Translate this page into:

Laparoscopic evaluation of female genital tuberculosis in infertility: An observational study

For correspondence: Dr Jai Bhagwan Sharma, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: jbsharma2000@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Female genital tuberculosis (FGTB) is an important variety of extrapulmonary TB causing significant morbidity, especially infertility, in developing countries like India. The aim of this study was to evaluate the laparoscopic findings of the FGTB.

Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study on 374 cases of diagnostic laparoscopy performed on FGTB cases with infertility. All patients underwent history taking and clinical examination and endometrial sampling/biopsy for acid-fast bacilli, microscopy, culture, PCR, GeneXpert (only last 167 cases) and histopathological evidence of epithelioid granuloma. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in all the cases to evaluate the findings of FGTB.

Results:

Mean age, parity, body mass index and duration of infertility were 27.5 yr, 0.29, 22.6 kg/m2 and 3.78 years, respectively. Primary infertility was found in 81 per cent and secondary infertility in 18.18 per cent of cases. Endometrial biopsy was positive for AFB microscopy in 4.8 per cent, culture in 6.4 per cent and epithelioid granuloma in 15.5 per cent. Positive peritoneal biopsy granuloma was seen in 5.88 per cent, PCR in 314 (83.95%) and GeneXpert in 31 (18.56%, out of last 167 cases) cases. Definite findings of FGTB were seen in 164 (43.86%) cases with beaded tubes (12.29%), tubercles (32.88%) and caseous nodules (14.96%). Probable findings of FGTB were seen in 210 (56.14%) cases with pelvic adhesions (23.52%), perihepatic adhesions (47.86%), shaggy areas (11.7%), pelvic adhesions (11.71%), encysted ascites (10.42%) and frozen pelvis in 3.7 per cent of cases.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The finding of this study suggests that laparoscopy is a useful modality to diagnose FGTB with a higher pickup rate of cases. Hence it should be included as a part of composite reference standard.

Keywords

Adhesions

beaded tubes

caseous nodules

complications

diagnostic laparoscopy

endometrial sampling

tubercles

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to be a global problem but more so in developing nations, with drug-resistant TB compounding the problem1,2. Although pulmonary TB remains the most common type of TB globally, the incidence of extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) is on the rise, especially due to co-infection with HIV, and this accounts for about 20 per cent of cases3. Female genital tuberculosis (FGTB) is observed in about 5-30 per cent of infertility cases3. The prevalence of FGTB varies in different countries and in different parts of India being 45.1 per cent of the patients per 1,00,000 population in the Andaman Islands to about 1-19 per cent in infertile patients being higher (about 16%) in tertiary referral centres and are still higher (up to 41%) in patients coming for in vitro fertilization with tubal factor infertility (up to 48.5%)4-7.

FGTB may be asymptomatic or manifest with menstrual abnormalities especially oligomenorrhoea, hypomenorrhoea, abdominopelvic pain and pelvic mass5-8.

Conventionally, diagnosis of genital TB is made by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) on microscopic examination or BACTEC culture or mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT) culture or presence of epithelioid granuloma on endometrial or peritoneal biopsy. These are infrequently present and may lead to missing the diagnosis in majority of patients5,7.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive test but has high rate of false positivity and hence, should not be used to start treatment5,8,9. Gene Xpert is specific and has been endorsed by the World Health Organization but has low sensitivity to detect FGTB10,11. Unlike pulmonary TB, diagnosis of EPTB, including FGTB, is difficult due to its paucibacillary nature. Dosanjh et al12 tried to combine various methods of diagnosis of detection of tuberculosis which is a type of composite reference standard (CRS). Later, other authors formed CRS for FGTB also along with the other types of FGTB13.

