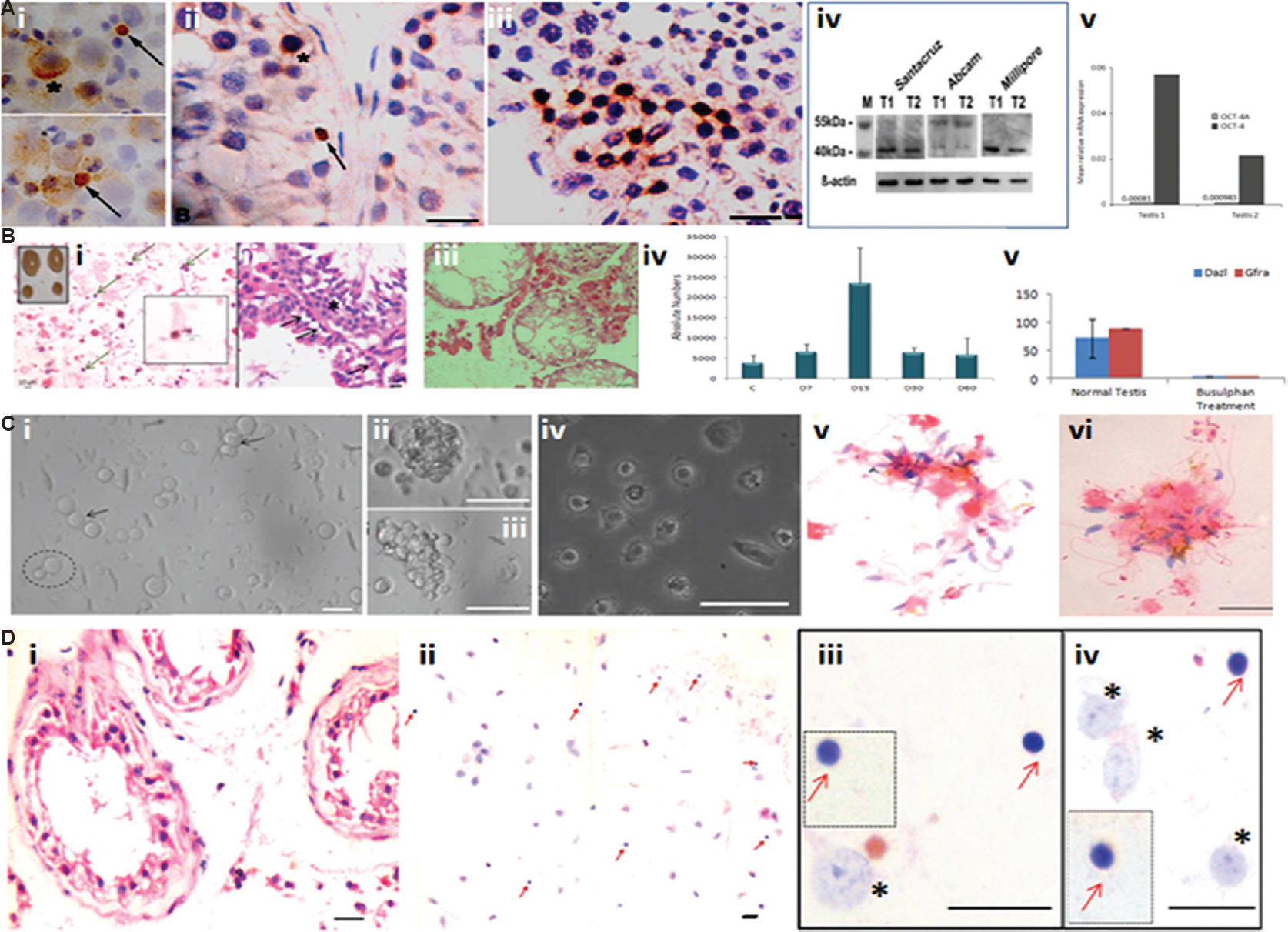

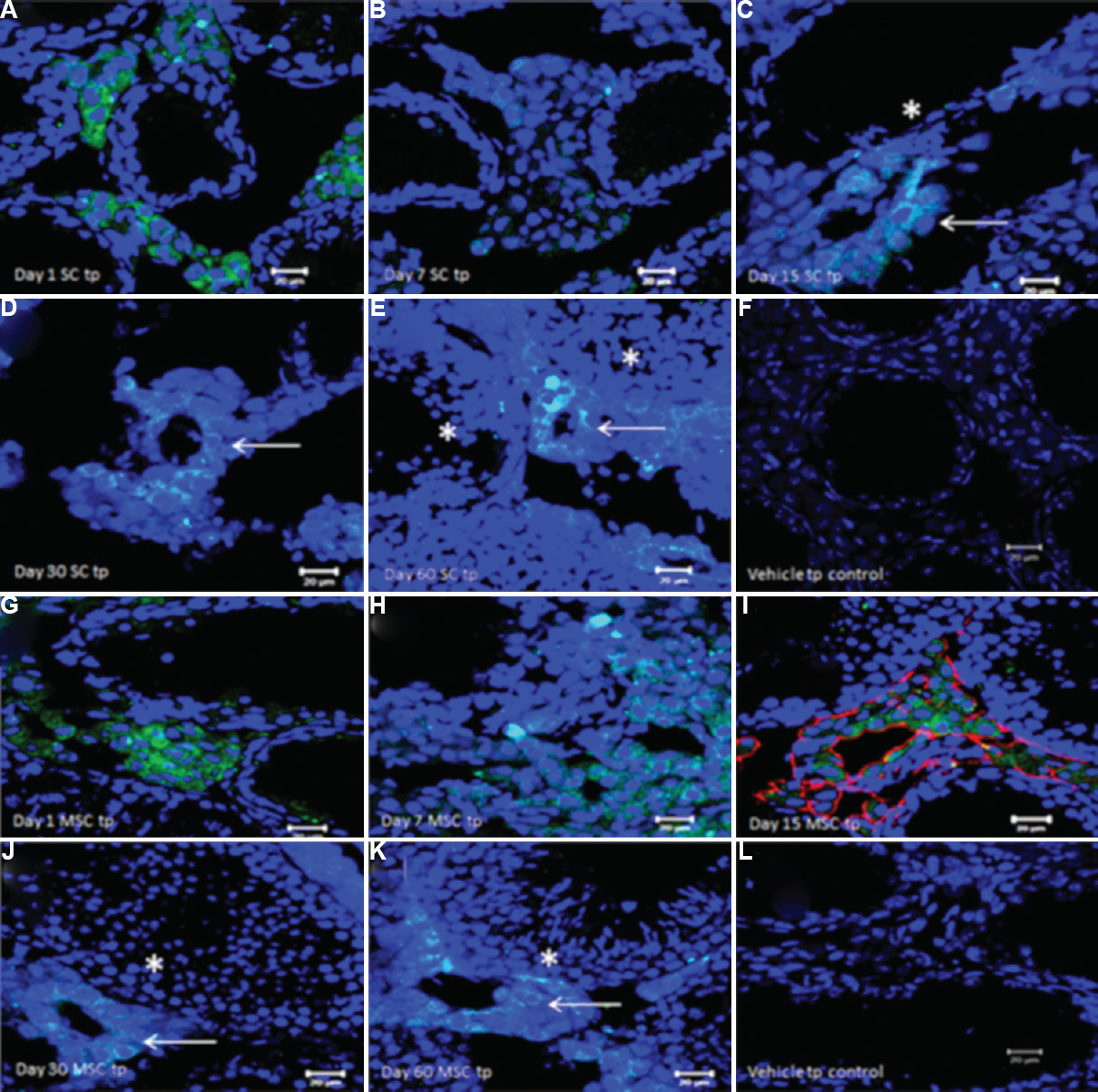

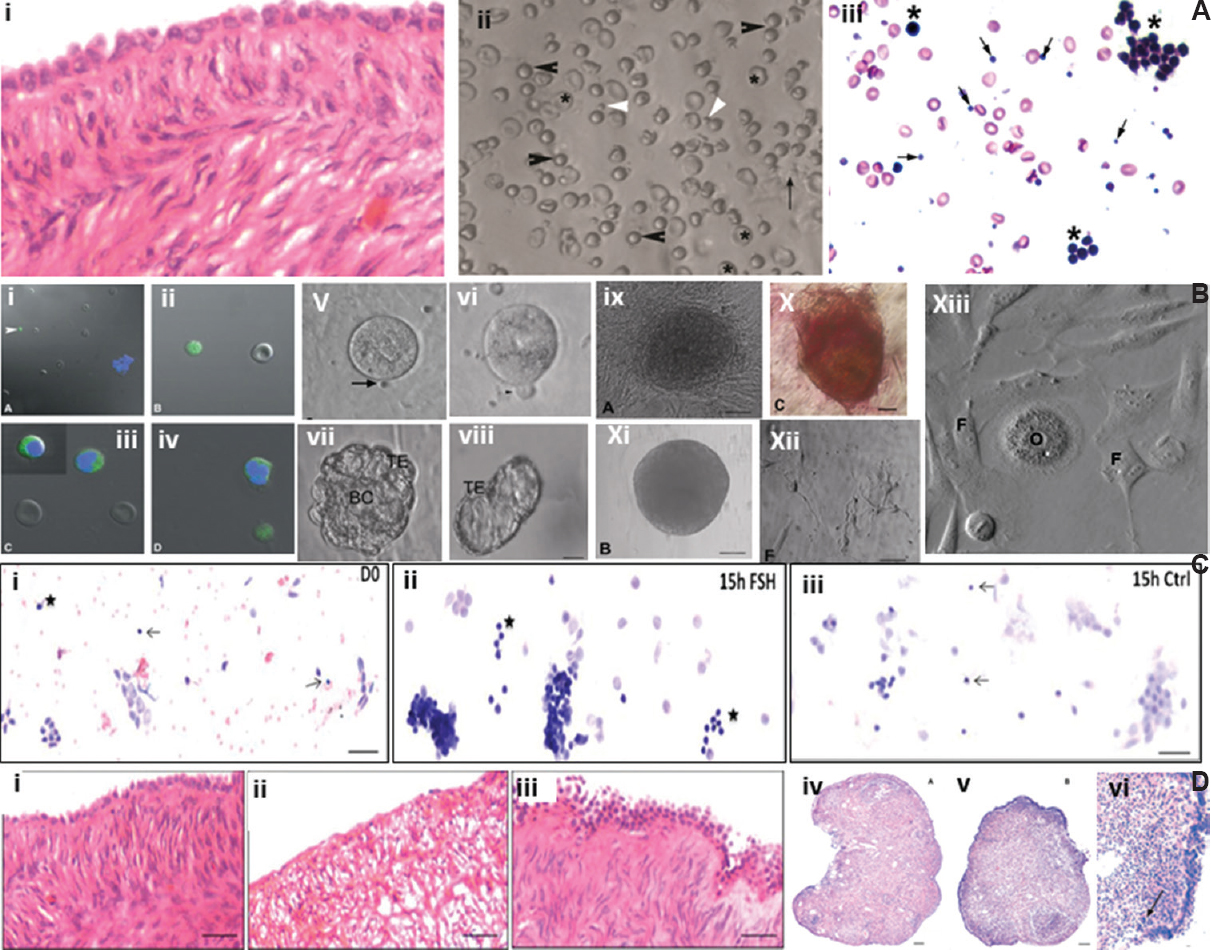

The studies on testicular VSELs (Fig. 3) and effect of transplanting niche cells (sertoli or mesenchymal cells) to restore spermatogenesis in chemoablated mouse testis (Fig. 4) are discussed in details below. Immuno-localization studies of OCT-4 led to the identification of VSELs in addition to spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs) in the human testes49 (Fig. 3A). Three different antibodies were used for OCT-4 immuno-expression on testicular cell smears, sections and by Western blotting. Specific primers/probes were designed to evaluate two distinct isoforms of OCT-4 by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization studies. The two isoforms of OCT-4 include OCT-4A (nuclear expression and specific to pluripotent state of a stem cell) and OCT-4B (cytoplasmic expression and possibly represents differentiated state of the stem cells). Our findings suggested the presence of small-sized VSELs expressing