Translate this page into:

Sex worker-led structural interventions in India: a case study on addressing violence in HIV prevention through the Ashodaya Samithi collective in Mysore

Reprint requests: Dr Sushena Reza-Paul, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada e-mail: rezapaul@cc.umanitoba.ca

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Structural interventions have the capacity to improve the outcomes of HIV/AIDS interventions by changing the social, economic, political or environmental factors that determine risk and vulnerability. Marginalized groups face disproportionate barriers to health, and sex workers are among those at highest risk of HIV in India. Evidence in India and globally has shown that sex workers face violence in many forms ranging from verbal, psychological and emotional abuse to economic extortion, physical and sexual violence and this is directly linked to lower levels of condom use and higher levels of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), the most critical determinants of HIV risk. We present here a case study of an intervention that mobilized sex workers to lead an HIV prevention response that addresses violence in their daily lives.

Methods:

This study draws on ethnographic research and project monitoring data from a community-led structural intervention in Mysore, India, implemented by Ashodaya Samithi. Qualitative and quantitative data were used to characterize baseline conditions, community responses and subsequent outcomes related to violence.

Results:

In 2004, the incidence of reported violence by sex workers was extremely high (> 8 incidents per sex worker, per year) but decreased by 84 per cent over 5 years. Violence by police and anti-social elements, initially most common, decreased substantially after a safe space was established for sex workers to meet and crisis management and advocacy were initiated with different stakeholders. Violence by clients, decreased after working with lodge owners to improve safety. However, initial increases in intimate partner violence were reported, and may be explained by two factors: (i) increased willingness to report such incidents; and (ii) increased violence as a reaction to sex workers’ growing empowerment. Trafficking was addressed through the establishment of a self-regulatory board (SRB). The community's progressive response to violence was enabled by advancing community mobilization, ensuring community ownership of the intervention, and shifting structural vulnerabilities, whereby sex workers increasingly engaged key actors in support of a more enabling environment.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Ashodaya's community-led response to violence at multiple levels proved highly synergistic and effective in reducing structural violence.

Keywords

Community-led

empowerment

HIV/AIDS

India

sex work

structural violence

The context of violence against sex workers

Global policy-makers recognize that effective HIV prevention requires locally contextualised approaches that address both individuals and social norms and structures, and are grounded in human rights12. The National AIDS Control Program began in 1992, with a priority to saturate prevention coverage of highly vulnerable groups like female sex workers (FSW), men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender individuals (TG) and injecting drug users (IDU) and, enhancing access and uptake of care, treatment and support3. The NACP III, sought to achieve 80 percent coverage of these groups, covering 2.34 million individuals, a 3-fold increase4.

The structural determinants considered to contribute to vulnerability among these groups56 are in many ways products of their marginalization7. Efforts to address the underlying factors (stigma and discrimination, collective agency8, alcohol abuse9 and violence10) are commonly referred to as structural approaches and seek to change the root causes or structures that affect individual risk and vulnerability to HIV11.

The Avahan India AIDS Initiative of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation supports structural interventions as part of the prevention response for 320,000 FSW, MSM and IDU in 6 states of India. These multi-level structural interventions were influenced by evidence showing an association between structural interventions and improved health outcomes1112.

The intersection between HIV prevention and violence has been the focus for some of the best-documented structural interventions in public health1213. Violence faced by sex workers has been identified as a major contributor to HIV vulnerability1415. Sex workers face violence in many forms- from social stigma, discrimination, intimidation, coercion and harassment to blatant physical and sexual violence. Experiences of violence affect communities from various geographical, cultural and economic settings1617. The perpetrators of violence are also diverse. Violence by police is among the most commonly reported types of violence1819. Sex workers face violence from anti-social elements (gangs or thugs), brokers or other ‘managers’2021, and intimate partner violence is also frequently reported19–22. Risk of client-initiated violence varies greatly by setting and may depend to a great extent on conditions where sex work takes place23. Finally, coercion, force and violence may be closely related to human trafficking1724. In response to these reports, various interventions have been devised. These have included community mapping, peer-based outreach, community organizing, advocacy, building allies, networking for creating an enabling environment and related environmental/structural interventions192526.

