Translate this page into:

Risk factors for readmission of COVID-19 ICU survivors: A three-year follow up

For correspondence: Dr Laura Velasco Rodrigo, Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Gregorio Maranon National Hospital, 280 07 Madrid, Spain e-mail: laura.velasco13@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Background & objectives

Evidence suggests that individuals who have been hospitalised due to COVID-19 are more susceptible to future mortality and readmission, thereby imposing a substantial strain on their quality of life. The available data on intensive care unit (ICU) survivors, particularly in terms of long-term outcomes, is notably insufficient. This study focused on the long-term outcomes for ICU survivors of COVID-19, specifically readmission and mortality, as well as possible risk factors that could lead to their need for readmission.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational study of 505 individuals admitted to the ICU of a tertiary care hospital between March 2020 and March 2021. Follow up concluded in January 2024. We evaluated the need for hospital and ICU readmissions, examining potential risk factors, including patient comorbidities, clinical situation at the time of the previous hospital and ICU admission, and evolution and treatment in the ICU. As a secondary objective, we determined the prevalence of long-term mortality.

Results

Among 341 ICU survivors, 75 (22%) required hospital readmission, with a median time to readmission of 415 days (IQR: 166–797). The most frequent cause of readmission was respiratory conditions (29.3%). The median hospital stay during readmission was six days. Independent risk factors for hospital readmission included age, elevated creatinine levels at ICU admission, and length of stay in the ICU. Of the 75 readmitted to the hospital, 19 required ICU readmission. Ten individuals died following hospital discharge.

Interpretation & conclusions

Patients requiring ICU admission due to COVID-19 have a significant risk of hospital readmission, particularly those with advanced age, elevated creatinine levels at ICU admission, and longer ICU stays.

Keywords

COVID-19

long-COVID

post-COVID

post-ICU

readmission

severe COVID

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in China in December 2019, the resulting pandemic has profoundly affected Europe. Spain is among the European nations with the highest incidence of diagnosed COVID-19 cases, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection1. During the peak of the pandemic, severe cases of COVID-19 necessitated specialised medical care, leading to the collapse of healthcare systems in several highly developed countries, primarily due to the demand for intensive care units (ICUs) for patient management1.

As the number of COVID-19 survivors has grown, attention has been increasingly focused on the post-acute sequelae and complications like dyspnoea, arthro-myalgia, subacute thrombosis, respiratory failure, and reduced quality of life affecting many patients2-4. These subacute symptoms, commonly referred to as post-COVID syndrome, are particularly prevalent among patients who experience severe illness5. Furthermore, it has been proposed that individuals hospitalised with COVID-19 face an elevated risk of long-term readmission and mortality. However, its precise impact on long-term outcomes remains unclear due to limited evidence, with most research focusing on short- to medium-term outcomes and a few studies addressing patient status beyond six months or one-year post-discharge5-8. Research specifically targeting ICU survivors is particularly scarce despite indications that they may be disproportionately affected by post-acute complications3,5.

While risk factors for post-COVID symptoms are well defined4,9, less is known about the determinants of late hospital readmissions. Hospital readmission rates have become a critical indicator of healthcare quality, given their substantial burden on healthcare systems and their significant negative impact on patients’ health-related quality of life10. Previous studies have suggested that advanced age, comorbidities, and sex (males in particular) may be factors for the increased likelihood of hospital readmission among COVID-19 survivors7,8. However, these factors have not been comprehensively examined in ICU survivors. Identifying high-risk patients for late readmission could inform targeted management and follow up strategies, potentially improving outcomes.

This study aimed to assess long-term mortality and hospital and ICU readmission rates among adult survivors of severe COVID-19. A secondary objective was to analyse risk factors associated with hospital readmissions.

