Translate this page into:

Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst the community dwelling rural older adults in northern India

Reprint requests: Dr S.C. Tiwari, Professor & Head, Department of Geriatric Mental Health, King George's Medical University, Lucknow 226 003, India e-mail: sarvada1953@gmail.com, sarvada1953@rediffmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The population of elderly is growing globally and so are the physical illnesses and psychiatric morbidity. This study was planned to assess the prevalence and patterns of psychiatric morbidity amongst rural older adults in Lucknow, north India.

Methods:

A survey was conducted in subjects aged 60 yr and above to identify the cases of psychiatric morbidity in rural population from randomly selected two revenue blocks of Lucknow district, Uttar Pradesh, India. All subjects were screened through Hindi Mental Status Examination (HMSE) and Survey Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (SPAS) to identify for the suspected cases of cognitive and the psychiatric disorders, respectively. The subjects screened positive on HMSE and SPAS were assessed in detail on Cambridge Mental Disorder of the Elderly Examination-Revised (CAMDEX-R) and Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), to diagnose cognitive disorders and psychiatric disorders (other than the cognitive), respectively on the basis of International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) diagnostic guidelines.

Results:

The overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in rural older adults was found to be 23.7 per cent (95% CI=21.89-25.53). Mood (affective) disorders were the commonest (7.6%, 95% CI=6.51-8.80), followed by mild cognitive impairment (4.6%, 95% CI=3.72-5.53), mental and behavioural disorders due to substance use (4.0%, 95% CI=3.17-4.87) and dementia (2.8%) [Alzheimer's disease (2.4%, 95% CI=1.81-3.16) and vascular (0.4%, 95% CI=0.16-0.73)].

Interpretation & conclusions:

Overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst rural elderly in this study was found to be less in comparison to those reported in earlier studies from India. However, prevalence pattern of different disorders was found to be similar. Therefore, it appears that a stringent methodology, refined case criteria for diagnosis and assessment by trained professionals restrict false diagnosis.

Keywords

Aged

CAMDEX-R

cognitive disorders

dementia

epidemiology

HMSE

mood disorders

northern India

prevalence

The population of elderly is growing rapidly with the increase in life expectancy. Besides physical illnesses, psychiatric morbidity is also commonly seen in older adults. Hence, the burden of caregivers and health care professionals is increasing day by day1. The proportion of older adults in less developed countries is rising much faster than in developed countries2. The life expectancy of an average Indian has increased from 36.7 in 1951 to over 67.14 in 20123. Also, the population of older adults (≥60 yr) in India increased to 102 millions in 20114. The proportion of elderly persons in India rose from 5.3 per cent in 1961 to 7.5 per cent in 2001, and was currently 8.4 per cent in 20114.

Many epidemiological studies have been conducted in India to estimate the psychiatric morbidity in general population567 but only a few have taken specifically the elderly population into consideration89101112.

A couple of studies were conducted in institutional and hospital settings where prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in older adults was found to be 49.28 per cent10 and 8.6 per cent in the geriatric population13. A study conducted by Tiwari8, almost a decade ago using International Classification of Diseases-9 (ICD-9) diagnostic criteria, reported 43.32 per cent psychiatric morbidity in rural elderly. Another study11 reported a prevalence of 49.2 per cent in New Delhi (Urban), and 19.3 per cent prevalence was reported in a Lucknow based study12 in the urban elderly population.

Some of the community-based studies have focused only on specific disorders like depression or dementia in the elderly population. A study14 reported 31 per cent prevalence of depression in elderly population aged 60 years and above. Another study15 found 12.7 per cent prevalence of depression in the elderly. Shaji et al16 reported 3.36 per cent dementia in elderly aged of 65 yr and above in urban areas of southern India. From rural south India, a study reported dementia prevalence to be 3.4 per cent in elderly population15.

