Translate this page into:

Normative data of cervical length in singleton pregnancy in women attending a tertiary care hospital in eastern India

Reprint requests: Prof. Joydev Mukherji, IX/7, Citizens, 103, Maniktala Main Road, Kolkata 700 054, India e-mail: joydevmukherji@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives

The length of cervix predicts the risk of preterm delivery. The objective of this study was to assess cervical length in pregnancy by transvaginal ultrasonography for generating normative data for nulliparous women at no special risk of preterm labour.

Methods

An observational study was carried out in a tertiary care teaching hospital in eastern India in nulliparous women who delivered at term. A single sonologist assessed 224 women (once per subject) between 20 and 34 wk of gestation. Nulliparous women carrying a single foetus of confirmed gestational age were included; 216 subjects were finally considered for generation of normative data, excluding those delivering earlier than 37 or later than 42 wk. Other exclusion criteria were history of cerclage, any previous cervical surgery, smoking, or any medical disorder complicating pregnancy.

Results

Cervix length at each week of gestation gradually decreased over the study period. Length at 20 and 34 wk was 40.5 ± 1.14 mm (mean ± SD) and 34.8 ± 1.34 mm respectively. The overall shortening over this 14 wk period was 5.7 mm, with 0.58 mm per week median rate of shortening. Pearson's correlation coefficient was - 0.69 (95% CI - 0.75 to - 0.60; P< 0.001) for cervical length vis-à-vis gestational age.

Interpretation & conclusions

The serial normative data generated in our setting can be used to decide cut-off points for predicting risk of preterm labour in future studies. Validity of such prediction needs to be tested in larger cohorts of women assessed at specific gestational ages.

Keywords

Cervical length

normative data

preterm labour

transvaginal sonography

The risk of spontaneous preterm labour and delivery increases in women who have a short cervix1. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) can be used as an objective and reproducible method to measure cervical length throughout pregnancy. The gestational age at which cervical length is measured by TVS affects calculation of the risk of spontaneous preterm birth2. There is need for developing charts of cervical lengths, stratified by gestational age throughout pregnancy, in order to predict preterm labour. Several large studies have been carried out with measurements of the cervical length at fixed dates of 22 to 24 or 28 wk of gestation134. However, there are only a few reliable charts for low risk population, covering measurements at successive gestation weeks. Normative data for mean or median cervical lengths, along with corresponding measures of dispersion, stratified by gestational age, will not only help to monitor ongoing cervical changes but also to predict risk of preterm birth at any time of presentation. In future, when definitive interventions for prevention of preterm birth are expected to be available, it would be perhaps ethically unacceptable to withhold treatment if such normative data indicate substantial risk. Population based charts will also be useful to rule out false preterm labour, thereby obviating unnecessary hospitalizations and irrational use of corticosteroids and tocolytics.

As has been pointed out by Leitich et al5, mean cervical length, in addition to showing intersubject variability, appears to vary with ethnic identity. Consequently, it may be even more relevant to describe reference values of cervical lengths in various ethnic groups. However, at present there is lack of such data for the Indian population.

We therefore, conducted a study to establish normal cervical lengths using TVS, between 20 and 34 wk of gestation, for nulliparous women carrying a single foetus of confirmed gestational age. Only women who delivered between 37 to 42 wk were included in establishing the standard values.

Material & Methods

Consecutive nulliparous pregnant women were recruited between April, 2007 and May, 2008 in the antenatal outpatient department (once a week) of R. G. Kar Medical College Hospital, Kolkata, India, which is a tertiary care teaching hospital. The institutional ethics committee approved the study protocol and only those participants who provided written, informed consent were enrolled.

A cohort of nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies, and confirmed gestational age by first or early second trimester ultrasonography, were selected to undergo transvaginal sonographic measurement of cervical length between 20 and 34 wk gestation. Funneling was not taken as a criterion in this study as it is always associated with shortening of the cervix and does not provide any additional benefit in the prediction of preterm delivery67. Women beyond 34 wk were not included because antenatal corticosteroids are widely used up to 34 wk, therefore, there is no clinical implication even if patient goes into labour. The subjects were followed up for outcome of pregnancy and only the subset of women (determined retrospectively) who delivered between 37 to 42 wk was included for calculation of normal data for cervical length. Exclusion criteria were preterm labour or post-term pregnancy, induced labour, multiple pregnancy and history of cerclage or surgical intervention upon the cervix prior to pregnancy.

