Translate this page into:

Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in south coastal Karnataka, India, using spoligotyping

For correspondence: Dr Kiran Chawla, Department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College, MAHE, Manipal 576 104, Karnataka, India e-mail: kiran.chawla@manipal.edu

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Despite high occurrence of tuberculosis in India very little information is available about the genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates prevailing in coastal Karnataka, India. Thus, the present study was undertaken to explore the genetic biodiversity of M. tuberculosis isolates prevailing in south coastal region of Karnataka (Udupi District), India.

Methods:

A total of 111 Mycobacterial isolates were cultured in Lowenstein Jensen (LJ) medium and after obtaining growth, DNA was extracted and spoligotyping was performed. SITVIT WEB database was used to locate families of spoligotypes.

Results:

On analyzing the hybridization results of all 111 isolates on SITVIT WEB database 57 (51.35%) isolates were clustered into 11 Spoligotype International Types (SIT). The largest cluster of 14 (12.61%) isolates was SIT-48 (EAI1-SOM), followed by SIT-1942 (CAS1-Delhi) with 11 isolates (9.9%) and SIT-11 with seven (6.30%). Moreover, 23 isolates (20.72%) had unique spoligotypes and 31 (27.92%) were orphans. Spotclust analysis revealed that majority (67%) of orphan isolates were variants of CAS (37%) and EAI-5 (34%).

Interpretation & conclusions:

The present study revealed high biodiversity among the circulating isolates of M. tuberculosis in this region with the presence of mixed genotypes earlier reported from north and south India along with certain new genotypes with unique SITs. The study highlights the need for further longitudinal studies to explore the genetic diversity and to understand the transmission dynamics of prevailing isolates.

Keywords

Genetic diversity

genotyping

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

spoligotyping

In 2016, an estimated 10.4 million people developed tuberculosis and 1.67 million died from the disease globally, highlighting the devastation caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB). India reported the largest number of cases (25%) of the global total1. Comparing the share in global burden, the knowledge about the genetic diversity of strains prevailing in India is inadequate. Study on genetic diversity of MTB is important for effectively controlling the emerging drug-resistant strains. Further, it also enables us to understand the transmission dynamics and differentiate between reinfection and reactivation in patients with relapse. Application of molecular methods such as spoligotyping, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and Mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units-Variable number of tandem repeats (MIRU-VNTRs) is useful for understanding the prevailing MTB genotypes and their transmission within the population. Over the years, spacer oligonucleotide genotyping (spoligotyping) has emerged as the most widely used method for MTB genotyping after IS6110-based fingerprinting, which requires large quantities of good quality DNA and has a limitation in isolates having low copies of IS6110 elements2. Spoligotyping is based on DNA polymorphism in direct repeat (DR) locus of MTB. The latter contains multiple 36 base pair DRs which are well conserved and are interspersed with non-repetitive spacer sequences which are 34-41 base pairs long3. On comparing DR regions of several isolates of MTB, it was observed that the deletions and insertions in DRs occur, but the order of the spacers remains same. Thus, variation in the sequence of spacers is used to determine genetic diversity among isolates by targeting the DR locus for in vitro DNA amplification. Spoligotyping is a simple, rapid and sensitive test, and can be performed directly from the clinical samples even if the bacteria are not viable or are in tissues in paraffin-embedded blocks4.

The population of Udupi district in Karnataka State of India comprises a section of migratory people from other parts of Karnataka. It will be interesting to know about the circulating genotypes of MTB in this geographical area. Thus the present study was aimed to characterize the MTB isolates from pulmonary tuberculosis patients using spoligotyping and to identify the predominant MTB clades prevalent in Udupi district of south coastal Karnataka.

Material & Methods

A cross-sectional epidemiological study was carried out from January to August 2016 in the department of Microbiology, Kasturba Medical College (KMC), Manipal, Karnataka, in association with National JALMA Institute for Leprosy and other Mycobacterial Diseases (ICMR), Agra, after obtaining the approval of Institutional Research and Ethical Committee of KMC, Manipal.

Sample processing & DNA extraction:The stock isolates of MTB obtained from sputum of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients collected from designated microscopy centres of three taluks (Udupi, Kundapura and Karkala) in a stratified sampling technique from Udupi district from September 2011 to August 2014 in our previous study5, were used. For spoligotyping, the stock isolates were subcultured on Lowenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium (HiMedia, Mumbai) and incubated for four to eight weeks at 37°C. After obtaining the growth on LJ medium, DNA extraction was performed using a commercially available kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) as per manufacturer's instructions.