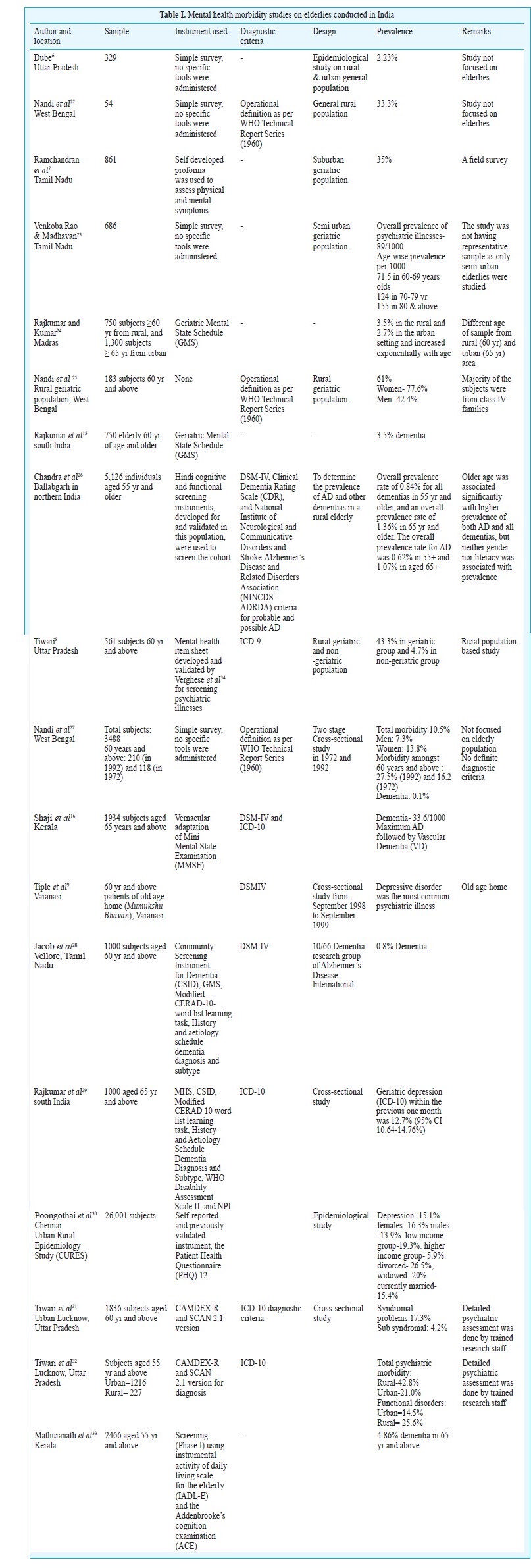

Although prevalence figures are available for developed regions of the world including Europe17, North America181920, and Japan21; but this information is largely missing for developing countries. A brief review of the prevalence and incidence studies conducted in India revealed highly variable results because of the differences in settings, sampling process, type of tools used, and methods of ascertaining diagnosis (Table I).

This study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst the community dwelling rural elderly aged 60 yr and above in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, north India.

Material & Methods

Sample size: The two rural revenue blocks-Malihabad and Bakshi Ka Talab of Lucknow district of the State of Uttar Pradesh in north India were randomly selected for the study location. There were 215 villages in these two rural blocks with approximate population of 4,52,598 and 300 to 500 houses in each village. Of these, 30 villages were randomly selected for the complete enumeration of the elderly aged 60 yr and above. This study was conducted during 2008 to 2010. Assuming a prevalence of 43.3 per cent of psychiatric morbidity in rural elderly8 and a precision of 2.5 per cent, the required sample size was calculated to be 2060 subjects.

