Translate this page into:

Molecular approach for ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies in dogs

For correspondence: Dr Ajaz Ahmad, Department of Veterinary Pathology, College of Veterinary Science, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary & Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana 141 004, Punjab, India e-mail: ajazpatho786@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

The ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies is of great significance in establishing the status of infection in dogs, especially since they are involved in exposure to human beings. The present study was, therefore, undertaken to elucidate the most appropriate secretion/tissue for reliable diagnosis of rabies in 26 living dogs suspected to be rabid.

Methods:

In the present study 26 dogs suspected to have rabies were included for ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies in clinical samples of skin and saliva by molecular approach viz. heminested reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (HnRT-PCR). Skin and saliva samples were collected from 13 dogs each.

Results:

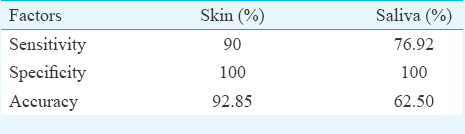

Of the 13 clinically suspected dogs, fluorescent antibody technique (FAT) confirmed rabies in nine cases of dogs. Of these nine true-positive dogs, eight cases could be confirmed by HnRT-PCR from skin. Of the other 13 dogs clinically suspected for rabies, FAT confirmed rabies in 10 cases. Of these 10 true-positive dogs, rabies was detected ante-mortem by HnRT-PCR from the saliva in seven dogs. Thus, rabies was detected from skin with 90 per cent sensitivity, 100 per cent specificity and 92.85 per cent accuracy. With saliva, rabies was detected with a sensitivity of 76.92 per cent, specificity of 100 per cent and accuracy of 62.50 per cent. The positive predictive values were 100 per cent for both skin and saliva samples while negative predictive values were 80 and 50 per cent, respectively.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Skin biopsy may be more appropriate clinical sample as compared to saliva for ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies in dogs. HnRT-PCR can be employed for molecular diagnosis of rabies from skin in live dogs.

Keywords

Ante-mortem

diagnosis

dogs

molecular technique

rabies

saliva

skin

Rabies is a fatal zoonotic disease of major concern and is still a public health hazard in many parts of the world, particularly Asia. Rabies is an endemic zoonotic disease in India. Worldwide, human mortality from enzootic canine rabies is estimated to be more than 55,000 deaths per year, of which approximately 56 per cent occur in Asia (20,000 in India alone) and 44 per cent in Africa, 99 per cent of which are transmitted by dogs1. Dog is the main vector responsible for the transmission of rabies to humans in 96.2 per cent cases (of which 62.9% are strays and 37.1% pets)2. The ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies by molecular approach therefore, assumes great significance. The present study was undertaken with the objective to compare the effectiveness of clinical samples (viz. skin and saliva) for ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies in dogs.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted in the rabies diagnostic laboratory at department of Veterinary Pathology, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary & Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, India, between January 2013 and December 2014. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee.

In the present study, skin biopsies (n=13) and saliva samples (n=13) were collected from dogs, clinically suspected for rabies and processed. Samples were collected from different districts of Punjab, wherein history of each case was collected and clinical signs of dog were recorded. Of the 26 dogs clinically suspected for rabies and included in the study, 16 had furious form while 10 dogs showed paralytic form. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of ante-mortem detection of rabies by molecular approach viz. heminested reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (HnRT-PCR) were evaluated.

Rabies was confirmed post-mortem by fluorescent antibody technique (FAT) on the brain tissue in all dogs included in the study. FAT was carried out according to Meslin et al3. Impression smear preparations of the brain samples were placed in a Coplin jar containing acetone and fixed at 4°C for one hour. The slides were air-dried and incubated with lyophilized, adsorbed anti-rabies nucleocapsid conjugate (Bio-Rad, France) against rabies for 35 min at 37°C in a humid chamber and further washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in three successive washes for 5-10 min. The previously inoculated albino mice brain tissue was used as positive control while fresh brain tissue of uninfected albino mice was used as negative control for FAT. The slides were rinsed with distilled water, air-dried and mounting buffered glycerol applied and then visualized under an immunofluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at ×400 magnification. Bright/dull/dim apple-green or yellow-green, round to oval intracellular accumulations were observed.

Sample collection: Before the start of the work, the prophylactic vaccination for rabies was carried out, and during sample collection, all the biosafety measures were taken viz. wearing full hand gloves, full sleeve aprons, masks, goggles, face shield and gum boots to prevent any exposure.

