Translate this page into:

Role of inducers in detection of blaPDC-mediated oxyimino-cephalosporin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Reprint requests: Dr. Amitabha Bhattacharjee, Department of Microbiology, Assam University, Silchar 788 014, Assam, India e-mail: ab0404@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Pseudomonas aeruginosa possessing chromosomally inducible blaPDC along with other intrinsic mechanism causes infection with high mortality rate. It is difficult to detect inducible AmpC enzymes in this organism and is usually overlooked by routine testing that may lead to therapeutic failure. Therefore, three different inducers were evaluated in the present study to assess their ability of induction of blaPDC in P. aeruginosa.

Methods:

A total of 189 consecutive Pseudomonas isolates recovered from different clinical specimens (November 2011-April 2013) were selected for the study. Isolates were screened with cefoxitin for AmpC β-lactamases and confirmed by modified three-dimensional extract test (M3DET). Inductions were checked using three inducers, namely, clavulanic acid, cefoxitin and imipenem along with ceftazidime. Molecular screening of AmpC β-lactamase genes was performed by PCR assay. Antimicrobial susceptibility and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined, and repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR of all blaPDC harbouring isolates was performed.

Results:

Inducible phenotype was observed in 42 (24.3%) of 97 (56%) isolates confirmed by M3DET. Among these, 22 isolates harboured chromosomal blaPDC gene, and cocarriage of both chromosomal and plasmid-mediated blaAmpC genes was observed in seven isolates. Cefoxitin-ceftazidime-based test gave good sensitivity and specificity for detecting inducible AmpC enzymes. Isolates harbouring blaPDC showed high MIC against all tested cephalosporins and monobactam. DNA fingerprinting of these isolates showed 22 different clones of P. aeruginosa.

Interpretation & conclusions:

P. aeruginosa harbouring inducible (chromosomal) and plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase is a matter of concern as it may limit therapeutic option. Using cefoxitin-ceftazidime-based test is simple and may be used for detecting inducible AmpC β-lactamase amongst P. aeruginosa.

Keywords

AmpC β-lactamase

blaPDC

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common nosocomial pathogens that causes infection with high mortality rate1. Antipseudomonal chemotherapy for these organisms is of great concern since these organisms possess chromosomally inducible Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinases (PDC) with broad-spectrum activity along with other intrinsic mechanisms. Further, it may also possess other inducible plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases such as ACT-1, DHA-1, DHA-2, DHA-23 and CMY-13 that could limit therapeutic option234. Induction of AmpC β-lactamases takes place mainly in response to several β-lactam and non-β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin group of drugs (ampicillin and amoxicillin) and cephalosporins group of drugs (cefazolin, cephalothin and cefoxitin) which act as strong inducers and good substrates for AmpC β-lactamase. Carbapenem group of drug (imipenem) also acts as strong inducers but is much more stable for hydrolysis. Cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefuroxime, piperacillin and aztreonam are weak inducers and weak substrates but can be hydrolyzed if enough enzymes are synthesized56. Other non-β-lactam antibiotics such as clavulanic acid also act as an inducer7. Currently, there is no Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline for phenotypic screening or confirmatory test for inducible AmpC β-lactamase producing bacteria. Based on inducing capabilities of imipenem on AmpC β-lactamase, ceftazidime-imipenem antagonism test (CIAT) was developed which showed good efficiency in detecting inducible AmpC β-lactamase amongst Enterobacteriaceae familly8. Since P. aeruginosa involves various intrinsic resistance mechanisms other than harbouring β-lactamases; it is difficult to detect accurate inducible AmpC β-lactamase in this organism910. Therefore, three different inducers were evaluated in this study to assess their ability of induction of blaAmpC in P. aeruginosa.