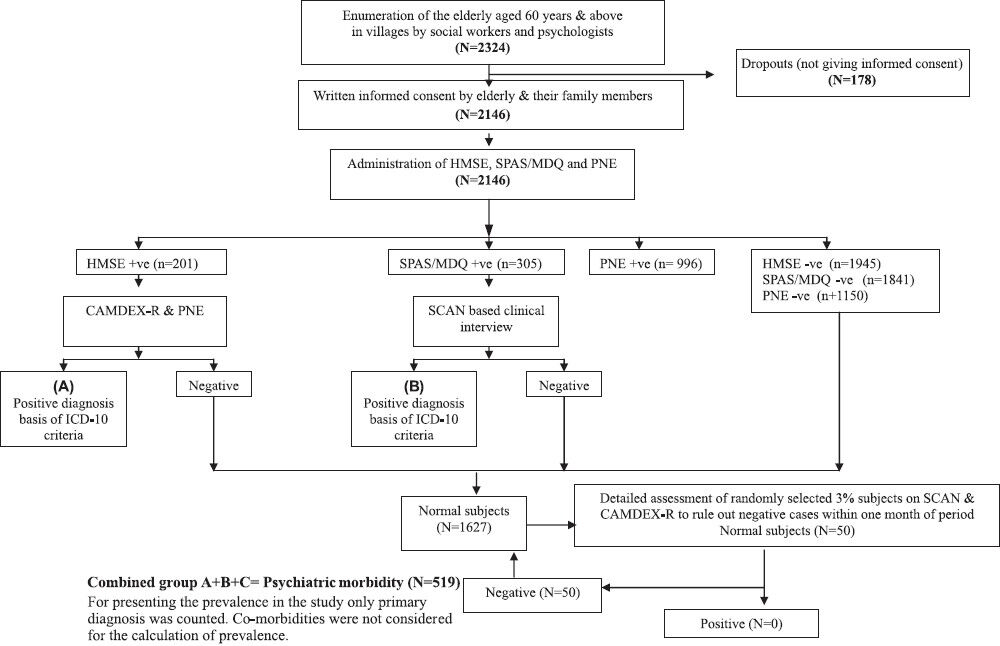

A total of 2324 individuals aged ≥60 yr were included in the study. Of them, 178 refused to participate in the study. Thus, the study sample consisted of 2146 subjects (Figure). Written informed consent was obtained from all.

- Flow chart of the study procedure. HMSE, Hindi Mental State Examination; SPAS, Survey Psychiatric Assessment Schedule; MDQ, Mood Disorder Questionnaire; PNE, Physical and Neurological Examination; SCAN, Schedule for Clinical Assessment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders; CAMDEX-R, Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly - Revised.

Study was approved by institutional ethical committee, King George's Medical University, UP, Lucknow.

Inclusion criteria: (i) Older adults (both males and females) aged 60 yr and above with age confirmation by an authentic document/certificate. (ii) Self & family assessment of the subject.

Any elderly with problems with speech, hearing and vision, which could impede the interview was excluded.

Tools used: Hindi translated versions of the standardized English tools were used in the study. The tools consisted of:

(i) Semi structured proforma for bio-socio-cultural information and other relevant family details (Socio-demographic proforma i.e. SDP).

(ii) Socio-economic status scale (SES)35: There are seven profiles in the scale to calculate the SES of a family. These profiles are: 1- House, 2- Material possessions, 3- Education, 4- Occupation, 5- Economic, 6- Possessed land/House cost, and 7- Social profile. On SES scale maximum score can be obtained 70 (10 scores in each profile). The scale is equally good to assess SES of urban and rural families. Cut-off scores 0-25.5 for lower; 25.6-47.5 for middle; and 47.6-70 for upper SES groups.

(iii) Hindi Mental Status Examination (HMSE)36: This scale was developed specifically to counter the education and language bias while screening rural illiterate elderly people for cognitive impairment in India. A cut-off score of 24 was considered on HMSE for identification of suspects or cases of cognitive impairment.

(iv) Survey Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (SPAS)37 and Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ)38: SPAS consists of 51 items divided into three sections: (1) organic disorders, (2) affective disorders/psychoneurosis, and (3) schizophrenia/paranoid disorders. For identification of ‘cases’ each section of SPAS was scored independently as given below:

Section-1: A simple additive score of the 12 responses classified the subjects as ‘suspects’ in different categories. The following cut-off points were used: No organic disorder - 9-12, Mild organic disorder- 7-8, and Severe organic disorder- 0-6.