nuclear OCT-4A and slightly bigger SSCs with cytoplasmic OCT-4B. Results suggested that VSELs were the most primitive stem cells that differentiated into SSCs in the testis. VSELs were found in very few numbers whereas the cells expressing cytoplasmic OCT-4B were in abundance. Later, we studied these stem cells in mouse testis (Fig. 3B) and the following results have emerged: (i) VSELs survive busulfan treatment (25 mg/kg) in mouse testis. They initially increased in numbers on day 15 after busulfan treatment and later could be detected on day 30 whereas germ cells/sperm were lost after chemoablation5051. (ii) Testicular VSELs were found to express receptors for follicle-stimulating hormone (FSHR) including both alternatively spliced isoforms FSHR1 and FSHR354. VSELs in chemoablated mouse testis increased in numbers after FSH treatment and this action was possibly mediated through FSHR3. (iii) VSELs were found to undergo self-renewal and asymmetric cell division and considered the most primitive stem cells in the testis3854. Thus, the most primitive stem cells in the testes55 that undergo self-renewal and give rise to SSCs might be VSELs. (iv) Microarray studies on Sertoli cells (niche cells for testicular stem cells) isolated from normal and chemoablated testis showed marked changes in the transcriptome after busulfan treatment51 suggesting that although stem cells survive, their niche gets compromised by chemotherapy. (v) Transplanting healthy niche cells including Sertoli cells from syngeneic mice or bone marrow mesenchymal cells through inter-tubular route could regenerate chemoablated testis51. Spermatogenesis was restored from the VSELs that survived chemotherapy when paracrine support was provided by the transplanted healthy niche cells (Sertoli or mesenchymal stromal cells) (Fig. 4). This was further discussed in depth56. (vi) Chemoablated testicular tubules collected on day 60 after busulfan treatment when cultured on a Sertoli cells bed and in the presence of Sertoli cells conditioned medium and FSH revealed that the surviving stem cells spontaneously differentiated into sperm in vitro52 (Fig. 3C).

