Translate this page into:

Genotyping & diagnostic methods for hepatitis C virus: A need of low-resource countries

For correspondence: Dr Anoop Kumar, Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory, National Institute of Biologicals, A-32, Sector-62, Noida 201 309, Uttar Pradesh, India e-mail: akmeena87@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a blood borne and transfusion-transmitted infection (TTI). It has emerged as one of the major health challenges worldwide. In India, around 12-18 million peoples are infected with HCV, but in terms of prevalence percentage, its looks moderate due to large population. The burden of the HCV infection increases due to lack of foolproof screening of blood and blood products before transfusion. The qualified screening and quantification of HCV play an important role in diagnosis and treatment of HCV-related diseases. If identified early, HCV infection can be managed and treated by recently available antiviral therapies with fewer side effects. However, its identification at chronic phase makes its treatment very challenging and sometimes ineffective. The drugs therapy for HCV infection treatment is also dependent on its genotype. Different genotypes of HCV differ from each other at genomic level. The RNA viruses (such as HCV) are evolving perpetually due to interaction and integration among people from different regions and countries which lead to varying therapeutic response in HCV-infected patients in different geographical regions. Therefore, proper diagnosis for infecting virus and then exact determination of genotype become important for targeted treatment. This review summarizes the general information on HCV, and methods used for its diagnosis and genotyping.

Keywords

Hepatitis

hepatitis C virus

hepatitis C virus genotypes

molecular diagnostic

nucleic acid testing

serological assay

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has emerged as one of the major health challenges with an estimated 200 million HCV-infected people covering about 3.3 per cent of the world population and is responsible for around 350,000 deaths per year12. HCV infection is a blood borne infection, which mainly causes liver fibrosis which advances into liver cirrhosis and liver cancer3. Low-resource regions such as India, East Asia, North Africa and the Middle East contribute to 80 per cent of the global burden of HCV infection4. Around nine per cent population of world's HCV-infected individuals is living in India and accounts for major share of HCV infected people (~12-18 million), the overall prevalence of HCV is considered low to moderate (1-1.5%) due to higher population size56. HCV is mainly transmitted through transfusion of infected blood and blood products. After transmission, the virus may remain in latent phase due to suppression by host immune system. However, during its infectious phase, the replication of HCV is very robust, and around 10 trillion virion particles can be produced per day7. HCV is an RNA virus and its genetic diversity is constantly evolving due to rapid globalization, which ultimately results in varying therapeutic response in different geographical regions. On the basis of genomic variability, HCV is classified into seven major genotypes and 67 subtypes8. In India, HCV is responsible for acute viral hepatitis in up to 21 per cent910 and chronic liver disease in 14-26 per cent cases of HCV infections1011. Epidemiological studies have shown that the persistence of HCV infection is a major risk for development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)12. HCC is the fifth most common cancer and a major cause of death in patients with chronic HCV infection and responsible for approximately one million deaths each year1314. Earlier, the available antiviral therapies were effective in the treatment of HCV infection only at early stages and its identification and treatment at chronic stage were generally meaningless. But now, with the advancement in medical research, newer anti-HCV drugs have been developed which are also useful in the advanced cirrhosis caused by HCV1516.

HCV can be detected by serological tests employing anti-HCV antibodies and molecular tests using molecular probes complementary to HCV RNA sequence17. As per Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and 1945 and rules thereunder, the screening of blood units with third-generation serological assays is mandatory in India18. Fourth-generation serological assays with higher sensitivities are available which claim to reduce the window period. The molecular assays not only help in the early diagnosis but also confirm the infection stage. The diagnosis and quantification of HCV with highly sensitive and specific method play a crucial role in the management of HCV infection. It has been reported that different genotypes of HCV respond differently to anti-HCV therapy19. These genotypes differ from each other at their genomic levels. HCV is prone to transcriptional variations during the process of replication of its genome. In addition, the genome of HCV is constantly evolving due to globalization. This review summarizes information on HCV molecular diagnostic methods and their applications used in various parts of the world.