Materials & Methods

Study design

This observational study was conducted at the Gregorio Maranon University Hospital in Madrid, Spain. The hospital’s ethics committee approved the study protocol, which included methods for obtaining informed consent. All individuals consecutively admitted to the ICU for COVID-19 between March 3, 2020, and March 22, 2021, were included. They were followed up prospectively from the moment of their ICU admission up to January 14, 2024. The SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

The physicians determined ICU admission based on disease severity and patients’ pre-COVID life expectancy, age, dependence status, and comorbidities.

Data collection

The baseline clinical data, including comorbidities and chronic medication use, were collected at emergency department admission and verified using electronic medical records of the Community of Madrid. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was used to estimate the study participants’ comorbidities.

According to the established hospital protocol, all symptoms and their respective onsets, axillary temperature, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded on arrival. When the clinical picture suggested COVID-19, an RT-PCR test and a chest X-ray were performed.

We collected information from two laboratory sample sets: (i) obtained upon admission to the emergency room, and (ii) obtained upon admission to the ICU. The laboratory test results were collected as continuous and categorical variables. The limits for categorical variables were established according to the pathological limit of the centre’s laboratory.

The periods from symptom onset to hospital admission and from hospital admission to ICU admission were recorded, so was the ICU length of stay and hospital stay. Treatments to specifically target COVID-19 and supportive care such as renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation, were noted throughout the patient’s hospital stay.

Following hospital discharge, study participants were followed up till January 14, 2024, using electronic health records from the Community of Madrid. We recorded the need for hospital readmission, the duration of the readmission, and its cause. To assess the clinical severity of readmission, we registered the results from two clinical Scales: the Manchester Triage System (MTS) performed on their first evaluation in the emergency department, and the Norton Scoring System (NSS), carried out at the time of admission to the general hospital ward. The Norton Scoring Scale (NSS) evaluates the following health parameters on a Scale from 1 to 5: physical condition, mental condition, activity, mobility, and incontinence, with a cumulative final score ranging from 5 to 20. Although it has not been validated specifically for COVID-19, it has demonstrated its predictive value for complications and mortality in many pathologies in hospitalised patients, where its use is widespread11,12. The MTS is a 5-level triage system commonly used in Europe. This algorithm uses flowcharts describing the signs and symptoms of the patients and divides patients accordingly into five increasing priority levels: blue (non-urgent), green (standard), yellow (urgent), orange (very urgent), and red (immediate). There is extensive literature on MTS, and its validity has been proved in patients with infectious diseases and sepsis13,14. When collecting the MTS results, we included a flowchart, discriminator, and clinical risk classification. We also recorded the appearance of new comorbidities that were not present at the first admission.

Statistical analysis

For their description, continuous variables were expressed with the median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were expressed with frequencies and percentages. For the statistical analysis performed only on ICU survivors, we compared hospital readmission with all the variables related to the patient’s previous history and in-hospital evolution. All relevant risk factors during their previous ICU admission were considered, including demographic parameters, comorbidities, chronic medication, APACHE-II on admission, laboratory test values, received drugs, length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess variable distribution. For addressing the possible risk factors for readmission, we used the Mann Mann-Whitney U test for comparing continuous variables, since they were all found to be non-parametric in distribution. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Finally, logistic regression was performed for factors identified in the univariate analysis, using a significance threshold of P<0.1. IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for all analyses.

Results

We analysed data from 505 consecutive study participants admitted to the ICU from March 4, 2020, to March 22, 2021, with severe COVID-19. Of these, 164 (32.5%) died in the ICU. The demographic characteristics and comorbidities of the ICU survivors have been shown in table I. The median age was 60 yr (IQR: 50–68), with a predominance of males (68.9%) and most having a body mass index (BMI) above 25 Kg/m2 (84.8%). The common comorbidities were hypertension (44.6%) and dyslipidaemia (43.7%).