This case study describes how Ashodaya Samithi in Mysore, funded by Avahan, approached community-led structural interventions by allowing communities to lead the efforts. In 2004, sex workers in Mysore began organizing themselves to address HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They adopted structural interventions to address other occupational hazards, including violence. Within two years of initiation of the HIV intervention, sex workers organized themselves to form their own organization, called Ashodaya Samithi, in December 2005. The intervention integrated approaches proven effective in Sonagachi and other contexts where a health and human rights approach was undertaken27. It also incorporated community development and empowerment approaches proven to improve outcomes for marginalized groups in other settings2829. Although the sex worker-led response to violence is the focus of this paper, it rests on the premise that collectivization processes and transformations in sex workers’ relationships with local health services are a critical prerequisite of effective HIV prevention, as discussed elsewhere in the literature30–32. This case study highlights the positive outcomes of anti-violence work resulting from the community-led intervention using ethnographic field work, qualitative findings and programme monitoring data.

Material & Methods

In order to elucidate the temporal relationship between Ashodaya's mobilization process and the impact on violence experienced by sex workers in Mysore, we triangulated data from ethnographic field notes, qualitative interviews and routine programme monitoring data.

Ethnographic field notes: A rapid situation assessment was undertaken from November to December 2003 to characterize the landscape of sex work in Mysore before developing the intervention. Field notes from the lead author (SRP), one of 4 members of the project's implementation team, were used to define and describe the environment of sex work previous to the intervention as well as in the initial 12 weeks of the intervention. Field notes - from qualitative studies conducted in 2006 with male sex workers and in 2008 with community members and key external actors - documented sex work trajectories, the process and impact of sex worker mobilization, health seeking behaviours, project monitoring and experiences of violence.

Qualitative interviews: In addition to ethnographic field notes, research conducted in 2006 included 70 sexual life histories, where a team of 12 community researchers interviewed 5-6 male sex workers each. In 2008, 46 in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted by 4 masters-level students and included 34 interviews with sex workers (20 female, 14 male); 12 key informant interviews with community leaders, police officers, brokers, boyfriends and lodge owners; and 2 focus group discussions with female and male sex workers. The team also interviewed several members of the technical staff. Purposive sampling techniques were used to select interviewees.

Programme data/community-based monitoring system: Data used to assess baseline reports of violence and measure subsequent outcomes were obtained from a community-based monitoring system developed by the community in 2004 and enhanced over time with feedback from the field. In keeping with the vision and mandate of a community-led intervention, sex workers developed indicators that they deemed relevant to addressing HIV within their community. In addition to indicators related to STIs and HIV, community members developed specific indicators to measure different forms of violence. Incidents of violence were recorded by peer educators (guides) on their daily monitoring forms. The enabling environment team followed up on all reported incidents of violence in daily debriefing meetings. A structured form was designed to capture the details of each incident including measures taken to address it.