- Testicular stem cells, effect of oncotherapy and in vitro culture. (A) Nuclear octamer-binding transcription-4 (OCT-4) expressing small-sized spherical stem cells (SSCs) (arrow) exist along with slightly bigger cells with cytoplasmic OCT-4 (asterix) in (i) testicular cell smears, and (ii) testicular sections, (iii) the bigger sized SSCs undergo clonal expansion implying rapid cell division with incomplete cytokinesis, (iv) testicular tissue was studied for OCT-4 expression by Western blotting using three different commercial antibodies. Santa Cruz and Millipore antibodies were specific to OCT-4A whereas Abcam antibody detected both alternatively spliced isoforms OCT-4A and B. (v) relative expression of Oct-4A and Oct-4B (alternately spliced isoforms of OCT-4 of which OCT-4A is alone responsible for pluripotent state whereas OCT-4B is suggestive of cells entering differentiation) was studied by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for relative mRNA expression normalized to 18S RNA. As evident, Oct-4A is very less compared to OCT-4 (Oct-4A and B). T1 and T2 are two different testicular tissue samples obtained from men undergoing orchidectomy to manage prostate cancer. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 49. (B) (i) Effect of busulfan treatment (25 mg/kg) on mouse testis. Inset shows the effect of treatment on testes which appear to shrink in size and reduce in weight by 4 wk after chemoablation; H&E stained cell smear on day 15 after treatment shows presence of small sized spherical putative stem cells (<5 μm) with high nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio marked by arrows, (ii) testis sections prepared on day 15 after busulfan treatment show the presence of small spherical stem cells along the basement membrane of the seminiferous tubules marked by arrows, (iii) by day 30, the seminiferous tubules get devoid of germ cells, (iv) flow cytometry data enumerating absolute number of VSELs on different days after busulfan treatment show that initially, the number of VSELs increases on day 15 and later reduce but they do survive till day 30. (v) Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for germ cell markers - Dazl and Gfra shows marked reduction of these transcripts on day 30 in agreement with histological data shown in (iii). Source: Reproduced with permission from Refs 5051. (C) In vitro culture of cells isolated from chemoablated seminiferous tubules. (i) Testicular stem cells that survive chemotherapy remain non-adherent and semi-attached on top of a feeder made by the Sertoli cells that get attached to the culture surface. The smaller VSEL divide and give rise to a slightly bigger SSC (broken circle) whereas the SSC divides rapidly and forms chains (arrow), and (ii & iii) clusters. These cells undergo differentiation to form (iv) spermatids, and (v & vi) sperm. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 52. (D) Azoospermic human testicular biopsies of cancer survivors of childhood cancer harbour stem cells. (i) H&E stained testicular sections show azoospermia and complete lack of germ cells, (ii) testicular smears show presence of small, spherical putative stem cells, (iii & iv) higher magnification of smears showing Sertoli cells (*) and VSELs (red arrow) that survive oncotherapy in seminiferous tubules. VSELs are spherical in shape with minimal cytoplasm whereas Sertoli cells are characterized by a large nucleus with prominent nucleoli. Insets include VSELs captured from different microscopic fields. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 53.

- Fate of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive Sertoli/mesenchymal cells on transplantation in chemoablated mice testis, studied by immuno-expression of GFP on cryosections. (A and B) GFP+ve Sertoli cells were observed in the interstitium on days 1 and 7 after transplantation, (C) on day 15, GFP+ve cells start to align as neo-tubule-like structures (arrow) in the vicinity of germ cells depleted ‘native’ tubules (*), (D and E) the neo-tubules are retained through days 30 and 60 after transplantation (arrows). Note resumption of spermatogenesis in ‘native’ non-GFP tubules (*) on day 60. (F) No GFP staining in is detected in busulfan-treated controls corresponding to day 30. (G and H) GFP+ve mesenchymal cells were detected in the interstitium on days 1 and 7 after transplantation, (I) GFP+ve cells aligned themselves as neotubule-like structures by day 15 and also colocalized vimentin (red staining) confirming their mesenchymal nature, (J and K) On day 30 and 60 GFP+ve neo-tubules (arrows) were clearly visualized in the vicinity of native tubules showing spermatogenesis (*). (L) No GFP expression was observed in busulfan-treated controls corresponding to day 30. Neo-tubules formed after transplantation of both Sertoli and mesenchymal stromal cells do not differentiate into sperm and only provide paracrine support to the stem cells in the native tubules that survived chemotherapy and undergo spermatogenesis. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 51.

These results were intriguing since ES/iPS cells require very sophisticated in vitro system with sequential addition of hormones and growth factors for their induction into gametes. The main reason for our success was because VSELs are developmentally equivalent to PGCs which are also natural precursors to gametes. We further isolated bone marrow VSELs and cultured in a manner similar to that described above. Male germ cells were detected in culture after 14 days47. Shirazi et al57 purified stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 (SSEA-1)-positive cells (SSEA-1 is a specific marker for pluripotent stem cells and is also expressed on VSELs) and reported their differentiation into PGCs, SSCs and spermatogonial cells.

Similar to our findings in mouse testes, Kurkure et al57 and Virant-Klun group5859 reported the presence of VSELs in azoospermic human testicular biopsies of cancer survivors and other clinical conditions (Fig. 3D). A recent systematic review60 has compiled data published by several groups reporting beneficial effects of transplanting MSCs in chemoablated mouse testes. However, none of these studies acknowledge presence of VSELs or throw any light on how transplanting MSCs could restore testicular function.

This understanding of testicular stem cells biology has significant implications in the field of oncofertility. Since VSELs survive oncotherapy in human testes, there may be no need to cryopreserve/bank testicular germ cells/biopsies. Azoospermic testes of cancer survivors are expected to harbour VSELs and a simple transplantation of niche cells - mesenchymal cells through intertubular route could enable restoration of spermatogenesis - thus ensuring biological parenthood.

VSELs in mammalian ovary

It is generally believed that mammalian ovary has fixed number of follicles which deplete with age and their sudden loss results in menopause. However, stem cells have been reported in the ovary surface epithelium (OSE) but are still debated61. There exist two distinct populations of stem cells in adult mammalian ovary including VSELs and OSCs similar to VSELs and SSCs in the testis62. Our group reported the presence of two populations of stem cells (Fig. 5) in rabbit, sheep, marmoset and human OSE cells63.

- Stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. (A) (i) Adult aged human ovary showing prominent ovary surface epithelial (OSE) cells with no follicles in the ovarian cortex, (ii) gentle scraping of ovary surface epithelial cells show the presence of spherical stem cells of two distinct sizes including very small embryonic-like stem cells (white arrow) and slightly bigger OSCs (black arrow) along with red blood cells, (iii) after H&E staining, very small embryonic-like stem cells (arrow) and OSCs (*) along with germ cell nest are clearly visualized. Source: Reproduced with permission from Refs 6364. (B) (i-iv) Confocal images of stem cells expressing OCT-4, (v-vi) OSCs in culture spontaneously differentiate into oocyte-like structures, polar body extrusion is also observed, (vii-viii) Parthenote embryo and hatching blastocyst in culture, (ix-x) embryonic stem-like colony, positive for alkaline phosphatise, (xi) embryoid body-like structure, (xii) neuronal-like structures, (xiii) at places, somatic fibroblasts surround an oocyte-like structure giving an impression of primordial follicle-like structure. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 63. (C) Sheep ovary surface epithelial cells smear shows the presence of VSELs (arrow) and OSCs (*) along with large number of epithelial cells, (ii) 15 h of follicle-stimulating hormone treatment resulted in extensive proliferation of stem cells and formation of germ cell nests whereas, (iii) untreated control did not show any change compared to initial culture. Source: Reproduced with permission from Ref. 65. (D) (i) Prominent single layer of ovary surface epithelial and stroma devoid of follicles in peri-menopausal ovarian tissue, (ii) loss of epithelial cells and disorganized stroma evident after three days in culture, (iii) follicle-stimulating hormone treatment results in proliferation and multi-layered appearance of ovary surface epithelial cells, (iv) chemoablated mouse ovary devoid of follicles, (v-vi) prominent ovary surface epithelial after follicle-stimulating hormone treatment to chemoablated mouse. Source: Reproduced with permission from Refs 6667.

We have published several observations on ovarian stem cells biology. Initially we observed a direct action of pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG) on adult mouse OSE. Treatment resulted in upregulation of pluripotent and meiotic markers along with increased numbers of primordial follicles below the OSE. It was concluded that PMSG activated the pluripotent VSELs and also appeared to augment neo-oogenesis and PF assembly in adult mouse ovaries68. OSE cells gently scraped from the ovaries of rabbit, sheep, marmoset and humans and enriched for the stem cells were found to have the ability to spontaneously differentiate into oocyte-like structures63. The epithelial cells attach to the bottom of the culture dish and provide feeder support whereas the stem cells spontaneously differentiate into oocyte-like structures, extrude polar bodies and parthenotes in vitro63. Further studies showed that events such as germ cell nest formation, Balbiani body and cytoplasmic streaming - which are characteristic of foetal ovaries are replicated while ovarian stem cells differentiate in vitro69 (Fig. 5A and B) and that this process is modulated by FSH66 (Fig. 5C). Contradictory results were published in a study70 which failed to detect any stem cell activity in adult ovary including formation of ‘germline cysts’ by lineage tracing approach and thus concluded that ovaries lacked stem cells. Our group suggested that absence of evidence was not necessarily evidence for absence for ovarian stem cells64.

In another experiment, sheep ovarian stem cells, enriched by gentle scraping of OSE were cultured in the presence of FSH resulted in activation of stem cells to undergo self-renewal and clonal expansion resulting in the formation of germ cell nests (Fig. 5C). Evidence was further generated that FSH action on ovarian stem cells (Fig. 5D, i-iii) was mediated through alternatively spliced FSHR3 isoform65.

