Translate this page into:

Factors associated with knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis & distress in cancer patients receiving palliative care – A retrospective cohort analysis

For correspondence: Dr Sundaramoorthy Chidambaram, Department of Psycho-oncology, Cancer Institute (WIA), No. 38, Sardar Patel Road, Adyar, Chennai 600 036, Tamil Nadu, India e-mail: vs.sunderc@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Demographic attributes of cancer patients are associated with the awareness of diagnosis, the prognosis of cancer and their associated psychological distress. This study was aimed to assess the knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and psychological distress among patients reporting to the pain and palliative care department in a tertiary cancer hospital, south India.

Methods:

Data of all patients visiting the palliative care outpatient department of a tertiary cancer centre in south India between January and June 2018 were included in the study (n=754). A structured pro forma was used to collect information on the sociodemographic details and clinical aspects and a distress thermometer was used to assess the level of distress. Information, thus collected, were analysed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression.

Results:

Around 16.2 per cent of the patients were unaware of their diagnosis while two third (68%) were unaware of the prognosis. More than half of the patients reported significant distress (54.1%). Gender, education, not working and being diagnosed with head-and-neck cancers were associated with knowledge of diagnosis, while educational level predicted the knowledge of prognosis. Younger age group, head-and-neck cancer, haematology cancer, state of being unaware of diagnosis and prognosis were found to be associated with distress.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Higher educational levels and better socio-economic status increase the likelihood of patients being aware of their diagnosis and prognosis. Being unaware of the prognosis remains associated with the higher level of distress.

Keywords

Advanced cancer

demographics

diagnosis

distress

palliative care

prognosis

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, cancer is the second leading cause of death globally and was responsible for an estimated 10 million deaths in 20201. An estimated number of cancer cases in India for the year 2022 was found to be 14,61,4272. In Tamil Nadu (a southern State in India), about 93,536 new cases were registered and 50,841 deaths occurred in 20223,4. The higher cancer incidence and poor prognosis in lower- and middle-income countries like India are attributable to lack of education, late diagnosis, inequitable access to affordable curative services leading to financial burden, insufficient policies of the government and lack of awareness about treatment options5. There is also substantial variability in the type of treatment available across various states in India6.

Distress in a cancer patient is attributable to numerous factors. Studies have shown that distress due to cancer is greater among women and those with low levels of education7,8. People with low levels of education reported advanced stage cancer at presentation9. Chronic diseases such as cancer require continued follow up, which in the scenario of pre-existing financial problems makes it difficult for patients and their families to cope8. In India, financial constraints were reported to be one of the main reasons for the delay in seeking help despite suspicion of cancer9. The place of stay also causes the difference in the level of distress and the awareness of diagnosis and prognosis. Patients who live in remote/rural areas often report to hospitals at an advanced stage of disease10.

The knowledge of the diagnosis and prognosis has been reported as a strong determinant of distress in the cancer settings. However, the opportunity of disclosing a diagnosis to patients or caregivers is not always feasible in a country like India, due to cultural factors and stigma attached to the diagnosis11. Caregivers in the Indian setting withhold information regarding the diagnosis and prognosis from the patients to buffer their distress. Caregivers believe that disclosing the diagnosis and prognosis may affect a patient’s illness negatively resulting in stress, depression, loss of hope and confidence12. In addition, cultural factors also seem to play a role in the practice of disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis of cancer to the patient. Although there are extensive literatures on the factors contributing to distress among cancer patients, reliable data linking demographic factors with awareness on diagnosis and prognosis is limited13,14. This retrospective study was undertaken to analyse the relationship of demographic factors with the knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and levels of distress among cancer patients.

Material & Methods

Design and sampling: This retrospective study was conducted at the outpatient department (OPD) of Pain and Palliative Care (PPC), Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, a tertiary cancer centre in south India. Demographic data were obtained from the electronic medical records (Indian Cancer Registry (IcanR) - an online database of JivDaya foundation - an NGO that was funding palliative care at cancer institute) of patients with cancer, irrespective of diagnosis and stage of the disease. All consecutive patients, who attended the OPD during January through June 2018, were included.