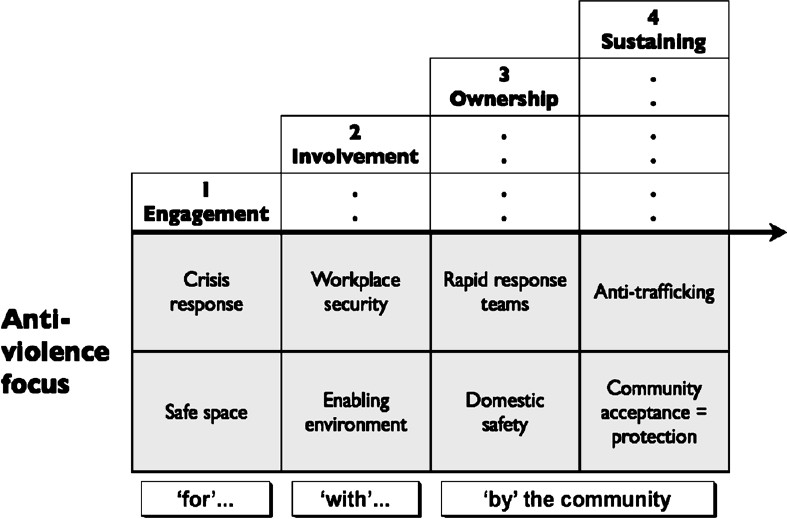

Data analysis: Reports of violence from the community-based monitoring system were interpreted through the ethnographic and qualitative data and further contextualized through consultations with sex workers, leaders and programme staff. Additional input was obtained from key informants including political leaders, police, lawyers, and social workers who have experience in areas of violence prevention and trafficking. From the analysis, a four-stage framework of community empowerment was devised: (i) Engagement; (ii) Involvement; (iii) Ownership; and (iv) Sustainability. Using this four-stage framework, temporal associations were explored between changes in monitored violence-related outcomes, specific community actions, and stages of community development.

Results

It was found that Ashodaya's community-led response to violence followed a progression whereby action taken at multiple levels proved highly synergistic and effective in confronting structural violence and addressing its root causes. The community's progressive response to violence was made possible by three changing factors in the context of the intervention: sex workers’ mobilization strengthened their collective agency; the intervention integrated mechanisms to build ownership of the intervention among sex workers, resulting in stronger self-efficacy for services including crisis response; and sex workers’ engagement with key actors to build a more enabling environment reduced stigma, discrimination and violence.

Ethnographic background: context of sex work, violence and HIV risk in Mysore: In 2004, a team of four health professionals launched an HIV prevention intervention among sex workers following an exploratory field visit and a situation assessment in Mysore. The project was initiated by engaging the community in participatory mapping, site assessments and assessments of existing service delivery and access. The team encountered a vibrant and thriving street-based sex work economy. Female sex workers (FSW) were dispersed, without cohesion or a shared sense of identity. Condom availability was found to be minimal. Voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) centres saw roughly 50 new HIV-positive people each month, yet no mention was made of sex workers being among those who were testing positive for HIV. According to key informant interviews, sex workers in Mysore at the time were highly unlikely to access health services at hospitals for fear of discrimination.

Importantly, violence was also found to be a part of the daily lives of Mysore sex workers. Both male and female sex workers reported regular harassment from police, anti-social elements and boyfriends in the form of monetary extortion, physical beatings and rape. In 2004, the incidence of reported violence by sex workers was extremely high, with more than 8 incidents per sex worker per year. The team concluded early on that any progress on health, and specifically HIV prevention, would depend on reducing the high levels of violence and intimidation faced by sex workers.