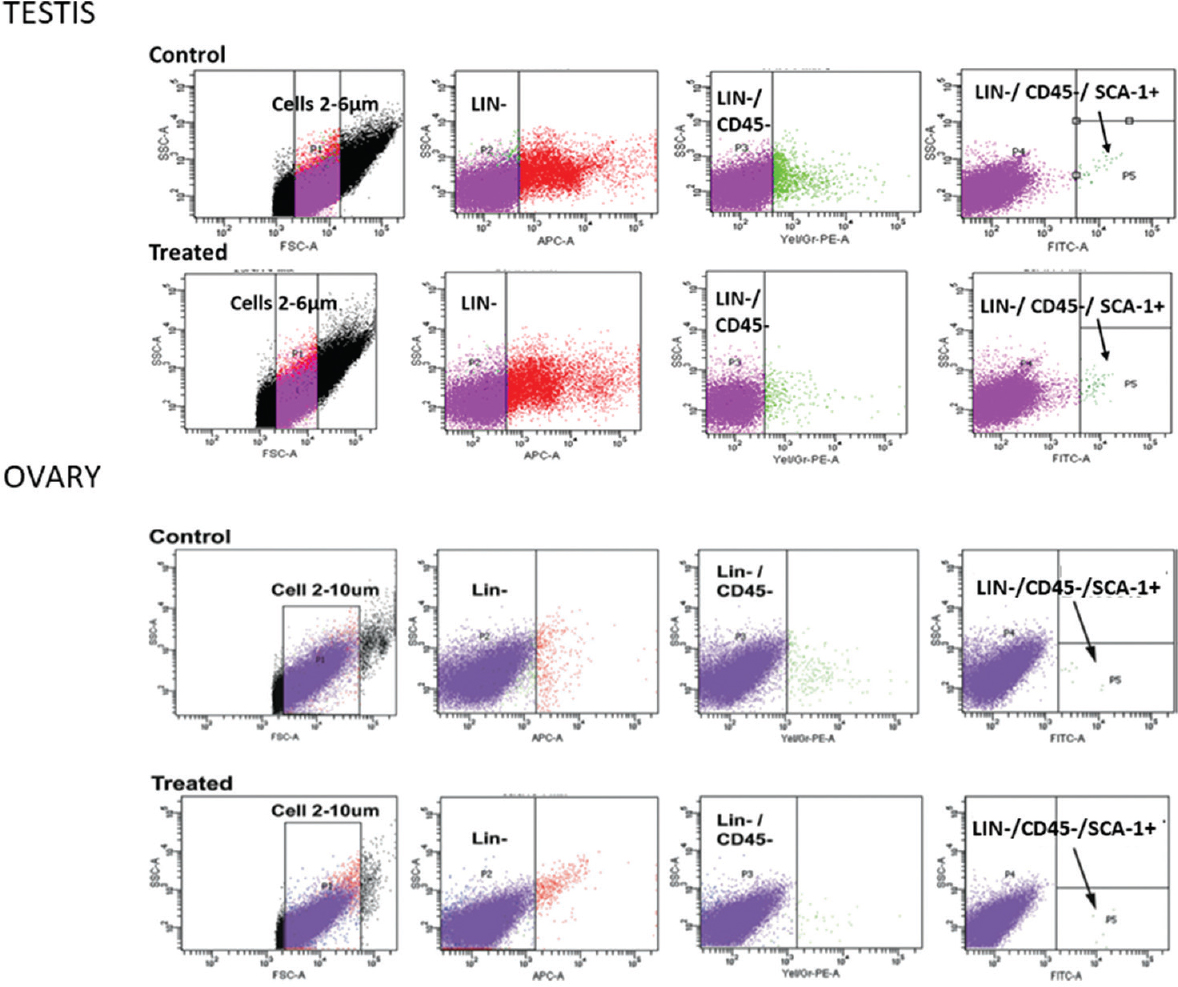

Chemoablation of mouse ovaries by treating with busulfan+cyclophosphamide resulted in complete depletion of follicles whereas the stem cells survived in the OSE67 (Fig. 5D, iv-vi). Treating chemoablated mice with PMSG (FSH analogue, 5 IU subcutaneously), after 48 h, resulted in increased numbers of VSELs with a cell surface phenotype of LIN-CD45-SCA-1+ (intact ovary have 0.02+0.01%; after chemoablation 0.03+0.017% and 0.08+0.03% after PMSG treatment to chemoablated mice) along with increased uptake of BrdU (Fig. 6). PMSG treatment during culture of chemoablated mouse ovaries resulted in stem cells’ proliferation and differentiation into pre-meiotic germ cell clusters (nests)67. These results provided evidence that VSELs survived chemotherapy in mice ovaries, were modulated by FSH, retained the ability to undergo oocyte-specific differentiation and could be the ideal endogenous stem cells to regenerate non-functional ovaries67. Initial evidence was provided to show primordial follicle assembly below the OSE71.

- Flow cytometry analysis of VSELs in adult intact and chemoablated mouse testis and ovary. VSELs are small in size (2-6 μm) and have a surface phenotype of LIN-CD45-SCA-1+. Their numbers are increased in the chemoablated gonads. VSELs were found to be 0.03 per cent in normal and 0.06 per cent in chemoablated testis and 0.02 per cent in normal and 0.03 per cent in chemoablated ovary of total events analyzed. Source: Reproduced with permission from Refs 5167.

Esmaeilian et al72 reported the presence of pluripotent stem cells in the mouse OSE with the ability to differentiate into the three germ layers and oocyte-like cells. Silvestris et al73 also confirmed the presence of two populations of stem cells in the human ovary and we discussed their findings74. VSELs and OSCs exist in ovary similar to VSELs and SSCs in the testis6274. Thus, it is evident that similar populations of pluripotent stem cells exist in ovary and testis which are developmentally equivalent to the PGCs, and being quiescent in nature, they survive oncotherapy. The stem cell-niche apparently gets compromised by oncotherapy and is unable to support stem cells’ differentiation into germ cells. This is true for both the testis and the ovaries. A simple replacement of the niche cells may allow surviving stem cells to regenerate non-functional ovaries.

Regenerating chemoablated testis and ovaries

It has been discussed that regenerating ovaries is a better approach rather than rejuvenating individual eggs by transplanting young mitochondria isolated from stem cells that exist in the ovarian cortex75. Also there is no need to transplant germ cells since stem cells survive in chemoablated testis. A simple transplantation of niche providing cells - Sertoli or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells through intertubular route could restore spermatogenesis in the chemoablated testes. A novel population of stem cells exists in the gonads and survives oncotherapy. This has been shown in both mouse testis and ovary by multiple techniques including flow cytometry (Fig. 6). A simple and direct transplantation of mesenchymal cells in the non-functional gonads may suffice to regenerate them.