Data variables, sources of data and data collection: Data were collected from the patients (older than 18 yr) visiting PPC OPD during the study period, using a structured case record form (CRF) of IcanR, which was developed and validated with the help of subject experts. All the assessments were conducted directly with the patients during their first visit to the PPC OPD by a trained social worker who was part of the PPC and were documented. Although the data were collected on the first visit to the PPC clinic, the patients were under prior hospital care for other modalities of treatment. The IcanR is a private database developed exclusively by Jiv Daya for tracking and documenting the patients from hospitals collaborating with the foundation. The CRF of the IcanR contains information on the sociodemographics, disease-related information, knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and distress. The distress was assessed using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network distress thermometer (DT)15. The DT is a self-assessing one-item 11-point Likert scale displayed as a visual graphic of a thermometer that ranges from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress), wherein patients rate their level of distress, the week before assessment. A score of ≥4 on DT indicates moderate-to-severe distress. The distress assessment was carried out in the local language (Tamil) which is a translated version, face validated with experts for routine clinical assessment within the institute. With respect to the awareness of diagnosis and prognosis, all the patients were asked the following questions during their first visit. ‘Can you tell the name of the diagnosis?’ for assessing the knowledge of diagnosis and ‘Are you aware of the likely disease course (prognosis)?’ to assess the knowledge of prognosis. The responses were categorized as aware and unaware. Those patients, who were able to state the name of the diagnosis correctly, were considered as aware of diagnosis and patients, who were able to state the current outcome of the disease were considered as aware of prognosis. As these assessments are part of routine clinical care, all the data are collected mandatorily and documented robustly without any missing information.

Statistical analysis: The data collected were entered and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 20.0, released 2011, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). The socio-demographic and clinical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was performed to find the association of socio-demographic variables with knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and DT score. Binary logistic regression was used to examine the association between socio-demographic variables (age, gender and level of education) and distress (no distress <4; significant distress ≥4), knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis (aware and unaware). The significance level for all analyses was set at P<0.05, two tailed.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics: Of the 764 cancer patients visiting the OPD of PPC during the study period, 10 were excluded as they were minors (below 18 yr) and 754 were included for analysis. The sociodemographic characteristics are summarized in Table I. More than half of the patients (53.4%) were male with 69.5 per cent were between 41 and 65 yr. The patients’ mean age was 53.78 yr (standard deviation ± 12.79). Around 47.5 per cent patients had completed their secondary level of education, while 23 per cent had not received any formal education. More than half of the patients (56.4%) were unemployed; 57.4 per cent hailed from urban settings. The monthly income was below ₹ 5000 for nearly 56.4 per cent of patients; head-and-neck cancer (21.4%), breast (19.4%) and gastrointestinal (17.5%) cancers were the most commonly reported diagnosis in our cohort.

| Characteristics | Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 53.98±12.79 |

| Age (yr) | |

| 18-40 | 110 (14.6) |

| 41-65 | 524 (69.5) |

| 65+ | 120 (15.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 403 (53.4) |

| Female | 351 (46.6) |

| Education | |

| No formal education | 172 (22.8) |

| Primary school | 156 (20.7) |

| Middle school | 305 (40.5) |

| High school | 53 (7) |

| Graduate | 68 (9) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 425 (56.40) |

| Employed | 329 (43.6) |

| Income ( ₹) | |

| Below 5000 | 425 (56.4) |

| 5001-10,000 | 201 (26.7) |

| 10,001-20,000 | 73 (9.7) |

| Above 20,000 | 55 (7.3) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 321 (42.6) |