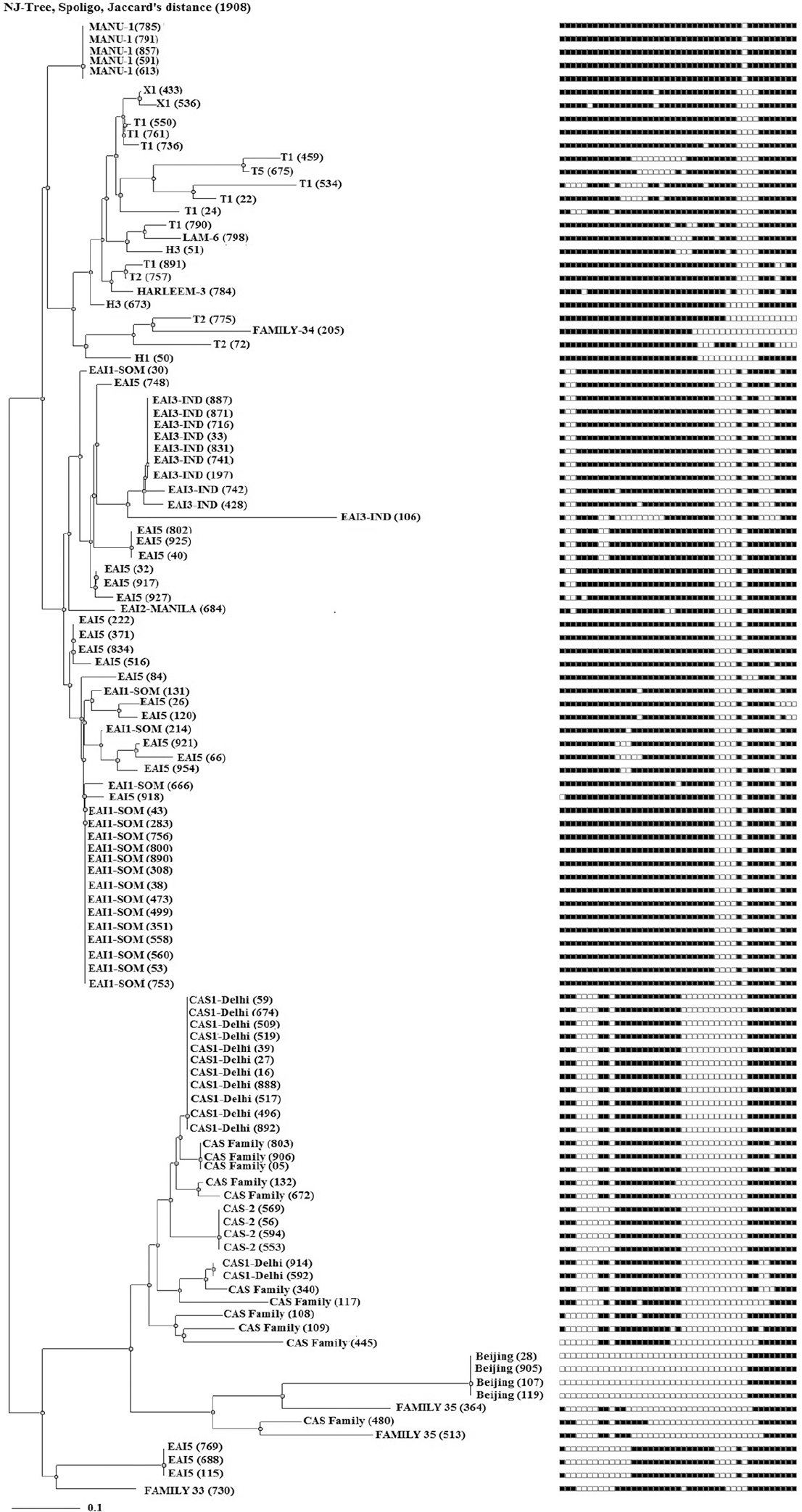

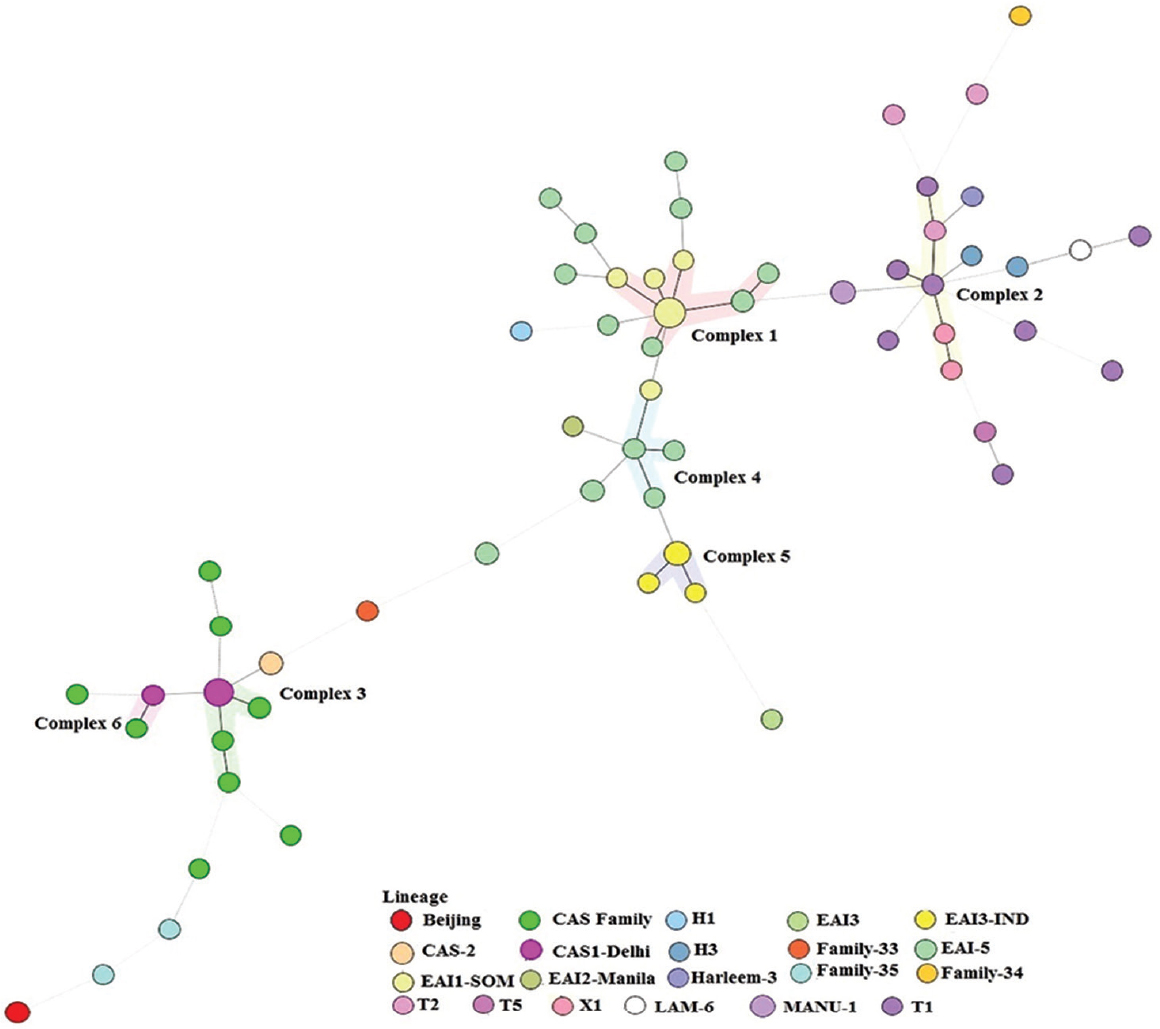

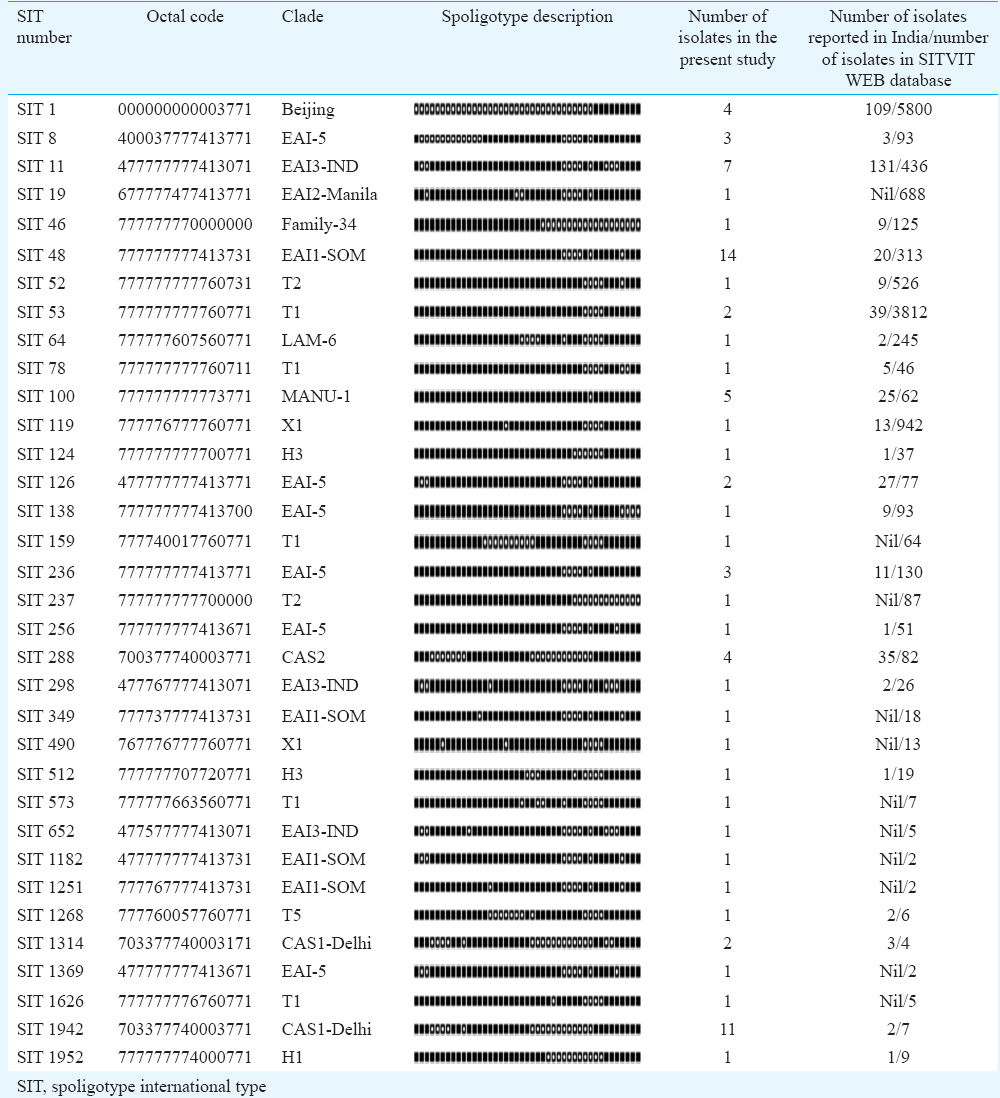

Spoligotyping: Spoligotyping was carried out by amplifying the whole DR region using the commercially available kit (Mapmygenome, Hyderabad) according to a standardized method using the designated primers’ pairs of DRa and DRb6. Master cycler gradient 5331 (Eppendorf, Germany) was used for DNA amplification. The amplified PCR products were hybridized with nitrocellulose membrane having covalently linked 43 spacer oligonucleotides following the manufacturer's instructions. MTB H37Rv and M. bovis were used as positive control and double-distilled water as a negative control. The hybridized fragments were identified using enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare, UK). The spoligotypes were initially reported as 43 digits binary representation of 43 spacers, one (1) was scored for positive hybridization and zero (0) for negative hybridization. The binary codes were converted into octal codes. The octal codes were analyzed using the SITVIT WEB (http://www.pasteur-guadeloupe.fr:8081/SITVIT_ONLINE) database to locate the families of spoligotypes7. A cluster was defined as two or more isolates with identical spoligotype patterns. However, if the spoligotype pattern in the SITVIT WEB database corresponded to only one isolate, then the pattern was called ‘unique’. The spoligotypes that did not match any pattern in the SITVIT WEB database were defined as ‘orphan’. The orphans were further analyzed by ‘Spotclust’, which assigns families based on SpolDB3.0 (http://tbinsight.cs.rpi.edu/run_spotclust.html)8. The evolutionary relationship of the clinical isolates was analysed based on spoligotyping data by calculating NJ tree dendrogram (Fig. 1) which was based on Jaccard Index and minimum spanning tree (Fig. 2) using MIRU-VNTR plus (http://www.miru-vntrplus.org/MIRU/index.faces)91011. Discriminatory power of spoligotyping was determined by calculating Hunter Gaston Discriminatory Index (HGDI)12. Association between demographic characteristics of the patients with the occurrence of clustered and non-clustered MTBisolates was examined using univariate odds ratio.