HCV genome organization and function

HCV is a member of family Flaviviridae and has about 9.6 kb positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome. The HCV genome contains single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by highly structured untranslated regions (UTRs) which are essential for RNA replication (Fig. 1)20. This single ORF codes for three structural and six non-structural proteins. The structural proteins are core protein (C) and two envelope proteins E1 and E2. Non-structural proteins are named as NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B. Two proteins p7 and F are also encoded due to frame shifting in the coding region. Core protein of HCV is an RNA binding basic protein, which forms viral capsid. It is released as a 191 amino acid (aa) precursor of around 23-kDa molecular weight containing three conserved domains (122 aa N terminal hydrophilic domain, 50 aa hydrophobic C terminal domain and 20 aa signal peptide domain)21. Besides viral capsid formation, it also interacts with various cellular proteins and pathways that play an important role in HCV life cycle22. E1, E2 and type-1 transmembrane proteins are crucial components of viral envelope and are also essential for the viral entry and fusion with host cell2324. During early phases of viral infection, E2 plays a vital role by initiating interaction with one or several components of the receptor complex2526. Function of E1 is not clearly understood, but it is hypothesized to be involved in the intracytoplasmic viral-membrane fusion2526.

![Schematic representation of genome organization of hepatitis C virus. The entire genome encodes a polyprotein, which is further processed into three structural [core (C), envelop protein (E1 & E2)] and five non-structural proteins [NS1, NS2, NS3, NS4 & NS5]; Protein positions are shown by numbers on the upper part of the scheme. Figure modified and reproduced with permission from Ref 20.](/content/175/2018/147/5/img/IJMR-147-445-g001.png)

- Schematic representation of genome organization of hepatitis C virus. The entire genome encodes a polyprotein, which is further processed into three structural [core (C), envelop protein (E1 & E2)] and five non-structural proteins [NS1, NS2, NS3, NS4 & NS5]; Protein positions are shown by numbers on the upper part of the scheme. Figure modified and reproduced with permission from Ref 20.

Non-structural protein, NS2 is a 21-23 kDa transmembrane protein that contains two internal sequences, which are responsible for ER membrane association27. NS2 is a short-lived protein and acts as a zinc-dependent metalloprotease with NS3 amino-terminal domain202829. NS3 is a multifunctional protein having serine protease domain and a helicase/NTPase domain in its N and C terminal, respectively. The 21-30 aa central region of NS4A acts as a cofactor for protease activity of NS3. This complementary interaction of NS3-NS4A is attractive target for the anti-HCV therapy. The anti-HCV therapies are designed to disrupt this interaction to break infectious pathway1930. NS4B is a 261 aa membrane protein having four transmembrane domains and helps in membrane association for replication complex3132, inhibits cellular synthesis3334 and modulates RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) activity of NS5B35. NS5A, a 56-58 kDa phosphorylated zinc-metalloprotein, plays an important role in virus replication and regulation of cellular pathways. NS5A provides the resistance against interferon by binding to interferon-α, protein kinase R (PKR) and inhibits its antiviral effect36. NS5B, an RdRp, is a tail-anchored protein3738 and forms classical ‘fingers, palm and thumb’ structure. The interaction between the fingers and thumb subdomains is essential for the complete catalytic cycle to permit synthesis of positive and negative RNA strand of HCV39. The p7, a 63 aa small polypeptide, contains two transmembrane α-helix domains connected by a cytoplasmic loop. A mutation or deletion in its cytoplasmic loop suppresses HCV infectivity in intraliver transfections40.

Natural history of hepatitis C virus

The understanding of the viral persistence and modes of transmission is important for the prevention of HCV infection. HCV is generally transmitted through transfusion of infected blood, unprotected high-risk sexual activity, organ transplantation from infected donor and mother to foetus. With the implementation of improved screening methods, reduction in HCV transmission from 0.0002 to 0.00005 per cent has been observed in developed countries414243.

The better understanding of the viral natural history plays an important role in the viral management and disease outcome. In a population, infected with HCV, it has been observed that in 15-45 per cent individuals, the infection gets spontaneously cleared within six months while in 55-85 per cent of the individuals, it persists. In acute phase, 70-80 per cent of the HCV-infected individuals are asymptomatic and unaware about the infection till it reaches the chronic phase. Of the infected individuals, 75-85 per cent may develop chronic infection which advances into liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, extrahepatic complications and HCC44. The characteristics of persistence of HCV infection and development of the chronic infection may differ from individual to individual depending on factors such as age, immune response, degree of inflammation, HIV/HBV coinfection or lifestyle habit such as consumption of alcohol44. According to a study performed by Kiyosawa et al45, the average time taken for the development of chronic hepatitis was about 10 yr, development of cirrhosis was 21 yr and development of HCC was around 29 years. With an estimate around 10-15 per cent of HCV-infected cases will progress into liver cirrhosis within first 20 yr, which increases the risk of developing HCC44.

