Translate this page into:

High fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) receptor surface expression predicts poor outcome in FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) negative patients in adult acute myeloid leukaemia: a prospective pilot study from India

Reprint requests: Dr Sameer Bakhshi, Department of Medical Oncology, Dr B.R.A. Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: sambakh@hotmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Mutations in fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) receptor have significant role in assessing outcome in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Data for FLT3 surface expression in relation to FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) status and outcome are not available from India. The objective of the current study was to investigate adult patients with AML for FLT3 expression and FLT3 ITD mutation, and their association with long-term outcome.

Methods:

Total 51 consecutive de novo AML patients aged 18-60 yr were enrolled in the study. FLT3 ITD was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); flowcytometry and qPCR (Taqman probe chemistry) were used for assessment of FLT3 protein and transcript, respectively. Kaplan Meier curves were obtained for survival analysis followed by log rank test.

Results:

FLT3 ITD was present in eight (16%) patients. Complete remission was achieved in 33 (64.6%) patients. At 57.3 months, event free survival (EFS) was 26.9±6.3 per cent, disease free survival (DFS) 52.0±9.2 per cent, and overall survival event (OS) 34.5±7.4 per cent. FLT3 surface expression was positive (>20%) by flow-cytometry in 38 (88%) of the 51 patients. FLT3 surface expression and transcripts were not associated with FLT3 ITD status. FLT3 expression was significantly associated with inferior EFS (P=0.026) and OS (P=0.018) in those who were negative for FLT3 ITD.

Interpretation & conclusions:

This study evaluated FLT3 ITD mutation along with FLT3 expression in AML patients, and associated with survival. Negative impact of FLT3 surface expression on survival was observed in AML patients who were FLT3 ITD negative.

Keywords

Acute myeloid leukaemia

FLT3 ITD

flowcytometry

PCR

prognosis

The fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a type III receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) expressed on the surface of haematopoietic stem cells and plays vital role in normal haematopoiesis. FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) is associated with increased transcript level of FLT3 in adult acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)12.

FLT3 expression elevates proliferation in myeloblasts and mitigates their apoptosis, whereas the relationship between the signal cascades through FLT3 is unclear in leukemogenesis. FLT3 ITD mutations have proven association with inferior survival outcome and are, therefore, applied in risk stratification3. A few studies from Indian subcontinent have shown that FLT3-ITD is observed in 7-25 per cent of AML patients45678. However, data with regard to FLT3 surface expression in AML patients in relation to FLT3 ITD status and survival outcome from India are lacking.

In the current study, we prospectively evaluated FLT3 ITD mutation and FLT3 expression by flowcytometry and real time PCR in adult patients with AML, and correlated the same with the outcome.

Material & Methods

Total 51 consecutive de novo AML patients > 18 and < 60 yr of age (inclusion criteria) were prospectively enrolled from the department of Medical Oncology at Dr. B. R. A. Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital at All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, from March 2008 to June 2010. Acute promyelocytic leukaemia patient were excluded. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics committee, and an informed written consent was taken prior to sampling. Five ml peripheral blood (N=32 patients, if peripheral blast count was more than 30%) or otherwise 5 ml bone marrow (N=19 patients) was collected in EDTA coated sterile vacutainer. AML was classified into good, intermediate and poor risk cytogenetic groups as per standard criteria9.

Induction therapy consisted of daunorubicin 60 mg/m2/days for three days with cytarabine 100 mg/m2/day for seven days; patients who were not in remission post first induction received cytarabine 100 mg/m2 slow intravenous push twice daily for 10 days, daunorubicin 50 mg/m2/day for three days and etoposide 100 mg/m2/day for five days. Patients who were not in complete remission (CR) after second induction were declared refractory. Post CR, patients received three cycles of cytarabine at 18 g/m2.

FlT3 ITD mutation detection: FLT3 ITD was screened by amplification of the mutated gene by PCR using specific primers. DNA was isolated from 5×106 cells using DNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Crawley, UK) The quality and quantity of DNA were analyzed by NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo scientific, USA). Total 150 ng DNA was used for FLT3 internal tandem duplication was detected by PCR using the following primers5: Forward -5’-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCAGAACTGCCTATTCCTA-3’ and Reverse -5’- CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC CTGTCCTTCCACTATACTGT- 3’ with 35 cycles and annealing temperature 53°C. Finally, the PCR product was resolved on 3.5 per cent agarose gel.

Flow cytometry: Mononuclear cells (MNCs) separated (using density gradient media) from peripheral blood/bone marrow were evaluated for FLT3 surface expression (CD135) on dim CD45 positive cells. Total 20,000 events were acquired and analyzed using FACS Calibur flow-cytometer and cell quest pro software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, USA).

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR): Total RNA was isolated from 10 million MNCs using TRIzol method5. RNA was evaluated for quality and quantity by spectrophotometry. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg aliquots of total RNA in a 20 μl standard reaction mixture using reverse transcription (RT) kit (Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany). Absolute quantification of FLT3 transcripts was done by qPCR using TaqMan probe chemistry (Light Cycler 2.0). Standard was prepared using cloned quantified plasmids of FLT3 amplicon (Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany). Different concentrations ranging from 102-108 copies of plasmid were prepared using serial dilution and four different concentrations were used in duplicate for standard curve preparation. Standards with known copies of plasmid were used in all experiments for normalization and quantification. Beta actin was used as housekeeping gene.