- A spoligotyping-based dendogram generated through N-J tree analysis using Mycobacterial Interspersed Repetitive Units-Variable Number of Tandem Repeats plus database showing genetic diversity of 111 clinical isolates from Udupi district, Karnataka, India.

- A minimum spanning tree based on phylogenetic lineages. The structure of the tree is represented by branches (continuous, dashed and dotted lines) and circles representing individual pattern. The length of the branches represents the distance between patterns while the complexity of the lines (continuous, grey dashed and grey dotted) denotes the number of allele/spacer changes between two patterns: solid lines, 1 or 2 or more changes (thicker ones indicate a single change, while the thinner one indicates 2 changes); grey dashed lines represent 3 changes; and grey dotted lines represent 4 or more changes. The size of the circle is proportional to the total number of isolates in our study, illustrating unique isolates (smaller nodes) versus clustered isolates (bigger nodes). The colour of the circles indicates the lineage to which the specific pattern belongs.

Results

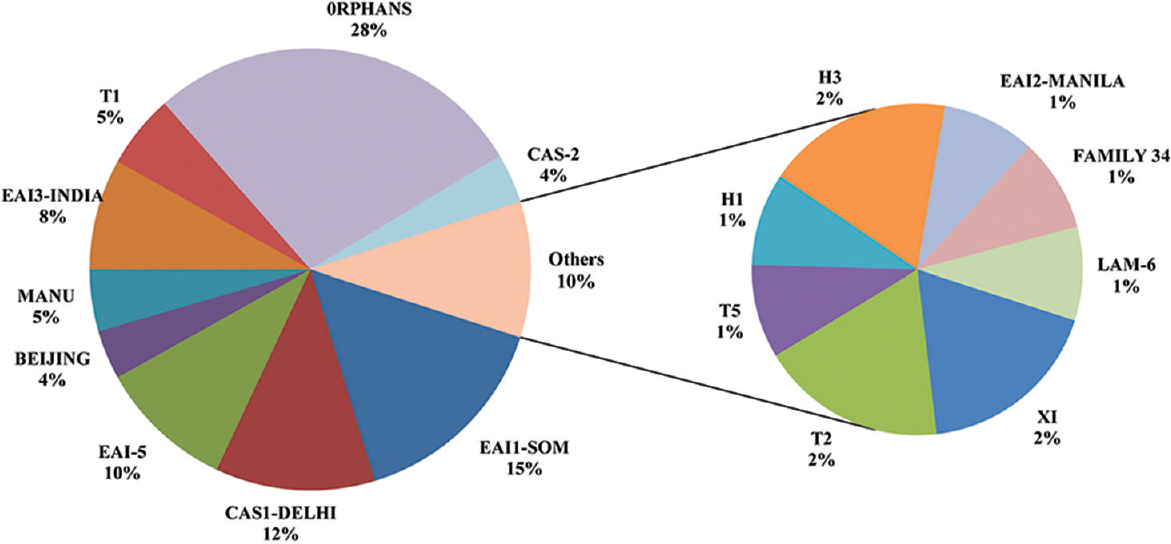

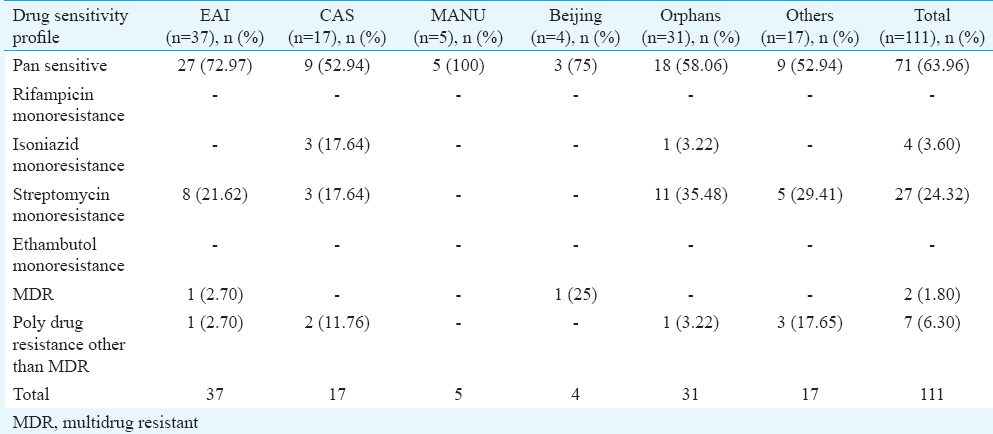

A total of 111 clinical isolates of MTB obtained from sputum samples of pulmonary tuberculosis patients were spoligotyped and analyzed. On SITVIT WEB analysis, a total of 57 (51.35%) isolates were clustered into 11 spoligotype international types (SITs) with SIT-48 (EAI1-SOM) being the largest cluster of 14 (12.61%) isolates, followed by SIT-1942 (CAS1-Delhi) and SIT-11 (EAI3-IND) with 11 (9.9 %) and seven (6.3%) isolates, respectively. Further 23 isolates (20.72%) had unique spoligotypes and 31 (27.92%) were orphans (Table I). The most prevalent clades prevailing in this region were EAI1-SOM (15.31%), CAS1-Delhi (12%) and EAI-5 (10%). Beijing (4%) and Harlem (3%) families, which are emerging worldwide and of major concern due to their association with drug resistance, were found less prevalent in this region (Fig. 