Although cervical length measurements were carried out for every week from 20 to 34 wk gestation, each woman underwent only a single cervical length measurement. Transvaginal sonography was done by a 7.5 MHz probe attached to an ultrasound machine (Agilent Electronics, Philips Medical System, Germany) in the radiology department of the institute. The probe was covered with a latex condom and gel placed between the transducer and the cover and also on the surface. It was then gently inserted in the vagina to obtain a sagittal view of the cervix. An adequate image for the measurement of cervical length was defined as the visualization of the internal os, external os and endocervical canal. The image was then frozen and cervical length measured, with electronic calipers, as the linear distance between the external os and the internal os along a closed endocervical canal. In instances where the cervical canal was curved, its length was assessed as the sum of the lengths of two contiguous linear segments, placed along the endocervical canal, connecting the external os and the internal os. The cervical length was measured thrice in each subject and the shortest of the three measurements was recorded1. The average time for examining one patient was 5 min. To maintain consistency and to reduce interobserver variation, all the measurements were carried out by a single ultrasonologist.

Data were captured on predesigned structured case report form. The analysis was done by Statistica version 6 (Tulsa, Oklahoma: Statsoft Inc., 2001) and GraphPad Prism version 4 (San Diego, California: GraphPad Software Inc., 2005) software. Descriptive values were presented for cervical length at every gestational week along with the results of parametric correlation and regression analysis. Confidence Interval (95% CI) values have been presented where deemed relevant.

Results & Discussion

A total of 224 nulliparous women were screened by TVS between 20 and 34 wk of gestation. The gestational age was confirmed by ultrasonography in the first trimester in 191 (85.3%) and by 16 wk in 33 (14.7%) women. Of these, 216 subjects (96.4%) were included for generation of normative data after excluding those with preterm and post-term delivery. The mean maternal age was 22.9 yr (range 17-33, standard deviation [SD] 3.05), while the mean gestational age at delivery was 38.1 wk (range 37-41, SD 1.04) in this study group.