The skin biopsies were collected with the help of sterilized 3 mm skin biopsy punch from nape of the neck region4. Section of the skin with a diameter of 5-6 mm and weighing approximately 100 mg was taken ensuring that biopsy section comprised a minimum of 10 hair follicles. The skin biopsy was taken at a sufficient depth in the subcutaneous plane to include the cutaneous nerves at the base of the hair follicle. Ten milligrams of skin biopsy triturated in PBS of a normal cattle spiked with 100 μl of Rabipur anti-rabies vaccine was taken as positive control, and a duplicate sample of the skin without spiking of anti-rabies vaccine was taken as negative control.

The saliva was collected directly in sterilized containers or by swab method from the animals suspected to have rabies taking precautionary biosafety measures. PBS was added in saliva sample to make 1:1 suspension. In case of aggressive animal, soiled saliva samples were collected. The collected saliva was centrifuged and supernatant was used for the study. Three hundred microlitres saliva of normal cattle spiked with 100 μl of Rabipur vaccine was taken as positive control, and a duplicate sample without spiking by anti-rabies vaccine was taken as negative control.

Extraction of viral RNA: Total RNA was extracted directly from saliva and skin tissue using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 mg skin tissue was triturated and 400 μl saliva was homogenized with 1 ml Trizol and chloroform (Ambion Life Technologies, USA). RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, CA, USA) in ng/μl, and quality of RNA was checked as a ratio of OD 260/280 and stored at −80°C.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis & nucleic acid analysis: Total extracted RNA was converted into cDNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with RNAse Inhibitor (Applied Biosystems, USA)5. The resultant cDNA of the skin and saliva samples were used for HnRT-PCR.

Primary amplification: Primers used were based on N gene because it is the most conserved gene in the Lyssaviruses. Heminested set of primers used in the present study was that used earlier67. Amplification of 2 μl of the reverse-transcribed cDNA template was performed in a final volume of 25 μl; 12.5 μl 2X PCR mix (GoTaq Green Master Mix, Promega, USA), 1.0 μl of forward primer JW12 (10 pmol), 1.0 μl of reverse primer JW6 (10 pmol) and remaining part nuclease-free water. The amplification was performed on thermal cycler.

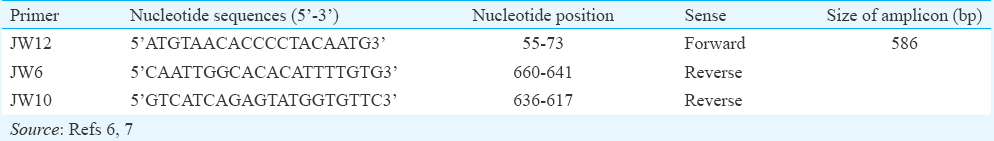

Hemi-nested amplification: Hemi-nested PCR was performed using 2 μl of the primary PCR product as template. Fresh master mix for second round of the PCR was prepared in PCR tubes, 1.0 μl of primer JW12 (10 pmol), 1.0 μl of primer JW10 (10 pmol). Secondary PCR was done as described above for the primary amplification. The primer set sequences are listed in Table I. On completion of the amplification programme, the samples were analyzed by 1 per cent agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining.

Results & Discussion

The gold standard diagnostic technique recommended by the World Health Organization1 is the demonstration of virus antigen in the brain tissue by the direct fluorescence assay (DFA). The DFA provides near 100 per cent sensitivity in post-mortem rabies diagnosis of humans and animals. However, the gold standard FAT is rendered insignificant when attempting diagnosis from non-nervous tissues as is the case in attempting ante-mortem diagnosis from secretions/tissues of clinically suspected animals. Ante-mortem diagnosis has become feasible by advent of molecular approaches such as RT-PCR8.

