Translate this page into:

High prevalence of alcohol use disorder & psychiatric comorbidity among coal mine workers: Observations from a cross-sectional study in West Bengal

For correspondence: Dr Amit Chakrabarti, ICMR-Centre for Ageing & Mental Health (ICMR-CAMH), Kolkata 700 091, West Bengal, India e-mail: amit.chakrabarti@gov.in

-

Received: ,

Abstract

Background & objectives

Tobacco (30%), alcohol (21.4%) and cannabis (3%) are the three most commonly abused substances in India. Tobacco and alcohol abuse have higher prevalence rates among different occupational groups as compared to that in general population in the country. Both tobacco and alcohol lead to significant occupational harm in terms of absenteeism, injuries, sickness and lost productivity. This study estimated the patterns of substance use and associated common psychiatric comorbidity in a sample of coal mine workers.

Methods

Coal mine workers at the age of 18 yr or above engaged in mining activities (skilled/semi-skilled/unskilled) were recruited from the Raniganj – Asansol coal mining areas of Eastern Coalfields Limited (ECL). Participants were screened to identify patterns of substance use and other common mental health problems. All participants were administered ASSIST (The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test); GENACIS (Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study) modified questionnaire; and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for primary screening for anxiety and depression.

Results

Out of 202 participants 69 per cent (n=140) were found with either ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk); or ‘dependent’ (high risk) patterns of use of either tobacco or alcohol or cannabis or of more than one substance. Only 31 per cent (n=62) were ‘low-risk’ for all substances. Almost 65 per cent (n=132) and 49 per cent (n=99) participants out of the whole sample (n=202) belonged to ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk) and ‘dependent’ (high risk) pattern of tobacco and alcohol consumption, respectively. About 28.8 per cent (n=38) and 23.7 per cent (n=31) of all participants had anxiety and depression, respectively. Combined moderate to high use of both alcohol and tobacco use was significantly associated with the risk of having anxiety [adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=4.896, P<0.015] and depression (AOR=5.335, P<0.012).

Interpretation & conclusions

Alcohol and tobacco are major substance abuse problems among coal mine workers. This population requires early community and primary care based brief intervention as well as additional community-based pharmacotherapy for substance dependence problems as well as intervention for common mental health issues.

Keywords

Mental health

alcohol use disorder

ASSIST

coal mine workers

anxiety

depression

tobacco

Mental health is an under-recognized and under-served area in occupational health in India. Tobacco (30%), alcohol (21.4%) and cannabis (3%) are three most commonly abused substances prevalent in India1,2. Compared to their use in general population, tobacco and alcohol use have higher prevalence rates among different occupational groups in India; about 47 to 70 per cent for all forms of tobacco across genders and 30 to 50 per cent for alcohol3,4. An approximate economic burden of harmful alcohol use in India measured in 2003–2004 was INR 244 billion, which significantly exceeded the total excise revenue of INR 216 billion generated countrywide during the same period4 and 70 per cent of the economic cost of alcohol abuse could be attributed to a loss in productivity5.

The coal industry in India is one of the largest industrial sectors, and Coal India Limited is the highest coal producer in the world, with a turnover of INR 80,000 crore and a worker strength of ∼3,60,000. However, regular consumption of tobacco and alcohol among workers engaged in mining activities (about 83% of workforce) is higher compared to that in other occupational groups (almost 40%) increasing to almost 70 per cent among workers with occupational injuries6.

WHO-ASSIST (World Health Organization – The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test) an eight-question tool is an internationally validated screening tool for patterns of substance use including tobacco, alcohol and cannabis. It provides an accurate measure of patterns of substance use across gender, age and culture. ASSIST is designed for administration by primary care workers7 and contains eight questions about lifetime and past three months of substance use.

Therefore, to generate evidence on the problem of alcohol and other substance use among coal mine workers, this study aimed to use ASSIST screening. Furthermore, this study aimed to identify other co-existing common mental health problems in this population, particularly anxiety and depression by using validated tools.