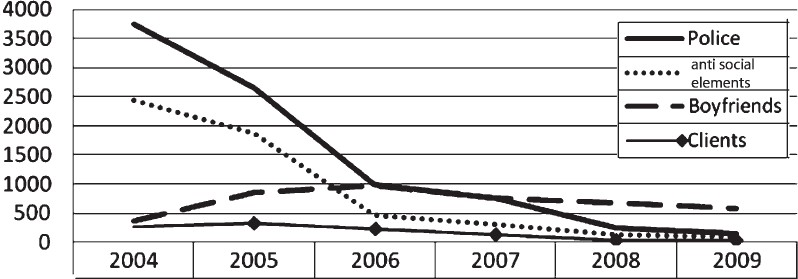

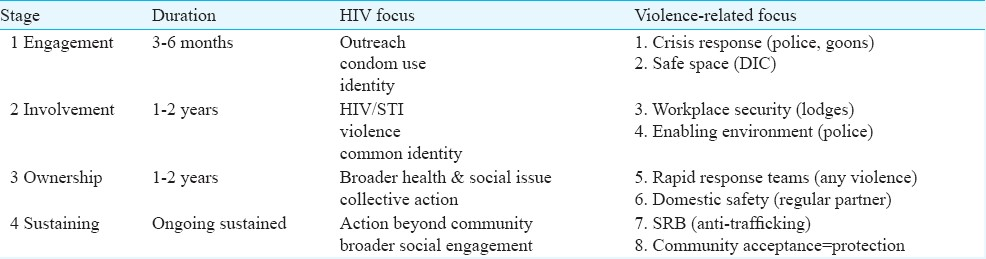

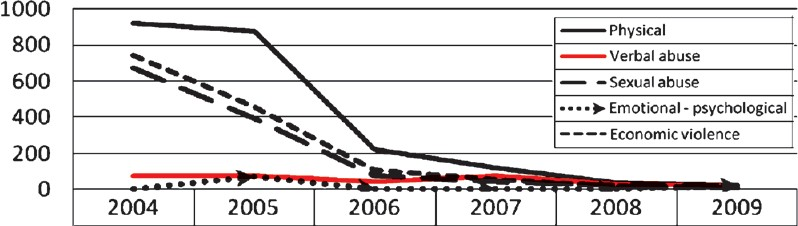

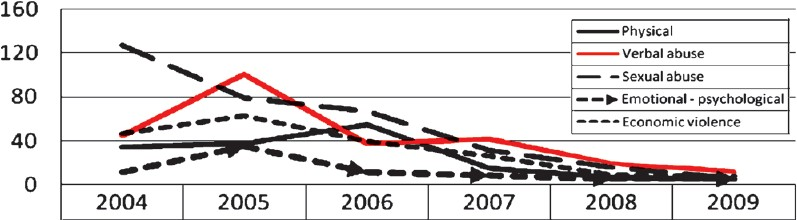

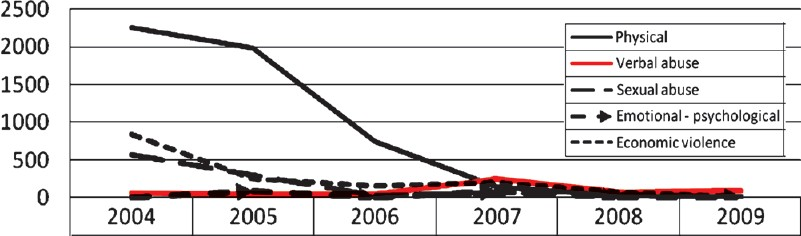

Fig. 1 shows the baseline levels of reported violence by perpetrator. Also depicted are the trends of violent incidents over the subsequent five years. Fig. 2 shows the trends of reported incidents of each type, with physical violence as the most commonly reported type of violence experienced.

- Violent incidents reported by sex workers, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2008.

- Type of violence reported by sex workers, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2009.

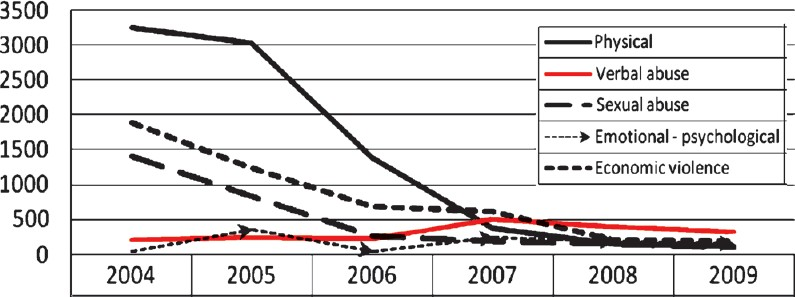

Initial synergistic response to violence: The team involved the community to conduct a rapid needs assessment and mapping followed by implementing the intervention. Violence reduction activities were integral to the plan. The framework relates specific actions to reduce violence, identify stages of community organization/empowerment, and HIV/health-related activities undertaken by the community (Table).

Stage 1: Engagement

Initial crisis response: During field visits, the team learned about and began to address the most immediate needs of sex workers, which included reducing police harassment, providing a safe space and having dedicated sexual health services. From the beginning, the team responded to various crisis situations. For example, they negotiated the release of FSW following police arrests, accompanied them to health facilities during emergencies, and responded immediately to partner and anti-social elements violence.

Anti-social elements violence: In 2004, many sex workers were controlled by anti-social elements, pimps and “agents” who lived off FSWs’ earnings. Overt violence was common. As sex workers began to take control of their lives and come together as a community, reports of anti-social elements violence fell rapidly (Fig. 3).

- Violent incidents by anti-social elements, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2009.

Safe space: exchanging protective strategies at the drop-in centre (DIC): As the FSW demanded a safe space, the team consulted with the community and jointly located a site for a drop-in centre (DIC). The FSW asked for a clinic in the DIC, and thus health service delivery was initiated. By the end of the first year, almost 75 per cent of the estimated sex worker population had begun to access services at the clinic.