| Urban | 433 (57.4) |

| Cancer types | |

| Head and neck | 161 (21.4) |

| Breast | 112 (19.4) |

| Lung | 71 (9.4) |

| Gastrointestinal | 132 (17.5) |

| Gynaecology | 73 (9.7) |

| Haematology | 24 (3.2) |

| Unknown primary | 40 (5.3) |

| Others | 141 (18.7) |

SD, standard deviation

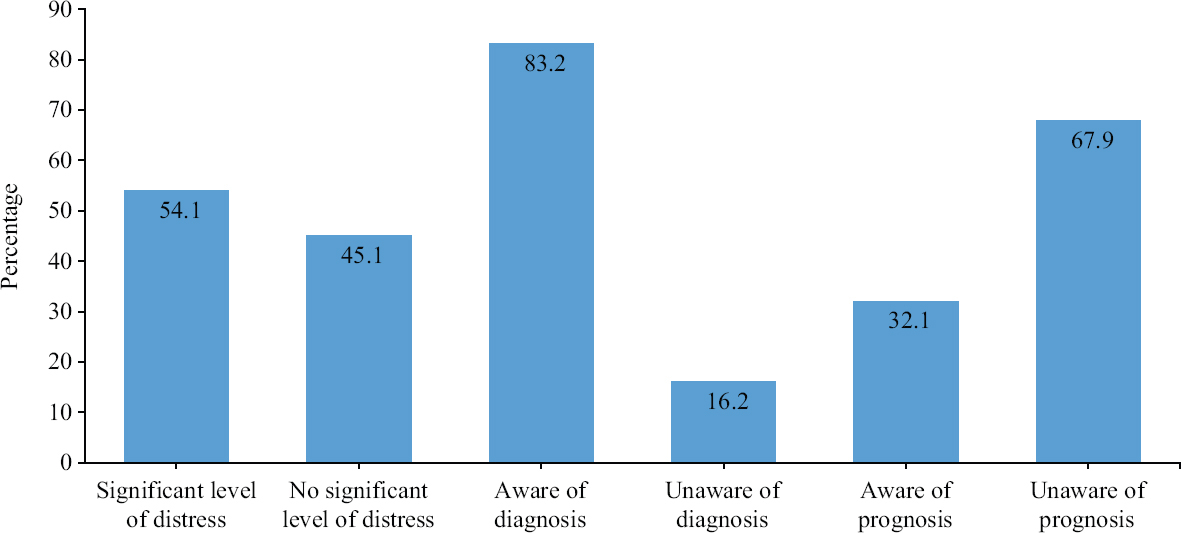

Prevalence of distress, knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis: The DT scores had a median value of 5 (range 0 to 10). Over half of the patients reported moderate-to-severe distress (54.1%). Most patients reported being aware of diagnosis (75%), but 68 per cent were unaware of their prognosis (Figure).

- Prevalence of distress and knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis.

Association between knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and level of distress with demographic characteristics: Knowledge of diagnosis was significantly associated with sociodemographic variables including gender (χ2 (1)=9.59, P<0.01), education (χ2 (4)=36.82, P<0.001), type of disease (χ2 (7)=30.10, P<0.001) and knowledge of prognosis (χ2 (1)=65.27, P<0.001). Knowledge of prognosis was significantly associated with socio-demographic variables including education (χ2 (4)=32.16, P<0.001), occupation (χ2 (1)=4.44, P<0.05) and income (χ2 (3)=15.10, P<0.01). Distress was significantly associated with sociodemographic variables, namely age (χ2 (2)=6.24, P<0.05), types of diseases (χ2 (7)=14.31, P<0.05), knowledge of diagnosis (χ2 (1)=3.28, P<0.05) and prognosis (χ2 (1)=11.91, P<0.001). Other sociodemographic variables were not significantly associated with distress (P>0.05) (Table II).

| Variables | Knowledge of diagnosis | Knowledge of prognosis | Distress score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware, n (%) | Unaware, n (%) | P | Aware, n (%) | Unaware, n (%) | P | <4, n (%) | ≥4, n (%) | P | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 351 (56) | 52 (40.9) | 0.001 | 138 (57) | 265 (51.8) | 0.101 | 189 (54.6) | 214 (52.5) | 0.301 |

| Female | 276 (44) | 75 (59.1) | 104 (43) | 247 (48.2) | 157 (45.4) | 194 (47.5) | |||