HCV genotypes, subtypes and anti-HCV therapy

As mentioned previously, HCV strains are classified into seven genotypes based on the phylogenetic and sequence analyses of HCV genomes, and within each genotype, HCV is further classified into 67 subtypes46. In India, genotype 3 is the predominant genotype (~63.85%) followed by genotype 1 (25.72%). HCV genotype 3 is more prevalent in the northern, eastern and western parts of India and genotype 1 is more prevalent in the southern India47. Despite, the widespread prevalence of genotypes 3 and 1, there also exists increased prevalence of genotypes 4 and 6 in certain regions of the country. Genotype 4 is found mostly in south Indian patients from the States of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Genotype 6 is found to be prevalent in patients belonging to northeastern parts of India48. An increased prevalence of genotype 6 in various parts of the neighbouring country of Myanmar which shares its boundaries with the northeastern States of India, has also been observed49. Genotype 2 is rarely reported while genotype 5 is yet to be reported from India47.

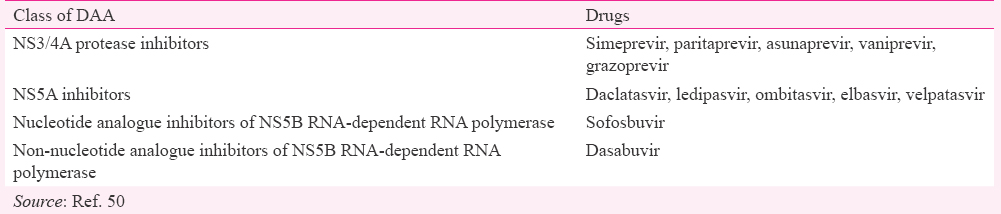

With the advancement in medical research and clinical trials of new drugs, the treatment of HCV infection has been shifted from pegylated interferon/ribavirin to direct-acting antiviral (DAA) combination therapies. These DAAs target and inhibit key stages of the HCV replication pathway. DDAs are classified into four classes on the basis of their mechanism of action and target50 (Table).

The combined drugs therapy may involve the use of two to three drugs515253. In 2011, DAAs, telaprevir and boceprevir were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for anti-HCV therapy54. These first-generation DAAs inhibit NS3/4A protease during their action against HCV. However, both were withdrawn from US market after three years in 2014. HCV infection treatment with protease inhibitors (PIs) has shown better results with significant side effects55. However, during clinical trials, second-generation PIs have shown better results with the fewer side effects in comparison to first-generation DAAs. In 2016, two new combinations of DAAs, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and grazoprevir/elbasvir were approved licensed in Europe and USA56. At present, three regimens are recommended for the treatment of patients infected with HCV genotype 1. These regimens are simeprevir plus sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir with or without ribavirin57. Ghany et al58 reported 35-70 per cent increased response with the use of triple combination therapy in comparison to double combination therapy for treatment of HCV genotype 1. In case of genotypes 2 and 3, regimen of sofosbuvir and ribavirin is recommended. For HCV genotypes 4, 5 and 6 and HIV co-infection, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir with or without ribavirin have been recommended by both the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America575960. Both of these regimens have also been approved by US-FDA for HCV-infected patients coinfected with HIV.

HCV genotyping methods

The genotype of HCV for diagnosis is mostly determined by sequencing of genomic nucleotide sequence or by kit-based assays which employ complementary probes to report genotype present in a specimen. Sequencing of highly conserved regions such as NS5, core, E1 and 5’UTR is the most commended method used for genotyping of HCV61. The kit-based assays are easy-to-use and do not require expertize as is required for sequencing. Both TruGene 5’NC HCV Genotyping kit (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Division, Tarrytown, NY) and Versant™ HCV Genotype Assay LiPA (version I, Siemens Medical Solutions, Diagnostics Division, Fernwald, Germany) are based on 5’UTR sequence. Both these kits use reverse hybridization with genotype-specific oligonucleotide probes62. Both kits claim to detect HCV genotypes 1 to 6. Abbott RealTime HCV Genotype II Kit claims to detect genotype 1 to 5. HCV genotype kit cobas® HCV GT, manufactured by Roche claims to identify HCV genotypes 1-6 and can discriminate between subtype a and b of genotype-1. Fully automated system cobas® 4800 (Roche, USA) has also been launched for HCV genotyping. The complementary probes against three regions, 5’UTR, Core and NS5B of HCV genome have been incorporated for genotyping and subtyping accuracy.

