Translate this page into:

Intravenous iron sucrose therapy for moderate to severe anaemia in pregnancy

Reprint requests: Prof. Alka Kriplani, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: kriplanialka@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is the most common nutritional deficiency in pregnancy. Prophylactic oral iron is recommended during pregnancy to meet the increased requirement. In India, women become pregnant with low baseline haemoglobin level resulting in high incidence of moderate to severe anaemia in pregnancy where oral iron therapy cannot meet the requirement. Pregnant women with moderate anaemia are to be treated with parentral iron therapy. This study was undertaken to evaluate the response and effect of intravenous iron sucrose complex (ISC) given to pregnant women with IDA.

Methods:

A prospective study was conducted (June 2009 to June 2011) in the department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. One hundred pregnant women with haemoglobin between 5-9 g% with diagnosed iron deficiency attending antenatal clinic were given intravenous iron sucrose complex in a dose of 200 mg twice weekly schedule after calculating the dose requirement.

Results:

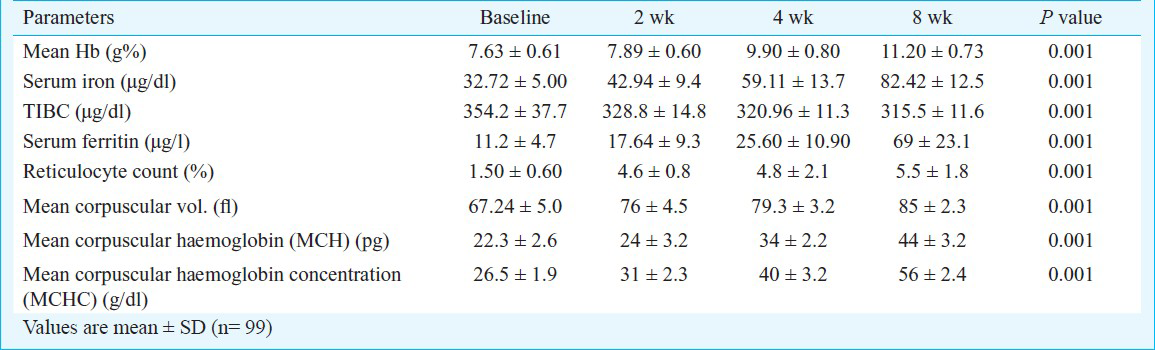

The mean haemoglobin raised from 7.63 ± 0.61 to 11.20 ± 0.73 g% (P<0.001) after eight wk of therapy. There was significant rise in serum ferritin levels (from 11.2 ± 4.7 to 69 ± 23.1 μg/l) (P<0.001). Reticulocyte count increased significantly after two wk of starting therapy (from 1.5 ± 0.6 to 4.6±0.8%). Other parameters including serum iron levels and red cell indices were also improved significantly. Only one woman was lost to follow up. No major side effects or anaphylactic reactions were noted during study period.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Parentral iron therapy was effective in increasing haemoglobin, serum ferritin and other haematological parameters in pregnant women with moderate anaemia. Intravenous iron sucrose can be used in hospital settings and tertiary urban hospitals where it can replace intramuscular therapy due to injection related side effects. Further, long-term comparative studies are required to recommend its use at peripheral level.

Keywords

Anaemia

iron deficiency

iron sucrose complex

parentral iron therapy

serum ferritin

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) is the most common nutritional deficiency in pregnant women. According to WHO, the prevalence of IDA is about 18 per cent in developed countries and 35-75 per cent (average 56%) in developing countries1. Globally, the prevalence of anaemia is 55.9 per cent with variations between developed and developing countries. In India, prevalence ranges between 33-89 per cent2. About half of the global maternal deaths due to anaemia occur in South Asian countries; India contributes to about 80 per cent of this mortality ratio3. Many programmes have been introduced and implemented to reduce the burden of anaemia in the country but the decrease is lower than other South Asian countries4. Various surveys [National Family Health Survey (NFHS), District Level Household Survey (DLHS), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Micronutrient Survey] have been conducted to calculate the prevalence of anaemia in India. During 10th Five Year Plan (2002-2007)4, a study conducted by ICMR5 showed that the prevalence of anaemia was highest among pregnant women (50-90%) and that of moderate (<8 g%) and severe anaemia (<5 g%) was persistently high. Prevalence was high in all States of the country with considerable variations in moderate to severe anaemia6. Other factors responsible for high incidence of anaemia in our country include early marriage, teenage pregnancy, multiple pregnancies, less birth spacing, phytate rich Indian diet, low iron and folic acid intake and high incidence of worm infections in Indian population7.