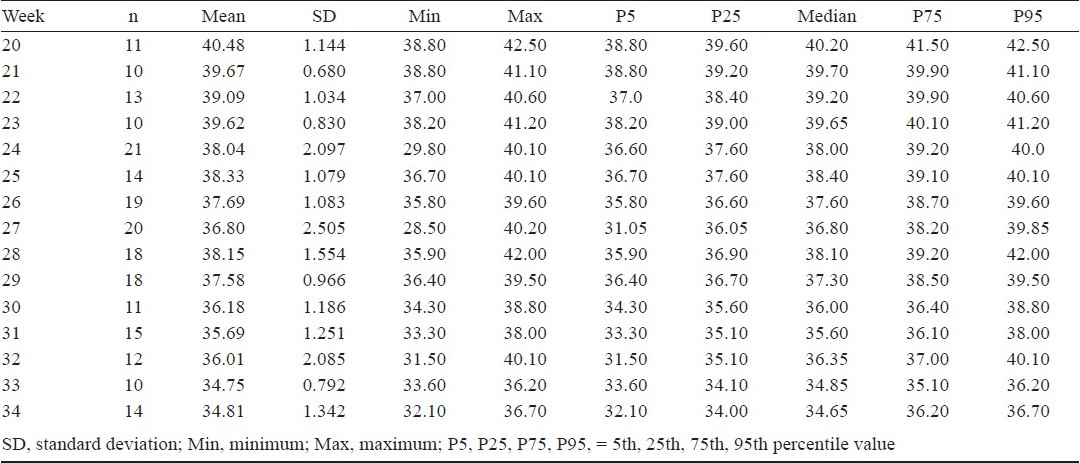

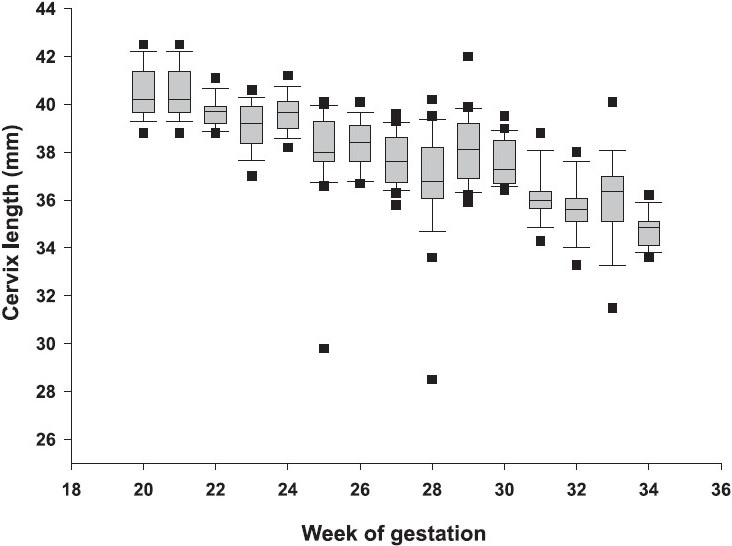

The number of subjects studied at each gestational week, along with the corresponding descriptive statistics for cervical length, as assessed by TVS, are presented in the Table and Fig. 1. The cervical length for each week of gestation gradually decreased over the study period. At 20 wk the 11 measurements gave a mean length of 40.5 mm, while measurements at 34 wk from 14 subjects gave a mean length of 34.8 mm. The overall shortening over this 14 wk period was 5.7 mm, with 0.58 mm per week median rate of shortening.

- Box and whisker plots of cervix length by transvaginal ultrasonography, stratified by gestational age, in nulliparous urban Indian women. Values falling outside a whisker length of 1.5 times the box range, have been depicted as outliers.

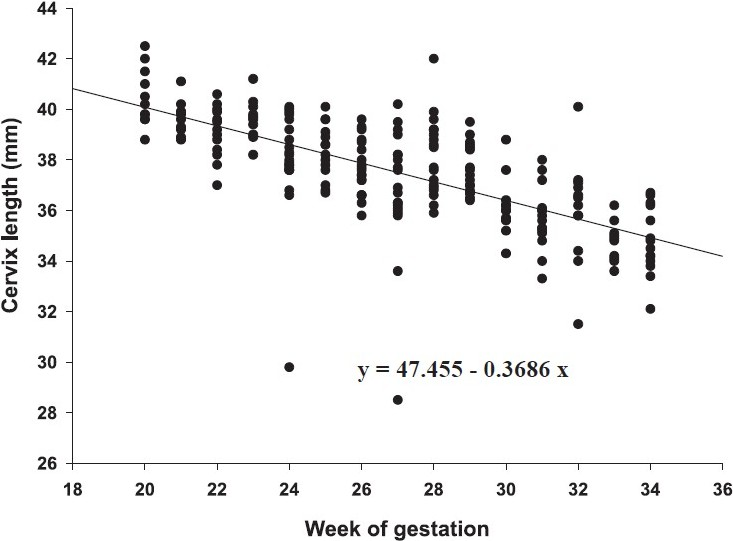

Association between cervical length and gestational age showed strong inverse correlation. Pearson's correlation coefficient ( r ) value was - 0.69 (95% CI - 0.75 to - 0.60); the statistical significance level for the correlation coefficient value (P<0.001) indicated that the same linear relationship holds in the underlying population. The coefficient of determination ( r2) value of 0.48 indicated a fairly good model fit. The simple linear regression line was y = 47.455 - 0.3686 x (where y is the cervical length in mm and x is the gestational age in weeks) (Fig. 2).

- Relationship between cervix length by transvaginal ultrasonography and gestational age in nulliparous urban Indian women.

This study was performed with measurements taken from a cohort of urban women with low risk of preterm labour attending an antenatal clinic, with the goal of generating normative data. Transvaginal measurement of cervical length has been reported for Indian women, but with different goals, such as prediction of outcome of induction of labour in women of 34 - 42 wk gestational age8, and prediction of the risk of preterm birth in asymptomatic women at high risk of such outcome9. We generated normative data from women at no special risk of preterm birth.

