Translate this page into:

Effectiveness of isoniazid preventive therapy on incidence of tuberculosis among HIV-infected adults in programme setting

For correspondence: Dr C. Padmapriyadarsini, ICMR-National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, No. 1, Mayor Sathyamoorthy Road, Chetput, Chennai 600 031, Tamil Nadu, India e-mail: pcorchids@gmail.coms

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

As India and other developing countries are scaling up isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) for people living with HIV (PLHIV) in their national programmes, we studied the feasibility and performance of IPT in terms of treatment adherence, outcome and post-treatment effect when given under programmatic settings.

Methods:

A multicentre, prospective pilot study was initiated among adults living with HIV on isoniazid 300 mg with pyridoxine 50 mg after ruling out active tuberculosis (TB). Symptom review and counselling were done monthly during IPT and for six-month post-IPT. The TB incidence rate was calculated and risk factors were identified.

Results:

Among 4528 adults living with HIV who initiated IPT, 4015 (89%) successfully completed IPT. IPT was terminated in 121 adults (3%) due to grade 2 or above adverse events. Twenty five PLHIVs developed TB while on IPT. The incidence of TB while on IPT was 1.17/100 person-years (p-y) [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8-1.73] as compared to TB incidence of 2.42/100 p-y (95% CI 1.90-3.10) during the pre-IPT period at these centres (P=0.017). The incidence of TB post-IPT was 0.64/100 p-y (95% CI 0.04-1.12). No single factor was significantly associated with the development of TB.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Under programmatic settings, completion of IPT treatment was high, adverse events minimal with good post-treatment protection. After ruling out TB, IPT should be offered to all PLHIVs, irrespective of their antiretroviral therapy (ART) status. Scaling-up of IPT services including active case finding, periodic counselling on adherence and re-training of ART staff should be prioritized to reduce the TB burden in this community.

Keywords

Antiretroviral therapy

IPT

people living with HIV

programmatic settings

tuberculosis prevention

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to remain the most common cause of morbidity and mortality among people living with HIV (PLHIVs), even in the era of antiretroviral therapy (ART)1. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that about 10.4 million people fell ill with TB in 2016, of whom, 10 per cent were PLHIVs, with 374,000 TB deaths reported among PLHIVs2. India accounted for 26 per cent of the combined total TB deaths in HIV-negative and HIV-positive people2. Further, in 2015, when this study was done, the estimated national adult (15-49 yr) seroprevalence of HIV/AIDS was 0.26 per cent (0.22-0.32%), with an estimated 2.1 million (1.7-2.6 million) PLHIVs in India3. As in other developing countries, TB is the most common opportunistic infection among PLHIVs in India, with an incidence varying between 2.2 and 3.3 cases/100 person-years (p-y)4.

The WHO recommends intensified case finding, isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) and infection control, besides the early initiation of ART, to reduce the burden of TB among PLHIVs5. The revised guidelines also emphasize that a tuberculin skin test (TST) is not a requirement for initiating IPT in PLHIV5. Despite the strong recommendations globally, the uptake of IPT for the prevention of TB among PLHIVs has been limited. This is mainly due to the concerns about difficulties in excluding active TB disease, fear of added pill burden, poor adherence to IPT, associated side effects and fear of development of drug resistance678. A meta-analysis of studies found that the absence of all symptoms of cough, night sweats, fever or weight loss might identify a subset of PLHIVs with a very low probability of having TB disease, with a sensitivity of 79 per cent and a negative predictive value of 97.7 per cent [95% confidence interval (CI) 97.4-98.0]9. This high negative predictive value ensures that those who are negative on screening are unlikely to have TB and hence can reliably start IPT. The addition of a chest radiograph improved negative predictive value only marginally to 98 per cent. No studies have documented an increased incidence of rates of drug resistance solely attributable to IPT10. Successful models for IPT implementation under programmatic settings in high TB burden countries are also limited11.