Material & Methods

A total number of 189 consecutive, non-duplicates, Pseudomonas isolates were selected for this study. These isolates were collected from different clinical specimens (urine, pus, stool, ear swab, throat swab, oral swab, sputum, ascitic fluid, drain tip, blood, conjunctival scraping, urethral discharge and ear discharge) spanning a period of 18 months (November 2011-April 2013) from different Wards/OPD of Silchar Medical College and Hospital, Silchar, Assam, India. The isolates were identified by cultural characteristics, pigment production and 16S rDNA sequencing.

Screening of ampC β-lactamase by cefoxitin and modified three-dimensional extract test (M3DET)

Preliminary screening of AmpC β-lactamase was carried out on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) (HiMedia, Mumbai) plates containing single antibiotic disk, namely cefoxitin (30 μg) (HiMedia). Isolates with inhibition zones of <18 mm to cefoxitin were considered as screen positives isolates11. The suspected AmpC β-lactamase producers were further confirmed by M3DET12. Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Enterobacter cloacae P99 were used as a negative and positive control, respectively.

Detection of inducible ampC β-lactamase

Induction experiment was performed with slight modification of CIAT8. Imipenem (10 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg) and clavulanic acid (30 μg) (HiMedia) were used to check the potentiality to induced AmpC β-lactamase. The discs were placed 20 mm apart (centre-to-centre) from a ceftazidime disk (30 μg) on a MHA plate previously inoculated with a 0.5 McFarland bacterial suspension and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Antagonism, indicated by a visible reduction in the inhibition zone around the ceftazidime disk adjacent to the imipenem, clavulanic acid or cefoxitin disk, was regarded as positive for inducible AmpC β-lactamase production. Sensitivity and specificity of the tests were evaluated by statistical analysis.

Antimicrobial susceptibility and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs)

Antimicrobial susceptibility was determined by Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method13 on MHA plates. The following antibiotics were used: amikacin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), ciprofloxacin (30 μg), trimethoprim/sulphamethoxazole (1.25/23.75 μg), cefepime (30 μg), imipenem (10 μg), meropenem (10 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg) and aztreonam (30 μg) (HiMedia). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of various antibiotics were determined on MHA plates by agar dilution method according to CLSI guidelines14 using the following antibiotics: cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem and aztreonam (HiMedia).

Detection of bla PDC by PCR

For amplification and characterization of blaPDC genes, forward 5'-ATGCAGCCAACGACAAAGG-3' and reverse primers 5'-CGCCCTCGCGAGCGCGCTTC-3' were used2. PCR amplification was performed using 30 μl of total reaction volume. Reactions were run under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for two minutes, 32 cycles of 95°C for 20 sec, 58°C for 40 sec, 72°C for 1.2 min and final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR product was run on 1 per cent agarose gel and visualized in Gel Doc EZ imager (Bio-Rad, USA).

Multiplex PCR assay for detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase

Multiplex PCR was performed on all the AmpC β-lactamase positive isolates targeting all the AmpC β-lactamase gene families, namely, CIT, DHA, ACC, FOX and EBC15. PCR amplification was performed using 30 μl of total reaction volume. Reactions were run under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for two minutes, 34 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 51°C for one minute, 72°C for one minute and final extension at 72°C for seven minutes. The PCR product was run on 1 per cent agarose gel and visualized in Gel Doc EZ imager (Bio-Rad, USA).

DNA fingerprinting by repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP) PCR

Typing of all blaPDC producing isolates was done by REP- PCR as described previously16.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity and specificity of the phenotypic screening tests for the detection of AmpC β – lactamase was done when compared with three different inducers i.e., imipenem, cefoxitin and clavulanic acid. Statistical analysis was performed taking M3DET as gold standard.