Our study showed that the cervical length gradually decreased, as gestational age advanced from 20 to 34 wk, and that there was significant inverse relationship between the two. Some researchers1011 have found that cervical length remains unchanged up to the third quarter and then becomes progressively shorter while others12–15 maintain that cervical length starts to decrease in the second quarter. Two longitudinal studies conducted between the 12th and 39th wk did not show any changes in cervical length throughout the period considered1617.

Iams et al1 found that the length of the cervix at 24 and 28 wk were 35.2 ± 8.3 and 33.7 ± 8.5 mm, respectively. Our study had corresponding values of 38.0 ± 2.1 and 38.1 ± 1.5 mm. The shorter cervical lengths in the earlier study could be due to the different racial profile, and the inclusion of subjects with higher baseline risk of preterm delivery and with funneling, both of which were exclusion criteria for the present study. The values of cervical lengths given by other researchers are however, similar to those from our study12141718.

The present study had two main limitations. Firstly, the measurements were started at 20 wk of gestation whereas many cases of cervical incompetence are detected by ultrasound beginning at 17 wk. However, indications of cervical length measurement prior to 20 wk are often a history of preterm delivery or previous surgical interventions on the cervix such as conisation or loop electro excision procedure (LEEP), whereas this study included only low risk women. Secondly, the sample size of this study was limited. Therefore, further studies should be done with larger number of subjects to generate normative data for Indian women.

There is also the need to determine the sensitivity and specificity of cut-off values, such as the 5th percentile value19 or a value 1 SD below the corresponding mean20, generated in this manner, in predicting risk of preterm labour at different gestational weeks. Recently a study21 has shown that increased cervical length at a median gestational age of 23 wk appears to independently predict cesarean delivery at term in primigravid women. This could be another area for research utilizing normative data of cervical length.

A randomized trial22 reported the results of vaginal progesterone supplementation to a group of women found to have a short cervix on routine ultrasonography at median 22 wk of gestation. Progesterone reduced the arte (about 15% absolute risk reduction) of early preterm delivery. These findings provide support for a strategy of routine screening of cervical length and prophylactic administration of progesterone to those with short cervix. However, it is also to be borne in mind that cervical incompetence is not the only contributory factor towards preterm labour and delivery, and no interventions can be recommended for women judged to have short cervix by the normative data generated in this study. However, the values generated through such studies can be used as baseline data for determining cut-off points for our population, which can then be utilized to select patients for prospective randomized controlled trials.

Authors thank the Principal, R. G. Kar Medical Colleges & Hospital, Kolkata, for allowing to carry out the study on women attending the hospital, using institutional resources.

References

- for National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:567-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gestational age at cervical length measurement and incidence of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:311-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length at 23 weeks of gestation: prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:312-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length and funneling at 23 weeks of gestation in the prediction of spontaneous early preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:200-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length and dilatation of the internal cervical os detected by vaginal ultrasonography as markers for preterm delivery: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1465-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second-trimester cervical ultrasound: associations with increased risk for recurrent early spontaneous delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:222-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transvaginal ultrasonography of the uterine cervix in hospitalized women with preterm labor. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72:117-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transvaginal measurement of cervical length in the prediction of successful induction of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:388-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervicovaginal HCG and cervical length for prediction of preterm delivery in asymptomatic women at high risk for preterm delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:565-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sonographic evaluation of cervical length in pregnancy: diagnosis and management of preterm cervical effacement in patients at risk for premature delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:939-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measurement of the pregnant cervix by transvaginal sonography: an interobserver study and new standards to improve the interobserver variability. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:188-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early prediction of preterm delivery by transvaginal ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1992;2:402-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of risk for preterm delivery by ultrasonographic measurement of cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:859-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length at 16-22 weeks’ gestation and risk for preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:972-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second-trimester cervical ultrasound: associations with increased risk for recurrent early spontaneous delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:222-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical changes throughout pregnancy as assessed by transvaginal sonography. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:960-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- A longitudinal study of the cervix in pregnancy using transvaginal ultrasound. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:16-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Charts for cervical length in singleton pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:161-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is sonographic assessment of cervical length better than digital examination in screening for preterm delivery in a low-risk population? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:1342-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transvaginal ultrasonographic cervical assessment for the prediction of preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Med. 1996;5:305-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening Group. Cervical length at mid-pregnancy and the risk of primary cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1346-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening Group. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:462-9.

- [Google Scholar]