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| 18-40 | 95 (15.2) | 15 (11.8) | 0.097 | 44 (18.2) | 66 (12.9) | 0.090 | 39 (11.3) | 71 (17.4) | 0.044 |

| 41-65 | 440 (70.2) | 84 (66.1) | 166 (68.6) | 358 (69.9) | 246 (71.1) | 278 (68.1) | |||

| 65+ | 92 (14.7) | 28 (22) | 32 (13.2) | 88 (17.2) | 61 (17.6) | 59 (14.5) | |||

| Education | |||||||||

| No formal school | 126 (16.5) | 46 (36.2) | <0.001 | 39 (5.1) | 133 (26) | <0.001 | 88 (25.4) | 84 (20.6) | 0.428 |

| Primary school | 116 (15.2) | 40 (31.5) | 43 (5.6) | 113 (22.1) | 71 (20.5) | 85 (20.8) | |||

| Middle school | 276 (36.1) | 31 (24.4) | 100 (13.1) | 206 (40.2) | 130 (37.6) | 175 (42.9) | |||

| High school | 49 (6.4) | 5 (3.9) | 21 (2.7) | 32 (6.2) | 23 (6.6) | 30 (7.4) | |||

| Graduate | 63 (8.2) | 5 (3.9) | 40 (5.2) | 28 (5.5) | 34 (9.8) | 34 (8.3) | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 352 (56.1) | 73 (57.5) | 0.43 | 123 (50.8) | 302 (59) | 0.021 | 199 (57.5) | 226 (55.4) | 0.304 |

| Employed | 275 (43.9) | 54 (42.5) | 119 (49.2) | 210 (41) | 147 (42.5) | 182 (44.6) | |||

| Income ( ₹) | |||||||||

| Below 5000 | 353 (56.3) | 72 (56.7) | 0.552 | 128 (52.9) | 297 (58) | 0.002 | 187 (54) | 238 (58.3) | 0.647 |

| 5001-10,000 | 167 (26.6) | 34 (26.8) | 56 (23.1) | 145 (28.3) | 99 (28.6) | 102 (25) | |||

| 10,001-20,000 | 58 (9.3) | 15 (11.8) | 29 (12) | 44 (8.6) | 35 (10.1) | 38 (9.3) | |||

| Above 20,000 | 49 (7.8) | 6 (4.7) | 29 (12) | 26 (5.1) | 25 (7.2) | 30 (7.4) | |||

| Residence | |||||||||

| Rural | 264 (42.1) | 57 (44.9) | 0.315 | 105 (43.4) | 216 (42.2) | 0.408 | 158 (45.7) | 163 (40) | 0.066 |

| Urban | 363 (57.9) | 70 (55.1) | 137 (56.6) | 296 (57.8) | 188 (54.3) | 245 (60) | |||

| Types of cancer | |||||||||

| Head and neck | 148 (23.6) | 13 (10.2) | 0.001 | 52 (21.5) | 109 (21.3) | 0.336 | 80 (19.6) | 81 (23.4) | 0.046 |

| Breast | 95 (15.2) | 17 (13.4) | 41 (16.9) | 71 (13.9) | 61 (15) | 51 (14.7) | |||

| Lung | 58 (9.3) | 13 (10.2) | 17 (7) | 51 (10.5) | 40 (9.8) | 31 (9) | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 104 (16.6) | 28 (22) | 39 (16.1) | 93 (18.2) | 69 (16.9) | 63 (18.2) | |||

| Gynaecology | 61 (9.7) | 12 (9.4) | 25 (10.3) | 48 (9.4) | 37 (9.1) | 36 (10.4) | |||

| Haematology | 21 (3.3) | 3 (2.4) | 6 (2.5) | 18 (3.5) | 7 (1.7) | 17 (4.9) | |||

| Unknown | 23 (3.7) | 3 (13.4) | 9 (3.7) | 31 (6.1) | 23 (5.6) | 17 (4.9) | |||

| Primary | 117 (18.7) | 24 (18.9) | 53 (21.9) | 88 (17.2) | 91 (22.3) | 50 (14.5) | |||

| Others | |||||||||

| Knowledge of diagnosis | |||||||||

| Unaware | - | - | 2 (0.8) | 125 (24.4) | <0.001 | 49 (14.2) | 78 (19.1) | 0.043 | |