Duarte et al63 developed xMAP Luminex assay system, a liquid microarray-based HCV genotyping method. The complementary sequences against most variable region NS5B and highly conserved 5’UTR were used to determine HCV genotypes. The results shown were in 100 per cent concordance with Versant™ HCV Genotype Assay LiPA. Two high-throughput methods like LightCycler® systems based on metlting curve analysis6465 and using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) technology have also been developed66. Athar et al67 developed a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay using two dual-labelled self-quenched probes of core region of HCV genome. They used the specific probes of the HCV core region and exact HCV genotypes could be determined by melting curves from the respective probes in RT PCR67.

Other alternative HCV genotyping methods are amplification with type-specific primers or type-specific probes6869, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis70, line-probe testing71, and heteroduplex mobility analysis7273.

Diagnostic methods for HCV

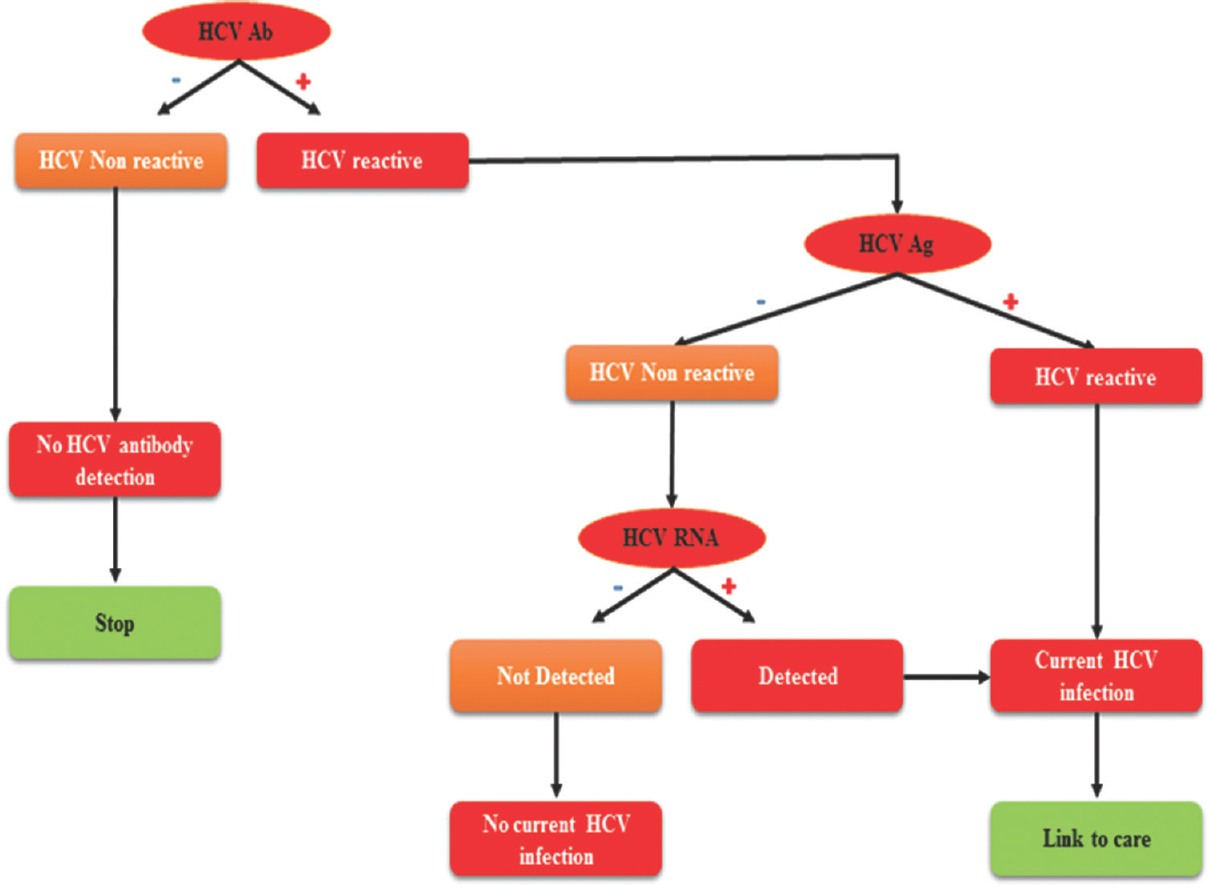

HCV infection can be detected using serological methods and molecular methods (Fig. 2)74. Accurate diagnosis of HCV infection is important before initiating therapy. The diagnosis to know the stage of HCV infection is also crucial because HCV infection gets cleared within 6-12 months in 15-45 per cent of infected individuals and these individuals remain anti-HCV antibody positive without any detectable viraemia. In such cases, physicians must differentiate between the infected and recovered individuals75. Earlier, the serological reactivity of HCV infection by ELISA has been confirmed by recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA). RIBA has been discontinued as a confirmatory method for HCV infection diagnosis. Nowadays, nucleic acid testing (NAT) is considered as the gold standard to confirm active HCV infection76. NAT is based on the detection of HCV RNA or HCV genome in a specimen.