| ICU survivors (n=341) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60 (50-68) |

| Male sex | 235 (68.9%) |

| BMI >25 kg/m2 | 289 (84.8%) |

| Charlson Index | 1 (0-2) |

| Arterial hypertension | 152 (44.6%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 149 (43.7%) |

| Insulin-dependent diabetes | 19 (5.6%) |

| Non-insulin- dependent diabetes | 53 (15.5%) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 86 (25.2%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 16 (4.7%) |

| Arrhythmias | 23 (6.7%) |

| Cardiac surgery | 3 (0.9%) |

| Any respiratory disease | 77 (22.6%) |

| COPD | 15 (4.4%) |

| Asthma | 29 (8.5%) |

| OSA | 28 (8.2%) |

| Pulmonary surgery | 3 (0.9%) |

| Other respiratory diseases | 10 (2.9%) |

| HIV | 6 (1.8%) |

| Inmunosuppression | 36 (10.6%) |

| Cancer | 33 (9.7%) |

| Chronic renal failure | 29 (8.5%) |

| Dialysis | 1 (0.3%) |

| Brain stroke | 12 (3.5%) |

| Hepatopathy | 25 (7.3%) |

| Arterial insufficiency | 7 (2.1%) |

| Treatment with ACEIs/ARB | 121 (35.5%) |

| Antihypertensive drugs other than ACEIs/ARBs | 78 (22.9%) |

| Treatment with bronchodilators | 39 (11.4%) |

Data are expressed as medians (Interquartile range) or as frequencies and percentages as appropriate. Cardiovascular disease includes valvopathies, arrhythmias, heart failure and ischemic heart disease. BMI, body mass index; ACEIs/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICU, intensive care unit

The median time from symptom onset to hospital admission was six days (IQR: 4–8), and from hospital to ICU admission was three days (IQR: 1-5). The most common symptom in the emergency department was fever (85%). Most of these study participants (82.1%) exhibited a bilateral infiltrate on the first chest X-ray performed upon hospital admission. The median NSS on admission was 15 (IR: 11-18).

Table II provides a summary of the treatment course and outcomes observed in the ICU. The median ICU length of stay was 14 days (IQR: 8-33.5). During this period, nearly 60 per cent of study participants required mechanical ventilation, with a median duration of 20 days (IQR: 11–44).

| ICU stay (n=341) | |

|---|---|

| Time from hospital admission to ICU admission | 3 (1-5) |

| Length of stay in ICU (days) | 14 (8-33.5) |

| Required mechanical ventilation, no. (%) | 198 (58.1%) |

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (days) | 20 (11-44) |

| APACHE II on admission | 11 (7-18) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 134 (39.3%) |

| Remdesivir | 95 (27.9%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 133 (39%) |

| Azithromycin | 79 (23.2%) |

| Ceftriaxone | 236 (69.2%) |

| Tocilizumab | 180 (52.8%) |

| Corticosteroids | 317 (93%) |

| Pronation | 181 (53.1%) |

| Neuromuscular relaxants | 107 (31.4%) |

| Nitric oxide | 10 (2.9%) |

| Dialysis | 11 (3.2%) |

| Tracheostomy | 105 (30.8%) |

Data are expressed as medians (Interquartile range) or as frequencies and percentages as appropriate. APACHE II, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II

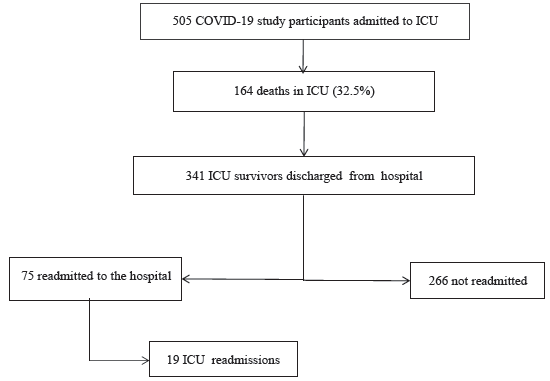

Among the study participants who survived their ICU stay, 22 per cent (n=75) required readmission following their initial hospital discharge. The median follow up period was 1,154 days (IQR: 1,054–1,252 days), equating to more than three years. Figure presents a detailed flowchart illustrating study participants readmission.