Composite Reference Standard (CRS) has become popular in the detection of genital TB and takes into consideration demonstration of Mycobacterium on microscopic examination or culture of endometrial/peritoneal biopsy or epithelioid granuloma on histopathology or positive Gene Xpert and definite findings (beaded tubes/caseous nodules/tubercles) or probable findings (ascites, white areas, pelvic/abdominal/perihepatic adhesions, distended tubes, pyosalpinx and tubo-ovarian masses) on laparoscopy13.

Laparoscopy by direct visualization of the abdomen and pelvis can detect most cases of FGTB missed by traditional tests and can be a part of CRS thus, can show a definite or probable finding of FGTB and also help in prognostication of infertility in addition to plan further treatment5,9,12-14. Although previous smaller studies of short duration have observed laparoscopy to be useful in the detection of FGTB, a bigger study with large sample size is needed for confirmation of findings of the prior studies.

Hence, the present study was done to report the laparoscopic observations in FGTB over a nine-year period, to help the clinicians in their day-to-day practice.

Material & Methods

This study was carried out at the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, after seeking approval by the Institute Ethical Committee. An informed written consent was also taken from all the participants prior to the start of the study.

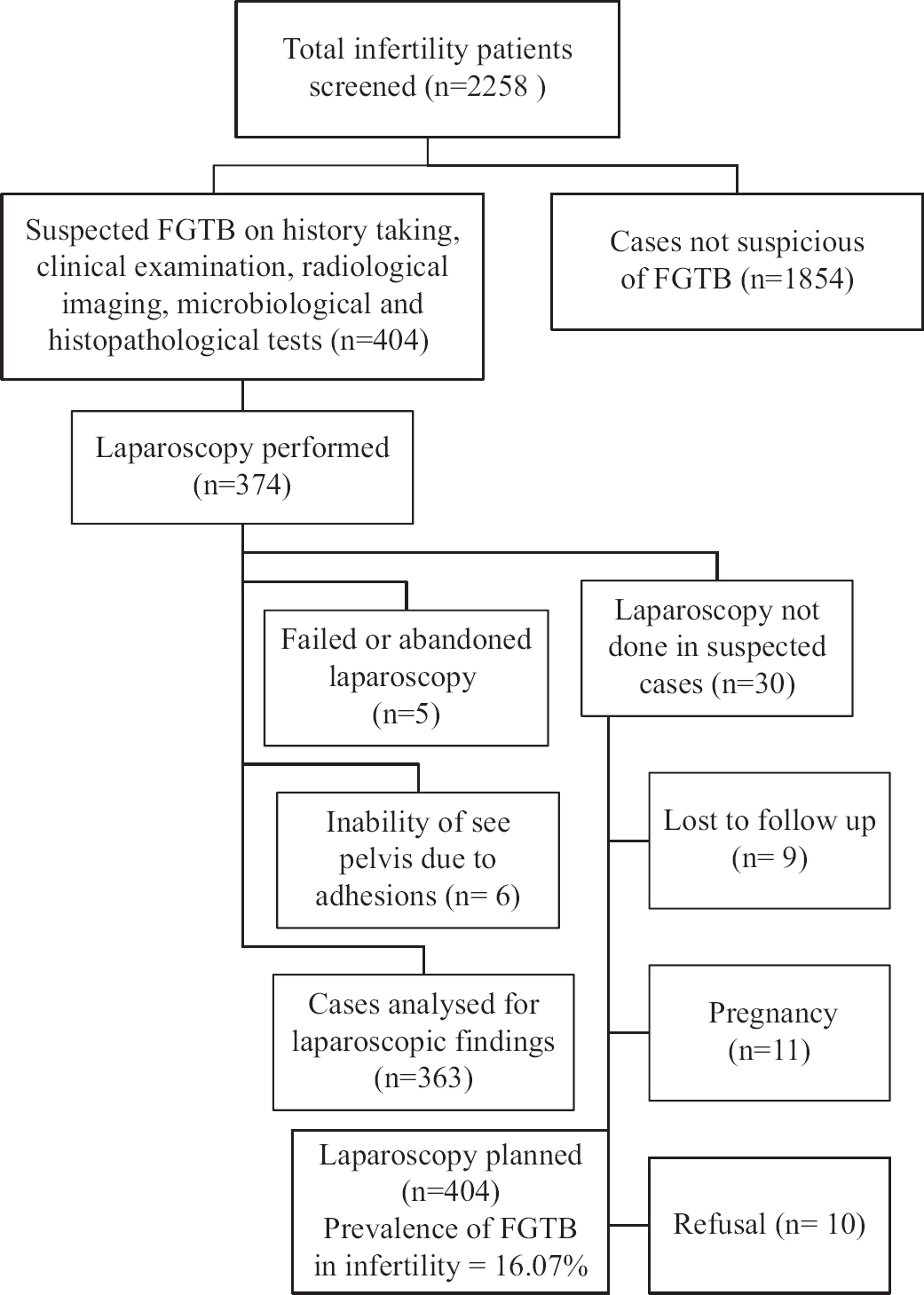

Study design: This was a cross-sectional study on 374 consecutive cases of diagnostic laparoscopy (pelviscopy) performed on FGTB with infertility as shown in Figure for nine years (July 2010 to July 2019) in an apex tertiary referral institute between 20 and 40 years. Inclusion criteria included infertile patients who were willing to participate in the study and had FGTB on CRS as in Figure which was formed for FGTB taking into consideration the study of Dosanjh et al12 in 2008. Exclusion criteria included women with malignancy or any other gynaecological disease and who were not willing to participate.

Complete medical/obstetric history and history of TB was taken from all participants. General physical and gynaecological examinations including bimanual examination for uterine size and adnexal mass and tenderness were performed on all the participants.