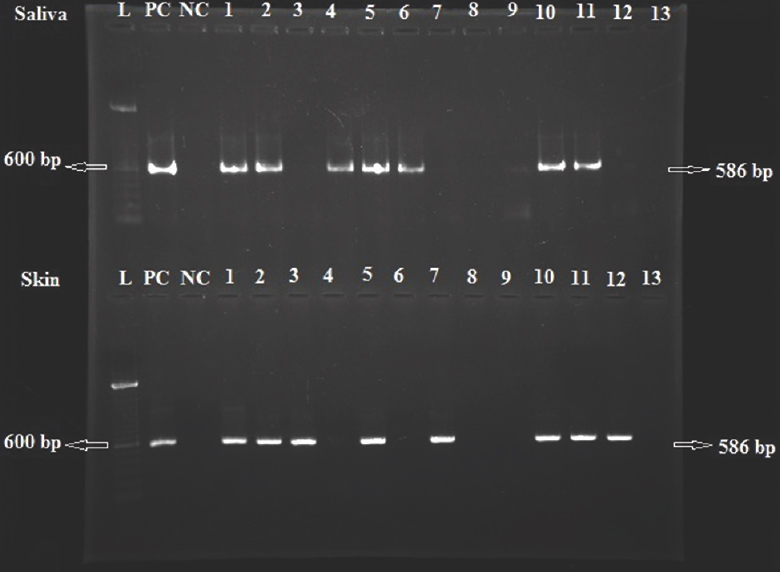

Of the 13 days clinically suspected to have rabies, FAT confirmed rabies in nine. Of these nine true-positive dogs, eight cases could be detected by HnRT-PCR from the skin. Of the other 13 dogs clinically suspected for rabies, FAT confirmed rabies in 10. Of these 10 true-positive dogs, rabies was detected ante-mortem by HnRT-PCR from the saliva in seven of the 10 dogs. RNA was extracted from the brain samples of all 26 dogs; 260/280 ratio of extracted RNA was in the range of 1.80-1.98. The primary PCR amplification yielded 606 bp products and second amplification of HnRT-PCR with forward primer (JW12) and reverse primer (JW10) yielded 586 bp product (Figure). Of the 13 clinically suspected dogs, eight were diagnosed positive for rabies from skin biopsies while seven dogs could be diagnosed from saliva using HnRT-PCR. Rabies was diagnosed from skin with sensitivity of 90 per cent, specificity of 100 per cent and accuracy of 92.85 per cent whereas rabies could be diagnosed from saliva with sensitivity of 76.92 per cent, specificity of 100 per cent and accuracy of 62.5 per cent (Table II). The positive predictive values were 100 per cent for both skin and saliva samples, while negative predictive values were 80 and 50 per cent for skin and saliva samples, respectively.

- Agarose gel (1%) stained with ethidium bromide. Lanes L, 100 bp ladder; NC, negative control; PC, positive control; 1-13, saliva samples (top lanes) and skin samples (bottom lanes).

Since there are no studies on skin diagnosis by HnRT-PCR targeting N gene, the results of HnRT-PCR were compared with studies on rabies diagnosis from skin samples using nested RT-PCR. Bansal et al9 diagnosed nine of 20 (45.0%) suspected cases whereas four of 11 (36.3%) cases were reported positive for rabies by Kaw et al10 using nested RT-PCR on skin samples. One study reported comparable sensitivity of 75.8 per cent by applying NSBA (nucleic acid-amplification) test on saliva samples4. Similarly, comparable sensitivity was also reported by Dacheux et al11 while Dandale12 reported 68 per cent sensitivity for detection of rabies from saliva samples. Wacharapluesadee et al13 in a study on samples from dogs confirmed to be infected with rabies virus using TaqMan real-time RT-PCR observed the sensitivity of 84.6 per cent, 81.8 per cent and 66.7 per cent when using oral swab samples, extracted whisker follicles and extracted hair follicles, respectively; the specificity of all specimen types was 100 per cent.

The present study had limitation of using separate dogs for the collection of skin and saliva samples. However, detection of rabies in both samples was compared with gold standard FAT for establishing the sensitivity of detection of rabies in skin and saliva samples from live dogs.

In conclusion, our findings showed skin to be more suitable clinical sample as compared to saliva for ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies in dogs. HnRT-PCR can be employed for molecular diagnosis of rabies from skin in live dogs suspected to have rabies.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge Dr S.N.S. Randhawa, Director of Research, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary & Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, for providing the necessary facilities.

Financial support & sponsorship: The present research work was carried out with the UGC grant under the scheme ‘UGC-11 Studies on Intra-vitam diagnosis of Rabies in Animals’.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2005;931:1-88.

- Epidemiological investigation of rabies in Punjab. Indian J Anim Sci. 2007;77:653-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory diagnosis of rabies. Geneva: WHO; 1996. p. :88-95.

- Ante- and post-mortem diagnosis of rabies using nucleic acid-amplification tests. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10:207-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of rapid immunodiagnosis assay kit with molecular and immunopathological approaches for diagnosis of rabies in cattle. Vet World. 2016;9:107-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on Anti-mortem Detection of Rabies from Skin: Patho Molecular Approaches. [M.V.Sc. Thesis]. Ludhiana, India: Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University; 2013.

- Heminested PCR assay for detection of six genotypes of rabies and rabies-related viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2762-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies by molecular approaches: Correlation study with clinical symptoms. Int J Agro Vet Med Sci. 2012;6:158-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ante-mortem diagnosis of rabies from skin: Comparison of nested RT-PCR with TaqMan real time PCR. Braz J Vet Pathol. 2012;5:116-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A reliable diagnosis of human rabies based on analysis of skin biopsy specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1410-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Molecular and Immunopathological Techniques for Ante Mortem Diagnosis of Rabies from Body Secretions and Excretions [MV Sc Thesis] Ludhiana, India: Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of rabies viral RNA by TaqMan real-time RT-PCR using non-neural specimens from dogs infected with rabies virus. J Virol Methods. 2012;184:109-12.

- [Google Scholar]