Statistical analysis: Data were expressed as median (range) and mean ± SD. The end point for the survival data was December 31, 2012. The differences between the values were determined by using Kruskal Wallis test and independent Student's t test, respectively. Median values of the quantitative variables were used as a cut-off point for categorization into high or low expression. Outcome analysis was assessed based on event free survival (EFS), disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). EFS was defined as time between the diagnosis and the first event such as failure to achieve complete remission, relapse or death. DFS was defined as the time from CR until relapse or the date of last follow up. OS was defined as time between the diagnosis and the death or the last follow up. Kaplan Meier curves were obtained for survival analysis followed by log rank test. All statistical analysis was done using STATA 11.0 (Stata Corp LP, Texas, USA).

Results

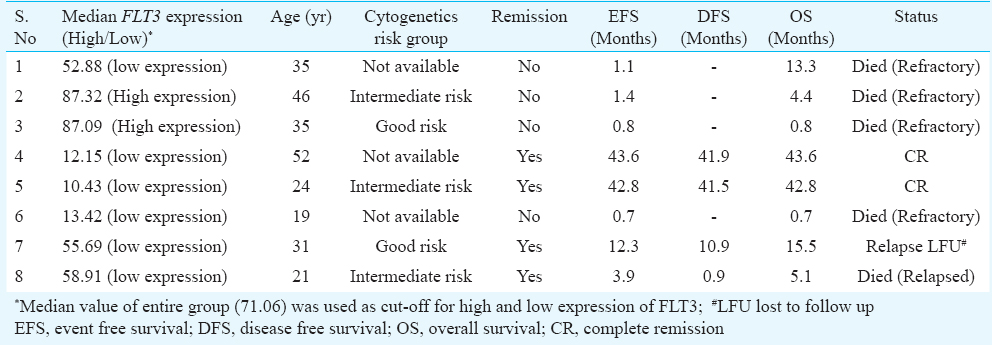

FLT3 ITD was present in eight (16%) patients. None of the baseline patients characteristics was associated with FLT3 ITD. The median WBC count in FLT3 ITD positive patients was three times higher as compared to patients whose blasts were negative for FLT3 ITD (Table IB). CR was achieved in 33 (64.6%) patients. For all 51 patients at 57.3 months, EFS was 26.9±6.3 per cent, DFS 52.0±9.2 per cent, and OS 34.5±7.4 per cent. FLT3 ITD status did not predict EFS, DFS and OS (Table IC).

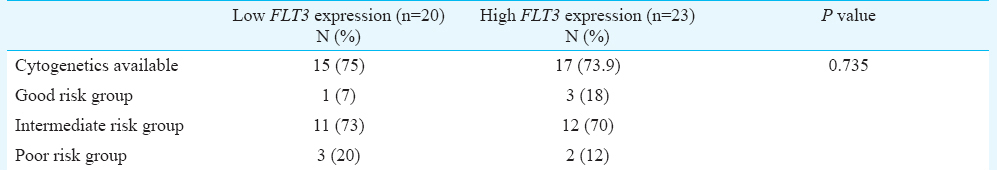

FLT3 expression in relation to FLT3 ITD status and outcome: FLT3 surface expression was positive (> 20% expression) by flow-cytometry in 38 (88%) FLT3 ITD negative patients and median expression of the total patients was 71.0 per cent (range: 3.63-99.66%). FLT3 surface expression and transcripts were not associated with FLT3 ITD status (Table IA).

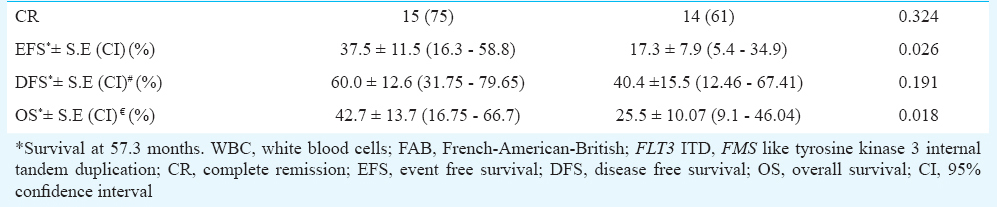

FLT3 ITD positive and negative patients were grouped according to FLT3 surface expression above and below median. In FLT3 ITD positive subgroup high FLT3 expression did not predict survival (Fig. 1A-C) (Table II). In FLT3 ITD negative subgroup, FLT3 expression was not associated with cytogenetic risk group (Table IIIA); however, high FLT3 expression was significantly associated with inferior EFS (P=0.026) and OS (P=0.018) (Table IIIB); Fig. 1D-F).