- Flowchart of study participants’ readmission. ICU, intensive care unit.

The median time to hospital readmission was 415 days (IQR: 166–797). Most of the readmissions, 54 study participants (72%), were classified as urgent. According to the MTS performed in the emergency department, more than 50 per cent of these study participants were assigned third-level priority (urgent, yellow), while 22.2 per cent were classified as having higher clinical risk (very urgent or immediate priority). The full classification is presented in supplementary table I. The most common presenting complaint, according to the MTS flowchart, was ‘unwell adult’ (Supplementary Table II).

Table III outlines the causes of hospital readmission, with respiratory conditions being the most frequent (29.3%). The median length of stay during readmission was six days (IQR: 3-11). The median NSS at the time of readmission was 19 (IQR: 16-20). Only 13 study participants (17.3%) developed new comorbidities not documented during their initial admission (described in Supplementary Table III).

| Causes of hospital readmission (n=75) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | 22 (29.3%) |

| Cardiovascular | 6 (8%) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 4 (5.3%) |

| Infection | 16 (21.3%) |

| Oncologic | 6 (8%) |

| Haemorrhage | 5 (6.7%) |

| Other | 16 (21.3%) |

| Causes of ICU readmission (n=19) | |

| Respiratory | 12 (63.2%) |

| Cardiovascular | 3 (15.8%) |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 0 (0%) |

| Infection | 1 (5.3%) |

| Oncologic | 0 (0%) |

| Haemorrhage | 3 (15.8%) |

Data are expressed as frequencies and percentages

Table IV compares the characteristics of study participants who were readmitted to the hospital with those who were not. Study participants requiring readmission were older and had a higher prevalence of comorbidities, including diabetes, dyslipidaemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and a history of cancer. During ICU admission, these study participants exhibited higher creatinine levels, lower PaO2/FiO2 ratios, and lower troponin-I levels. Additionally, they more frequently required mechanical ventilation and had longer stays in both the ICU and the hospital.

| Readmitted (n=75) | Not readmitted (n=266) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 64 (54–71) | 60 (49–67) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes | 25 (33.3%) | 46 (17.3%) | 0.04 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 44 (58.7%) | 105 (39.5%) | 0.004 |

| Oncologic history | 14 (18.7%) | 19 (7.1%) | 0.007 |

| COPD | 7 (9.3%) | 8 (3%) | 0.027 |

| Immunosuppression | 14 (18.7%) | 22 (8.3%) | 0.017 |

| Peripheral arteriopathy | 6 (8%) | 1 (0.4%) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Index = 0 | 23 (30.7%) | 143 (53.8%) | <0.001 |

| Use of mechanical ventilation during ICU stay | 52 (69.3%) | 146 (54.9%) | 0.034 |

| Blood tests obtained at the time of hospital admission | |||

| D-Dimer (ng/ml)* | 348 (230–648) | 269 (175–449) | <0.001 |

| Lactate (mmol/l)* | 1.7 (1.23–2.2) | 2 (1.4–2.55) | 0.032 |

| CRP > 0.5 mg/dl | 62 (82.7%) | 336 (89.5%) | 0.039 |

| Lymphopenia (<500/mcl) | 46 (61.3%) | 209 (78.6%) | 0.004 |

| Blood tests obtained at the time of ICU admission | |||

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl)* | 769 (658–917) | 720 (612–854) | 0.035 |

| Creatinine>1.2 mg/dl | 18 (24%) | 30 (11.3%) | 0.08 |

| Creatinine (mg(dl)* | 0.76 (0.6–1.19) | 0.71 (0.57–0.9) | 0.025 |

| Cardiac troponin I (ng/dl)* | 7.2 (2.6–29.4) | 13.4 (6–43.8) | 0.031 |

| paO2 <80mmHg | 22 (29.3%) | 105 (39.5%) | <0.001 |

| paO2/FiO2* | 90 (71–121) | 114 (75–156) | 0.034 |

| Length of ICU stay | 21 (11–44) | 13 (7–29) | 0.002 |

| Length of hospital stay | 39.5 (27–90.25) | 29 (19–59.25) | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as medians (Interquartile range) or as frequencies and percentages as appropriate. *indicates continuous variables. CRP; C reactive protein

Multivariate analysis identified three factors independently associated with hospital readmission: advanced age, elevated creatinine levels (greater than 1.2 mg/dl) at ICU admission, and prolonged ICU stay. These findings have been summarized in supplementary table IV.