WHO defines anaemia as haemoglobin (Hb) <11 g %1 In India, the ICMR classification of iron deficiency anaemia is: 8-11 g% as mild, 5-8 g % as moderate and <5 g% as severe anaemia. In absence of interfering factors, serum ferritin <12-15 μg/l is considered as iron deficiency4.

The first choice for prophylaxis and treatment of mild iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy is oral iron therapy. But in patients with moderate and severe anaemia, oral therapy takes long time and compliance is a big issue in our country. Thus, pregnant women with moderate anaemia should be better treated with parentral iron therapy and/or blood transfusion depending upon individual basis (degree of anaemia, haemodynamic status, period of gestation, etc.).

Various parenteral iron preparations are available in the market which can be given either intravenously or intramuscularly. Initially, iron dextran and iron sorbitol citrate was started. But test dose was required to be given before these injections as severe anaphylactic reactions were reported with intravenous iron dextran. Iron sucrose has been reported to be safe and effective during pregnancy8. The injection can be given without test dose9.

A prospective study, therefore, was conducted in pregnant women with iron deficiency anaemia (haemoglobin between 5-9 g%) attending a tertiary care hospital in north India to evaluate the response and effect of intravenous (iv) iron sucrose complex (ISC) in terms of improvement in haemoglobin status and other parameters.

Material & Methods

The prospective study was conducted in the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India, from January 2009 to December 2010. A total of 111 women presenting in antenatal clinic with haemoglobin between 5-9 g% were screened, consecutively. Exclusion criteria were causes other than iron deficiency anaemia, multiple pregnancy, high risk for preterm labour and recent blood transfusions, thalasaemia and other medical disorders. About 8-10 ml blood was taken from each patient.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of blood was performed, and red cell indices, peripheral blood smear and detailed serum iron studies were also conducted. Seven women with causes of anaemia other than iron deficiency (four thalasaemia, one had sickle cell disease, one was haemolytic anaemia and one had chronic renal disease) were excluded. Two women did not consent for starting injectable iron therapy. Two refused for follow up so were excluded from study. Thus, 100 women were recruited for intravenous iron sucrose therapy. Ethical clearance for the study protocol was taken from the Ethics Committee of the institute. Informed written consent was taken from all the patients before starting the therapy. Baseline investigations including liver and kidney function tests, urine (routine microscopy and culture sensitivity), stool examination (for ova and cyst) were done. All women were given antihelmenthic therapy with tablet mebendazole 100 mg twice daily for three days. Folic acid tablets were given to all women during therapy.

The formula used for calculation of iron sucrose dose was as follows:

Required iron dose (mg) = (2.4 × (target Hb-actual Hb) × pre-pregnancy weight (kg)) + 1000 mg for replenishment of stores10.

The required iron dose varied depending upon index Hb level and pre-pregnancy weight. Average dose requirement was 1777 ± 168.5 mg (1400-2160 mg). Mean duration to complete total therapy was 4.5 ± 1.0 (3.5-5.5 wk).

Iron sucrose (Injection Orofer S, Emcure Pharmacueticals Limited, India) was given in a dose of 200 mg intravenously twice weekly in 200 ml normal saline over a period of 15-20 min. First dose was given in the ward where equipment for cardiopulmonary resuscitation was available. The following doses were given on outpatient basis. Patients were observed for side effects or anaphylactic reactions. Any minor or major side effects were documented. All parameters were repeated at 2 wk interval till 8 wk.

The primary outcome measures were haemoglobin and serum ferritin levels after 4 and 8 wk. Secondary outcome measures were improvement in serum iron levels, reticulocyte count, any adverse effects and perinatal outcome [period of gestation (POG) at the time of delivery, type of birth, postpartum haemorrhage, need of blood transfusion and foetal birth weight].

Statistical analysis: The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 15 (SPSS Inc., USA). Repeated measure analysis was done followed by post-hoc comparison by Benferroni method to see the trend of parameters with time. Confidence intervals (95%) of various proportions were also calculated. P<0.5 was taken as significant.