3). MANU 4.5 per cent (5/111), X1 1.8 per cent (2/111), T2 1.8 per cent (2/111), T1 5.4 per cent (6/111), T5 0.9 per cent (1/111), H1 0.9 per cent (1/111), H3 1.8 per cent (2/111), EAI2-Manilla 0.9 per cent (1/111) and LAM-6 0.9 per cent (1/111) were the other clades reported in this study (Table I). We further analyzed 31 orphans isolates by Spotclust (SPOLDB3 based) to identify their most probable families. Spotclust analyses revealed that majority (67%) of orphans in this study were variants of clades CAS (37%) and EAI-5 (34%) with 11 and 10 clinical isolates, respectively. One clinical isolate each was found to be the variant of EAI1-SOM, EAI3, T2 and Family 33. Further two clinical isolates were found to be variants of Family 35, whereas three clinical isolates were found to be variants of T1. The distribution of clades in three taluks of Udupi district is shown in Fig. 4. Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients in relation to clustering of MTB isolates are shown in Table II. Two out (1.80%) of 111 patients had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) which shared SIT-48 (EAI-SOM) and SIT-1(Beijing) spoligotypes. Further, four (3.60%) isolates were monoresistant to isoniazid, 27 (24.32%) were monoresistant to streptomycin, seven (6.30%) were polydrug-resistant other than MDR and 71 (63.96%) were sensitive to all first-line drugs. The detailed description of drug resistance in isolates with respect to lineage is given in Table III. Thirteen (11.71%) patients were seropositive for HIV (mean age=41.54, SD=8.10, range: 30-57 yr), SIT-48 was shared by two isolates, one isolate each belonged to SIT-236, SIT-126, SIT-100, SIT-288, SIT-11, SIT-119, SIT-490, SIT-1268, SIT-52 and orphan. Discriminatory power of spoligotyping for 111 clinical isolates of Udupi district based on HGDI was found to be 0.93.

- A pie chart showing the distribution of MTB clades prevalent in Udupi district on the basis of SITVIT WEB analysis.

- Distribution of clades in three taluks of Udupi district, Karnataka, India.

