Translate this page into:

Mental health issues in antenatal women with prior adverse pregnancy outcomes: Unmasking the mental anguish of rainbow pregnancy

For correspondence: Dr Sujata Siwatch, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India e-mail: siwatch1@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Mental health issues in pregnancy have adverse implications on the quality of life, however still they go unevaluated and underreported. Women with previous history of abortions or stillbirth may have a higher risk of experiencing mental health problems. The present investigation was aimed to study the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress and domestic violence in antenatal women with prior pregnancy losses and the need for interventions to treat the same.

Methods:

One hundred pregnant women with a history of prior pregnancy losses (group 1) and 100 women without obstetrical losses (group 2) were enrolled in this cross-sectional study carried out in a tertiary care hospital in India. Women were screened for depression, anxiety, stress and domestic violence using various questionnaires: EPDS (Edinburgh postnatal depression scale), PRAQ-2 (pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire-revised 2), GAD 7 (generalized anxiety disorder-7) and PSS (perceived stress scale).

Results:

The prevalence of depression (EPDS scale) and pregnancy specific anxiety (PRAQ-2 scale) was significantly higher in group 1 than in group 2 (27 vs. 10%, P=0.008; and 15 vs. 6%, P=0.03). The prevalence of general anxiety (GAD 7 scale) and stress (PSS), however, was high and comparable in both the groups (33 vs. 29%, P=0.44; and 33 vs. 27%; P=0.35 respectively). Recurrent abortions was found to be an independent risk factor for depression [adjusted odds ratio=26.45; OR=28]. In group 1, 31 per cent required counselling in the psychiatry department and nine per cent required medication.

Interpretation & conclusion:

Mental health issues, especially depression, are prevalent in antenatal women with previous losses. Unrecognised and untreated, there is a need for counselling and developing screening protocols at India’s societal and institutional levels.

Keywords

Antenatal counselling

antenatal depression

miscarriage

pregnancy-specific anxiety

recurrent pregnancy loss

stillbirth

Depression, anxiety and stress are the most common psychiatric challenges faced during pregnancy and postpartum1. Physical and emotional symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression are misattributed as normal physical and hormonal changes in pregnancy. The prevalence of unipolar major depression in pregnant women is estimated to be seven per cent in the general population2 with records of it in developing countries like India being overall higher3. During pregnancy, mental health issues have various implications affecting their quality of life, such as nutritional deprivation and poor maternal weight gain4. Depression in pregnancy may persist into the postpartum period and lead to difficult parenting5. Studies show the association of antenatal mental health problems with foetal growth restriction (FGR) and low neonatal birth weight6,7. Women with a history of miscarriages are prone to marital disharmony and domestic violence8. In addition, poor social support, including conflict, ineffective communication and dissatisfaction with one’s partner, can further precipitate antenatal mental disorders. Studies show that abortions and perinatal loss increase the odds of depression and anxiety, and very few bereaved mothers with anxiety symptoms access psychiatric treatment9. India leads the world in having a high number of stillbirths. However, limited data are available evaluating mental health issues in antenatal women with recurrent abortions and stillbirths10. In this study, we aimed to determine the prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress, the occurrence of domestic violence and their correlation with perinatal outcome in subsequent pregnancy.

Material & Methods

This comparative cross-sectional study was conducted by the department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, a tertiary care hospital in northern India for a period of 18 months from July 2018 to December 2019. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (INT/IEC/2018/002160) and tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were strictly adhered to. Written informed consent for participation and publication was duly taken from all the study participants.

A total of 200 antenatal women were recruited from the Recurrent Abortions Clinic/Antenatal Clinic/Gynaecology and Maternity Ward of the hospital. The participants were divided into two groups. Group 1 consisted of antenatal women from the first, second or third trimester who had a previous history of stillbirths and/or recurrent pregnancy loss. Stillbirth was defined as a baby delivered with no signs of life and known to have died after 24 completed weeks of pregnancy or weighing 500 gm. Recurrent pregnancy loss was defined as the loss of three or more consecutive pregnancies until 24 wk of gestation. Group 2 included antenatal women with a viable pregnancy but without a history of stillbirth or recurrent pregnancy loss.