Initially, the DIC operated as an unregulated space with no conditions of use attached to it. The goal was to create a space for FSW where external rules did not govern their freedom and they could use the space and the opportunity of interacting in it to usher in a significant phase of collectivization. At the DIC, sex workers began to interact with each other and soon recognized that they shared common problems and experiences.

Stage 2: Involvement

Workplace security: reinforcing protection in the lodges: The safe space afforded by the DIC quickly moved from a “problem-sharing” to a “problem-solving” space. Although the programme team initially engaged in crisis management, their role as the primary problem-solvers gradually retreated as sex workers began to hold more formalized meetings to strategize solutions to their problems. During the earliest phase of the project, sex workers began to realize that the social networks forming through the DIC afforded them protection by reducing isolation.

Beginning in early 2005, the intervention began creating safe spaces beyond the DIC by building rapport with lodge owners who provided rooms for sex work. Negotiations with lodge owners ensured that sex workers were able to maintain control during their transactions with clients.

Client violence: Client-initiated violence has always been less common than other types. Sex workers always negotiated relatively safe settings for sex. In addition to this, the community was able to distinguish between clients and anti-social elements who disguised as clients. As the project and community became more involved in actions to prevent violence, lodge owners, brokers and others who were part of the sex work industry were targeted as key stakeholders, and reports of all types of client violence declined further (Fig. 4).

- Violent incidents by clients, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2009.

This ongoing relationship is sustained through the mutual benefits enjoyed by lodge owners and sex workers. Lodge owners accessed free health services from Ashodaya, and they in turn provided protection for sex workers if clients became abusive.

Enabling environment: working work with police: Prior to Ashodaya's formation, sex workers endured extreme forms of discrimination and harassment from the police in the form of beatings, arrests, raids and coerced sex, often without condoms. Sex workers aimed to minimize these experiences of violence by attempting to keep their identities hidden. Since the formation of Ashodaya, relationships between sex workers and the police have improved radically. In 2005, a meeting was conducted by the District Collector, Corporation Commissioner and Police Commissioner along with representatives of lodge owners. The Police Commissioner agreed to allow condoms to be stored at the lodges where sex work takes place, without running the risk of police raids and arrests. Sex workers have also become aware of the laws pertaining to sex work and are able to dialogue with the police. Violent incidents involving the police declined rapidly during the first 2 years as a result of the crisis management response and advocacy work undertaken by Ashodaya (Fig. 5).

- Violent incidents by police, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2009.

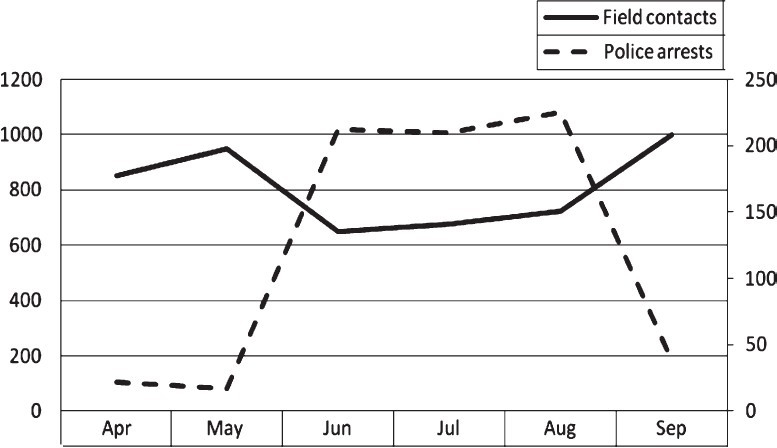

It is important to note the effect that police violence can have on service utilization. During a period in 2006 when there was a sharp increase in police arrests, Ashodaya documented an almost 40 per cent drop in outreach contact (Fig. 6).

- Police arrests and Ashodaya field contacts, 2006.