Section-2: The 44 responses were summed up and the following cut-off points were used to identify ‘suspected cases’ and ‘non cases’: ‘Non case’- 0-10, and ‘Case’- 11-65.

Section-3: In this section any positive answer indicated possible case.

However, in this study, SPAS was used as screening instrument to identify suspects for neuropsychiatric disorders. Subjects found positive on one or more than one sections using the above cut-off score and/or MDQ positive subjects (cut-off=7) were considered as SPAS+ve. MDQ was used as a safeguard against ‘false negative’ classification of possible mood disorder cases on SPAS.

(v) Schedule for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) 2.1 version39: Positive symptoms on SCAN based clinical interview were used to make diagnosis according to ICD-10 criteria40 in the study.

(vi) Cambridge Examination for Mental Disorders of the Elderly - Revised (CAMDEX-R)41: CAMDEX-R consists of eight sections for complete assessment of an older adults: Section A- Clinical information about current condition, past history and family history of the patient; B-Cognitive function Cambridge cognitive (CAMCOG); C- Interviewer's observation on the patients appearance and behaviour; D- Physical and neurological examination; E- Results of laboratory tests; F- Medication received by the patient; G- Additional information; H- Structured interview with the relative/caregiver. Inter-rater reliability of the CAMDEX ranged from 0.83 to 0.94 for the patient interview.

It also gives diagnosis based on the criteria of ICD-10 and Diagnostic and Statistical Mannual of Mental Disorders - 4th Edition (DSM-4).

(vii) Physical and Neurological Examination (PNE)

Procedure of translation of the tools: Three translators well versed in English and Hindi, translated the original English versions of SPAS37 and CAMDEX-R41 into Hindi independently and then discussed and compared the translation item by item to agree upon a pre-final translated Hindi version (PFHV) of the tools preserving the originality of the items. PFHV tools were administered to 10 literate and 10 illiterate persons aged 60 yr and above, drawn from another community to know the comprehensibility of the items. The final translated Hindi versions (FHVs) of the tools were validated by three bilingual mental health professionals.

Training of the research staff: Clinical psychologist, psychologists, social workers and Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) graduates were involved in data collection. They were appropriately trained. Clinical psychologist was trained for SCAN based clinical interview and for administration of CAMDEX-R (Except PNE section). BAMS graduates were trained to conduct PNE, clinical psychologist, psychologists and social workers were trained to administer HMSE, SPAS/MDQ, SES and for socio-demographic data collection.

Study procedure: All subjects had initial screening through HMSE and SPAS/MDQ to identify ‘probable cases’ for cognitive and neuropsychiatric disorders, respectively. The screened positive subjects on HMSE and SPAS/MDQ were assessed in detail on CAMDEX-R, SPAS/MDQ and SCAN, to diagnose cognitive disorders, and psychiatric disorders other than cognitive disorders, respectively. The included subjects were seen for comprehensive physical and neurological examination.

Three per cent of the total subjects who were found negative on HMSE/SPAS were administered CAMDEX-R for cognitive disorders and SCAN for neuropsychiatric disorders other than cognitive disorders to rule out false negative cases. These assessments were done within one month period. None of these subjects had a symptom profile to lead to a diagnosis. Following this, the older adults were categorized as per their mental and physical health status in different categories. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was diagnosed in individuals who had cognitive impairments beyond that expected for their age and education, but that did not interfere significantly with their daily activities42.

Statistical analyses: The inter-rater reliability between clinical psychologists for administering the CAMDEX-R and SCAN based clinical interview and trainer yielded a positive correlation between 0.71 to 0.83. Between psychologists and trainer it was found 0.78 to 0.92 for administering SPAS/MDQ and HMSE.

All included subjects were categorized into two broad categories on the basis of screening and detailed assessments, i.e. Normal (screen negatives and SCAN and/or CAMDEX-R negative) and psychiatric morbidity group (SCAN and/or CAMDEX-R positive). Three per cent of the normal subjects were reassessed in detail on CAMDEX-R and SCAN to see for false negative cases within one month of the assessment. None of these subjects had enough symptoms to qualify for a diagnosis. The cases with primary diagnosis only were included to calculate the prevalence. Co-morbid psychiatric disorders were not included in the calculation of prevalence. Calculations of confidence interval (CI) for the prevalence and lower and upper limits of the CI explain that the prevalence of disorder lies between these limits for a population. Only point prevalence in this cross-sectional study is presented here. Thus, screened positive cases (not meeting diagnostic levels) were not included to calculate the prevalence.