- Algorithm for hepatitis C virus testing. Detection of HCV antibody (Ab) is done by laboratory assay. Further testing of HCV Ab positive samples will show either current or past HCV infection or false HCV antibody positivity. Positive samples should be tested by nucleic acid-based testing (NAT), as positive indicates current HCV infection and negative indicates either past or resolved HCV infection, or false Ab positivity. Modified and reproduced from Ref 71.

Serological assays for HCV diagnosis

HCV can be diagnosed by the detection of the anti-HCV antibody in the serum or plasma samples, where a non-reactive result is considered as absence of HCV infection. Further, to declare an HCV infection as active infection, it needs to be confirmed by HCV RNA test. Assays used for the detection of the HCV infection have been evolved to minimize the number of false positives with improvement in their specificity. Successive generations of the HCV serological assays have not only improved sensitivity and specificity but have also reduced the window period for the detection of infection777879.

-

First-generation assay: These were based on binding of anti-HCV antibody and recombinant protein-containing NS4 (C100-3) epitopic region. These assays could identify about 80 per cent anti-HCV IgG in post-transfusion cases; therefore, their sensitivity and specificity were very low80. Their false positivity rate in low-risk populations has been reported to be as high as 60 per cent.

-

Second-generation assays: The recombinant proteins from core (structural), NS3 and NS4 were used as binding proteins with anti-HCV antibody. These assays have been reported to have better sensitivity and specificity. Second-generation assays reduced window period of HCV to 10-24 wk79.

-

Third-generation assays: The immunosorbent contains recombinant proteins of core, NS3, NS4 and NS5 regions. The diagnosis specificity of more than 99 per cent has been reported for this category of assays81. Third-generation assays can show false-negative results in the patients who are immunocompromised or undergoing haemodialysis62. In India, as per Drugs and Cosmetics act, 1940 and 1945, the use of third-generation serological assays is mandatory for screening of blood donor units for HCV infection before transfusion67.

-

Fourth-generation assays: Fourth-generation assays are also known as ‘antigen-antibody combo’ tests because the principle of these assays is based on the detection of both anti-HCV antibody and HCV antigen at the same time. These assays are highly sensitive and are responsible for high reduction in window period. The average window period is 26.8 days for these assays79.

Earlier, according to CDC, the person having positive serological test had to be confirmed by RIBA for HCV infection, but now HCV RNA nucleic acid testing is used to confirm active HCV infection76.

Recombinant immunoblot assays (RIBA)

RIBA has previously been used for confirmation of the HCV infection and it was based on the detection of anti-HCV antibody by immobilized HCV antigen and synthetic peptide from structural (core) and non-structural (NS3 and NS5) proteins as individual bands onto a membrane. The appearance of at least two bands was considered as indicator for confirmed infection and appearance of single band was considered as indeterminate result. Indeterminate cases were due to non-specific cross-reacting antibodies or the broad humoral response had not be triggered by the recent infection. In general, the results of one-week old HCV-infected individuals were reported as indeterminate who might be converted into confirmed cases after 1-6 months of infection82.

Rapid assays

Rapid tests are configured to generate results within half an hour and can be used for point-of-care testing. These assays do not require sophisticated instrument and highly trained staff. Three rapid tests (Orasure, Chembio and Medmira) for anti-HCV IgG have been evaluated by the CDC in laboratory as well as in field settings. The specificities and sensitivities of these tests were >99 per cent and 86-99 per cent, respectively83. The main disadvantage in serological assays is their inability to discriminate between active and non-active infection. Serological assays test positive due to the presence of anti-HCV IgG even after the clearance of viraemic particles by immune system. The other drawback of these assays is large window period. During this period, HCV RNA is the first detectable diagnostic marker and is followed by core antigen diagnostic marker. The generation of anti-HCV antibody is followed by these two diagnostic markers. Due to this drawback, blood bank in the USA adopted nucleic acid-based testing (NAT) as a gold standard method for HCV diagnosis in late 1990s84 and due to implementation of NAT, the transfusion-related risk of HCV infection has been reduced to 0.0001 per cent in USA6.