Stage 3: Ownership

Rapid response teams: Community-led protection extended from the DIC into the field as sex workers began developing and implementing their own strategies to avoid dangerous situations with various stakeholders, such as discussing how to negotiate safe locations with clients and informing peers when going to an uncommon place with clients. The sex workers obtained legal literacy, negotiation skills and on-the-job training on how to handle crises. The rapid response team, which initially comprised of seven sex workers and two non-community staff, now consisted of all sex workers. Almost all sex workers carried cell phones, so the rapid response effort operated through a cell phone network. The cell phone numbers of the rapid response team were given to all sex workers to call. The staffing of the team was changed every month so that individuals were not overburdened. Currently Ashodaya's strategy has moved beyond responding to crises towards planning activities to prevent crises by developing safety mechanisms, including having community guides patrol locations in Mysore where sex work is most concentrated.

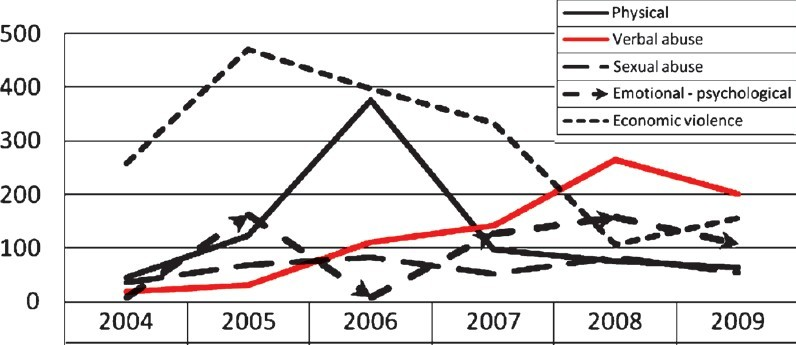

Domestic safety: challenging power dynamics with regular partners: There appears to be a complex relationship between empowerment among FSW and reports of domestic violence from regular partners. In the early phase of the project, reports of police violence decreased but reports of domestic violence committed by regular partners increased (Fig. 7). This suggests that domestic violence may function as a proxy indicator for empowerment, albeit a counterintuitive one. In the context of increased empowerment, it remains unclear whether sex workers are actually facing more violence from their regular partners, or if they are simply more able to recognize violence and feel more empowered to report these experiences. The early rise in reported incidents may also have resulted from the reaction of regular partners to the assertiveness of women identifying with Ashodaya's political ideals. This demonstrates that empowerment may not proceed along a linear path to “progress”; new tensions and disruptions arise as interpersonal relations are transformed around the intervention.

- Violent incidents by boyfriends, Ashodaya Samithi, 2004-2009.

Stage 4: Sustaining

Self-regulatory boards: violence and anti-human trafficking: Violence is also intrinsically linked with human trafficking. Traffickers commonly use coercion, force and overt physical and sexual violence to control their victims. Violence against sex workers, including unwarranted arrests and forced confinement, has also been reported following “raid and rescue” operations by police and others. Following early attempts to assist minor girls or women in sex work against their will, Ashodaya looked closely at self-regulatory boards (SRB), such as those implemented by Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC) in West Bengal, and in 2009 decided to replicate this approach33. Community members made up the majority of the board, with non-community members representing important civil and professional sectors including education, health, legal, social welfare, and the police. Ashodaya peer guides make daily contact in the field, and when a newcomer arrives, the peer guide will identify her and a counselling session is arranged. If she is a minor or has been introduced into sex work by coercion, she is given the options of being reintegrated with her family or staying at a hostel to undergo other vocational training. In the case of family reintegration, Ashodaya representatives will take her home and obtain a written undertaking from her family that she will not be sent back into sex work. Routine follow up of such cases is done. Since 2004, the majority of women were willing adults (96.3%) and only a small percentage (3.4%) was of minor girls.

Becoming a community-led intervention: community acceptance = protection: With the establishment of Ashodaya, sex workers began to recognize that community health protection needed to go beyond a narrow definition of “hot spots” that only recognizes the places where sex workers meet or have sex with clients. For effective HIV prevention, their efforts also needed to confront the various structures that reproduced and maintained their marginality.