One of the most common complications of isoniazid (INH) is the development of painful polyneuropathy (PN), which is preventable with adequate pyridoxine supplementation. PN is also the most common neurological complication associated with HIV infection, arising either as a complication of the disease itself or as an ART-related toxic neuropathy12. If unrecognized and untreated, severe and prolonged morbidity may result. Therefore, it is recommended that patients considered being at risk for developing INH-associated PN, such as those with alcohol habit, malnutrition, diabetes and HIV infection, receive daily pyridoxine supplementation13. Estimates of pyridoxine dosage needed to prevent INH-induced PN have varied widely from 6 to 50 mg/day, with safe levels of daily intake being approximately 100 times the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) 1-2 mg/day1314. The practice in most high-resource settings is to give 10-50 mg/day along with INH therapy14.

The objective of this multicentre study was to evaluate the feasibility of implementing IPT under field conditions and to assess its effectiveness in terms of compliance, treatment outcome, adverse event and post-IPT effect, when IPT was initiated at different CD4 cell counts, with or without ART, under real-life settings.

Material & Methods

This multicentre, prospective pilot study, to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of IPT in reducing the incidence of TB among PLHIV, was undertaken between July 2013 and February 2016 in seven ART centres located in urban and semi-urban cities of India [Tiruvallur (Government District Hospital); Chennai (Government Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital); Vellore (Government Vellore Medical College and Hospital); Madurai (Government Rajaji Medical College and Hospital); Krishnagiri (Government Headquarters Hospital), Mysuru (Ashakirana Hospital); Delhi (National Institute for TB and Respiratory Diseases)]. These sites were selected to represent both high and low burden of TB and HIV caseload, far away from one another to avoid selection bias of the participating sites to assess the feasibility of implementing IPT in all types of ART centre (high- and low-caseload centres).

Adult PLHIVs attending these centres were eligible to participate in the study if (i) they had documented evidence of HIV infections, (ii) they were 18 yr or above, (iii) there was no current evidence or suspicion of active TB disease, (iv) they were not currently on anti-TB treatment or TB preventive therapy, and (v) they were willing to adhere to the follow up schedule and study procedures. PLHIVs with critically ill or with current evidence of TB disease or with a history of seizure disorder or chronic liver disease or unwilling to comply with treatment or follow up schedule and/or alcohol dependence (assessed by the WHO's AUDIT scale >8)15 were excluded from the study enrolment.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis (NIRT), Chennai, and the participating site IECs. Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the respective State AIDS Control Society and the hospital scientific/advisory committees. Participants signed informed written consent.

Pre-isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) phase:

Enhanced TB surveillance, using the WHO's symptom-based screening algorithm (a current cough, fever, weight loss or night sweats), was carried out at all these sites for a period of six months before the initiation of the study45. PLHIVs who did not report any one of the symptoms of current cough, fever, weight loss or night sweats were considered unlikely to have active TB, while those who report any one of the above symptoms were suspected to have active TB and evaluated further for TB and other diseases. This was done to systematically record and report the incidence of TB among PLHIVs at these centres, before IPT introduction.

Isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) introduction: The selected ART sites started implementing IPT in a step-wise manner. All PLHIVs attending the ART centres were screened for TB using the symptom-based screening algorithm5. If PLHIVs were symptomatic, they were further evaluated by sputum smear microscopy and chest radiography or fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC)/biopsy, as appropriate. GeneXpert and culture were not part of routine TB screening for PLHIV in the national programme and hence were not done. If they were diagnosed with active TB disease, they were initiated on anti-TB treatment (ATT) as per the national guidelines. If PLHIVs were asymptomatic, they were assessed for initiating IPT. Wherever required, ART was initiated based on the national guidelines and standard of care. As per the revised WHO guidelines for intensified TB case finding and IPT for PLHIVs in resource-constrained settings, TST is not a requirement for initiating IPT5. Moreover, due to operational complexities such as the second visit for TST reading after 48-72 h, it was decided not to use TST in this study being done under programmatic settings.