Of the 75 study participants readmitted to the hospital, 19 required subsequent ICU readmission. The causes for ICU readmission have been detailed in table III, with respiratory issues being the predominant reason (63.2%).

Ten study participants died following their initial hospital discharge, nine of whom passed away during their hospital readmission. The median time from discharge to death was 794 days (IQR: 386–965). Respiratory failure was identified as the cause of death in four study participants, two of whom had residual fibrosis from a prior COVID-19 infection, which was considered an intermediate cause of death. Three study participants died from complications associated with stage IV oncologic disease, one from haemorrhagic shock secondary to ruptured oesophageal varices, and one during aortic valve replacement surgery. For one study participants, the cause of death could not be determined.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we observed a high hospital readmission rate (22%) among survivors of severe COVID-19 infection over a three-year follow up period. Readmission was independently associated with advanced age, elevated creatinine levels at ICU admission, and prolonged ICU length of stay. The predominant cause of urgent readmissions was respiratory, likely reflecting impaired pulmonary function, as most patients did not have pre-existing respiratory co-morbidities. However, long-term ICU readmission and mortality rates were relatively low (5.6% and 2.3%, respectively), with only a few deaths directly attributable to COVID-19. These findings, in conjunction with other reports on the long-term sequelae of COVID-192,5, underscore the chronic nature of a disease that is highly lethal in its acute phase.

Patients who recover from COVID-19, particularly ICU survivors, face significant long-term impacts on their quality of life due to physical, psychological, and social sequelae, which increase their risk of hospital readmission. Consequently, understanding the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and identifying risk factors for unplanned hospital readmissions are essential, particularly as the number of survivors continues to grow. While considerable research has focused on readmission risk prediction tools for COVID-19 patients, their efficacy remains uncertain, and few studies specifically target ICU survivors7,8,15,16.

The NSS evaluates the following parameters on a scale from 1 to 5: physical condition, mental condition, activity, mobility, and incontinence. Although initially conceived as a pressure ulcer risk prediction scale, it has long been established as a prognostic scale for hospitalised patients, with its score being associated with the risk of complications and mortality11,17. In our study, readmitted study participants had a median NSS of 19 (IQR: 16-20), compared to a median of 15 (IQR: 11-18) during their initial admission, indicating that the severity of readmissions was lower. Nevertheless, a significant proportion of these study participants required ICU readmission.

Our observed readmission rate (22%) exceeds those reported in other Spanish and international studies, which average around 10 per cent18-20. However, these studies focused on less than one month follow up periods, and readmission rates rise markedly with longer follow up durations7,8. In international studies with follow up periods exceeding one month, such as those by Günster et al21 and Donnelly et al22 readmission rates similarly exceeded 20 per cent, consistent with our findings. Notably, none of these studies specifically examined ICU survivors, a population with a higher prevalence of sequelae3,5. Our extended follow up period of over three years revealed a median time to readmission of 415 days, emphasising the importance of conducting studies beyond one year from ICU discharge.

The risk factors for readmission identified in our study were age, elevated creatinine levels, and prolonged ICU stay. These factors were aligned with the findings from studies on hospital survivors over shorter follow up periods. Age, a critical determinant of COVID-19 severity and mortality1,23-25, is also associated with slower recovery of functionality after hospitalisation and a reduced capacity to adapt to disease sequelae. Previous studies have identified age as a predisposing factor for symptom chronification15,26. For instance, Mooney et al27 observed a nearly two-fold increase in readmission rates among older patients, while Günster et al21 and Verna et al28 reported higher risks among individuals over 80 and 60 yr, respectively.