Discussion

The largest cluster in the present study belonged to EAI1-SOM (SIT-48) shared by 14 (12.61%) clinical isolates. EAI1-SOM has earlier been also reported in variable prevalence from south India131415. East African Indian lineages originated in Guinea-Bissau (Africa) and believed to be transmitted to other continents through dispersion of modern humans from that region16. EAI1-SOM, a sublineage of EAI originated in Somalia, has been reported from India, with high prevalence in southern regions, whereas prevalence in northern regions of India is reported variably low1718. SIT-1942 (CAS1-Delhi) was the second largest cluster in the present study. CAS1-Delhi lineage supposed to be originated from India was later disseminated to regions such as Saudi Arabia, Kenya, South Africa, Malaysia, Myanmar, Australia, the USA and parts of Europe through frequent migration1920. Beijing, the East Asian lineage originated in China, is frequently reported to be associated with drug resistance and ubiquitously prevalent worldwide7. Low prevalence of Beijing has been reported (2.4-14.9%) in most studies in India except Mumbai (18.8%)21 and Assam (35.4%)22. It correlated with the presence of high drug resistance in these geographical regions. In the present study, it was found in about four per cent (4/111) of MTB isolates. One of these isolates, belonging to Beijing lineage, was detected as MDR. The low prevalence of Beijing lineage might be the possible reason for lesser number of multidrug resistance cases in Udupi district. MANU, an ancient lineage believed to be the probable ancestral of CAS and EAI with worldwide prevalence23, was found to be less prevalent (4.5%) in the present study. It was represented by SIT-100, which was initially reported from Delhi17. Some of the unique SITs found in this investigation, such as SIT-349, SIT-298, SIT-46, SIT-52, SIT-119, SIT-64 and SIT-1952, have been reported earlier from north India17181920242526 and a few such as SIT-256, SIT-138 and SIT-1268 have been reported from south India14152728. Spoligotypes of 31 clinical isolates from the present work did not match with the spoligo patterns available in SITVIT WEB database, suggesting the high evolutionary pressure on the isolates in this region which resulted in emergence of newer spoligotypes. Clustering of isolates was not found significantly associated with any of demographic variables and drug resistance patterns due to limited sample size. IS6110-RFLP analysis was considered as the gold standard for genotyping of MTB29. However, MIRU-VNTR typing has now been considered as the new molecular reference tool for being simpler, faster, less DNA demanding and with a similar resolution than RFLP typing30. We preferred spoligotyping as MIRU-VNTR typing was an expensive technique for limited resource laboratory like ours.

Although this was one of the first genotyping studies on clinical isolates of MTB in Udupi district of Karnataka, limited number of isolates and the inability to perform MIRU-VNTR typing were the major limitations.

In conclusion, our study showed the presence of highly diverse patterns of spoligotypes in Udupi district. High number of orphans (28%) in this study highlights the presence of a large number of genotypes which are yet to be identified. Longitudinal studies need to be done in this region to understand the transmission dynamics of MTB using different genotyping methods.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to Shri Vijay Dua and Shrimati Rajani K, for help in experimental work.

Financial support & sponsorship: None

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Global tuberculosis report. 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic markers, genotyping methods & next generation sequencing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:761-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methodological and clinical aspects of the molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016;29:239-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: Interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2607-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of drug resistance in pulmonary tuberculosis cases in South Coastal Karnataka. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015;5:275-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:907-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- SITVITWEB - A publicly available international multimarker database for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:755-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strain families using spoligotypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2006;6:491-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation and strategy for use of MIRU-VNTR plus, a multifunctional database for online analysis of genotyping data and phylogenetic identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2692-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- MIRU-VNTR plus: A web tool for polyphasic genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W326-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: An application of Simpson's index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2465-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity and drug susceptibility profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from different regions of India. J Infect. 2015;71:207-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Kerala, India using IS6110-RFLP, spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTRs. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;16:157-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spoligotype patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from extra pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Puducherry, India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2015;33:267-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:230-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic biodiversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in India. Infect Genet Evol. 2007;7:441-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predominant tuberculosis spoligotypes, Delhi, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1138-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypic diversity & drug resistance mutations in Varanasi, North India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:892-902.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predominance of Beijing genotype in extensively drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi, India. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2013;2:109-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Western Maharashtra, India, exhibit a high degree of diversity and strain-specific associations with drug resistance, cavitary disease, and treatment failure. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3593-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Assam, India: Dominance of Beijing family and discovery of two new clades related to CAS1_Delhi and EAI family based on spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTR typing. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145860.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex genetic diversity: Mining the fourth international spoligotyping database (SpolDB4) for classification, population genetics and epidemiology. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from North Indian patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2013;93:75-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of spoligotyping and IS6110-RFLP in assessing genetic diversity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in India. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:346-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a rural area of Kanpur by spoligotyping and mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs) typing. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:621-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Drug resistance among different genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from patients from Tiruvallur, South India. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:980-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modern and ancestral genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from Andhra Pradesh, India. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality assessment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotyping in a large laboratory network. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1210-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposal for standardization of optimized mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit-variable-number tandem repeat typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4498-510.

- [Google Scholar]