Material & Methods

This was a cross-sectional study in design undertaken at ICMR-Centre for Ageing & Mental Health (ICMR-CAMH), Kolkata (previously Regional Occupational Health Centre, Eastern) after obtaining the approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. The duration of the study was from December 2016 till March 2019.

Study setting

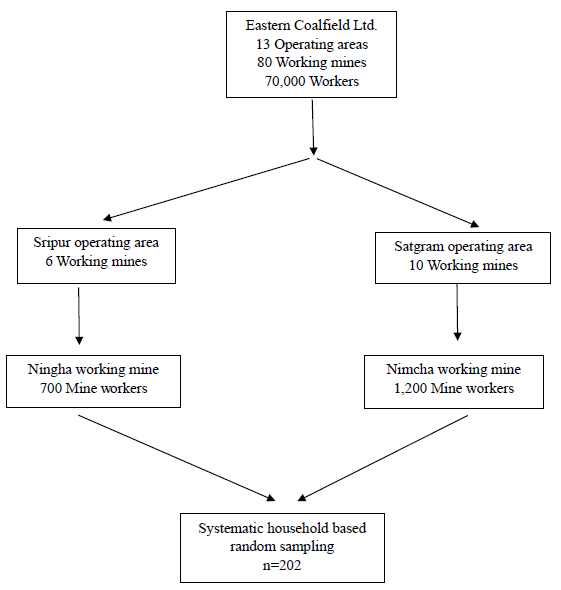

This study was implemented in the Asansol – Raniganj area of Eastern Coalfields Limited (ECL); a subsidiary of Coal India Ltd. The mining areas of ECL, distributed over ∼750 sq. km., have 13 operating areas and 80 working mines with a worker strength of ∼70,000. For the sake of convenience and following discussion with officials of ECL, two operating areas, i.e., Satgram (working mines 10) and Sripur (working mines 6) were identified based on accessibility and number of workers available. Two mines from two areas i.e., Ningha from Sripur area and Nimcha from Satgram were selected for implementation of this study (Figure).

- Flow diagram showing selection of the participants.

Study population

Coal mine workers engaged in mining activities (skilled/semi-skilled/unskilled) ≥ 18 yr of age were recruited from Ningha and Nimcha working mines. Participants were directly engaged in mining activities and hence the population included only male workforce. The total number of coal mine workers in Ningha and Nimcha working mines was 700 and 1,200, respectively, of which the participants were recruited.

Study sample size

Estimates of coal mine workers in the Nimcha colliery (Satgram area, ECL) and Ningha colliery (Sripur area, ECL) are ⁓1,200 and 700, respectively. Available evidence suggests that tobacco (30%), alcohol (21.4%) and cannabis (3%) are the three most common substances of abuse prevalent in India. We considered alcohol as the most likely problem substance among coal mine workers with an assumption of a prevalence of at least 20 per cent. Therefore, to detect a minimum of 20 per cent prevalence of alcohol use in a population size of 1,900 at 95% confidence interval (CI), we needed to screen at least 218 persons. The recruitment target, therefore, was n=220 coal mine workers.

Study sample recruitment

Recruitment was carried out by systematic household-based random sampling, e.g., visiting every 3rd or 5th household. As coal mine workers live in ECL housing in mine adjoining areas, a list of the mine workers along with their residences was collected locally with the help of ECL workers. Household-based screening was carried out by trained project staff who were accompanied and assisted by support staff from ECL management. Only permanent workers were recruited as participants for the study. To ensure the availability of participants, the project staff, accompanied by a local support workforce, visited the households to enquire about the presence of the workers. If the worker was absent in the 3rd household, the project staff went to the 5th; if the worker was available in the 3rd, the following 3rd household was visited. Primary screening and subsequent ASSIST screening and other assessments were carried out by trained project staff, assisted by technical staff of the institute. All project staff received adequate training on the assessment of substance use problems along with the confidentiality and social issues involved in such investigations. During primary screening, the age of a worker was verified, and the following questions were asked:

-

(i)

Have you consumed alcohol, cannabis in any form (eaten/beverage/smoked) and/or tobacco (smoked/smokeless) in any form during the past year?