Oktay et al76 reported four spontaneous pregnancies and three live births following subcutaneous transplantation of frozen-banked ovarian tissue at heterotopic site in a female survivor of Hodgkin lymphoma. The woman was earlier rendered menopausal due to preconditioning chemotherapy before bone marrow transplantation. They discussed that possibly the microenvironment of the non-functional ovary was destroyed by chemotherapy and paracrine/endocrine signals provided by the transplanted cortical tissue (at a heterotypic site) resulted in regeneration of the intact, non-functional ovary possibly by the stem cells from the bone marrow or resident stem cells. It has been suggested that ovarian stem-cell niche gets disrupted by chemotherapy and also with age777879. Aged, nonfunctional mouse ovaries were made functional on transplanting in a young host77 stressing on the fact that the stem cells niche gets compromised with age and that a healthy, young niche is crucial for stem cells function and oocyte development80. Birth of a child has been reported to a woman with premature ovarian failure on transplanting autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in the ovary81. This concept was discussed as a possible ray of hope for women with premature ovarian failure (POF)82.

To conclude, pilot clinical studies need to be undertaken to regenerate non-functional gonads of cancer survivors. In future, it would be possible to restore fertility in cancer survivors obviating the need to cryopreserve gonadal tissues before oncotherapy.

Financial support & sponsorship:

Financial support provided by the Department of Biotechnology, Department of Science and Technology and Indian Council of Medical Research, Government of India, New Delhi to various studies is acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest:

None.

Acknowledgment

Author acknowledges the contributions of Drs Seema Parte, Sreepoorna Unni, Sandhya Anand, Hiren Patel, Ambreen Shaikh and DST Woman Scientist Dr Kalpana Sriraman towards this review, and thanks to clinical collaborators including Drs Indira Hinduja and Purna Kurkure. Author also thanks Shri Vaibhav Shinde for help with the art work.

References

- International Society for Fertility Preservation–ESHRE–ASRM Expert Working Group. Update on fertility preservation from the Barcelona International Society for Fertility Preservation-ESHRE-ASRM 2015 expert meeting: Indications, results and future perspectives. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:407-15. e11

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of Indian gynecologists in oncofertility care and counselling. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2016;9:179-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oncologists’ role in patient fertility care: A call to action. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:171-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Legal battles over embryos after in vitro fertilization: Is there a way to avoid them? JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:182-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of very small embryonic-like stem cells to avoid legal, ethical, and safety issues associated with oncofertility. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:689.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of very small embryonic-like stem cells to avoid legal, ethical, and safety issues associated with oncofertility-reply. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:689-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility preservation in male patients with cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;55:59-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- A bioprosthetic ovary created using 3D printed microporous scaffolds restores ovarian function in sterilized mice. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15261.

- [Google Scholar]

- 86 successful births and 9 ongoing pregnancies worldwide in women transplanted with frozen-thawed ovarian tissue: Focus on birth and perinatal outcome in 40 of these children. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:325-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transplantation of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue: an update on worldwide activity published in peer-reviewed papers and on the Danish cohort. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:561-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation: What advances are necessary for this fertility preservation modality to no longer be considered experimental? Fertil Steril. 2019;111:473-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Live birth after orthotopic transplantation of cryopreserved ovarian tissue. Lancet. 2004;364:1405-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fertility preservation and refreezing of transplanted ovarian tissue-a potential new way of managing patients with low risk of malignant cell recurrence. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1206-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete in vitro oogenesis: Retrospects and prospects. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:1845-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cells, in vitro gametogenesis and male fertility. Reproduction. 2017;154:F79-F91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reconstitution of mouse oogenesis in a dish from pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:1733-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioengineering strategies to treat female infertility. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2017;23:294-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new strategy and system for the ex vivo ovary perfusion and cryopreservation: An innovation. Int J Reprod Biomed (Yazd). 2017;15:323-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microfluidic encapsulation of ovarian follicles for 3D culture. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:1676-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete meiosis from embryonic stem cell-derived germ cells in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:330-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Making gametes from pluripotent stem cells: embryonic stem cells or very small embryonic-like stem cells? Stem Cell Investig. 2016;3:57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cells in reproductive medicine: Ready for the patient? Hum Reprod. 2015;30:2014-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insights into in vitro spermatogenesis in mammals: Past, present, future. Mol Reprod Dev. 2017;84:560-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro differentiation of primordial germ cells and oocyte-like cells from stem cells. Histol Histopathol. 2017;10:11917.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complete in vitro generation of fertile oocytes from mouse primordial germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:9021-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiation of mouse primordial germ cells into functional oocytes in vitro . Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:1608-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Making gametes from alternate sources of stem cells: Past, present and future. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15:89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Derivation of pluripotent stem cells from cultured human primordial germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13726-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Derivation of human embryonic germ cells: An alternative source of pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21:598-609.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why are hematopoietic stem cells so 'sexy’. On a search for developmental explanation? Leukemia. 2017;31:1671-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel view of the adult stem cell compartment from the perspective of a quiescent population of very small embryonic-like stem cells. Circ Res. 2017;120:166-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endogenous, very small embryonic-like stem cells: Critical review, therapeutic potential and a look ahead. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;23:41-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shifting gears from embryonic to very small embryonic-like stem cells for regenerative medicine. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:15-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues: Struggling to be acknowledged over two decades. Stem Cell Rev. 2017;13:713-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel insights into adult and cancer stem cell biology. Stem Cells Dev. 2018;27:1527-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hematopoietic activity in putative mouse primordial germ cell populations. Mech Dev. 2015;136:53-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Very small embryonic-like stem cells: A potential developmental link between germinal lineage and hematopoiesis in humans. Stem Cells Dev. 2016;25:101-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel epigenetic mechanisms that control pluripotency and quiescence of adult bone marrow-derived Oct4(+) very small embryonic-like stem cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:2042-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Igf2-H19, an imprinted tandem Yin-Yang gene and its emerging role in development, proliferation of pluripotent stem cells, senescence and cancerogenesis. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2012;2:108.