Results

The mean age of women was 27.8 ± 3.9 (range 21-34) yr and mean parity was 1.3; mean period of gestation (PDG) at the time of diagnosis was 25.69 ± 4.82 (14-32) wk. At the beginning, mean Hb was 7.63 ± 0.61 g%. Thirty two (32%) women had mild anaemia (>8 g%) and 68 per cent had moderate anaemia (5-7.9%). After completion of therapy, mean Hb raised to 11.20 ± 0.73 g%. Of the total women, 67 per cent achieved Hb ≥11 g%. The mean duration to achieve haemoglobin level more than 11 g% was 6.5 ± 2.3 wk. Table I shows the baseline haematological parameters and effect of iron sucrose therapy on all the parameters. Complete dosage schedule was done in 97 women. One woman was lost to follow up after five doses. Two delivered preterm before completion of all doses. One woman went into preterm labour and delivered at 32 wk after 6 doses and the second had preterm cesarean section because of pre-eclampsia and abruption at 33 wk (after 7 doses).

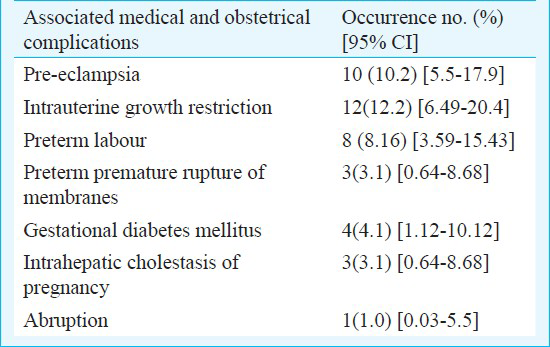

Peerintatal outcome: Ninety nine women were followed till delivery (one lost to follow up before term). Of these, nine (9%) delivered before 37 wk POG. Table II shows the associated antenatal complications in the enrolled women. The remaining 90 women delivered after 37 wk. Of these, 28 (31.2%) underwent emergency or elective cesarean section and the remaining 62 (68.8%) delivered vaginally. Mean period of gestation at delivery was 38.5 ± 1.0 (37-41) wk. Two (2.2%) women had postpartum haemorrhage (blood loss >500ml) and required blood transfusion. Intapartum and postpartum period of the remaining was uneventful. The mean birth weight of babies was 2762 ± 355 g.

Side effects: Five women complained of nausea and three had vomiting after first dose. One woman had diarrhoea after the second dose. One had thrombophlebitis after second dose, one had mild giddiness and restlessness at first dose which subsided spontaneously and did not recur on subsequent doses. Two women complained of mild fever after the first dose which did not recur on further dosing. One woman had hemetemesis after first dose. She was evaluated by the gastroenterologist and no cause was found. Iron sucrose was restarted after one week and she completed the full course without any further side effects. All other women well tolerated the injections. There was no major side effects and no allergic or anaphylactic reaction.

Discussion

The total requirement of iron during pregnancy is approximately 1000 mg (500 mg for developing foetus and placenta and similar amount for red cell increment)11. Usually, this iron is mobilized from iron stores. However, women with poor iron stores become iron deficient during pregnancy. Studies have shown that Hb levels <8 g% (moderate to severe anaemia) in pregnancy are associated with higher maternal morbidity31112. Hb less than 5 g% is associated with cardiac decompensation and pulmonary oedema. Blood loss of even 200 ml in third stage of labour can cause sudden shock and death in these women.

As compared to western women whose iron stores are sufficient and they need 30-40 mg elemental iron per day for anaemia prophylaxis in pregnancy1314, the stores in Indian women are deficient and they need 100 mg elemental iron per day for prophylaxis. For treatment of anaemia, dose recommended is 200 mg elemental iron per day14. In the present study, 5-9 g% Hb was taken as cut-off. Intravenous iron is superior to oral iron with respect to faster increase in Hb and faster replenishment of body iron stores15. Also, it reduces the need of blood transfusions16, and it can be given at outpatient basis.

In a study to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of intravenous iron sucrose with intramuscular iron sorbitol citrate, it was found that rise of Hb was more in intravenous group17. This study emphasized the superiority of iv iron therapy to intramuscular therapy in terms of rise of Hb and also safety profile.

Perewunsnyk et al18 studied 400 women who received a total of 2000 ampoules of iron sucrose. Minor general adverse effects including a metallic taste, flushing of the face and burning at the injection site occurred in 0.5 per cent cases. The high tolerance of the drug has been partly attributed to slow release of iron from the complex and also due to the low allergenicity of sucrose. Till date, one death has been reported with intravenous iron sucrose injection19. The explanation given for this was because of very slow infusion (1-2 h). The cause of death may be free radicals released from the iron sucrose. The injection should be given within 15-20 min or up to 200 mg can be given as slow iv push over 2-3 min. This case has not been mentioned in the literature but is available on clinical trial registry site19. In the present study, no major side effect was reported.