Renal involvement is frequently observed in COVID-19, with acute kidney injury (AKI) occurring in an estimated 3–5 per cent of hospitalised patients29,30. Among critically ill patients, up to 30 per cent experience grade II–III acute renal failure according to AKI classifications1,25,31. AKI is associated with disease severity, increased risk of ICU admission, and mortality32. Verna et al28 identified AKI at hospital admission as a risk factor for rehospitalisation among COVID-19 survivors. Similarly, Yeo et al33 and Nematshahi et al 34 reported that peak serum creatinine levels ≥1.29 mg/dl and 1.2 mg/dl, respectively, during hospitalisation, more than doubled the risk of readmission.

The reason for the association between increased creatinine levels and readmission remains unclear. We consider that renal dysfunction may be both a consequence and marker of a proinflammatory systemic state. Patients with acute renal failure likely present more extensive disease associated with inflammation and immunosuppression and, therefore, present multiorgan complications and a prolonged recovery, incrementing their risk of readmission28,33,34.

ICU length of stay has not been widely evaluated as a predisposing factor for readmission, as most studies have not specifically focused on ICU populations. The relationship between hospital length of stay and readmission remains contentious. While studies with follow up periods shorter than one month, such as that by Parra et al18 associated shorter hospital stays with higher readmission risk, in studies with a longer follow up, the risk was inverted35. One potential explanation is that short-term readmissions often result from acute complications of the disease that were not identified at the time of the initial hospital discharge. In contrast, long-term readmissions, not captured in studies with limited follow up periods, could encompass hospitalisations arising from the sequelae and prolonged consequences of the infection. Symptoms of post-COVID syndrome, which can persist beyond one year after infection, likely contribute to long-term hospitalisation needs.

Prior studies identified comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and immunosuppression as potential risk factors for readmission7,8,28. In our study, the group of readmitted study participants presented more frequently with arterial hypertension, diabetes, immunosuppression, dyslipidaemia, COPD, and a Charlson Index greater than 0. However, these factors did not attain statistical significance in our logistic regression analysis, likely due to the limited sample size. Further investigations with larger cohorts of ICU survivors are necessary to validate these findings.

Despite the strengths of this study, various limitations must be acknowledged, which may impact the interpretation and generalisability of the findings. Firstly, this study was conducted at a single centre in Spain, which might have specific diagnostic and therapeutic practices. Previous research highlighted that healthcare system characteristics could influence readmission rates7,20,21. The findings from a public hospital within the Spanish healthcare system might differ from those observed in countries where private healthcare systems predominate.

Secondly, the study participants included in this study were treated in 2020 and 2021, when therapeutic approaches to COVID-19 differed from those subsequently recommended. Moreover, vaccination was not yet available during the data collection period. While these factors may limit the extrapolation of these findings to the current context, our data suggest that the treatment regimens employed at the time had minimal impact on post-COVID readmissions. Nonetheless, these results remain valuable for understanding outcomes in COVID-19 survivors admitted to the ICU before 2021.

Thirdly, data on readmissions were extracted from medical records within the Community of Madrid. Admissions to hospitals in other regions might have been missed. However, we consider such cases to be improbable and unlikely to affect the conclusions significantly.

Lastly, distinguishing between individuals hospitalised due to the long-term consequences of COVID-19 and those with COVID-19 who were admitted for unrelated reasons is inherently challenging. Despite this, the observed readmission rate far exceeds both the expected risk in the general population and the historical risk associated with other respiratory infections15, supporting a causal relationship between COVID-19 and hospital readmission.