Assuming the prevalence of depression of 28 per cent in women with stillbirth and eight per cent in women without obstetrical losses11, after using the formula: n = (Z α/2 +Z β ) 2 × (p 1 (1-p 1 )+p 2 (1-p 2 )) / (p 1 -p 2 ), a sample size of 100 participants per group was considered at a 90 per cent power and 95 per cent confidence interval.

All participants were administered questionnaires in English/Hindi language, Edinburgh postnatal depression screening scale (EPDS) for depression, generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD 7) anxiety scale for pregnancy, pregnancy related anxiety questionnaire-revised 2 (PRAQ-2) for anxiety and perceived stress scale (PSS) for stress12-16. The intimate partner violence (IPV) questionnaire was used to screen for domestic violence. The questionnaires were self-administered in 85 per cent of the participants and assisted/read out by research workers in 15 per cent. Those who scored above the cut-off specific for the questionnaires were followed up in the psychiatry department for counselling/treatment with medications. While primary outcome was the prevalence of depression, secondary outcomes included the prevalence of anxiety, stress, domestic violence and the need for therapeutic intervention. The association of mental health issues with demographic factors, recurrent abortions, stillbirth, comorbidities, trimester of pregnancy and perinatal outcomes were studied under secondary outcomes.

Statistical analysis: Data were analysed using SPSS v 22.0 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY: USA). The comparisons of quantitative variables between the two groups were performed using the Student’s t test for age and Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test for categorical variables. The Spearman correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the relation between variables. Logistic regression analysis was carried out to find an independent factor associated with depression and anxiety.

Results and Discussion

The demographic characteristics of both the study groups were comparable (Table I).

| Sociodemographic and clinical parameters | Group 1 (n=100), n (%) | Group 2 (n=100), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr); mean±SD | 28.81±4.16 | 28.2±4.04 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate-9th class | 15 (15) | 22 (22) |

| 10th-12th class | 48 (48) | 31 (31) |

| Graduate | 24 (24) | 26 (26) |

| Post graduate | 13 (13) | 21 (21) |

| Occupation | ||

| Homemaker | 89 (89) | 84 (84) |

| Working | 11 (11) | 16 (16) |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 50 (50) | 55 (55) |

| Urban | 50 (50) | 45 (45) |

| Monthly income (₹), mean±SD | 25,086.73±65,796.66 | 18,346.96±14,132.73 |

| Up to 7000 | 10 (10) | 12 (12) |

| 7000-20,000 | 67 (67) | 63 (63) |

| 20,000-50,000 | 16 (16) | 19 (19) |

| >50,000 | 7 (7) | 6 (6) |

| Adverse life event | ||

| Yes | 6 (6) | 5 (5) |

| No | 94 (94) | 95 (95) |

| Married life (yr); mean±SD | 6.77±3.4 | 5.22±4.22 |

| Up to 5 | 47 (47) | 56 (56) |

| 6-10 | 39 (39) | 36 (36) |

| >10 | 14 (14) | 8 (8) |

| Type of marriage* | ||

| Arranged | 97 (97) | 91 (91) |

| Love | 3 (3) | 9 (9) |

| Type of conception | ||

| Spontaneous | 99 (99) | 97 (97) |

| Infertility treatment | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Period of gestation (wk)*, mean±SD | 24.08±8.2 | 28.43±7.71 |

| 0-14 | 19 (19) | 9 (9) |

| 15-28 | 48 (48) | 31 (31) |

| 29-32 | 19 (19) | 21 (21) |

| 33 and above | 14 (14) | 39 (39) |

| Number of abortions | ||

| 0-2 | 9 (9) | |

| 3-4 | 79 (79) | |

| 5-6 | 9 (9) | |

| 7 and above | 3 (3) | |

| History of stillbirth | 15 (15) | |

| History of stillbirth and recurrent abortions | 7 (7) | |

| Previous live births* | 30 (30) | 44 (44) |

| Medical complications | 25 (25) | 22 (22) |

| Pregnancy-related complications*** | 29 (29) | 52 (52) |

| Domestic violence | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Mental health problem | ||