-

(ii)

Have you consumed alcohol, cannabis in any form (eaten/beverage/smoked) and/or tobacco (smoked/smokeless) in any form during the past 30 days?

Any worker responding ‘yes’ to both questions for any or more than one substance was briefed about the study and recruited following completion of the signed informed consent procedure. Workers recruited to participate in the study were, in general, advised to complete subsequent assessments on the same day. However, some workers, having urgencies of shift-work-schedule, were advised to come the following day. In general, same project staff engaged in informed consent and recruitment of a particular participant, completed the full assessment upon recruitment. Any worker responding ‘no’ to any of the initial two questions was not included in the study and was provided general health advice.

Study methodology

Study procedures were conducted in the households of workers/local dispensaries during off-duty hours of the participants as desired by the participants to ensure privacy of the assessment. On recruitment, all participants were administered the following procedure:

-

ASSIST, an eight-question internationally validated tool for screening of ‘abstinent and low-risk’; ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk); or ‘dependent’ (high risk) patterns of use. A validated Hindi version of the instrument was available.

Patterns of use were defined by ASSIST score in the following manner.

‘Low-risk’ – Score 1 to 3 for tobacco and cannabis; and 1 to 10 for alcohol.

‘Hazardous and harmful’ – Score 4 to 26 for tobacco and cannabis; and 11 to 26 for alcohol.

‘Dependent’ – Score 27 and above for all (tobacco, alcohol and cannabis).

Socio demographic instrument: Integrated in modified GENACIS (Gender, Alcohol and Culture: An International Study) questionnaire8 including socio demographic, economic (e.g., monthly income), family and socio-cultural information, work hours and levels of work-related stress.

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS): This instrument designed to identify both anxiety and depressive disorders has been used extensively in clinical and research studies and validated in a number of Indian languages9.

Statistical analysis

All research data were collected on pen and paper and by face-to-face interviews with the participants. Data were initially entered in MS Excel and cleaned. Socio demographic information, viz., level of education and monthly earnings were categorized. Chi square test was used to show the association between categorical variables, viz., levels of alcohol and/or tobacco use with anxiety or depression. Binary logistic multivariable regression was used for risk assessment to identify whether alcohol and/or tobacco use can predict anxiety or depression. Multivariable regression was adjusted for age and income level. Omnibus Chi-square test and Hosmer Lemeshow statistics were used to check model fitness. P≤0.05 was considered as significant at 5% level of significance. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The manuscript was prepared in conformity with the STROBE-guidelines for reporting observational studies10.

Results

These study sites were at an approximate distance of 200 km from Kolkata, the capital city of West Bengal and the investigation was conducted among coal mine workers in the Nimcha colliery (Satgram area, ECL) and Ningha colliery (Sripur area, ECL). Both sites had a stable population base with insignificant in or out-migration. Till the completion of the study up to March 2019, 202 coal mine workers were recruited and screened by ASSIST. Following screening by ASSIST 69 per cent (n=140) were found with either ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk); or ‘dependent’ (high risk) patterns of use of either tobacco or alcohol or cannabis or more than one substance. Only 31 per cent (n=62) were ‘low-risk’ for all substances and were provided with general medical advice including advice to remain at a ‘low-risk’ level for substance use.

All participants were males aged 25 to 58 yr, and the mean age was 46 yr (± standard deviation). Most subjects (about 60%) were illiterate or had only primary education; however, the children of most participants (81%) had either completed school or were currently going to school. The median monthly earnings of workers was INR 35,000, with a range of INR 8,000 to 60,000, and most (88%) had more than one asset in their households. Use of liquid petroleum gas (LPG) (47%) and coal (48%) for cooking were reported by an almost equal proportion of the participating workers.