| Aware | - | - | 240 (99.2) | 387 (75.6) | 297 (85.8) | 330 (80.9) | |||

| Knowledge of prognosis | |||||||||

| Unaware | - | - | - | - | 257 (74.3) | 255 (62.5) | <0.001 | ||

| Aware | - | - | - | - | 89 (25.7) | 153 (37.5) | |||

<4 score, non-significant distress; ≥4 score, significant distress

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression: The simple logistic regression analysis showed that distress was significantly associated with age and type of cancer, knowledge of diagnosis with gender, age, education and type of cancer and knowledge of prognosis with age, education, occupation and income (P<0.05). The variables that were associated with distress, knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis in simple logistic regression analyses, were included in multivariate logistic regression for a final model predicting distress, knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis (Table III). In the multivariate logistic analysis, patients between 18-40 yr, with head and neck and haematology cancers, who were unaware of diagnosis and prognosis had an increased adjusted odds of distress. Males with no formal or only primary education, with head and neck cancer and unknown primary was associated with a low level of knowledge of the diagnosis. No formal education or primary and middle level of education were associated with low levels of knowledge of prognosis (Table IV).

| Variables | Knowledge of diagnosis (unaware/aware) | Knowledge of diagnosis (unaware/aware) | Distress score (<4 score/≥4 score) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI 95%) | P | OR (CI 95%) | P | OR (CI 95%) | P | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.48 (0.30-0.78) | 0.003 | 1.23 (0.90-1.68) | 0.176 | 0.91 (0.68-1.22) | 0.551 |

| Female (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| 18-400 | 1.92 (0.96-3.84) | 0.062 | 1.83 (1.05-3.19) | 0.033 | 1.88 (1.10-3.19) | 0.019 |

| 41-65 | 1.59 (0.98-2.58) | 0.058 | 1.27 (0.81-1.98) | 0.284 | 1.16 (0.78-1.73) | 0.442 |

| 65+ (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Education | ||||||

| No formal school | 0.21 (0.82-0.57) | 0.002 | 0.20 (0.11-0.37) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.54-1.67) | 0.871 |

| Primary school | 0.23 (0.86-0.61) | 0.003 | 0.26 (0.14-0.48) | <0.001 | 1.19 (0.67-2.11) | 0.536 |

| Middle school | 0.70 (0.26-1.87) | 0.480 | 0.33 (0.19-0.57) | <0.001 | 1.34 (0.79-2.28) | 0.269 |

| High school | 0.76 (0.20-2.78) | 0.681 | 0.45 (0.22-0.95) | 0.037 | 1.30 (0.63-2.68) | 0.471 |

| Graduate or above (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.94 (0.64-1.39) | 0.781 | 0.71 (0.52-0.97) | 0.035 | 0.91 (0.68-1.22) | 0.558 |

| Employed (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Income ( ₹) | ||||||

| Below 5000 | 0.60 (0.24-1.45) | 0.258 | 0.38 (0.21-0.68) | 0.001 | 1.06 (0.60-1.86) | 0.838 |

| 5001-10,000 | 0.60 (0.23-1.51) | 0.281 | 0.34 (0.18-0.63) | 0.001 | 0.85 (0.47-1.56) | 0.618 |

| 10,000-20,000 | 0.47 (0.17-1.31) | 0.151 | 0.59 (0.29-1.19) | 0.145 | 0.90 (0.44-1.82) | 0.780 |

| Above 20,000 (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cancer type | ||||||

| Head and neck | 2.33 (1.14-4.78) | 0.020 | 0.79 (0.49-1.27) | 0.336 | 0.54 (0.34-0.86) | 0.010 |

| Breast | 1.14 (0.58-2.25) | 0.693 | 0.95 (0.57-1.60) | 0.873 | 0.65 (0.39-1.09) | 0.105 |

| Lung | 0.91 (0.43-1.92) | 0.816 | 0.52 (0.27-0.99) | 0.048 | 0.70 (0.39-1.26) | 0.247 |

| Gastro | 0.76 (0.41-1.39) | 0.379 | 0.69 (0.42-1.15) | 0.161 | 0.60 (0.37-0.97) | 0.040 |

| Gynecology | 1.04 (0.48-2.22) | 0.914 | 0.86 (0.47-1.56) | 0.630 | 0.56 (0.31-1.00) | 0.051 |

| Hematology | 1.43 (0.39-5.20) | 0.582 | 0.55 (0.20-1.48) | 0.239 | 0.22 (0.08-0.58) | 0.002 |

| Unknown primary | 0.27 (0.12-0.59) | 0.001 | 0.48 (0.21-1.09) | 0.080 | 0.74 (0.36-1.52) | 0.417 |