Results

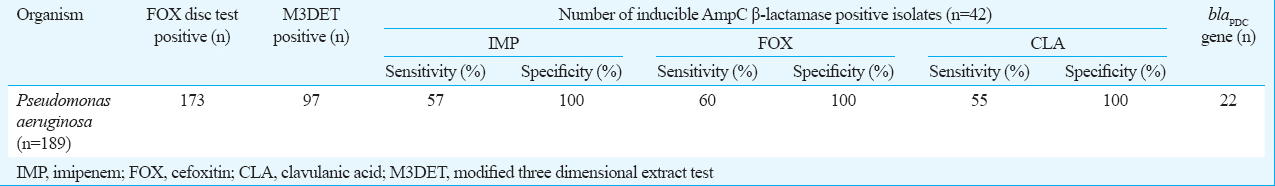

Of the 189 isolates, 173 (91.5%) were resistant to cefoxitin. On performing M3DET, 97 (56%) isolates were found to show AmpC β-lactamase activity. However, inducible AmpC β-lactamase was detected only in 42 (24.3%) isolates. A higher number of induction was observed against cefoxitin (n=31) followed by imipenem (n=25) and clavulanic acid (n=17) (Table I). In contrast, seven isolates showed induction against both imipenem and cefoxitin, one isolate for both imipenem and clavulanic acid, four isolates for both cefoxitin and clavulanic acid and seven isolates showed induction against all the three inducers.

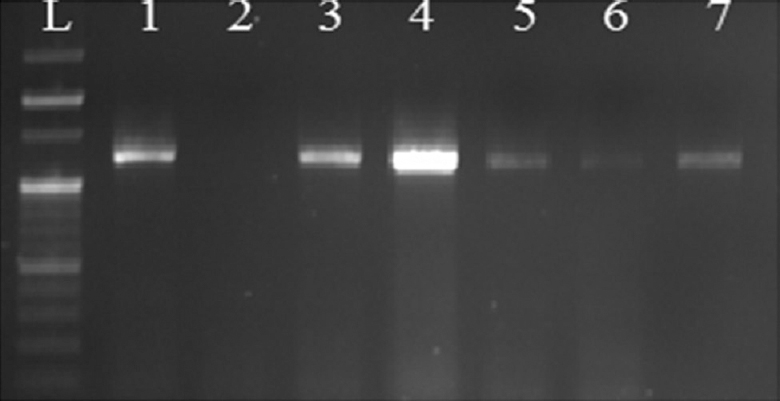

Genotypic detection of chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase showed that 22 isolates harboured blaPDC gene (1243bp) (Fig. 1). Of the 22 chromosomal harbouring β-lactamase isolates, 19 showed phenotypic inducibility. On performing multiplex PCR, plasmid-mediated blaAmpC genes were detected among 51 isolates and were found to be CIT, DHA and EBC family (20, CIT; 19, DHA and 12, EBC). However, only 14 plasmid-mediated blaAmpC genes were observed among phenotypically inducible AmpC β-lactamase-positive isolates. It was also observed that seven isolates were harbouring both chromosomal and plasmid-mediated blaAmpC genes.

- Gel image showing amplification of Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinases gene: Lane L, 100 bp DNA ladder; lanes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinases gene (1243 bp); lane 2, negative control.