Laboratory investigations and microbiological tests: Baseline investigations such as complete haemogram, Mantoux test, blood sugar, X-ray chest and ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan where abdominal or pelvic lump was palpable were performed on all participants. Endometrial biopsy/aspirate was taken from all the participants between day 21 and 24 of the menstrual cycle with no. 4 Karman’s cannula in gynaecological outpatient minor operation theatre under all aseptic conditions; one part of the sample was sent in saline for detection of M. tuberculosis on microscopy and for culture, PCR and GeneXpert test. The second part of the sample was kept in formaldehyde solution for detection of tuberculous granuloma on histopathology.

Laparoscopy: Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in all the cases under short general anaesthesia using no. 10 mm laparoscope (Karl Storz, Germany) as part of the infertility workup, and for findings of TB and for prognostication and treatment planning for infertility. During laparoscopy, the whole of the pelvis and abdomen along with their contents was meticulously examined for any definite or probable findings of FGTB. The laparoscopic findings were analyzed in two time periods (July 2010 to December 2014 and January 2015 to July 2019) to see changing patterns in laparoscopic findings and complications over time.

All patients with FGTB diagnosed by microscopy, culture, Gene Xpert, histopathology or laparoscopy were treated with anti-tubercular therapy as per the protocol of the hospital where laparoscopic evidence of FGTB is taken as evidence of FGTB and treatment is started even in the absence of microbiological and histopathological evidence. Participants were given full oral anti-tubercular therapy for six months (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol daily for two months in intensive phase, followed by rifampicin, isoniazid and ethambutol daily for the next four months in continuation phase) through Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) strategy. The patients were kept on a regular follow up for compliance and any side effects of drugs. In the present study, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed for all suspected and confirmed cases of FGTB as part of research project and infertility protocol for tubal patency, confirmation of diagnosis and prognostication of the disease.

Criteria for the diagnosis of FGTB as per Composite Reference Standard (CRS): As per the study by Dosanjh et al12 in 2008, FGTB was diagnosed in the presence of positive AFB on microscopy or culture or positive Gene Xpert or positive epithelioid granuloma on histopathology of endometrial or peritoneal biopsy or definite or probable findings of FGTB on laparoscopy. PCR being non-specific was not taken as part of CRS. By combining various tests in CRS, most cases which otherwise would have been missed by traditional methods could be diagnosed and treated on time.