Nucleic acid testing (NAT)

NAT is a molecular technique and is based on amplification and detection of viral nucleic acid. NAT reduces the risk of transfusion transmitted infections (TTIs); therefore, it adds an additional layer of safety to the blood to be used for transfusion. Two types of technologies, PCR and transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) are routinely used for NAT testing of blood donations for HCV infection. The main advantage of the nucleic acid testing is the early detection of HCV infection. HCV RNA in infected samples can be detected within one week of initial exposure19. Due to high sensitivity and specificity, NAT is used for the resolution of samples which are reported as indeterminate and or false negative by serological methods85.

In an international survey on NAT testing of about 300 million blood donations for HIV and HCV and about 100 million donations for HBV infection in 37 countries, Roth et al86 reported 3000 NAT yield. These blood donations were reported as non-reactive by serological screening methods86.

NAT blood screening experience in low-resource countries

Realizing the need and benefits of NAT testing, low-resource countries are also implementing NAT testing on national or centre level for screening blood donation. In 2007, at Thai blood centre, 486,676 seronegative blood donations were screened by NAT. The NAT yield rates for HIV-1, HCV and HBV were 1:97,000, 1:490,000 and 1:2800, respectively87. In north India at a blood bank, 73,898 blood donations were screened for HIV, HBV and HCV by ELISA and individual donor-nucleic acid amplification test (ID-NAT). Out of all donations, 1104 (1.49%) donations were found positive by multiplex NAT. Furthermore, 37 HCV, 73 HBV, one HIV and 10 HBV-HCV co-infected cases were reported by NAT testing who were non-reactive by ELISA testing88. In India, different groups at different centres reported different NAT yield rates for HCV infection. The NAT yield reported by Agarwal et al88 was 1 in 610. Kumar et al89 reported 1 in 753 and Mangwana and Bedi90 as 1 in 974. In Brazil till July 2005, 139,678 donations were screened in pools of 6 to 12 donations by in-house RT-PCR method having sensitivity of 500 IU/ml for all six genotypes of HCV. Out of 139,678 donations, 315 (0.23%) were found to be positive for HCV RNA91.

The NAT testing can be performed for individual donations (ID-NAT) or min-pools (MP-NAT). A mini-pool may be prepared by pooling 6, 8, 16 or 24 individual donations. Although NAT is very beneficial due to the requirement of higher investment for its implementation, low-resources countries like India are not able to make it mandatory for screening of blood for TTIs. To make blood screening cost-effective, different counties and institutions are using mini-pools of 6, 8, 16 and 24. In Germany, after introduction of MP-NAT in 1997, 23 HCV, 2 HIV-1 and 43 HBV-infected blood donation were detected in around 31 million blood donations92. Based on the data analysis of NAT, Mathur et al93 have shown that NAT can be made cost-effective by pooling method (mini-pools) in India. There are some disadvantages of mini-pools in NAT testing; first, dilution of the viral copy number decreases sensitivity. Second, if a pool is found reactive, all pooled donations need to be tested for the identification of the individual positive donation. Therefore, to overcome these limitations, ID-NAT testing has been suggested.

Testing of HCV infection by NAT for its RNA detection is done by PCR or TMA or branched deoxyribonucleic acid (bDNA) signal amplification. In NAT testing technology of HCV, highly conserved 5’ UTR of HCV genome is used as a target sequence for its detection94. This region is conserved among all genotypes of HCV; therefore, primers are designed to hybridize with the least possible discrepancies among six different HCV genomes. Most of the manufacturers of NAT testing kits have developed their assays compatible only to their equipment. All types of platforms, manual, semi-automated and fully automated are available for HCV NAT testing. In research laboratories, qualitative HCV-NAT is used for diagnosis using conventional RT-PCR, but diagnostics laboratories have started using kits for diagnosis of HCV.

The qualitative NAT has been used for screening of HCV infection during blood donation and to confirm viraemia in patients95. The lower limit of detection of ≤50 IU/ml is claimed by various manufacturers for their qualitative molecular methods. On the other hand, viral load determination of HCV disease prognosis can be accomplished by quantitative RT-PCR and bDNA technology.

The prevalence of HCV in India has been higher in comparison to Western Europe and USA96. The HCV prevalence reported by various groups in Indian population is 1 in 413890, 1 in 199788 and 1 in 253689.

Although NAT reduces the risk of TTIs such as HCV in the Indian context, there are some limitations for its mandatory implementation. In India, the use of NAT in regular practises has been restricted due to high cost, technical demand such as trained workforce or equipment consumables97. In 2014, Chandrashekar98 developed an in-house assay for safety of blood at a minimal cost. This assay was found feasible to implement in a small molecular biology unit in any types of blood banks98.