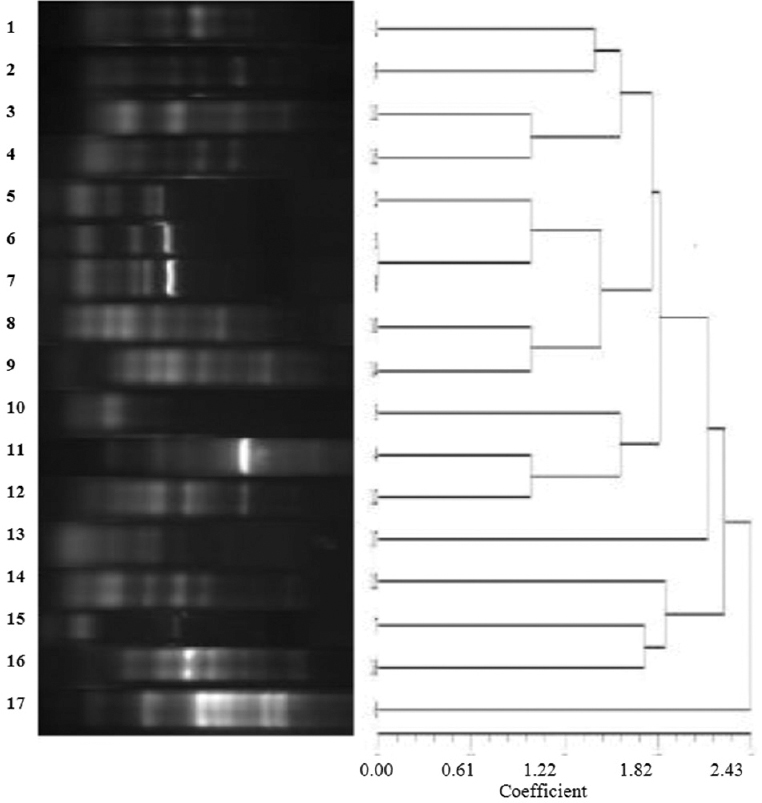

M3DET was used as gold standard for calculating sensitivity and specificity. For imipenem-ceftazidime-based test, sensitivity was found out to be 57 per cent, cefoxitin-ceftazidime based test 60 per cent and clavulanic acid-ceftazidime based test 55 per cent. All these tests showed 100 per cent specificity for detecting inducible AmpC β-lactamases (Table I). DNA fingerprinting of all the blaPDC harbouring isolates by repetitive PCRs showed 17 different clones of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2).

- Dendrogram to illustrate the clonal differences of blaPDC producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates.

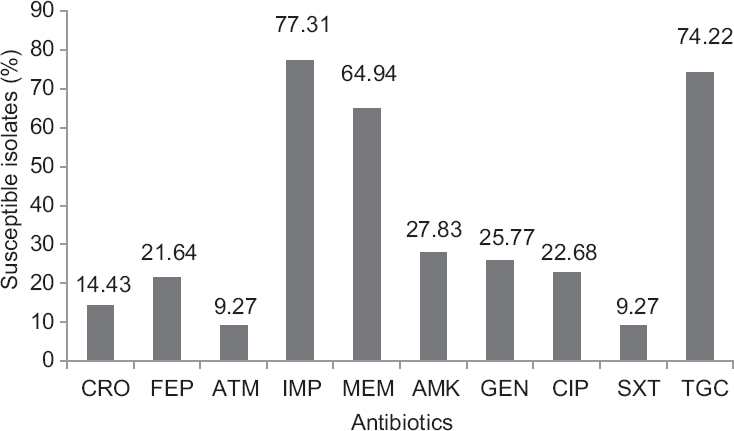

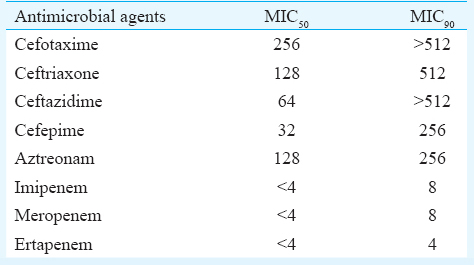

Susceptibility results showed that most of the blaPDC harbouring isolates were susceptible to carbapenem group of drugs. Other antibiotics such as ceftriaxone, cefepime, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and co-trimoxazole showed moderate to lower activity (Fig. 3). A high MIC was noticed against all tested cephalosporins and monobactam; however, MIC50 of isolates against carbapenems were at the susceptible range (Table II).

- Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of AmpC positive isolates against β-lactam and non-β-lactam antibiotics. CRO-ceftriaxone, FEP- cefepime, ATM-aztreonam, IMP-imipenem, MEM-meropenem, AMK-amikacin, GEN-gentamicin, CIP-ciprofloxacin, SXT-co-trimoxazole, TGC- tigecycline