Statistical analysis: Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for continuous data using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation and range) were carried out for normally distributed data. Comparison of means across two groups was done using Student’s t independent test and comparison of categorical values was done by Chi-square/Fisher’s exact test.

Results

A total of 2258 patients screened for FGTB over a period of nine years, a total of 404 were suspected to have FGTB on histopathology taking, clinical examination, radiological imaging, microbiological and histopathological findings with the prevalence of FGTB. Out of the 404 cases, laparoscopy could not be done in 30 patients (9 patients were lost to follow up, 11 got pregnant while waiting for laparoscopy, and 10 refused laparoscopy; Figure).

- Diagnostic algorithm. FGTB, female genital tuberculosis

Out of 374 women in whom laparoscopy was tried, findings were seen in 363 cases, as laparoscopy was abandoned in five patients and pelvis could not be seen due to adhesions in six patients. Hence, only 363 cases with proven FGTB on laparoscopy were taken, making the prevalence of FGTB in infertility to be 16 per cent. Another 110 patients not found to have FGTB also underwent laparoscopy for other reasons and were not included in the study.

The general characteristics of the participating women are shown in Table I, with mean age being 27.5±4.8 yr while mean parity was 0.29±0.12 and mean body mass index was 22.6±2.58 kg/m2. History of tuberculosis was seen in 145 (38.77%), with pulmonary TB in 24.59 per cent and EPTB in 14.17 per cent of cases. Infertility was seen in all women, with a mean duration of infertility being 3.78±1.58 yr. Primary infertility was seen in 81.81 per cent of cases and secondary infertility in 18.18 per cent of cases. A total of 246 (65.77%) patients were from a lower socioeconomic status. History of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine was observed in 84.49 per cent of cases.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | |

| Range | 18-45 |

| Mean±SD | 27.5±4.8 |

| Parity | |

| Range | 0-4 |

| Mean±SD | 0.29±0.12 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |

| Range | 15.8-35.5 |

| Mean±SD | 22.06±2.58 |

| Part history of tuberculosis | 145 (38.77) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 92 (24.59) |

| Extrapulmonary tuberculosis | 53 (14.17) |

| Duration of infertility (yr) | |

| Range | 1-14 |

| Mean±SD | 3.78±1.58 |

| Type of infertility | |

| Primary infertility | 306 (81.81) |

| Secondary infertility | 68 (18.18) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Lower | 246 (65.77) |

| Middle | 119 (31.81) |

| Upper | 9 (2.40) |

| History of BCG vaccination | 316 (84.49) |

SD, standard deviation; BCG, bacillus Calmette–Guérin

The clinical features, examination findings and baseline investigations are depicted in Table II. Menstrual symptoms were most common, especially hypomenorrhoea in 27.80 per cent and oligomenorrhoea in 29.67 per cent of cases. Adnexal mass was palpable in 68 (18.18%) being unilateral in 46 (12.29%) and bilateral in 22 (5.8%) cases. Infectious Mantoux test (>10 mm) was observed in 142 (37.96%) cases, while erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ranged between 12 and 69, with a mean of 32.74±12.84 mm in the first hour. On X-ray chest, old healed lesions of tuberculosis were seen in 26 (6.95%) and enlarged thoracic lymph nodes were seen in 18 (4.81%) cases.