![High FLT3 expression in FLT3 ITD positive AML patients did not predict survival (A-C). In FLT3 ITD negative AML patients high FLT3 surface expression was significantly associated with inferior EFS [17.39 ± 7.90 (5.44 - 34.95) vs 37.50 ± 11.52 (16.32 - 58.82) (P=0.026)] (D) and inferior overall survival (OS) [25.51±10.07 (9.01-46.04) vs 42.70±13.77 (16.72-66.71) (P=0.018)] (F), but had no effect on disease free survival (DFS) (E). Median values of FLT3 surface expression (percentage) were used as cut off point for categorization into high or low expression.](/content/175/2016/143/Suppl 1/img/IJMR-143-11-g002.png)

- High FLT3 expression in FLT3 ITD positive AML patients did not predict survival (A-C). In FLT3 ITD negative AML patients high FLT3 surface expression was significantly associated with inferior EFS [17.39 ± 7.90 (5.44 - 34.95) vs 37.50 ± 11.52 (16.32 - 58.82) (P=0.026)] (D) and inferior overall survival (OS) [25.51±10.07 (9.01-46.04) vs 42.70±13.77 (16.72-66.71) (P=0.018)] (F), but had no effect on disease free survival (DFS) (E). Median values of FLT3 surface expression (percentage) were used as cut off point for categorization into high or low expression.

It was observed that patients who were negative for FLT3 ITD and had low FLT3 expression had a trend towards improved OS (p=0.058) when compared with FLT3 ITD negative and high FLT3 expression and those with patients who were positive for FLT3 ITD (Fig. 2A-C).

![Survival of patients with FLT3 ITD positive vs FLT3 ITD negative and high FLT3 expression vs FLT3 ITD negative and low FLT3 expression: [event free survival, EFS (P=0.088) (A), disease free survival, DFS (P=0.464) (B), and overall survival, OS (P=0.058) (C)]. Median values of FLT3 surface expression (percentage) were used as cut-off point for categorization into high or low expression.](/content/175/2016/143/Suppl 1/img/IJMR-143-11-g006.png)

- Survival of patients with FLT3 ITD positive vs FLT3 ITD negative and high FLT3 expression vs FLT3 ITD negative and low FLT3 expression: [event free survival, EFS (P=0.088) (A), disease free survival, DFS (P=0.464) (B), and overall survival, OS (P=0.058) (C)]. Median values of FLT3 surface expression (percentage) were used as cut-off point for categorization into high or low expression.

Discussion

In AML, incidence of FLT3 ITD has been reported to vary from 15-35 per cent in western countries1011, whereas the studies from India analyzing AML patients showed 7-25 per cent incidence of FLT3-ITD mutation56 as compared to 16 per cent positivity in the current study. Although we could not identify any baseline characteristic associated with FLT3 ITD, it is noteworthy that those with FLT3 ITD had a white blood cell count which was three times that of patients who were negative for FLT3 ITD. We have previously shown that high WBC count at presentation is independently associated with poor outcome in AML4.

FLT3 ITD mutation is involved in autophosphorylation of tyrosine domain, which results in enhanced proliferation of myeloblasts. In the present study FLT3-ITD mutation were evaluated along with FLT3 transcript and surface expression in AML along with outcome. FLT3 expression was similar whether patient was FLT3 ITD positive or negative. Impact of FLT3 ITD surface expression on survival was observed only in FLT3 ITD negative patients. Clinical trials using RTK inhibitors showed promising results in AML by downregulating expression of FLT312131415.

We could not demonstrate a difference in survival with respect to the presence or absence of FLT3 ITD. Our study was limited by the fact that sample size was small, and associated mutations in FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain and nucleophosmin which could have altered the differences in survival, were not evaluated as part of this study.

In conclusion, our study evaluated FLT3 expression and FLT3 ITD mutation in adult AML patients. High FLT3 expression was associated with inferior survival outcome in FLT3 ITD negative patients.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Implications of FLT3 mutations in the therapy of acute myeloid leukaemia. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2007;2:135-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biologic and clinical significance of the FLT3 transcript level in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:1901-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2010;115:453-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased coexpression of c-KIT and FLT3 receptors on myeloblasts: independent predictor of poor outcome in pediatric acute myeloid leukaemia. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2013;84:390-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of FLT3 ITD and FLT3-Asp835 mutations in de novo acute myeloid leukemia: evaluation of incidence, distribution pattern, correlation with cytogenetics and characterization of internal tandem duplication from Indian population. Cancer Invest. 2010;28:63-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- FLT3 and NPM1 mutations in a cohort of AML patients and detection of a novel mutation in tyrosine kinase domain of FLT3 gene from Western India. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1703-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haematological & molecular profile of acute myelogenous leukaemia in India. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:256-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- FLT3 and NPM-1 mutations in a cohort of acute promyelocytic leukaemia patients from India. Indian J Hum Genet. 2014;20:160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children's Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92:2322-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic significance of FLT3 mutations in pediatric non-promyelocytic acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2005;29:617-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and prognostic significance of Flt3 internal tandem duplication in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:89-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sorafenib: targeting multiple tyrosine kinases in cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2014;201:145-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of quizartinib in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2013;22:1659-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: clinical implications and limitations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:243-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sorafenib plus all-trans retinoic acid for AML patients with FLT3-ITD and NPM1 mutations. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93:533-6.

- [Google Scholar]