Discussion

Organisms producing chromosomally inducible AmpC β-lactamase are usually overlooked by routine testing as these often do not show resistance to third-generation cephalosporins. Clinical use of cephalosporins against these isolates could segregate resistant mutants that would ultimately result in therapeutic failure. Therefore, current detection methods for screening of inducible AmpC β-lactamase producing organisms are technically demanding. There is also a paucity of data regarding inducible AmpC β-lactamases worldwide. It was observed that 24.3 per cent isolates in the present study harboured these enzymes which corroborated with earlier studies1718. Of the three inducers used in this study, cefoxitin showed higher ability to induce AmpC β-lactamase with sensitivity of 60 per cent followed by imipenem and clavulanic acid. This finding was supported by another study where cefoxitin was established to be a potent inducer of class C β-lactamase in P. aeruginosa19. Clavulanic acid showed moderate inducing capabilities as reported in earlier studies720.

Induction phenotype observed in P. aeruginosa could be due to PDC which has three AmpD homologues to regulate the expression of AmpC β-lactamase2122. In the present study blaPDC gene was screened in P. aeruginosa isolates that were phenotypically confirmed for AmpC β-lactamase activity and 23 per cent isolates showed blaPDC gene which was supported by earlier study23. It was observed that 19 isolates harbouring blaPDC showed inducible AmpC phenotype. These isolates showed resistant profile against third- andfourth-generation cephalosporins and monobactams but most of these showed susceptible profile against carbapenem antibiotics. Ten variants of blaPDC(PDC 1-10) gene have been reported worldwide which have reduced susceptibilityfor third- and fourth-generation cephalosporin and carbapenem2.

The discovery of inducible chromosome-mediated AmpC β-lactamase requires re-evaluation of the treatment option available for patients infected with pathogens expressing this resistance mechanism. Presence of additional plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase showing expanded spectrum cephalosporin-resistant phenotype would further complicate the antibiotic policy and therapeutic options in nosocomial infections caused by these isolates. Use of cefoxitin along with ceftazidime is a simple method and may be used for routine detection of chromosomally inducible AmpC β-lactamase amongst P. aeruginosa.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the help of Head, Department of Microbiology, Assam University, for providing infrastructure. Financial support provided by University Grants Commissions UGC-MRP and UGC-RGNF, Government of India and Department of Biotechnology (DBT-NER Twinning Scheme) is acknowledged. Authors thank the Assam University Biotech Hub for providing laboratory facility to complete this work.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Epidemiology and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, with special emphasis on the influence of antibiotic treatment Analysis of 189 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2121-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extended-spectrum cephalosporinases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1766-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of DHA-23, a novel plasmid-mediated and inducible AmpC beta-lactamase from Enterobacteriaceae in Northern Taiwan. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:436.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beta-lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Type I beta-lactamases of Gram-negative bacteria: interactions with beta-lactam antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:792-800.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diverse potential of beta-lactamase inhibitors to induce class I enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:156-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utility of the ceftazidime-imipenem antagonism test (CIAT) to detect and confirm the presence of inducible AmpC beta-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:237-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiple mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: our worst nightmare? Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:634-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antimicrobials. Front Microbiol. 2014;4:422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotics in laboratory medicine (5th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005.

- Occurrence and detection of AmpC beta-lactamases among Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis isolates at a veterans medical center. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1791-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by Kirby-Bauer disc duffusion method. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1973;3:135-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. In: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, CLSI Document M100-S23 (23rd ed). Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:490-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genomic fingerprinting of bacteria using repetitive sequence based polymerase chain reaction. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1994;5:25-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of inducible AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a tertiary care hospital in Northern India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2008;26:89-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic utility of combination of inducer and inhibitor based assay in detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa producing AmpC ß-lactamase. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;87:116-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro antagonism of beta-lactam antibiotics by cefoxitin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21:968-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction of chromosomal beta-lactamases by different concentrations of clavulanic acid in combination with ticarcillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;21:9-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stepwise upregulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal cephalosporinase conferring high-level beta-lactam resistance involves three AmpD homologues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1780-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural and functional characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa global regulator AmpR. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:3890-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Co-existence of Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinase among plasmid encoded CMY-2 harbouring isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in North India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:257-60.

- [Google Scholar]