The introduction of the NAT to detect window period donations in 300,000 to 3,000,000 blood donations, could save around three lives in the developed countries, whereas in developing countries like India it may be 300 to 3000 times more beneficial as compared to developed countries90.

Conclusion

The nucleic acid-based testing for HCV has reduced its window period to around one week. This technique has proved its advancement and needs over conventional serological methods99. Therefore, the implementation of NAT will be of great benefit to low-resource countries due to high prevalence of HCV.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57:1333-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular assay and genotyping of hepatitis C virus among infected Egyptian and Saudi Arabian patients. Virology (Auckl). 2015;6:1-0.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transfusion transmission of HCV, a long but successful road map to safety. Antivir Ther. 2012;17:1423-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: Updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology. 2014;59:318-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies in Western India. Indian J Med Res. 1995;101:91-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus in patients with acute and chronic liver disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1992;11:146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-73e1.

- [Google Scholar]

- EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Prevalence around the world, factors interacting, and role of genotypes. Epidemiol Rev. 1999;21:180-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical use of hepatitis C virus tests for diagnosis and monitoring during therapy. Clin Liver Dis. 1999;3:717-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory assays for diagnosis and management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4407-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules, 1945, as amended up to 30th June 2005. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/Drugs&CosmeticAct.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- New therapeutic strategies in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:1009-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus genetic variability and evolution. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:831-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression and identification of hepatitis C virus polyprotein cleavage products. J Virol. 1993;67:1385-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Properties of the hepatitis C virus core protein: A structural protein that modulates cellular processes. J Viral Hepat 2000:2-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the genome and structural proteins of hepatitis C virus resolved from infected human liver. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1497-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of the hepatitis C virus glycoproteins in infection. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10:101-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- A quantitative test to estimate neutralizing antibodies to the hepatitis C virus: Cytofluorimetric assessment of envelope glycoprotein 2 binding to target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1759-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Membrane topology of the hepatitis C virus NS2 protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33228-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the hepatitis C virus-encoded serine proteinase: Determination of proteinase-dependent polyprotein cleavage sites. J Virol. 1993;67:2832-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proteolytic processing and membrane association of putative nonstructural proteins of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10773-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complex formation between the NS3 serine-type proteinase of the hepatitis C virus and NS4A and its importance for polyprotein maturation. J Virol. 1995;69:7519-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- An N-terminal amphipathic helix in hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS4B mediates membrane association, correct localization of replication complex proteins, and HCV RNA replication. J Virol. 2004;78:11393-400.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mobility of the hepatitis C virus NS4B protein on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and membrane-associated foci. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:1415-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of protein synthesis by the nonstructural proteins NS4A and NS4B of hepatitis C virus. Virus Res. 2002;90:119-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus NS4A and NS4B proteins suppress translation in vivo . J Med Virol. 2002;66:187-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity by the non-structural (NS) 3 helicase and the NS4B membrane protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45670-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanisms of interferon resistance mediated by viral-directed inhibition of PKR, the interferon-induced protein kinase. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;78:29-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- The hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase membrane insertion sequence is a transmembrane segment. J Virol. 2002;76:13088-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants for membrane association of the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44052-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from hepatitis C virus reveals a fully encircled active site. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:937-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- The p7 polypeptide of hepatitis C virus is critical for infectivity and contains functionally important genotype-specific sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11646-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C: The end of the beginning and possibly the beginning of the end. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:317-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current prevalence and incidence of infectious disease markers and estimated window-period risk in the American Red Cross blood donor population. Transfusion. 2002;42:975-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yield of HCV and HIV-1 NAT after screening of 3.6 million blood donations in central Europe. Transfusion. 2002;42:862-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006;3:47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transition of antibody to hepatitis C virus from chronic hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81:1089-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global distribution and prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2015;61:77-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotypes of hepatitis C virus in the Indian sub-continent: A decade-long experience from a tertiary care hospital in South India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:349-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotypic distribution of hepatitis C virus in Thailand and Southeast Asia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126764.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advances in hepatitis C therapy: What is the current state - What come's next? World J Hepatol. 2016;8:139-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent trends in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:22-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direct acting anti-hepatitis C virus drugs: clinical pharmacology and future direction. J Transl Int Med. 2017;5:8-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Approval of Incivek (telaprevir) a Direct Acting Antiviral drug (DAA) to Treat Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Available from: http://www.natap.org/2011/HCV/telap_02.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus resistance to direct-acting antiviral drugs in interferon-free regimens. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:70-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Recommendations for Testing Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org

- [Google Scholar]