Discussion

Violence may be among the best-documented structural factors directly linked to HIV risk in India and globally3435. Interventions that seek to change structural factors have been a component of health interventions for some decades, although the complexity of measuring outcomes and attributing them directly to structural interventions has been problematic. This case study argues that a structural intervention must grow from a strong collectivization process and transformations in sex workers’ relationship with local partners in responding to rapidly changing contexts and addressing multiple risk factors simultaneously.

Letting the community define and follow its own agenda rather than steering it towards goals that may have been predetermined by the intervention is crucial, but is a well-documented challenge3637. Mobilization of sex workers is a critical element of community-led structural interventions because the collective power gained through this process helps to alter the power dynamics between a marginalized group and the individuals and institutions with which that group interacts38. Ashodaya experienced some non-linear effects of structural interventions whereby violence was seen to increase, police behaviour went from supportive to punitive, and supportive political leaders were replaced and new relationships had to be formed. At such points Ashodaya had to change course in its policy-level structural approaches to take advantage of different opportunities to overcome obstacles. Finally, when the relationship between structural interventions and outcomes has been measured it can be a challenge to find exactly the right indicators and produce data with adequate power to show direct causality3940.

Ashodaya's approach to community mobilization both reflected and informed Avahan's approach across the six States where it worked. The community's participation in addressing violence grew out of its prior involvement in delivering the service package for HIV prevention, including peer-led outreach and membership of committees to oversee clinical services, commodity distribution, the running of the DIC, and advocacy. The experience and skills gained in these areas made it possible for community members to be effective when addressing issues that they themselves defined as priorities, such as violence and access to health care, education and government entitlements.

Avahan disseminates learning and propagates best practices from its interventions through semi-annual meetings with senior leadership from its lead partners, where innovations and programme refinements were presented and discussed. Community mobilization has been a vital focus in most of these meetings39. Innovative approaches from different partners such as Ashodaya's crisis response team, deeper understanding and approaches towards community and structural interventions were incorporated in Avahan's Common Minimum Program (CMP)41. This was initially created in 2004, and revised in 2006 and 2010. The CMP continued to incorporate new lessons and was one of the management tools used by Avahan as an attempt to provide an ongoing measurable, minimum package of prevention interventions which was delivered across the program, based on global and Avahan experiences.

Ashodaya's work in combating violence is typical of Avahan's interventions in being closely linked to broader community mobilization and empowerment work. In 2004, at the start of the initial intervention in Mysore, violence was extremely common. Police and anti-social elements violence were most commonly reported. At the time, sex workers acknowledged that acts of violence were probably underreported, particularly violent incidents involving regular partners. These trends changed markedly over the subsequent years. Fig. 8 illustrates the close alignment of anti-violence interventions with stages of developing community empowerment and ownership.

- Anti-violence focus by stages of community empowerment, Ashodaya Samithi.

During the first stage (engagement), activities are mostly carried out by project staff “for” the community. In the second stage (involvement), actions are carried out “with” the community as sex workers themselves began to take a more active role as implementers. Beginning with the formation of Ashodaya as a CBO, stages are characterized by actions carried out “by” the community. Activities during this third stage (ownership) address a broader range of health and social issues of importance to the community. This extends during the fourth stage (sustaining) to activities beyond the immediate benefit of the sex worker community, including public service and capacity-building with other communities.

Ashodaya's community-led response to violence followed a progression whereby action taken at multiple levels proved highly synergistic and effective in confronting structural violence. Despite drastic reductions in experiences of violence, concerns about safety persist as sex work changes and new forms of solicitation are used. Cell phones are increasingly employed to fix clients, and encounters take place in a wider range of locations. Concern about isolation and safety has led community members to come up with new approaches to negotiating venues and other details, and to finding innovative ways to communicate so that sex workers in need can call for help. Ashodaya's success in mobilizing a community of sex workers to address violence at multiple levels holds valuable lessons for other community-led interventions working to address HIV prevention.

In conclusion, the community-led approach was a prerequisite for the development of the structural intervention. Building capacity of the community was critical so that they could exert their positional power and have collective bargaining power. Such capacity-building should be integral to targeted interventions4 and therefore, should be adequately budgeted for. As policy makers globally and in India endeavour to make HIV prevention a viable prospect in a concentrated epidemic, this case study shows that it can only be successful if community-driven structural interventions are undertaken.