| Depression (EPDS)** | 27 (27) | 10 (10) |

| Mild | 6 (6) | 0 |

| Moderate | 14 (14) | 6 (6) |

| Severe | 7 (7) | 4 (4) |

| Pregnancy-specific anxiety (PRAQ-2)* | 15 (15) | 6 (6) |

| GAD-7 Scale | 33 (33) | 29 (29) |

| Mild | 21 (21) | 23 (23) |

| Moderate | 8 (8) | 5 (5) |

| Severe | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Stress (PSS - moderate to high) | 33 (33) | 27 (27) |

| Drug therapy given | 9 (9) | 4 (4) |

| Counselling given | 31 (31) | 26 (26) |

| PRAQ-2**, mean±SD | 15.79±6.73 | 13.58±4.43 |

| Fear of giving birth, mean±SD | 5.91±3.20 | 5.39±2.76 |

| Fear of bearing a physically challenged child**, mean±SD | 4.48±2.55 | 3.5±1.16 |

| Concerns related to own appearance, mean±SD | 4.04±1.92 | 3.52±1.08 |

| PSS, mean±SD | 9.21±7.40 | 8.42±7.62 |

| GAD-7, mean±SD | 3.8±4.54 | 2.91±3.96 |

| EPDS***, mean±SD | 5.22±5.32 | 2.99±4.39 |

P*≤0.05, **≤0.01 ***≤0.001. EPDS, Edinburgh postnatal depression screening scale; PRAQ-2, pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire- revised 2; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; PSS, perceived stress scale; SD, standard deviation

Anxiety: A meta-analysis of 19 studies published in 2017 showed that women with a previous history of perinatal loss had higher anxiety levels17. In our study, the prevalence of pregnancy-specific anxiety was high in group 1; however, general anxiety was high in both the groups (Table I). Women with previous losses had 3.1 times higher odds of suffering from anxiety after adjusting for the difference in the period of gestation, pregnancy related complications, income and previous live births, though the same were not significant. Anxiety rate did not differ with the number of abortions (Table II). The maximum prevalence of anxiety was found in the first trimester in group 2 (Table III). In group 1, the highest anxiety was found in the 15-28 wk period of gestation, and general anxiety persisted even after crossing the period of gestation of previous pregnancy loss.

| Mental health problem | 0-2 abortions (n=9), n (%) | 3-4 abortions (n=79), n (%) | 5-6 abortions (n=9), n (%) | 7 and above (n=3), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress** | ||||

| Low stress | 5 (55.6) | 59 (74.7) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (33.3) |

| Moderate high stress | 4 (44.4) | 20 (25.3) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (66.7) |

| Depression*** | ||||

| No depression | 7 (77.8) | 63 (79.7) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (66.7) |

| Mild depression | 0 | 5 (6.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 |

| Moderate depression | 2 (22.2) | 7 (8.4) | 5 (55.6) | 0 |

| Severe depression | 0 | 4 (5.1) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (33.1) |

| Anxiety | ||||

| No anxiety | 5 (55.6) | 57 (72.2) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) |

| Mild/moderate/high anxiety | 4 (44.4) | 22 (27.8) | 6 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) |

P **≤0.01, ***≤0.001. P values were calculated with continuity correction

| 0-14 wk, n (%) | 15-28 wk, n (%) | 28-32 wk, n (%) | 33 wk and beyond, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health problem | ||||

| Group 1, n | 19 | 48 | 19 | 14 |

| Group 2, n | 9 | 31 | 21 | 39 |

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | ||||

| Group 1 | 5 (26.3) | 19 (39.6)** | 6 (31.6) | 3 (21.4) |

| Group 2 | 4 (44.4) | 4 (12.9) | 8 (38.1) | 13 (33.3) |

| Depression | ||||

| Group 1 | 4 (21.1) | 14 (29.2)* | 5 (26.3) | 4 (28.6)* |

| Group 2 | 3 (33.3) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (5.1) |

| Moderate-high stress | ||||

| Group 1 | 7 (36.8) | 18 (37.5) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (14.3) |

| Group 2 | 4 (44.4) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (23.8) | 11 (27.2) |