- [Google Scholar]

- VSELs maintain their pluripotency and competence to differentiate after enhanced ex vivo expansion. Stem Cell Rev. 2018;14:510-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cells and progenitors in human peripheral blood get activated by extremely active resveratrol (XAR™) Stem Cell Rev. 2018;14:213-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4(+) SSEA-1(+) Oct-4+ stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20:857-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human and murine very small embryonic-like cells represent multipotent tissue progenitors, in vitro and in vivo . Stem Cells Dev. 2014;23:689-701.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mouse bone marrow VSELs exhibit differentiation into three embryonic germ lineages and germ & hematopoietic cells in culture. Stem Cell Rev. 2017;13:202-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel method for isolation of pluripotent stem cells from human umbilical cord blood. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26:1258-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Newer insights into premeiotic development of germ cells in adult human testis using Oct-4 as a stem cell marker. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:1093-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Very small embryonic-like stem cells survive and restore spermatogenesis after busulphan treatment in mouse testis. J Stem Cell Res Ther. 2014;4:216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Underlying mechanisms that restore spermatogenesis on transplanting healthy niche cells in busulphan treated mouse testis. Stem Cell Rev. 2016;12:682-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemoablated mouse seminiferous tubular cells enriched for very small embryonic-like stem cells undergo spontaneous spermatogenesis in vitro . Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) detected in azoospermic testicular biopsies of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testicular stem cells express follicle-stimulating hormone receptors and are directly modulated by FSH. Reprod Sci. 2016;23:1493-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- The quest for male germline stem cell markers: PAX7 gets ID’d. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4219-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of oncotherapy on testicular stem cells and niche. Mol Hum Reprod. 2017;23:654-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiation of bone marrow-derived stage-specific embryonic antigen 1 positive pluripotent stem cells into male germ cells. Microsc Res Tech. 2017;80:430-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential stemness of frozen-thawed testicular biopsies without sperm in infertile men included into the in vitro fertilization programme. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:291038.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small SSEA-4-positive cells from human ovarian cell cultures: Related to embryonic stem cells and germinal lineage? J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) therapy for recovery of fertility: A systematic review. Stem Cell Rev. 2018;14:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection, characterization, and spontaneous differentiation in vitro of very small embryonic-like putative stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1451-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian stem cells: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Follicle stimulating hormone modulates ovarian stem cells through alternately spliced receptor variant FSH-R3. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stimulation of ovarian stem cells by follicle stimulating hormone and basic fibroblast growth factor during cortical tissue culture. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mouse ovarian very small embryonic-like stem cells resist chemotherapy and retain ability to initiate oocyte-specific differentiation. Reprod Sci. 2015;22:884-903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gonadotropin treatment augments postnatal oogenesis and primordial follicle assembly in adult mouse ovaries? J Ovarian Res. 2012;5:32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamics associated with spontaneous differentiation of ovarian stem cells in vitro . J Ovarian Res. 2014;7:25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female mice lack adult germ-line stem cells but sustain oogenesis using stable primordial follicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:8585-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Further characterization of adult sheep ovarian stem cells and their involvement in neo-oogenesis and follicle assembly. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Putative germline and pluripotent stem cells in adult mouse ovary and their in vitro differentiation potential into oocyte-like and somatic cells. Zygote. 2017;25:358-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro differentiation of human oocyte-like cells from oogonial stem cells: Single-cell isolation and molecular characterization. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:464-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved understanding of very small embryonic-like stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. Hum Reprod. 2018;33:978-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Letter to the editor: Rejuvenate eggs or regenerate ovary? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;446:111-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Four spontaneous pregnancies and three live births following subcutaneous transplantation of frozen banked ovarian tissue: What is the explanation? Fertil Steril. 2011;95:804.e7-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aged mouse ovaries possess rare premeiotic germ cells that can generate oocytes following transplantation into a young host environment. Aging (Albany NY). 2009;1:971-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Failure of the stem cell niche rather than loss of oocyte stem cells in the aging ovary. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Manipulating ovarian aging: A new frontier in fertility preservation. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3:19-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stem cell interaction with somatic niche may hold the key to fertility restoration in cancer patients. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012:921082.

- [Google Scholar]

- Autologous stem cells therapy, the first baby of idiopathic premature ovarian failure. Acta Med Int. 2016;3:19-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is hope on the horizon for premature ovarian insufficiency? Fertil Steril. 2018;109:800-1.

- [Google Scholar]