Breymann20 treated more than 500 antenatal women diagnosed with iron deficiency anaemia. Intravenous iron sucrose was given according to the calculated dose as either iv push over 5-10 min or iv infusion over 20-30 min. All injections were given on outpatient basis without any test dose. This study also emphasizes on the safety of iron sucrose injection. In the present study, the first dose was given in ward where facilities for emergency care were available. All subsequent doses were given on OPD basis. None of the patients required any emergency care. In other studies1721, target Hb for calculation of required dose has been taken 11 g/dl and for replenishment of stores 500 mg has been added. Keeping in mind very low iron stores in Indian women, we took 14 as index Hb and added 1000 mg for replenishment of stores. Even with this, maximum mean serum ferritin after 8 wk of starting therapy was 69 μg/l which is well within normal range. As compared to previous studies1720, ferritin levels in our study women showed a lesser increase. The reason can be due to severely depleted iron stores in Indian women.

Hookworm is one of the well established causes of anaemia in developing countries. Routine antihelminthic therapy in pregnancy is not recommended. But due to high prevalence in developing countries including India, it is advisable to give antihelminthic therapy to pregnant women presenting with anaemia21.

A study conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of iron sucrose in dialysis patients who were sensitive to iron dextran, demonstrated the safety of iv iron sucrose injections22.

In a study to assess and compare the efficacy of two and three doses of intravenous iron sucrose with oral iron therapy, there was higher frequency of responders (Hb>11g%) in intravenous group (75 vs. 80%). There was a significant difference of repleted iron stores before delivery (ferritin >50 mg/l) in the group with three intravenous iron doses in comparison to the oral iron group (49 vs. 14%; P<0.001). No differences were observed in maternal and perinatal outcomes. The study did not conclude any significant benefit of parentral iron therapy over oral iron therapy23. However, in practice, noncomplaince is very common with oral iron therapy.

Drawbacks of our study was lack of control group (intramuscular iron therapy) and non-randomised trial. Large randomized controlled trials are required to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous iron sucrose complex over intramuscular iron therapy.

In conclusion, our results showed that intravenous iron sucrose therapy was effective to treat moderate anaemia in pregnant women. Intramuscular preparations are known to be associated with local side-effects. Iron sucrose complex iv therapy was with negligible side effects. It caused rapid rise in haemoglobin level and the replacement of stores was faster. Long term comparative studies are required to assess if it can be used at peripheral level.

References

- Anaemia in pregnancy. In: Text book of obstetrics including perinatology & contraception (6th ed). Calcutta: New Central Book Agency (P) Ltd; 2004. p. :262-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of anemia among pregnant women and adolescent girls in 16 districts of India. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:311-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence & consequences of anaemia in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:627-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Planning Commission. Government of India. Tenth Five- Year Plan 2002-2007. Sectoral Policies and Programmes. 2002. Nutrition. New Delhi: Government of India; Available from: Planningcommission.nic.in/plans/planrel/fiveryr/10th/10defaultchap.html

- [Google Scholar]

- DLHS on RCH. Nutritional status of children and prevalence of anaemia among children, adolescent grils and pregnant women 2002-2004. Available from: http://www.rchindia.org/nr_india.htm 2006

- [Google Scholar]

- Micronutrient profile of Indian population. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of iron sucrose for iron deficiency in patients with dialysis-associated anemia: North American clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:300-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron deficiency and other hypoproliferative anemias. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, eds. Harrison's textbook of internal medicine (17th ed). New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. p. :628-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO Joint Expert Consultation Report. Requirements of vitamin A, iron, folate and vitamin B12 (FAO Food and Nutrition series 23) Rome: FAO; 1988.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron prophylaxis in pregnancy - general or individual and in which dose? Ann Hematol. 2006;85:821-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron prophylaxis during pregnancy - how much iron is needed? A randomized dose- response study of 20-80 mg ferrous iron daily in pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:238-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaemia during pregnancy and treatment with intravenous iron: review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;110:2-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supplementing iron intravenously in pregnancy. A way to avoid blood transfusions. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:99-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study - Efficacy, safety and compliance of intravenous iron sucrose and intramuscular iron sorbitol in iron deficiency anemia of pregnancy. JPMA. 2002;52:392-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Parenteral iron therapy in obstetrics: 8 years experience with iron-sucrose complex. Br J Nutr. 2002;88:3-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of iron sucrose complex for anemia in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:S28-S31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hookworm-related anaemia among pregnant women: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of iron sucrose in patients sensitive to iron dextran: North American clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:88-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iron prophylaxis in pregnancy: Intravenous route versus oral route. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144:135-9.

- [Google Scholar]