| Others (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Urban (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Knowledge of diagnosis | ||||||

| Unaware | - | - | - | - | 1.43 (0.97-2.11) | 0.071 |

| Aware | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Knowledge of prognosis | ||||||

| Unaware | - | - | - | - | 0.57 (0.42-0.79) | 0.001 |

| Aware | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

| Variables | Knowledge of diagnosis (unaware/aware) | Knowledge of diagnosis (unaware/aware) | Distress score (<4 score/≥4 score) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 2.16 (1.35-3.46) | 0.001 | ||||

| Female (reference) | 1 | |||||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| 18-40 | 1.84 (1.06-3.18) | 0.029 | ||||

| 41-65 | 1.16 | |||||

| 65+ (reference) | 1 | |||||

| Education | ||||||

| No formal school | 0.15 (0.05-0.42) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.13-0.52) | <0.001 | ||

| Primary school | 0.17 (0.63-0.49) | 0.001 | 0.33 (0.17-0.64) | <0.001 | ||

| Middle school | 0.41 (0.23-0.75) | 0.001 | ||||

| High school | ||||||

| Graduate (reference) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Income ( ₹) | ||||||

| Below 5000 | ||||||

| 5001-10,000 | 0.50 (0.26-0.99) | 0.048 | ||||

| 10,001-20,000 | ||||||

| Above 20,000 (reference) | 1 | |||||

| Types of cancer | ||||||

| Head and neck | 2.53 (1.20-5.33) | 0.015 | 0.57 (0.36-0.92) | 0.022 | ||

| Breast | ||||||

| Lung | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||

| Gynaecology | ||||||

| Haematology | 0.22 (0.08-0.57) | 0.002 | ||||

| Unknown primary | 0.26 (0.11-0.59) | 0.001 | ||||

| Others (reference) | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Knowledge of prognosis | ||||||

| Unaware | 0.59 (0.43-0.82) | 0.001 | ||||

| Aware | 1 | |||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Discussion

This study focused on awareness about cancer diagnosis, prognosis and distress and identified sociodemographic and other factors associated with them using a retrospective descriptive study design. The major strength of this study rests with its large sample size and robust data. More than half of the cancer patients had reported moderate-to-severe distress and were unaware of their prognosis. Gender, education, type of cancer and knowledge of diagnosis were significantly associated with distress. Knowledge of diagnosis was significantly associated with gender, education and type of disease. However, knowledge of prognosis was significantly associated with sociodemographic variables including education, occupation and income. Younger age group, head-and-neck cancer, haematology cancer, the state of being unaware of diagnosis and prognosis were identified as factors associated with distress.

Our study revealed that more than half of the patients were experiencing moderate-to-severe distress and had poor knowledge of prognosis. A study conducted on cancer patients at Bangalore by Bandiwadeker et al16 revealed that 22-50 per cent of the patients reported a significant level of distress. This study reported that the patients between 18 and 40 yr, with head and neck and haematology cancers, who were unaware of diagnosis and prognosis had an increased adjusted odds of distress. This finding related to age and lung cancer is consistent with the result generated through an earlier cross-sectional study17.

Poor knowledge of prognosis was prevalent in our cohort as was in earlier literature indicating that divulging details of treatment and prognosis is seldom encouraged in India18. Ghoshal et al12 reported that patients actually preferred to know treatment details, but according to Applebaum et al19, patients were often not provided with the details of prognosis in India and this was perceived to be due to interdependence of family members and respect for elders.

Our study showed that men were more aware of their diagnosis. This is often the case, especially in India where a male member is first told about the diagnosis or prognosis20. A few studies have reported that women with advanced cancer develop more accurate understanding of their diseases than men do. This is attributed to in-depth discussions that women tend to have with their families, regarding their diagnosis than men, unlike in India21,22. This difference in the result could be attributed to the cultural context, where men in India often do not allow women to discuss about their diseases with physicians and other health care professionals and also try to hide the truth from women as they are uncertain of their emotional resilience23.

It is evident that there is a significant association between age and knowledge of the diagnosis. This study revealed that younger age group was unaware of the diagnosis. In a focus group study, Cartwright et al24 generated similar findings and stated that the patients often did not understand the prognostic information given to them and preferred not to know about the prognosis and that there was no concordance between healthcare provider’s explanation and patients’ understanding.