| Symptoms/signs | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fever | 67 (17.91) |

| Anorexia | 127 (33.95) |

| Weight loss | 119 (31.81) |

| Malaise | 115 (30.74) |

| Night sweats | 82 (21.92) |

| Menstrual symptoms | |

| Normal menstrual cycle | 194 (51.87) |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 8 (2.13) |

| Hypomenorrhoea | 104 (27.80) |

| Oligomenorrhoea | 111 (29.67) |

| Secondary amenorrhea | 28 (7.48) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 29 (7.75) |

| Abdominal pain | 38 (10.16) |

| Chronic pelvic pain | 48 (12.83) |

| Vaginal discharge | 38 (10.16) |

| Signs | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 12 (3.20) |

| Abdominal mass | 34 (9.09) |

| Speculum examination | |

| Normal speculum examination | 226 (60.42) |

| Abnormal vaginal discharge on examination | 142 (37.96) |

| Cervical growth (later confirmed cervical tuberculosis) | 4 (1.06) |

| Adnexal mass | 68 (18.18) |

| Unilateral | 46 (12.29) |

| Bilateral | 22 (5.88) |

| Baseline investigations | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | |

| Range | 8.4-14.2 |

| Mean±SD | 11.8±0.98 |

| Anaemia (Hb <11 g/dl) | 67 (17.11) |

| Total leucocyte count (per cubic mm) | |

| Range | 3887-12187 |

| Mean±SD | 5585±2274 |

| Random blood sugar (mg/dl) | |

| Range | 76-206 |

| Mean±SD | 112.68±16.88 |

| Abnormal infectious Mantoux test (>10 mm) | 142 (37.96) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/first hour) | |

| Range | 12.69 |

| Mean±SD | 32.74±12.84 |

| X-ray chest | |

| Normal X ray chest | 330 (88.23) |

| Old healed lesion of TB | 26 (6.95) |

| Mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 18 (4.81) |

*Some patients had more than one finding, CBNAAT could only be done for the last 167 cases. AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CBNAAT, cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test

The numbers of patients based on methods of diagnosis of FGTB are shown in Table III. Positive MTB on microscopy of endometrial aspirate or biopsy was observed in 18 (4.81%) cases, 24 (6.41%) on culture, tuberculous granuloma on histopathology in 58 (15.50%) cases while on peritoneal biopsy, AFB microscopy or culture were seen in 14 (3.94%) cases, epithelioid granuloma was seen in 22 (5.88%) cases. Positive PCR on endometrial or peritoneal biopsy was seen in 314 (83.95%) cases. GeneXpert was positive in 31 (18.56%) cases out of 167 cases. If non-specific PCR was excluded, only 90 patients had definite evidence of FGTB on microscopy, culture, Gene Xpert or positive histopathology, with many patients having more than one positive finding. Hence, out of 363 cases, 273 were missed by traditional tests but diagnosed by laparoscopy. Definite findings of tuberculosis (tubercles, caseous nodules and beaded tubes) were seen in 164 (43.85%) cases, while probable findings of FGTB (straw-coloured fluid, pelvic adhesions, perihepatic adhesions, hyperaemic tubes, convoluted tubes, hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx and shaggy areas) were seen in 210 (56.14%) cases.

| Diagnostic modality | Number of women, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Positive AFB on microscopy of endometrial aspirate or biopsy | 18 (4.81) |

| Positive AFB on culture of endometrial aspirate or biopsy | 24 (6.41) |

| Positive AFB on microscopy or culture on peritoneal biopsy | 14 (3.94) |

| Epithelioid granuloma or chronic granulomatous endometrium on histopathology of endometrial biopsy | 58 (15.50) |

| Epithelioid granuloma on histopathology of biopsy from peritoneal lesions or caseous nodule | 22 (5.88) |

| Positive CBNAAT or GeneXpert on endometrial or peritoneal biopsy | 31 (out of 167 cases) (18.56) |

| Positive PCR on endometrial aspirate or peritoneal biopsy | 314 (83.95) |

| Definite findings of female genital tuberculosis on laparoscopy | 164 (43.85) |

| Probable findings of female genital tuberculosis on laparoscopy | 210 (56.14) |

*Some patients had more than one finding, CBNAAT could only be done for the last 167 cases. AFB, acid-fast bacilli; CBNAAT, cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test