Results

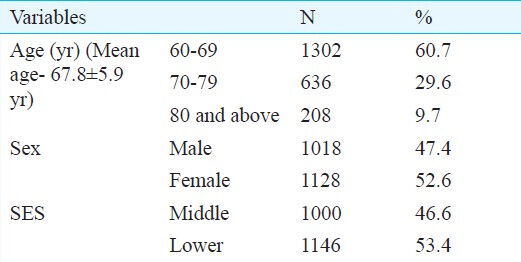

Table II shows age, sex and socio-economic status distribution of study subjects (N=2146). There were more females (52.6%) than males (47.4%). More subjects belonged to lower SES (53.4%) in comparison to middle SES (46.6%). There was no subject from upper SES.

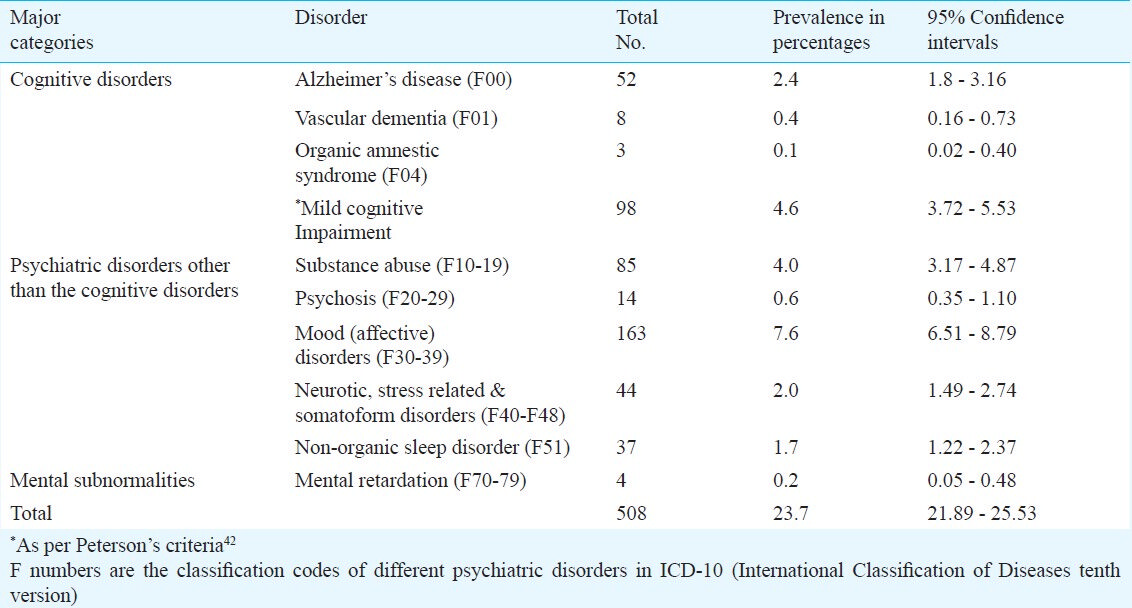

The overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity was found to be 23.7 per cent (508/2146) (95% CI=21.89-25.53) in the rural older adults, of which mood (affective) disorders was the commonest (7.6%, 95% CI=6.51-8.80), followed by mild cognitive impairment (4.6%, 95% CI=3.72-5.53), behavioural and mental disorders due to substance abuse (4.0, at 95% CI=3.71-4.87), dementia (2.8%) [Alzheimer's disease (2.4%, 95% CI=1.81-3.16) and vascular (0.4%, 95% CI=0.16-0.73)], neurotic, stress related and somatoform disorders (2.0%, 95% CI=1.49-2.74), sleep disorders (1.7, 95% CI=1.22-2.37), psychoses (0.6%, 95% CI= 0.35-1.10), organic amnestic syndrome (0.1%, 95% CI=0.02-0.40) and mental retardation (0.2%, 95% CI=0.05-0.48) (Table III).