In line with the existing literature12, our study found that the patients with no formal education or low levels of education (<8th std) had poor or no knowledge of diagnosis and prognosis. Despite being diagnosed and treated in a cancer centre, our patients seemed to lack understanding of the term ‘cancer’ and its impact. Majority of the patients with below middle school education level had significant distress. As indicated by other researchers, having poor knowledge of diagnosis leads to poor quality of life, anxiety, depression and distress8,25. A study by Engelman et al26 stated that lack of awareness and education among the population caused uncertainty about the diagnosis, thereby leading to high distress.

People from low-middle socio-economic status in our cohort, were ignorant about their health condition with poor knowledge on their prognosis. Other researchers reported similarly that the poorer people did not report to hospitals, even though they were at early stages, due to poor financial condition and as they were the only breadwinner of the family9. A study by Fagundes et al25 was in line with this finding and also identified that poor socio-economic status was associated with depression severity.

Female patients in our cohort had a slightly lower level of significant distress compared to their male counterparts; however, Jacobsen et al27 claimed increased perception of distress in women due to emotional, family and physical concerns.

This study had a few limitations. Firstly, we did not include paediatric cancer patients, particularly the teenage population. Second, the study did not delve into the details of distress precluding in-depth analysis.

Overall, this study highlights the association of sociodemographic factors with knowledge of diagnosis, prognosis and the level of distress. Although patients were widely aware of the diagnosis, detailed knowledge on prognosis was limited. Male gender, higher educational level and better socio-economic status increased the likelihood of patients being aware of their diagnosis and prognosis. Being unaware of prognosis was associated with the increased level of distress. The findings of this study emphasize the need for disclosure of prognosis to patients; professional training on cancer communication for medical professionals should be mandated so that adequate informational support for patients and families could be assured. Further, studies focusing on barriers to disclosing news to the patients and the detailed cause of distress may through more light on necessary intervention.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Jiv Daya Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgment:

The authors acknowledge Ms Revathy Sudhakar for assistance towards editing the manuscript.

References

- Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer incidence estimates for 2022 &projection for 2025: Result from National Cancer Registry Programme, India. Indian J Med Res. 2022;156:598-607.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Rising cases of cancer. Available from: https://pqals.nic.in/annex/1711/AU1436.pdf

- The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Death cases of cancer. Available from: https://pqals.nic.in/annex/1710/AU1809.pdf

- Palliative care in India: Current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care. 2012;18:149-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden of cancers and their variations across the states of India: The Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1289-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- An observational study to assess the socioeconomic status and demographic profile of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care in a tertiary-level cancer hospital of Eastern India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:496-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of different sociodemographic factors on mental health status of female cancer patients receiving chemotherapy for recurrent disease. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018;24:426-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social, demographic and healthcare factors associated with stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer: Cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Northern Uganda. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e007690.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographical location and stage of breast cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of the literature. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:1357-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Does the cancer patient want to know?Results from a study in an Indian tertiary cancer center. South Asian J Cancer. 2013;2:57-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- To tell or not to tell: Exploring the preferences and attitudes of patients and family caregivers on disclosure of a cancer-related diagnosis and prognosis. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accounts of carers'satisfaction with health care at the end of life: A comparison of first generation black Caribbeans and white patients with advanced disease. Palliat Med. 2001;15:337-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med. 2007;21:145-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distress management, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1229-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of distress among cancer patients in Bengaluru city : A cross-sectional study. Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2020;18:92-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethical dilemmas in palliative care in traditional developing societies, with special reference to the Indian setting. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:611-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conceptualizing prognostic awareness in advanced cancer: A systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2014;19:1103-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary family caregivers'reasons for disclosing versus not disclosing a cancer diagnosis in India. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43:126-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gender differences in the evolution of illness understanding among patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2013;11:126-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer stage knowledge and desire for information: Mismatch in Latino cancer patients? J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:458-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Breaking bad news: Patient preferences and the role of family members when delivering a cancer diagnosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:1779-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer patients'understanding of prognostic information. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:311-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Socioeconomic status is associated with depressive severity among patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Treatment setting and minority status do not make a difference. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1459-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103:1494-502.

- [Google Scholar]