In screening by ASSIST for patterns of tobacco consumption (both smokeless and smoked), 65 per cent (n=132) participants of 202 belonged to ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk) and ‘dependent’ (high risk) pattern of consumption. However, about 18 per cent (n=36) participants had only tobacco as the major substance use problem.

Regarding alcohol consumption almost 49 per cent (n=99) workers had ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk); or ‘dependent’ (high risk) pattern of consumption; 3 participants (1.5%) had only alcohol as the major substance problem.

Only 13 (6.4%) workers were identified with cannabis use with 4.45 per cent (n=9) in ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk) category and 2 per cent (n=4) were in ‘dependent’ (high risk) category.

When combined substance use was considered, the most common pattern was combined ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk) or ‘dependent’ (high risk) use of alcohol and tobacco: 31 per cent (n=63) followed by combined moderate to high risk use of alcohol, tobacco and cannabis: 5.45 per cent (n=11).

Screening for anxiety and depression by HADS was conducted to assess the possibility of psychiatric comorbidity among the coal mine worker participants. Anxiety and depression were analyzed upon 132 and 131 participants, out of 202 participants, respectively including all categories, i.e., ‘low-risk, ‘hazardous and harmful’ (moderate risk); or ‘dependent’ (high risk) following adjustment for missing data. Almost 28.8 per cent (n=38) out of 132 participants with any category of alcohol and/or tobacco use as screened by ASSIST were identified with anxiety that included both moderate and high levels of anxiety. Out of the 38 participants who had anxiety, 52.6 per cent (n=20) were moderate to high-risk users of both alcohol and tobacco, while among workers with low risk to both alcohol and tobacco, anxiety was recorded only in 13.2 per cent (n=5). This association was found to be significant both in bivariate and multivariable analysis. Odds of having anxiety was 4.048 times (P=0.029) and 4.896 times (P=0.015) more among participants having moderate to high risk for either alcohol or tobacco use and moderate to high risk for combined alcohol and tobacco use, respectively in comparison with low risk of substance problem (both alcohol and tobacco). Majority of the participants having anxiety (64.3%) had monthly income level less than INR 33,000 and half of the participants (50%) with anxiety were less than 45 yr of age. No significant difference was observed between anxiety with income level and age group (Table I).

| Variables | Anxiety | Bivariate | Multivariable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Absent (n=94), n (%) |

Present (n=38), n (%) |

Total (n=132), n (%) |

Pearson’s chi-square test, P value | OR |

95% CI Lower - Upper |

P value | OR |

95% CI Lower - Upper |

P value | |

| Alcohol & tobacco | ||||||||||

| Both low | 43 (45.7) | 5 (13.2) | 48 (36.4) |

12.728, 0.002 |

Ref | Ref | ||||

| Any substance (moderate to high) | 23 (24.5) | 13 (34.2) | 36 (27.3) | 4.861 | 1.541 - 15.336 | 0.007 | 4.048 | 1.156 - 14.17 | 0.029 | |

| Both (moderate to high) | 28 (29.8) | 20 (52.6) | 48 (36.4) | 6.143 | 2.066 - 18.26 | 0.001 | 4.896 | 1.355 - 17.687 | 0.015 | |

| Income (INR) | ||||||||||

| <33000 | 67 (78.8) | 18 (64.3) | 85 (75.2) |

2.388, 0.122 |

Ref | Ref | ||||

| >33000 | 18 (21.2) | 10 (35.7) | 28 (24.8) | 2.068 | 0.814 - 5.251 | 0.126 | 1.057 | 0.364 - 3.069 | 0.919 | |

| Age group (yr) | ||||||||||

| >45 | 55 (59.1) | 19 (50) | 74 (56.5) | 0.917, 0.388 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| <45 | 38 (40.9) | 19 (50) | 57 (43.5) | 1.447 | 0.678 - 3.09 | 0.339 | 1.513 | 0.597 - 3.833 | 0.382 | |

Ref, reference; INR, Indian rupees; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