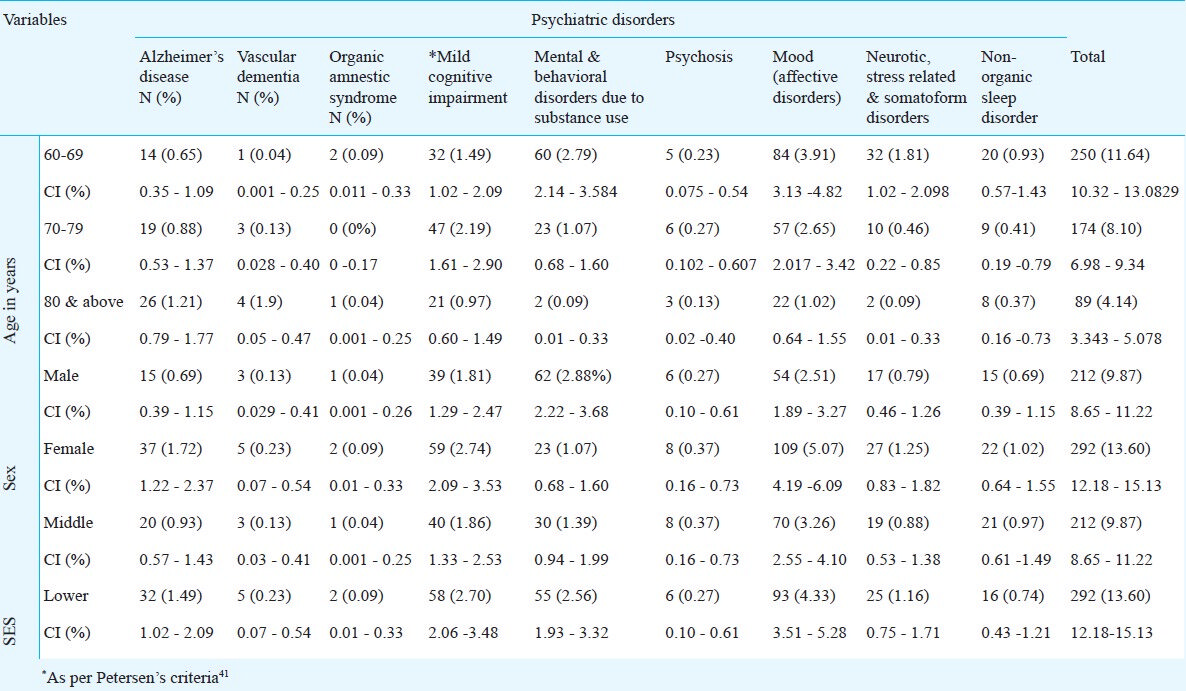

Table IV shows age, sex and SES-wise prevalence of psychiatric morbidities (excluding mental retardation) amongst rural elderlies aged 60 yr and above. Total psychiatric morbidity was found to be higher in the age group of 60-69 yr (11.6%, 95% CI=10.32-13.08) than 70-79 yr (8.1%, 95% CI=6.98-9.34) and 80 yr and above (4.1%, 95% CI=3.34-5.08). However, prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (60-69 yr: 0.65%, 70-79 yr: 0.88%, and >80 yr: 1.2%) and vascular (60-69 yr: 0.04%, 70-79 yr: 0.13%, and ≥80 yr: 1.9%) dementia was found to be increasing with advancing age.

Overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity was found to be more amongst females (13.6%, 95% CI= 12.18-15.13) than males (9.9%, 95% CI=8.65-11.22). Similar pattern was observed for prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (females: 1.72%, 95% CI= 1.22-2.37 and males: 0.69%, 95% CI= 0.39-1.15) and vascular (females: 0.23%, 95% CI= 0.07-0.54 and males: 0.13%, 95% CI= 0.03-0.41) dementia, mild cognitive impairment (females: 2.74%, 95% CI= 2.09-3.53 and males: 1.81%, 95% CI=1.29-2.47), psychosis (females: 0.37%, 95% CI= 0.16-0.73 and males: 0.27%, 95% CI= 0.10-0.61), mood (affective) disorders (females: 5.07%, 95% CI=4.19-6.09 and males: 2.51%, 95% CI= 1.89-3.27), neurotic, stress related and somatoform disorders (females: 1.2%, 95% CI= 0.83-1.82 and males: 0.79%, 95% CI= 0.46-1.26) and non-organic sleep disorder (females: 1.02%, 95% CI= 0.64-1.55 and males: 0.69%, 95% CI=0.39-1.15) except mental and behavioural disorders due to substance use (females: 1.07%, 95% CI= 0.68-1.60 and males: 2.88%, 95% CI= 2.22-3.68).

Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst elderlies belonging to lower SES (13.6%, 95% CI=12.18-15.13) was found to be higher than middle SES (9.9%, 95% CI=8.65-11.22). This pattern was found similar for all other disorders except non organic sleep disorders (lower SES: 0.74%, 95% CI=0.43-1.21; middle SES: 1.97%, 95% CI= 0.61-1.49). Mood (affective) disorders were more prevalent amongst elderlies belonging to lower SES (4.33%, 95% CI=3.51-5.28) compared to middle SES (3.26%, 95% CI=2.55-4.1).

Discussion

The present study attempted to find out the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity in the community dwelling older adults in the rural northern India. Overall psychiatric morbidity in the present study amongst the rural older adults aged 60 yr and above was found to be 23.6 per cent which is less than reported in other studies (27.5 to 43.3%) in rural areas78252732 and in urban areas (13.0 to 49.2%)1112. The reason for this variation might be due to the use of different tools and different diagnostic guidelines for ascertaining the diagnosis. Tiwari8, and Chowdhury and Rasania11 used ICD-9 and DSM III, respectively. In the present study ICD-10 was used. Though Tiwari et al32 reported high prevalence (42.8%) using ICD-10 diagnostic criteria in rural area but they added co-morbidities also to calculate the prevalence. The sample size of this study was small and study subjects were aged 55 yr and above in comparison to present study.

Mood (affective) disorders were found to be the commonest diagnosis. Depression was found to be the most prevalent disorder amongst them in the study. Similar findings have been reported by others92930. Mild cognitive impairment was the second highest problem followed by mental and behavioural disorders due to substance abuse and dementia. For substance use disorders one epidemiological study in India on elderly8 reported slightly higher prevalence (4.5%) than this study. Shaji et al16 reported dementia in 3.4 per cent of elderly population (60 yr and above) in rural population of south India15. In other Indian studies prevalence of dementia has been reported 0.1 per cent in West Bengal27; 4.9 per cent in Kerala33 and 0.8 per cent in Vellore28. The variability in the prevalence of dementia in India may be due to sample size, age of the subjects, instruments used for assessment and diagnostic criteria.

Prevalence of psychosis (0.6%) in the present study was almost equal to that reported by Tiwari8 (0.5%). In the study 1.7 per cent rural older adults had sleep disorder and 0.2 per cent were found to have mild mental retardation. Almost similar prevalence of mental retardation (0.3%) amongst rural older adults was reported earlier9.

Age-wise prevalence of dementia in the study was found to be consistent was supported by the fact that dementia or cognitive disorders increase with advancing age32. In our study, more females suffered from psychiatric illness in comparison to males as supported by other studies252730. More rural older adults belonging to lower socio-economic status had psychiatric illnesses than middle SES; this was similar to as reported by Tiwari8 and Poongothai et al30.