- An update on treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 2011 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2011;54:1433-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virologic response following combined ledipasvir and sofosbuvir administration in patients with HCV genotype 1 and HIV co-infection. JAMA. 2015;313:1232-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness of simeprevir plus sofosbuvir, with or without ribavirin, in real-world patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:419-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- The “gold-standard,” accuracy, and the current concepts: Hepatitis C virus genotype and viremia. Hepatology. 1996;24:1312-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: An update. Hepatology. 2009;49:1335-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel hepatitis C virus genotyping method based on liquid microarray. PLoS One. 2010;5 pii: e12822

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotyping of hepatitis C virus by melting curve analysis: Analytical characteristics and performance. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2405-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotyping of hepatitis C virus types 1, 2, 3, and 4 by a one-step LightCycler method using three different pairs of hybridization probes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2046-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (mass spectrometry) for hepatitis C virus genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2810-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid detection of HCV genotyping 1a, 1b, 2a, 3a, 3b and 6a in a single reaction using two-melting temperature codes by a real-time PCR-based assay. J Virol Methods. 2015;222:85-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Typing hepatitis C virus by polymerase chain reaction with type-specific primers: Application to clinical surveys and tracing infectious sources. J Gen Virol. 1992;73(Pt 3):673-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus genotypes in France: Comparison of clinical features of patients infected with HCV type I and type II. J Hepatol. 1994;21:70-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of genotypes in the 5’ untranslated region of hepatitis C virus in Korea. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:643-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second-generation line probe assay for hepatitis C virus genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2259-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genotyping hepatitis C virus by heteroduplex mobility analysis using temperature gradient capillary electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4545-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simplified hepatitis C virus genotyping by heteroduplex mobility analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:477-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Testing for HCV infection: An update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:362-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spontaneous viral clearance following acute hepatitis C infection: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relevance of RIBA-3 supplementary test to HCV PCR positivity and genotypes for HCV confirmation of blood donors. J Med Virol. 1996;49:132-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved detection of anti-HCV in post-transfusion hepatitis by a third-generation ELISA. Vox Sang. 1995;68:15-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Declining value of alanine aminotransferase in screening of blood donors to prevent posttransfusion hepatitis B and C virus infection. The Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. Transfusion. 1995;35:903-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current testing strategies for hepatitis C virus infection in blood donors and the way forward. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2948-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of non-A, non-B hepatitis after screening blood donors for antibodies to hepatitis C virus and surrogate markers. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:596-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sensitivity and specificity of third-generation hepatitis C virus antibody detection assays: An analysis of the literature. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:87-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute hepatitis C: High rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:80-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of three rapid screening assays for detection of antibodies to hepatitis C virus. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:825-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- The declining risk of post-transfusion hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:369-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of serological transfusion-transmitted viral diseases and mutliplex nucleic acid testing in Malaysian blood donors. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013;49:647-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- International survey on NAT testing of blood donations: Expanding implementation and yield from 1999 to 2009. Vox Sang. 2012;102:82-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- One-year experience of nucleic acid technology testing for human immunodeficiency virus type 1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus in Thai blood donations. Transfusion. 2009;49:1126-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nucleic acid testing for blood banks: An experience from a tertiary care centre in New Delhi, India. Transfus Apher Sci. 2013;49:482-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Individual donor-nucleic acid testing for human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus and its role in blood safety. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2015;9:199-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Significance of nucleic acid testing in window period donations: Revisiting transfusion safety in high prevalence-low resource settings. J Pathol Nepal. 2016;6:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary screening of blood donors by nat testing for HCV-RNA: Development of an “in-house” method and results. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49:177-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experience of German Red Cross blood donor services with nucleic acid testing: Results of screening more than 30 million blood donations for human immunodeficiency virus-1, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus. Transfusion. 2008;48:1558-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on optimization of plasma pool size for viral infectious markers in Indian blood donors using nucleic acid amplification testing. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2012;6:50-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C virus variants and the role of genotyping. J Hepatol. 1995;23(Suppl 2):26-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular diagnostics of hepatitis C virus infection: A systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:724-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) screening of blood donors in India A Project Report, International Hospital Federation Reference Book, 2008/2009. Bernex: The International Hospital Federation (IHF); 2009. p. :66-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Half a decade of mini-pool nucleic acid testing: Cost-effective way for improving blood safety in India. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2014;8:35-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Refinement of a viral transmission risk model for blood donations in seroconversion window phase screened by nucleic acid testing in different pool sizes and repeat test algorithms. Transfusion. 2011;51:203-15.

- [Google Scholar]