All asymptomatic PLHIVs, with no current evidence of active TB disease and not currently on ATT, were considered eligible to receive IPT. They were initiated on IPT with 300 mg of INH along with 50 mg of pyridoxine to be taken daily. Given the co-existing conditions of malnutrition, HIV infection and alcoholism in our study population, which also contribute to peripheral neuropathy, we expected that a higher proportion of patients may develop painful peripheral neuropathy with INH; hence, a prophylactic dose of 50 mg pyridoxine was considered. The drugs were supplied for a month with instructions for follow up and refill.

Follow up: At each monthly review, PLHIVs were assessed for TB symptoms, side effects of INH, IPT adherence and doses missed since the last visit. Adherence to drugs was assessed by remaining doses of pills during the monthly clinic attendance, self-reporting and on-time pill pick-up. If there were no symptoms, they were offered brief supportive messages by the centre counsellor on the need for IPT (and ART), drug adherence, adverse events, TB symptoms, healthy nutrition and hygiene and provided with the following month's supply of drugs. This was continued every month for a period of six months.

A study from gold miners of South Africa has shown that the incidence of TB increased within six months of stopping IPT followed by a stable rate over time16. There was no evidence for changing risk factors for TB disease over time. Moreover, as PLHIVs were transferred to link/smaller ART centres once they became stable on ART, it was difficult to follow them beyond six months. Hence, it was decided to follow all PLHIVs for six months post-IPT.

Those with TB symptoms any time during follow up underwent further diagnostic tests to rule out active TB. Active TB was diagnosed if any of the sputum smear results became positive. If extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) was suspected, it was confirmed by fine-needle aspiration or biopsy and histopathology examination, whenever feasible. If TB was diagnosed, they were initiated on ATT as per the national guidelines. Liver function test was done only when clinically indicated (symptoms/signs compatible with hepatotoxicities such as jaundice, nausea and vomiting). IPT was discontinued in cases of severe peripheral neuropathy (WHO grade 3-4), severe rash or elevated liver enzymes to three times the upper limit of normal.

The occurrence of TB in the first month was considered as prevalent TB since the patients may have been cases of active TB missed during the symptom-based screening or possibility of TB-IRIS (Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome) during the first month with ART initiation or EPTB manifesting with boosting of immunity with ART and INH. Further, the need was felt for the effect of IPT to set in before considering incident TB while on IPT. Hence, TB during the first month of IPT was considered as prevalent TB. The effectiveness of IPT was measured as incidence of TB (events per 1000 p-y) among PLHIVs on IPT versus incidence of TB among PLHIVs, before IPT introduction in that centre. As patients had varying periods of follow up, the p-y calculation was done to estimate the TB incidence. The feasibility of providing IPT to PLHIV was measured by the proportion of patients receiving HIV care who had TB screening, proportion eligible for IPT, proportion initiated on IPT and the proportion who went on to complete six months of IPT. In addition, the proportion of PLHIVs who discontinued INH due to side effects was also noted.

Statistical analysis: The statistical analysis was done using SPSS statistical software, version 20.0 Armonk, (NY: IBM Corp., USA). Chi-square test was used to compare the incidence of TB between the periods. Chi-square test was used to estimate the relative risk, and Kaplan–Meir analysis was done to identify the incidence and risk factors for the development of TB among PLHIVs. As the number lost to follow up was minimal, no adjustments were done for lost-to-follow up samples.