The authors acknowledge all the community members for sharing their life stories, helping us to understand the different dimensions of the problems that they encounter in their daily lives, and for their heroic endeavours in overcoming them. Authors thank all the team members of Ashodaya Samithi for assisting in the intervention. Special thanks to Dr S. Sundararaman and Dr S. Jana for mentoring Ashodaya. Support for this study was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through Avahan, the India AIDS Initiative.

References

- Coming to terms with complexity: a call to action for HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:845-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing out vulnerability, building in respect: violence, safety and sex work policy. Br J Sociol. 2007;58:1-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Containing HIV/AIDS in India: the unfinished agenda. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:508-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Organisation (NACO). Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. In: National AIDS Control Programme Phase III (2006-2011). New Delhi: NACO; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Informing interventions: the importance of contextual factors in the prediction of sexual risk behaviors among transgender women. AIDS Edu Prev. 2009;21:113-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transforming social structures and environments to help in HIV prevention. Health Aff (Millweed). 2009;28:1655.

- [Google Scholar]

- Power, community mobilization, and condom use practices among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 5):S109-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol use among female sex workers and male clients: an integrative review of global literature. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:188-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- An integrated structural intervention to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:755.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intimate partner violence, HIV status, and sexual risk reduction. AIDS Behav. 2002;6:107-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- History of sex trafficking, recent experiences of violence, and HIV vulnerability among female sex workers in coastal Andra Pradesh, India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;114:101-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Violence against female sex workers in Karnataka state, south India: impact on health, and reductions in violence following an intervention program. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:476.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- A profile of HIV risk factors in the context of sex work environments among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:172-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Violence, dignity and HIV vulnerability: street sex work in Serbia. Sociol Health Ill. 2009;31:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protecting the unprotected: mixed-method research on drug use, sex work and rights in Pakistan's fight against HIV/AIDS. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(Suppl 2):ii31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:140-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:911-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk and danger among women who prostitute in areas where farmworkers predominate. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:251-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sexual risk behaviors, alcohol abuse, and intimate partner violence among sex workers in Mongolia: implications for HIV prevention intervention development. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38:89-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intimate partner violence is as important as client violence in increasing street-based female sex workers’ vulnerability to HIV in India. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19:106-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sex trafficking, sexual risk, sexually transmitted infection and reproductive health among female sex workers in Thailand. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:334-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Searching for justice for body and self in a coercive environment: Sex work in Kerala, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2004;12:58-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009;339:b2939.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Sonagachi Project: a sustainable community intervention program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16:405-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- A framework linking community empowerment and health equity: it is a matter of CHOICE. J Health, Popul Nutr. 2003;21:168-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the social and cultural contexts of female sex workers in Karnataka, India: implications for prevention of HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S139-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Confronting structural violence in sex work: lessons from a community-led HIV prevention project in Mysore, India. AIDS Care. 2011;23:69-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Declines in risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infection prevalence following a community-led HIV preventive intervention among female sex workers in Mysore, India. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 5):S91-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- On Becoming a male sex worker in Mysore: sexual subjectivity, “empowerment”, and community-based HIV prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 2009;23:142-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Durbar's (DMSC) position on trafficking and the formation of Self Regulatory Board. Int Conf AIDS. 2004;15 abstract no. WePeD6547

- [Google Scholar]

- Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behavior among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20:2107-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against women study team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B, Kothari U, eds. Participation: the new tyranny?. London, New York: Zed Books; 2001.

- Hickey S, Mohan G, eds. Participation, from tyranny to transformation?: exploring new approaches to participation in development. London, New York: Zed Books; 2004.

- Structural interventions: Concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83:59-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Learning about scale, measurement and community mobilisation: Reflections on the implementation of the Avahan HIV/AIDS Initiative in India. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011 In press

- [Google Scholar]

- Navigating the swampy lowland: a framework for evaluating the effect of community mobilization in female sex workers in Avahan, the India AIDS Initiative. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011 In press

- [Google Scholar]

- Avahan India AIDS Initiative and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In: Avahan Common Minimum Program. New Delhi: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; 2010.

- [Google Scholar]