Various abdominopelvic findings of TB on laparoscopy are shown in Table IV. The laparoscopy was abandoned or failed due to umbilical adhesions in five (1.377%) women and there was inability to see the pelvis due to adhesions in another six women. Of the definite findings, tubercles were seen mostly on uterus in 123 (33.68%) women (

| Laparoscopic | n (%) | July 2010-December 2014 (n=178), n (%) | January 2015-July 2019 (n=185), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite findings | |||

| Beaded tubes | |||

| Overall | 46 (12.29) | 21 (11.79) | 25 (13.54) |

| Bilateral | 34 (36) | 5 (2.81) | 19 (10.25) |

| Unilateral | 12 (30) | 10 (5.62) | 6 (3.241) |

| Tubercles | |||

| On uterus | 123 (33.88) | 59 (33.15) | 64 (36.59) |

| On fallopian tube | 111 (30.57) | 56 (31.46) | 55 (29.73) |

| On ovaries | 39 (14) | 14 (7.87) | 15 (8.11) |

| On pouch of Douglas | 58 (97) | 30 (16.85) | 28 (15.14) |

| On pelvic peritoneum | 74 (20.38) | 35 (19.66) | 39 (21.08) |

| On general peritoneal cavity | 22 (6.06) | 10 (5.62) | 12 (6.49) |

| Caseous nodules overall | 56 (15.42) | 29 (16.29) | 27 (14.59) |

| Pelvic region | 44 (12.12) | 23 (12.92) | 21 (11.35) |

| General peritoneum | 12 (3.30) | 6 (3.37) | 6 (3.24) |

| Probable findings | |||

| Adhesions | |||

| Pelvic adhesions | 198 (54.54) | 106 (59.55) | 92 (49.73) |

| Perihepatic adhesions (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) | 179 (49.31) | 94 (52.81) | 85 (45.95) |

| Abdominal adhesions | 88 (24.24) | 52 (29.21) | 36 (19.46) |

| Shaggy areas (white deposits) | |||

| Overall | 44 (12.12) | 21 (11.80) | 23 (12.43) |

| On uterus | 22 (6.06) | 10 (5.62) | 12 (6.49) |

| Fallopian tube | 14 (3.74) | 7 (3.93) | 7 (3.78) |

| Pouch of Douglas | 6 (1.65) | 2 (1.12) | 4 (2.16) |

| Upper abdomen and liver | 2 (0.55) | 1 (0.56) | 1 (0.54) |

| Fallopian tube findings | |||

| Unilateral hydrosalpinx | 28 (7.71) | 18 (10.11) | 10 (5.41) |

| Bilateral hydrosalpinx | 48 (13.22) | 28 (15.73) | 20 (10.81) |

| Unilateral pyosalpinx | 2 (0.55) | 2 (1.12) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bilateral pyosalpinx | 1 (0.27) | 1 (0.56) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unilateral tubo-ovarian mass | 46 (12.67) | 26 (14.61) | 20 (10.81) |

| Bilateral tubo-ovarian mass | 22 (6.06) | 13 (7.30) | 9 (4.86) |

| Unilateral tubal block | 58 (15.97) | 30 (16.85) | 28 (15.14) |

| Bilateral tubal block | 148 (40.77) | 88 (49.44) | 60 (32.43) |

| Congested or hyperaemic tubes | 88 (24.24) | 43 (24.16) | 45 (24.32) |

| Dried and rigid tubes | 22 (6.06) | 14 (7.87) | 8 (4.32) |

| Encysted ascites | 39 (10.74) | 16 (8.99) | 13 (7.03) |

| Fluid filled pockets in pelvis | 42 (11.57) | 22 (12.36) | 20 (10.81) |

| Frozen pelvis | 14 (3.85) | 15 (8.43) | 9 (4.86) |

| Inability to see pelvis due to adhesions | 5 (1.65) | 4 (2.25) | 2 (1.08) |

Of the probable findings, the most common adhesions were seen as pelvic adhesions in 198 (54.54%), abdominal adhesions in 88 (24.24%) while, perihepatic adhesions (