Results

Enhanced TB surveillance: Results of the enhanced TB surveillance at the selected ART centres have been published elsewhere4. In brief, a prospective multicentre study was carried out in 10 ART centres in four States of India, to evaluate the effectiveness of WHO's symptom-based screening algorithm to exclude TB among PLHIVs. At these sites, provider-initiated active screening for TB (i.e., enhanced TB surveillance) was carried out using the above algorithm. Presumptive TB was considered if a patient had one or more of the following symptoms: any (current) cough, fever, drenching night sweats or unintentional weight loss. The symptom screening was done by a trained clinic staff and symptomatic was referred for further examination by sputum microscopy and chest X-ray for pulmonary TB while FNAC or tissue biopsy for extrapulmonary cases. A total of 6099 adult PLHIVs were screened for TB over six months. Of them, 1815 (30%) had at least one symptom suggestive of TB and 117 PLHIVs were diagnosed with TB. Of the 117 TB cases, 75 PLHIVs were on concomitant ART, while 42 were not receiving ART at the time of TB diagnosis. Overall, the prevalence of undiagnosed TB was 0.84 per 100 persons, and in the subsequent six months of screening, the incidence of TB was 2.4/100 p-y (95% CI 1.90-3.10)4.

During isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) phase

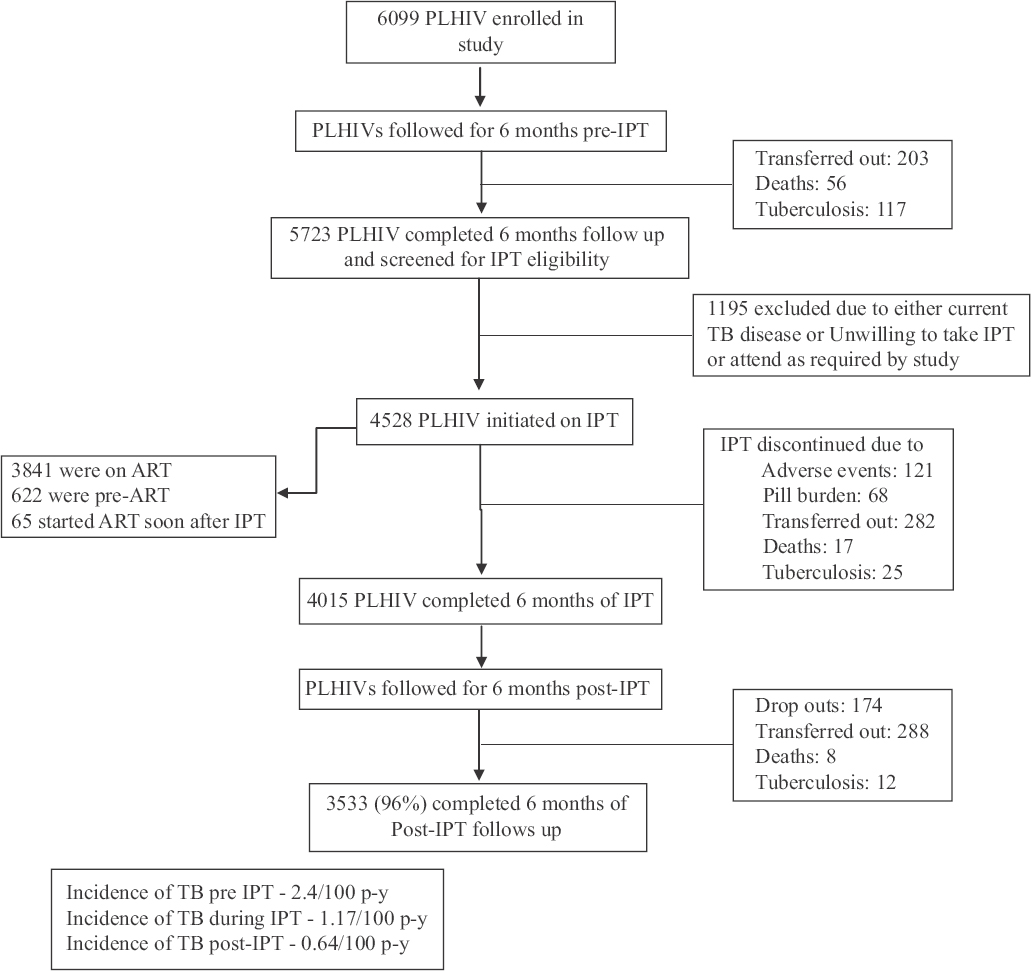

Baseline characteristics: Of the5723 PLHIVs screened, 4528 (80%) were initiated on IPT. Their median age was 36.0 [interquartile range (IQR) 31.0-42.0] yr and the median CD4 cell counts were 438 (IQR 272-643) cells/μl. 51 per cent (2311) were females. At the time of IPT initiation, 3841 (85%) PLHIVs were on ART, 622 (14%) were not on ART while 65 PLHIV started ART a few months after the initiation of IPT. The remaining 1195 PLHIVs did not initiate IPT as they either refused preventive therapy and study procedures or had TB at initial screening or were found ineligible for IPT initiation as per the study protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

- Flowchart showing people living with HIV (PLHIV) screened, initiated and completed isoniazid preventive therapy. ATT, antituberculosis treatment; ART, antiretroviral therapy; IPT, isoniazid preventive therapy.

Isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) initiation and follow up: Of the 4528 PLHIVs initiated on IPT, 4015 (89%) successfully completed 180 doses of IPT within nine months, based on their on-time clinic attendance for pill pick-up as marked in their pharmacy cards at the clinic and self-reporting. Sixty two PLHIVs discontinued IPT mid-way due to loss of interest, 282 dropped out as they were transferred out to peripheral ART centres where IPT was not available and patients did not want to travel to the main centre. During their monthly visits to the clinic to collect the monthly supply of IPT, pyridoxine and ART, they were screened for TB symptoms and for adverse events to IPT/ART.

Incidence rate of tuberculosis (TB)

During IPT: There occurred 25 new cases of TB in our study while on IPT during 2132.5 p-y of observation, making the overall TB incidence rate of 1.17/100 p-y (95% CI 0.8-1.73). Of these TB cases, 13 were pulmonary and 12 were EPTB. Among the 13 pulmonary TB cases, sputum smear was positive for acid-fast bacilli in eight patients, while five were diagnosed as smear-negative pulmonary TB based on chest X-ray and clinical symptoms. Culture and drug susceptibility tests were available only for four patients, and none of them showed INH resistance. Cervical TB lymphadenitis, as proven by histopathological examination, was the most common form of EPTB . Of the 25 TB cases during IPT, 20 were on concomitant ART while five PLHIVs were not receiving ART. Eleven of the 25 TB cases occurred at the end of the third month of IPT. Five cases occurred after five months, four after four months and three after two months of IPT. Two PLHIVs developed TB during their sixth month of IPT. The incidence of TB, while on IPT was 1.17/100 p-y (95% CI 0.8-1.73) as compared to TB incidence of 2.42/100 p-y (95% CI 1.90-3.10), found on screening 6099 PLHIV for six months during pre-IPT period at these centres, the difference being significant (P<0.001) (Table).

| Category | Total PLHIVs | Deaths | Incident TB cases | p-y | Incidence rate/100 p-y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No IPT | 6099 | 56 | 117 | 4834.7 | 2.42 |