In conclusion, overall prevalence of psychiatric morbidity amongst rural elderly in this study was found to be less in comparison to those reported in previous studies from India. However, prevalence pattern of different disorders was almost similar. The study revealed that depression was the most common psychiatric morbidity, followed by mild cognitive impairment, substance abuse and dementia amongst the rural older adults.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India for providing financial assistance to carry out the study. Authors thank the project team, patients and their family members for their cooperation and help. Dedicated work of research staff Shrimati Rupali Sharma, Shri Ashutosh Mishra, Drs Monika Tandon, T.R. Pal, Shri Nityanand Pandey and Ms. Shweta Srivastava are acknowledged.

References

- Caregiver burden in an elderly population with depression in São Paulo, Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:416-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Population ageing and health in India. Mumbai, India: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes; 2006.

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: http://www.indexmundi.com/india/life_expectancy_at_birth.html

- 2011 Census of India. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2011_census_of_India

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of psychiatry morbidity in an urban community of Pondicherry. Indian J Psychiatry. 1993;35:99-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of prevalence and biosocial variables in mental illness in a rural and an urban community in Uttar Pradesh - India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1970;46:327-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders in subjects aged over fifty. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;22:193-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geriatric psychiatric morbidity in rural northern India: implications for the future. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:35-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric morbidity in non-psychiatric geriatric inpatients. Indian J Psychiatry. 2006;48:56-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- A community based study of psychiatric disorders among the elderly living in Delhi. 2008. The Internet Journal of Health. 7 Available from: http://archive.ispub.com/journal/the-internet-journal-of-health/volume -7-number-1/a-community-based-study-of-psychiatricdisorders-among-the-elderly-living-in-delhi.html#sthash

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuro-psychiatric morbidity amongst urban and rural elderlies in Northern India: Report from a community based epidemiological study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(Suppl 2):S136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric profiles in medical surgical populations: need for a focused approach to consultation-liaison psychiatry in developing countries. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:224-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression in the elderly in Vellore, South India: the use of a two-question screen. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:369-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of dementia in a rural setting: a report from India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:702-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of dementia is an urban population in Kerala, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:136-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency and distribution of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: A collaborative study of 1980-1990 prevalence findings. The EURODEM-Prevalence Research Group. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:381-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons. Higher than previously reported. JAMA. 1989;262:2551-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age-specific incidence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population. JAMA. 1995;273:1354-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Study of health and aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ. 1994;150:899-913. [No authors listed]

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiological surveys of senile dementia in Japan. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1991;37:51-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders in a rural community in West Bengal: an epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:87-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gerospsychiatric morbidity survey in a semi-urban area near Madurai. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:258-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of dementia in the community: a rural-urban comparison from Madras, India. Australas J Ageing. 1996;15:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric disorders in a rural community in West Bengal: An epidemiological study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:87-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalance of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in rural India. Indo-US study. Neurology. 1998;51:1000-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric morbidity of a rural Indian community. Changes over a 20 -year interval. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:351-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nature, prevalence and factors associated with depression among the elderly in a rural south Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:372-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of depression in a large urban South Indian population - The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURUS - 70) PLoS One. 2009;4:e7185.

- [Google Scholar]

- An epidemiological study of prevalence of neuro-psychiatric disorders with special reference to cognitive disorders amongst the urban elderly. Lucknow: Department of Geriatric Mental Health, CSM Medical University; 2009.

- [Google Scholar]

- Profile of neuropsychiatric morbidity amongst urban and rural elderly (preliminary observations) Indian J Ger Men Health. 2010;2:11-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dementia in Kerala, South India: prevalence and influence of age, education and gender. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:290-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A social psychiatric study of a representative group of families in Vellore town. Indian J Med Res. 1973;61:608-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development & standardization of a scale to measure socio-economic status in urban & rural communities in India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:309-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- A hindi version of the MMSE: The development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- The reliability of a Survey Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for the elderly. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;137:148-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Schedules for clinical assessment in neuropsychiatry version 2.1. Geneva: WHO; 1996.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders; diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva: WHO; 1993.

- [Google Scholar]

- CAMDEX. A standardised instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly with special reference to the early detection of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:698-709.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303-8.

- [Google Scholar]