Various probable fallopian tube findings of FGTB are shown in Table IV including unilateral hydrosalpinx (

Further analysis of data between two the time periods (July 2010 to December 2014 and January 2015 and July 2019 was done (Table IV). It was found that bilateral beaded tubes which were more common in the second half (P=0.05) and abdominal adhesions which were more common (29.12%) in the first half, than in the second half (19.45%) (P=0.03) and bilateral tubal block was more common in the first half (49.45%) than in the second half of time (32.43%; P=0.001). There was no significant difference in various laparoscopic findings across the two time periods.

Discussion

Female genital tuberculosis (FGTB) is a type of extrapulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) and is a significant cause of infertility, especially in developing countries3-7. Being a paucibacillary disease, its diagnosis remains a dilemma as the gold standard method of diagnosis like AFB positivity on microscopy or culture or positive Gene Xpert or epithelioid granuloma on endometrial and peritoneal biopsy are positive in selected cases and may miss the diagnosis in most cases5,7,9. The use of PCR picks up more cases but has a high false-positive rate and alone is not advisable to diagnose FGTB or to start anti-tuberculous therapy5,7,9.

The role of radiological methods such as ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography is more for tubercular tubo-ovarian masses and to differentiate between abdominopelvic TB and ovarian cancer, while hysterosalpingography can detect uterine and tubal pathophysiology15-18. Molecular tests like nucleic acids have been used for the diagnosis of pleural TB, a variant of EPTB and can be used for FGTB also19.

In the present study also, CRS was used for diagnosis of FGTB as it can pick up more cases which can be missed by gold standard culture and histopathology but avoid diagnosing FGTB by non-specific and highly false-positive tests like PCR.

Laparoscopy can detect more cases of genital TB and abdominal TB by direct viewing of the abdomen and pelvis for various TB findings. Definite findings like beaded tubes, caseous nodules or tubercles or probable findings such as encysted ascites, pelvic, abdominal or perihepatic adhesions, hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx or tubo-ovarian masses and tubal blockage are seen5,6,9,13,14.

Laparoscopy in suspected cases of FGTB should be done by an experienced gynaecologist after proper counselling of the patients due to complications in surgery20. All patients are treated with six months of anti-tubercular drugs as has been recommended by the WHO1, National TB Elimination Program of India2 and a previous randomized controlled trial21, which confirmed that six-months therapy was equally effective to nine month therapy. Rarely, multidrug-resistant FGTB can be there, necessitating longer treatment (18-24 months) therapy with reserved drugs in consultation with infectious disease experts22. Various other studies have also proven the utility of diagnostic laparoscopy alone or in combination with other molecular methods in better and early detection of FGTB23-30.

Tuberculosis has a major impact on both female and male fertility, but there are many controversies and pitfalls in its diagnosis29,30. However, laparoscopy appears to be a useful diagnostic modality in the diagnosis of FGTB along with other tests.

The strength and novelty of the study is the large sample size of successful cases of laparoscopy in FGTB patients diagnosed on CRS with the observation of various laparoscopic findings in abdominopelvic TB.

Furthermore, laparoscopy could detect most cases of FGTB missed by traditional methods for timely treatment to prevent permanent damage and sterility. The limitations of the study are dependence on CRS for diagnosis as laparoscopy may overdiagnose some cases, inability to do testing for pelvic infections like chlamydia or gonorrhoea due to financial and logistics constraints and also lack of long-term follow up data of these patients regarding improvement in fertility outcome with anti-tuberculous therapy.

In the current study, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed for all suspected and confirmed cases of FGTB as part of a research project and infertility protocol which is also a limitation as anti-tubercular treatment can be started on the basis of these tests without subjecting the patients to laparoscopy.