| ART | 4746 | 35 | 75 | ||

| No ART | 1353 | 21 | 42 | ||

| IPT | 4528 | 17 | 25 | 2132.5 | 1.17** |

| IPT after ART | 3841 | 0 | 2 | 0.09 | |

| IPT only | 622 | 2 | 5 | 0.23 | |

| IPT before ART | 65 | 15 | 18 | 0.84 | |

| Post-IPT | 4015 | 8 | 12 | 1860.67 | 0.64 |

| ART | 3500 | 7 | 10 | 0.53 | |

| No ART | 515 | 1 | 2 | 0.12 |

**P<0.001 between no IPT versus IPT. IPT, isoniazid preventive therapy; ART, antiretroviral therapy; p-y, person-years

During post-isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) follow up: The 4015 PLHIVs (2046 females and 1969 males) who completed six months of IPT were further followed up for six-month post-IPT. Of these, 3553 (96%) completed the six-month post-IPT follow up, 87 per cent were on ART. During this period, 12 incident cases of TB during 1860.67 p-y of observation were noticed. Of them, there were seven sputum smear-positive pulmonary TB, two sputum smear-negative pulmonary TB and three EPTB. The TB incidence rate during six-month post-IPT was 0.64/100 p-y (95% CI 0.04-1.12). There were eight deaths, 288 transfer out to peripheral ART centres and 174 dropouts during this period (P=0.059).

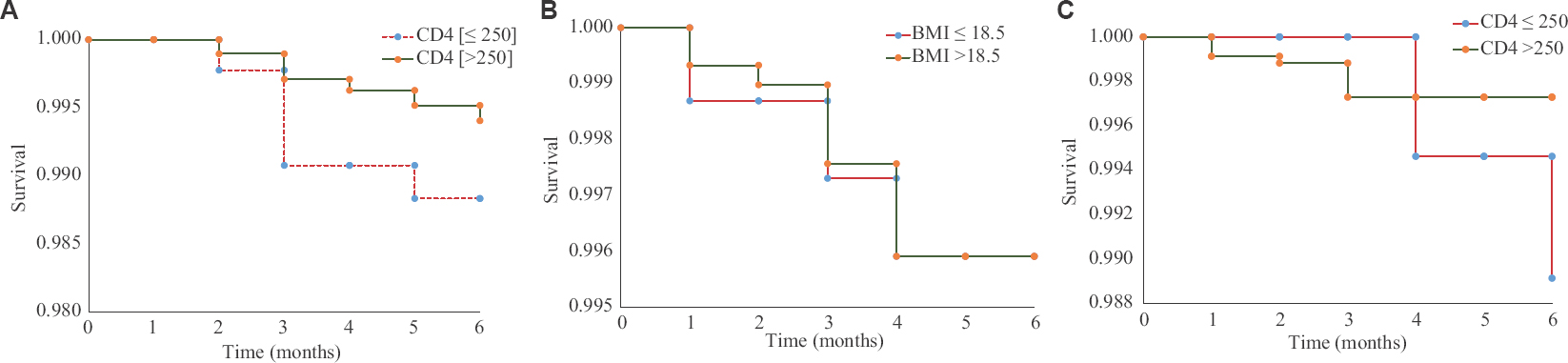

Risk factors of tuberculosis (TB): In our study, no particular factor was found to be significantly associated with the development of TB in PLHIV on IPT. Males [relative risk (RR)=0.88, 95% CI 0.40-1.93], body mass index >18.5 (RR=1.46, 95% CI 0.63-3.37) and patients not on ART (RR=1.52, 95% CI 0.57-4.04) showed increased risk of developing TB but did not reach significance. At the same time, PLHIV who did not complete the full course of IPT (RR=90.6, 95% CI 21.4-383), had a strong risk of developing TB. Kaplan–Meir analysis showed a higher risk of developing TB among PLHIV with a CD4 <250 cells/μl both during IPT (RR = 2.28, 95% CI 0.99-5.25) and post-IPT period, while those with BMI of <18.5kg/m2 had a higher risk of developing TB in the post-IPT phase unlike while on IPT (Fig 2).

- Kaplan–Meir analysis showing incidence of tuberculosis among people living with HIV by CD4 and body mass index. (A) During isoniazid preventive therapy phase. Post-isoniazid preventive therapy phase (B) CD4 and (C) body mass index.