In conclusion, patients requiring ICU admission for COVID-19 are frequently readmitted after their initial hospital discharge. Future research should include experimental studies aimed at mitigating the dominant risk factors and extending data collection to multi-centre populations to enhance the generalisability of findings. Our study highlighted the substantial long-term burden faced by survivors of severe COVID-19, particularly those requiring ICU admission. The observed hospital readmission rate underscored the critical need for continued post-discharge care and monitoring, especially for patients with advanced age, renal dysfunction, and prolonged ICU stays, which were identified as independent risk factors. These findings emphasise the importance of tailoring follow up strategies to mitigate the chronic impact of COVID-19 and improve long-term outcomes. Further research is warranted to explore interventions that could reduce readmissions and enhance recovery for this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgment

The present study was undertaken as the part of the doctoral programme by the first author (EC) at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), Madrid, Spain.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, EC, upon reasonable request.

Financial support & sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- [Características, evolución clínica y factores asociados a la mortalidad en UCI de los pacientes críticos infectados por SARS-CoV-2 en España: studio prospectivo, de cohorte y multicéntrico] Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67:425-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Four-Month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:1525-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Post intensive care syndrome in survivors of critical illness related to coronavirus disease 2019: Cohort study from a New York city critical care recovery clinic. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1427-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic factors for deterioration of quality of life one year after admission to ICU for severe SARS-COV2 infection. Qual Life Res. 2024;33:123-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes among patients with 1-Year survival following intensive care unit treatment for COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;327:559-65.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 post-acute sequelae among adults: 12-month mortality risk. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:778434.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital readmissions and emergency department re-presentation of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2022;46:e142.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review on COVID-19 readmission and risk factors: Future of machine learning in COVID-19 readmission studies. Front Public Health. 2022;10:898254.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- [Calidad de vida y síntomas persistentes tras hospitalización por COVID-19. Estudio observacional prospectivo comparando pacientes con o sin ingreso en UCI] Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2022;69:326-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable: A systematic review. CMAJ. 2011;183:E391-402.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The norton scale is an important predictor of in-hospital mortality in internal medicine patients. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:1947-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Low Norton scale score predicts worse outcomes for Parkinson’s disease patients hospitalized due to infection. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2015;1:2333721415608139.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Triage of patients with fever: The Manchester triage system’s predictive validity for sepsis or septic shock and seven-day mortality. J Crit Care. 2020;59:63-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audit of a computerized version of the Manchester triage system and a SIRS-based system for the detection of sepsis at triage in the emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15:67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Post-covid syndrome in individuals admitted to hospital with covid-19: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ2021. ;372:n693.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A safe protocol to identify low-risk patients with COVID-19 pneumonia for outpatient management. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:1663-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Norton scale, hospitalization length, complications, and mortality in elderly patients admitted to internal medicine departments. Gerontology. 2013;59:507-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital readmissions of discharged patients with COVID-19. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:1359-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of hospital readmissions of COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13733.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of risk factors on readmission cases of COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea: Using nationwide health claims data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5844.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- 6-month mortality and readmissions of hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A nationwide cohort study of 8,679 patients in Germany. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255427.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Readmission and death after initial hospital discharge among patients with COVID-19 in a large multihospital system. JAMA. 2021;325:304-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics and day-90 outcomes of 4244 critically ill adults with COVID-19: A prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:60-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: A prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:e9-611.

- [Google Scholar]

- 110 A single centre study on the thirty-day hospital reattendance and readmission of older patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Age Ageing. 2021;50:i12-42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with readmission in the United States following hospitalization with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:1713-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The involvement of chronic kidney disease and acute kidney injury in disease severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19: A meta-Analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2021;46:17-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Patients with COVID-19 in 19 ICUs in Wuhan, China: A cross-sectional study. Crit Care. 2020;24:219.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e16-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of thirty‐day readmission rate, timing, causes and predictors after hospitalization with COVID‐19. J Intern Med. 2021;290:157.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Factors predicting readmission in patients with COVID-19. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14:374.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Longer length of stay, days between discharge/first readmission, and pulmonary involvement ≥50% increase prevalence of admissions in ICU in unplanned readmissions after COVID-19 hospitalizations. J Med Virol. 2022;94:3750-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]