Overall, although laparoscopy is a useful method in diagnosing FGTB and abdominopelvic TB and, for prognostication of infertility, it should not be done in isolation, it should be combined with conventional methods as part of CRS for increased detection of FGTB for timely treatment.

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure Diagnostic laparoscopy showing (A) tubercles on uterus with peritubal and pelvic adhesions, (B) caseous nodules on peritoneum and abdominal adhesions, (C) perihepatic adhesions (Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome) with Sharma’s hanging gallbladder sign (arrow) and omental adhesions, (D) shaggy areas on the uterus and left-sided hydrosalpinx (arrow) with delayed spill on the right side, (E) hyperaemia and hydrosalpinx of the left fallopian tube, (F) large right-sided tubo-ovarian mass with caseous material coming out in a case of FGTB. FGTB, female genital tuberculosisAcknowledgment:

All faculty and residents of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department, AIIMS, New Delhi, are acknowledged for their assistance. Dr K. S. Sachdeva, Former Deputy Director General, Central TB Division & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and Dr Sangeeta Sharma, Professor & Head, National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases are acknowledged for guidance, Dr P. Vanamail is acknowledged for statistical inputs.

Financial support & sponsorship: This study received funding from Central TB Division and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (grant number RNTCP/IFB/GIA/NK/PL/2008-9/119).

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- WHO global tuberculosis report 2020. Geneva: WHO; 2020.

- New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2020.

- Genital tuberculosis: Current status of diagnosis and management. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:222-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of female genital tuberculosis, its risk factors and associated clinical features among the women of Andaman Islands, India: A community-based study. Public Health. 2017;148:56-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in diagnosis and management of female genital tuberculosis. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2021;71:476-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging progress on diagnosis and treatment of female genital tuberculosis. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female genital tuberculosis in light of newer laboratory tests: A narrative review. Indian J Tuberc. 2020;67:112-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of genital TB in infertile females in the era of molecular tests. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1538-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Xpert®MTB/RIF assay for extrapulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD012768.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Gene Xpert as compared to conventional methods in diagnosis of Female Genital Tuberculosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:247-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved diagnostic evaluation of suspected tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:325-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Index-TB guidelines: Guidelines on extrapulmonary tuberculosis for India. Indian J Med Res. 2017;145:448-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pelvic tuberculosis diagnosed during operative laparoscopy for suspected ovarian cancer. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2018 2018:6452721.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of role of transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound in diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2021;14:250-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computed tomographic findings in female genital tuberculosis tubo-ovarian masses. Indian J Tuberc. 2022;69:58-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pre treatment and post treatment positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) to evaluate treatment response in tuberculous Tubo-Ovarian masses. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;264:128-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female genital tuberculosis and infertility: Serial cases report in Bandung, Indonesia and literature review. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10:683.

- [Google Scholar]

- Challenges in pleural tuberculosis diagnosis: Existing reference standards and nucleic acid tests. Future Microbiol. 2017;12:1201-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased complication rates associated with laparoscopic surgery among patients with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;109:242-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Six months versus nine months anti-tuberculous therapy for female genital tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;203:264-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multi drug resistant female genital tuberculosis: A preliminary report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:108-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of genital tuberculosis: Correlation between polymerase chain reaction positivity and laparoscopic findings. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2016;5:3425-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laparoscopy in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in chronic pelvic pain. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2016;5:318-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of laparoscopic abdominopelvic and fallopian tube findings before and after antitubercular therapy in female genital tuberculosis with infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:215-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endoscopic findings of female egniatl tuberculosis: A 3 year analysis at a referral centre. Int J Gynecol End. 2018;2:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of female genital tract tuberculosis in suspected cases attending Gynecology OPD at tertiary centre by various diagnostic methods and comparative analysis. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2019;8:2286-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genital tuberculosis and its impact on male and female infertility. US Endocrinol. 2020;16:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controversies and pitfalls in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB with focus on genital tuberculosis. US Endocrinol. 2020;16:109-16.

- [Google Scholar]