Tolerability and adverse events: Adverse events were encountered in 121 (3%) PLHIVs. The most common adverse events were vomiting (35%) followed by skin rash (32%). The other adverse events included anaemia, chicken pox, convulsion, diarrhoea, drowsiness, headache, jaundice, numbness and stomach pain. Majority of the adverse events occurred after two months of IPT. In 18 patients, IPT had to be terminated due to toxicity and was mainly due to jaundice. Many of the adverse events such as vomiting (zidovudine or NRTIs), rash numbness (stavudine) and jaundice could have also been due to drug–drug interactions of INH with ART, and this was considered while managing these patients for the adverse events.

Serious adverse events: There were 17 deaths during the follow up, of which eight PLHIVs died during their fifth month of IPT. There was one death each due to jaundice, anaemia, renal failure and fever, while two deaths each due to myocardial infarction and accident. Cause of death was not known for the rest. Of these 17 patients, 15 were on ART with a median CD4 of 375 (IQR 178-594) cells/μl.

Discussion

Our study showed that active screening of PLHIV for TB and providing them with IPT were not only feasible but also successful as evidenced by the high rate of PLHIV who initiated IPT and completed it with minimal adverse events, similar to other settings1718. Further, the enhanced TB surveillance using symptom-screening algorithm was able to identify PLHIVs with presumptive TB, both pulmonary and extrapulmonary, and to send them for further investigations. There was almost a 50 per cent reduction in the incidence of TB among PLHIVs who received IPT with or without ART, as compared to the previous group of PLHIVs who did not receive IPT at these ART centres4. Similar results of the effectiveness of IPT in reducing TB incidence, under programmatic setting, have also been shown in other resource-limited countries1920. Majority of TB cases occurred among non-completers of IPT. The strength of this study was a six-month post-treatment follow up that showed protection from IPT for six-month post-IPT. The protection against TB among PLHIV was greater when IPT and ART given together rather than any single intervention given alone.

Overall, in this multicentre study, 79 per cent of PLHIV who underwent WHO's symptom-based screening algorithm started IPT. About 20 per cent of PLHIVs were excluded from the study enrolment mainly because they were found to have prevalent TB during screening or they were unwilling to take IPT or come for study visits. Exclusion rates for IPT initiation in PLHIVs vary from 12 to 35 per cent in other settings111920.

In our study, 89 per cent of PLHIVs initiating IPT completed it, comparable to rates in other IPT programmes1921. All participants received counselling, both prior and during monthly IPT refills, about adverse events, TB symptoms and disadvantages of treatment default. This helped us to achieve high treatment completion and minimal drop-out rates. Although PLHIVs were on ART both before and after IPT administration, the incidence of TB was lower in the six month post-IPT period as compared to the pre-IPT period. This evidence is an indirect surrogate of the prolonged benefit of IPT, at least for six month post-IPT while on ART.

In this study, adverse events attributable to IPT were less than five per cent. Vomiting and skin rash were the most common adverse events. Clinically detected hepatotoxicity, a potentially serious adverse event during IPT, was seen in <1 per cent of our population, unlike other studies that have reported around seven per cent of hepatotoxicity222324.

As reasons for non-participation in the study were not systematically collected, it was not possible to conclude the proportion of eligible persons who opted out of initiating IPT. High completion rates of IPT may partly have been due to the enrolment of only those voluntarily willing to participate in the study. IPT adherence was monitored only by self-reporting, and there was no surprise pill count or urine testing of INH. WHO's symptom-based screen algorithm that was used to rule out TB in this study has a negative predictive value of 98 per cent Hence, there is a probability of having missed a few EPTB cases among PLHIVs and them having received INH monotherapy. Therefore, proper screening to rule out TB is essential before initiating IPT. The six month post-IPT follow up may be inadequate in the light of findings on the durability of protection by IPT being lost within 6-12 months in settings with the high annual risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection16. Given the constraints of limited budget and long-term follow up under programmatic setting, only six month post-IPT follow up could be done. Future studies should plan for a longer duration of post-preventive therapy follow up to find the durability of TB preventive therapy in endemic settings.