Among 131 participants, 23.7 per cent (n=31) were recorded to have depression. Out of the total participants who were depressed, 61.3 per cent (n=19) were in the moderate to high risk for combined alcohol and tobacco use category. Again, among workers with low risk to both alcohol and tobacco depression was only 16.1 per cent (n=5). Combined moderate to high use of both alcohol and tobacco use emerged as risk for having depression [adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=5.335, P<0.012] compared to both low level of alcohol and tobacco use. About 65.2 per cent and 44.8 per cent of participants having depression had income level less than INR 33,000 and belonged to age group of more than 45 yr respectively. No significant association was found between depression with income level and age group (Table II).

| Variables | Depression | Bivariate | Multivariable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Absent (n=100), n (%) |

Present (n=31), n (%) |

Total (n=131), n (%) |

Pearson’s chi-square test, P value | OR |

95% CI Lower - Upper |

P value | OR |

95% CI Lower - Upper |

P value | |

| Alcohol & tobacco | ||||||||||

| Both low | 42 (42) | 5 (16.1) | 47 (35.9) |

11.503, 0.003 |

Ref | Ref | ||||

| Any substance (moderate to high) | 29 (29) | 7 (22.6) | 36 (27.5) | 2.028 | 0.586 - 7.016 | .264 | 1.456 | 0.346 - 6.125 | 0.608 | |

| Both (moderate to high) | 29 (29) | 19 (61.3) | 48 (36.6) | 5.503 | 1.845 - 16.416 | .002 | 5.335 | 1.442 - 19.731 | 0.012 | |

| Income (INR) | ||||||||||

| <33000 | 69 (77.5) | 15 (65.2) | 84 (75) |

1.477, 0.224 |

Ref | Ref | ||||

| >33000 | 20 (22.5) | 8 (34.8) | 28 (25) | 1.84 | 0.682 - 4.962 | .228 | 0.861 | 0.267 - 2.781 | 0.803 | |

| Age group (yr) | ||||||||||

| >45 | 60 (60.6) | 13 (44.8) | 73 (57) |

3.34, 0.068 |

Ref | Ref | ||||

| <45 | 39 (39.4) | 16 (55.2) | 55 (43) | 2.13 | 0.939 - 4.834 | .070 | 1.471 | 0.542 - 3.993 | 0.449 | |

Discussion

This study presents observations regarding patterns of common substance use behaviour among coal mine workers in West Bengal. Alcohol and tobacco were major substance use problems among coal mine workers. Although this study had a small sample size, the prevalence rates for both tobacco and alcohol problems among coal mine workers are much higher than that observed in the general population, viz., 20.9 per cent prevalence of tobacco use disorders and a national prevalence rate of 4.7 per cent of alcohol use disorder among Indian adults identified by National Mental Health Survey 2015-201611.

Alcohol and other substance use, particularly among different occupation groups, is an under-investigated area in the Indian context, although the health and economic consequences of the same are significant. Available evidence from the country does not report a systematic and robust investigation on alcohol and substance use problems among coal mine workers in India. Reported findings include presence of alcohol use (20%) and tobacco smoking (60%) among stone mine workers in Rajasthan12 and a higher risk of injury among underground coal miners who consume alcohol6. Internationally the evidence base is more robust and comparable to our findings with a cross-sectional study from Mongolia reporting a 22.1 per cent alcohol use among mine workers vs. the national prevalence rate of 15.5 per cent13. An Australian study among metal mine workers assessed alcohol use among workers with WHO validated Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and identified a 94.8 per cent alcohol use among males and 92.1 per cent use among females in past 12 months14. Additionally, a study from Ukraine identified that current drinkers have a higher chance of engagement in a high-risk profession like coal mining15. The population with moderate to high-risk alcohol use is expected to benefit most from early community or primary care based brief intervention with add on pharmacotherapy.