P *<0.05, **≤0.01. There was no significant difference in prevalence of mental health problems in both the groups in different periods of gestation; group 1 had significantly high prevalence of anxiety and depression than group 2 between 15-28 wk and also had significantly higher prevalence of depression beyond 33 wk

Depression: Prevalences of depression in women in group 1 and group 2 were 27 and 10 per cent, respectively, and the difference was significant (P=0.008; OR=3.32) with a significantly higher mean score in group 1 (Table I). This is comparable with other studies18-21. Group 1 had 3.1 times higher odds of suffering from depression after adjusting for the difference in the period of gestation, pregnancy-related complications, income and previous live births (P=0.01). This difference was seen significantly in women with previous losses between 15-28 wk and beyond 33 wk (Table III). Recurrent abortion was found to be an independent risk factor associated with depression after adjusting for the effects of confounding factors such as age, income, married life years, period of gestation, history of live birth and pregnancy complications (adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=26.45; 95% C.I: 1.84-378.92; P=0.01; OR=28). Sofia Rallis, in their study, concluded that maximum depression was found at 16 and 32 wk of gestation1. However, in our study, it was more prevalent between 15 and 28 wk in group 1 and initial 14 wk in group 2 (Table III).

Stress: Prevalences of stress (assessed by the PSS) in group 1 and group 2 were 33 and 27 per cent (P=0.358), respectively (Table I). The stress levels were similar in the two groups after adjusting for the gestation of previous loss, pregnancy-related complications, previous live births and income status. In group 1, a positive correlation was found between stress as the number of abortions increased (P=0.004; Table II). High stress levels in the control group could be due to physical changes, emotional changes, increased demands in the form of need for frequent antenatal check-ups, increased dietary requirements, increased expenditure and social pressure. However, it could also be due to the participants being chosen from a tertiary care referral institute.

Domestic violence: The prevalence of domestic violence was three per cent in group 1 compared to one per cent in group 2; the difference was not significant.

Drug abuse: A study conducted by Carvalho et al21 in Brazil reported a 13 per cent prevalence of drug abuse, but it was not prevalent in our study population.