To conclude, in ART centres, intensified case finding for TB, using WHO symptom-based screening tool should form part of routine HIV care. After ruling out TB, IPT should be offered to all PLHIVs, irrespective of their ART status. Periodic counselling for patients on adherence and re-training of ART centre staff are essential. This integrated efforts for improving TB case finding and offering IPT to eligible PLHIVs are critical for reducing TB morbidity and mortality among PLHIVs.

Acknowledgment

Authors thank the staff of Epidemiology unit of NIRT, Chennai (Sarvshri V. Partheeban, Sargunan, Nagaraj, Premkumar and Ramesh); Department of Biostatistics, Department of Clinical Research (Smt. Gunasundari, Stella Mary and Sakila Shankar) and all staff of participating ART centres. We thank the senior staff of the Central TB Division (Dr K.S. Sachdeva) and National AIDS Control Organization and all staff of the participating ART centres for their support and cooperation in the conduct of the study.

Financial support & sponsorship: Indian Council of Medical Research is acknowledged for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- The cursed duet today: Tuberculosis and HIV-coinfection. Presse Med. 2017;46:e23-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017.

- India HIV Estimation 2015. Technical Report. Available from: http://indiahivinfo.naco.gov.in/naco/resource/india-hiv-estimations-2015-technical-report

- Effectiveness of symptom screening and incidence of tuberculosis among adults and children living with HIV infection in India. Natl Med J India. 2016;29:321-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guideline for Intensified TB case-finding and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy for HIV positive patients in resource-constrained settings. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011.

- Implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV worldwide: Barriers and solutions. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 5):S57-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to and motivations for the implementation of a treatment program for latent tuberculosis infection using isoniazid for people living with HIV, in upper Northern Thailand. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:60-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers in the implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in Northern Ethiopia: A mixed quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:840.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of a standardized screening rule for tuberculosis in people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings: Individual participant data meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benefits of continuous isoniazid preventive therapy may outweigh resistance risks in a declining tuberculosis/HIV coepidemic. AIDS. 2016;30:2715-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is IPT more effective in high-burden settings? Modeling the effect of tuberculosis incidence on IPT impact. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21:60-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adverse events to antituberculosis therapy: Influence of HIV and antiretroviral drugs. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:339-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polyneuropathy, anti-tuberculosis treatment and the role of pyridoxine in the HIV/AIDS era: A systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:722-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of tuberculosis. Atlanta, GA, USA: American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2003.

- AUDIT, AUDIT-C, and AUDIT-3: Drinking patterns and screening for harmful, hazardous and dependent drinking in Katutura, Namibia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120850.

- [Google Scholar]

- The timing of tuberculosis after isoniazid preventive therapy among gold miners in South Africa: A prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2016;14:45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis outcomes and drug susceptibility in individuals exposed to isoniazid preventive therapy in a high HIV prevalence setting. AIDS. 2010;24:1051-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of isoniazid preventive therapy with lower early mortality in individuals on antiretroviral therapy in a workplace programme. AIDS. 2010;24:5-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Implementation and evaluation of an isoniazid preventive therapy pilot program among HIV infected patients in Vietnam, 2008-2010. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2015;109:653-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial effect of isoniazid preventive therapy and antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of tuberculosis in people living with HIV in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104557.

- [Google Scholar]

- Completion of isoniazid preventive therapy and survival in HIV-infected, TST-positive adults in Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1515-21, i.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatotoxicity associated with isoniazid preventive therapy: A 7-year survey from a public health tuberculosis clinic. JAMA. 1999;281:1014-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatotoxicity during isoniazid preventive therapy and antiretroviral therapy in people living with HIV with severe immunosuppression: A Secondary analysis of a multi-country open-label randomized controlled clinical trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78:54-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serious hepatotoxicity following the use of isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV patients in Eritrea. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2018;6:e00423.

- [Google Scholar]