Combined moderate to high use of both alcohol and tobacco use emerged as risk for having anxiety and depression compared to both low risk of alcohol and tobacco use. In addition, odds of having anxiety is 4.048 times higher among participants having moderate to high risk use of either alcohol and tobacco when compared to low risk of alcohol and tobacco use. Similar observations have also been reported from a study among Chinese coal mine workers with detection rates of anxiety higher among workers with drinking habit16. A study among Brazilian coal miners, however, reported low rates of depression and 13 per cent prevalence of low or moderate anxiety17. On the contrary, among Asian population, among Chinese coal mine workers, a study using Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale identified incidence of anxiety and depression as 51.1 per cent and 60.5 per cent respectively16. Tobacco is evidenced to possibly have a bidirectional relationship with anxiety or depression with smoking behavior leading to later onset of anxiety/depression or vice versa18. Similarly alcohol use disorders are known to co-exist at a higher rate among persons with an anxiety disorder or other behavioral disorder19.

Therefore, our findings not only strengthen the need for community and primary care-based intervention for tobacco and alcohol use disorders among coal mine workers, but further expand the scope of the study to further investigate and intervene for co-morbid common mental health problems.

The resources and time available with the study team did not permit covering a wider representation of the entire coal miner workforce of the Eastern Coalfields Ltd under the present investigation. Our inquiry on mental health comorbidity was limited only to anxiety and depression and we could not include other relevant mental health morbidities. The broad objective of this investigation was to identify whether the study population had a considerable problem of alcohol and other substance use and associated common mental health comorbidities. However, this study was not powered enough to look into the sociocultural determinants to identify the interactions and mediations to investigate further the pathways of substance use disorders and mental health comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge Prof. Malay K. Ghosal (Medical College, Kolkata) for guidance and inputs; Director (Personnel). Drs B. Guha (Chief Medical Services), S.K. Sinha (CMO), M.M. Samantaray (Ex-Chief, Medical Services), R.R.K. Singh (AMO, Sripur Area), T. Dutta (AMO, Satgram Area), J. Mukherjee (Medical Superintendent & Project Coordinator on behalf of ECL), S.P. Chakraborty (Central Hospital, Kalla), R.C. Soren, P. Ranjan, Mr. B. Mishra, Mr. I. Paswan and Ms. Arati Bauri (ECL) for assistance, coordination, organization and support. Dr. S. Chatterjee (Asansol District Hospital) for assistance and support and Mr. K. Nayak [ROHC (E)] for field work.

Financial support & sponsorship

This study was funded by an intramural grant received from the ICMR-National Institute of Occupational Health (ICMR-NIOH), Ahmedabad.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- The extent, pattern and trends of drug abuse in India: national survey/United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. New Delhi: Regional Office for South Asia; 2004.

- Tobacco use in India: Prevalence and predictors of smoking and chewing in a national cross sectional household survey. Tob Control. 2003;12:e4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social disparities in tobacco use in Mumbai, India: The roles of occupation, education, and gender. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1003-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol related harm: Implications for public health and policy in India. Bangalore, India: Publication No 73, NIMHANS; 2011.

- Investing in mental health. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42823/9241562579.pdf?sequence=1, accessed on November 12, 2023.

- Relationships of job hazards, lack of knowledge, alcohol use, health status and risk-taking behavior to work injury of coal miners: a case-control study in India. J Occup Health. 2008;50:236-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487-500.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cross-cultural adaptation into Punjabi of the English version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National mental health survey of India, 2015-16: Prevalence, patterns and outcomes. Bengaluru, India: Publication no. 129, NIMHANS; 2016.

- Sociodemographic profile, work practices, and disease awareness among stone mine workers having silicosis from central Rajasthan. Lung India. 2023;40:117-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Non-communicable disease risk factors among a cohort of mine workers in Mongolia. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61:1072-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol consumption in the Australian mining industry: The role of workplace, social, and individual factors. Workplace Health Saf. 2021;69:423-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol use, depression, and high-risk occupations among young adults in the Ukraine. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:948-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety and depression status of coal miners and related influencing factors. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2018;36:860-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health in underground coal miners. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2018;73:334-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;19:3-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Association of lifetime mental disorders and subsequent alcohol and illicit drug use: Results from the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:280-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]