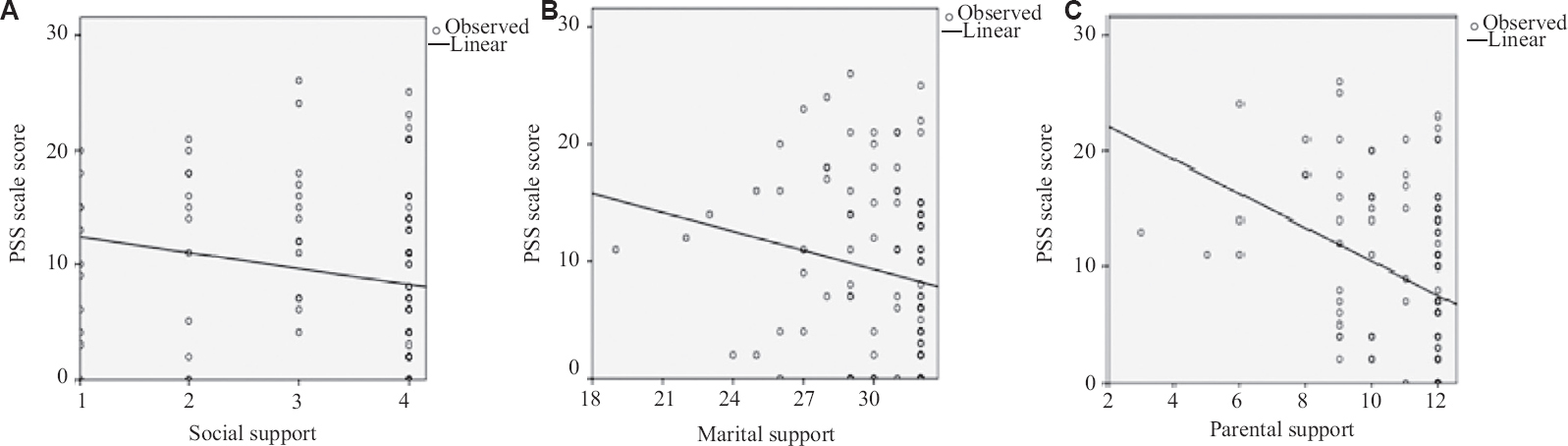

Effect of social, marital and parental support: The presence of marital, parental and social support was inversely correlated with perceived stress (correlation coefficient (r)-0.28, P=0.005, OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79-1.10; r -0.41, P<0.001, OR 0.81 95% CI 0.64-1.04 and r -0.22, P=0.03, OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.49-1.11 respectively; Figure).

- Scatter plots of correlation of stress with (A) social, (B) marital, and (C) parental support. PSS, perceived stress scale

Obstetric outcomes: In our study, anxiety and depression were more prevalent in group 1, but these did not lead to an adverse obstetric outcome. This is in contrast to previous studies, which had shown an association of FGR with antenatal depression4.

Intervention: It is noteworthy that 57 (28%) participants required counselling (31 from group 1 and 26 from group 2) and 13 (5.5%) required drug therapy (9 from group 1 and 4 from group 2). Although the differences in group 1 and group 2 for counselling and drug therapy were not significant, our study revealed the differences existing in these groups. Starting on psychiatric medications in antenatal patients is itself accompanied by fear of potential side effects on the foetus, ultimately affecting compliance. Family and the social environment might influence their decision-making in this regard.

This study was not without limitations. There may have been a selection bias as it was a single facility based study that did not represent the general population. The study was also limited by self-report bias. However, this study adds to the already existing knowledge, and can help us to plan antenatal services in rainbow pregnancy clinics. To conclude, our study highlights that pregnancy specific anxiety and depression are significantly more prevalent in women with bad obstetric history, which is evident from significant differences in PRAQ-2 and EPDS scores. Recurrent abortion was an independent risk factor associated with depression. There is a need to develop social support, community-level screening, institutional protocols and addressing mental health issues in health programmes, which have largely remained uncatered. Developing such protocols in a low- and middle-resource setting like India and building coping mechanisms to overcome mental health issues during pregnancy is the need of the hour.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgment:

Authors acknowledge Ms Kusum Chopra for the statistical analysis.

References

- A prospective examination of depression, anxiety and stress throughout pregnancy. Women Birth. 2014;27:e36-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and treatment among U. S. pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005-2009. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21:830-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:139G-49G.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of antenatal depression on maternal dietary intake and neonatal outcome: A prospective cohort. Nutr J. 2016;15:64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: A literature review. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:34-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of maternal psychological distress on fetal weight, prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation. J Affect Disord. 2008;111:214-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women Birth. 2015;28:179-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Marriage and cohabitation outcomes after pregnancy loss. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1202-1202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder 9 months after perinatal loss. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:650-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- World making barely any progress on preventing stillbirths, says Lancet. Available from: http:// www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/jan/18/world- progress-preventing-stillbirths-lancet-africa

- Stillbirth as risk factor for depression and anxiety in the subsequent pregnancy: Cohort study. BMJ. 1999;318:1721-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale against both DSM-5 and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for depression and anxiety disorders from pregnancy to postpartum with the EPDS and STAI. Span J Psychol. 2014;17:E7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adaption of pregnancy anxiety questionnaire-revised for all pregnant women regardless of parity: PRAQ-R2. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19:125-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety scale for pregnancy:development and validation (T). Available from: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.00∡9

- The presence of anxiety, depression and stress in women and their partners during pregnancies following perinatal loss: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;223:153-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective cohort study of depression in pregnancy, prevalence and risk factors in a multi-ethnic population. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of perinatal depression: A cohort study from urban Pakistan. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:395-403.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety, depression and relationship satisfaction in the pregnancy following stillbirth and after the birth of a live-born baby: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression in women with recurrent miscarriages –An exploratory study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2016;38:609-14.

- [Google Scholar]