Translate this page into:

Diversity of sandflies in Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, India, a region endemic to Chandipura virus encephalitis

For correspondence: Dr A.B. Sudeep, Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Virology, Microbial Containment Complex, Sus Road, Pashan, Pune 411 021, Maharashtra, India e-mail: sudeepmcc@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Sandflies are implicated as vectors of Chandipura virus (CHPV) (Vesiculovirus: Rhabdoviridae). The virus is prevalent in central India including Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. CHPV causes encephalitis in children below 15 yr of age with case fatality rates ranging from 56 to 78 per cent. The present study was undertaken to determine the sandfly fauna in the CHPV endemic Vidharba region.

Methods:

A year round survey of sandflies was conducted at 25 sites in three districts of Vidarbha region. Sandflies were collected from their resting sites using handheld aspirators and identified using taxonomical keys.

Results:

A total of 6568 sandflies were collected during the study. Approximately 99 per cent of the collection belonged to genus Sergentomyia, which was represented by Ser. babu, Ser. bailyi and Ser. punjabensis. Genus Phlebotomus was represented by Ph. argentipes and Ph. papatasi. Ser. babu was the predominant species (70.7%) collected during the study. Ph. argentipes was detected in four villages with 0.89 per cent, whereas Ph. papatasi was detected in only one village with 0.32 per cent of the total collection. CHPV could not be isolated despite processing all the sandflies for virus isolation in cell culture.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The present study showed influence of higher temperature and relative humidity on sandfly population dynamics. An important observation during the study was the absence or decline in the population of Ph. papatasi and Ph. argentipes in the study area. Surge in Sergentomyia population and their breeding/resting in close vicinity to humans pose a concern as they are known to harbour CHPV and other viruses of public health importance.

Keywords

Chandipura virus

Maharashtra

Phlebotomus

sandfly

Sergentomyia

Vidarbha

Sandflies are known to harbour a number of viruses of public health importance apart from their role in the transmission of Leishmania parasites. Female sandflies feed on humans and other vertebrate hosts, pick up infection while feeding and transmit to susceptible hosts after an extrinsic incubation period1. More than 50 sandfly borne viruses, mainly belonging to genus Phlebovirus, have been identified as human pathogens1,2. Chandipura encephalitis, a disease caused by Chandipura virus (CHPV) (Rhabdoviridae: Vesiculovirus), is the most significant sandfly-borne viral disease as far as case fatality is concerned. India experienced a massive outbreak of Chandipura encephalitis during 2003-2004, which killed more than 300 children in Maharashtra, Telangana and Gujarat3,4. The disease mainly affects children below the age of 15 yr and is characterized by high fever, convulsions and altered sensorium3-5. Death is generally occurs within 24-48 h of exhibition of symptoms. The precise mechanism of action of the virus could not be explained yet; however, recent studies have identified increased expression of viral phosphoprotein and rapid apoptosis of the neuronal cells6. Although the outbreak was contained, the region has become endemic for Chandipura encephalitis as sporadic cases with case fatalities are still reported4,5,7,8. Maharashtra and Telangana showed drastic decline since 2010-2011; however, several districts of Gujarat, viz. Vadodara, Panchmahal, Dahod, Kheda, Anand, Ahmedabad, etc., have recently been identified as hotspots for CHPV9. An outbreak in Odisha involving death of 10 tribal children and detection of CHPV IgM antibodies in AES patients in Odisha and Uttar Pradesh points towards the geographic expansion of CHPV10.

Sandflies belonging to genus Phlebotomus, especially Ph. papatasi, were incriminated as the vector of CHPV initially, due to its abundance in outbreak areas and its potential to transmit the virus both horizontally and vertically4,11. Recent studies, however, have shown CHPV activity in Sergentomyia species as observed by molecular detection and virus isolation7,9,12. In India, sandflies are mainly associated with cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis, which is a major problem in Bihar and West Bengal13,14. Leishmaniasis is a major health problem in tropical and subtropical countries with approximately five lakh visceral and 1.5 million cutaneous leishmaniasis cases with a death toll of approximately 60,000 per year15.

Vidarbha region of Maharashtra has become endemic for Chandipura encephalitis with recurring sporadic outbreaks with case fatalities since 20035,7,8. Incidentally, Chandipura is a small village in Nagpur district of Vidarbha region from where the virus was first isolated from two adult patients with febrile illness16. Earlier studies showed that this region had a high abundance of Phlebotomus sandflies, which was found throughout the year with varying densities according to seasons17. Sandfly studies conducted during an outbreak of CHPV in 2007 demonstrated abundance of Sergentomyia spp. of sandflies with an inversely proportional growth of Phlebotomus spp. in the area5. Subsequent studies yielded CHPV isolation from Sergentomyia sandflies in India7. The present study was therefore designed to determine the sandfly fauna of three districts of the region, viz. Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya, in the context of CHPV endemicity.

Material & Methods

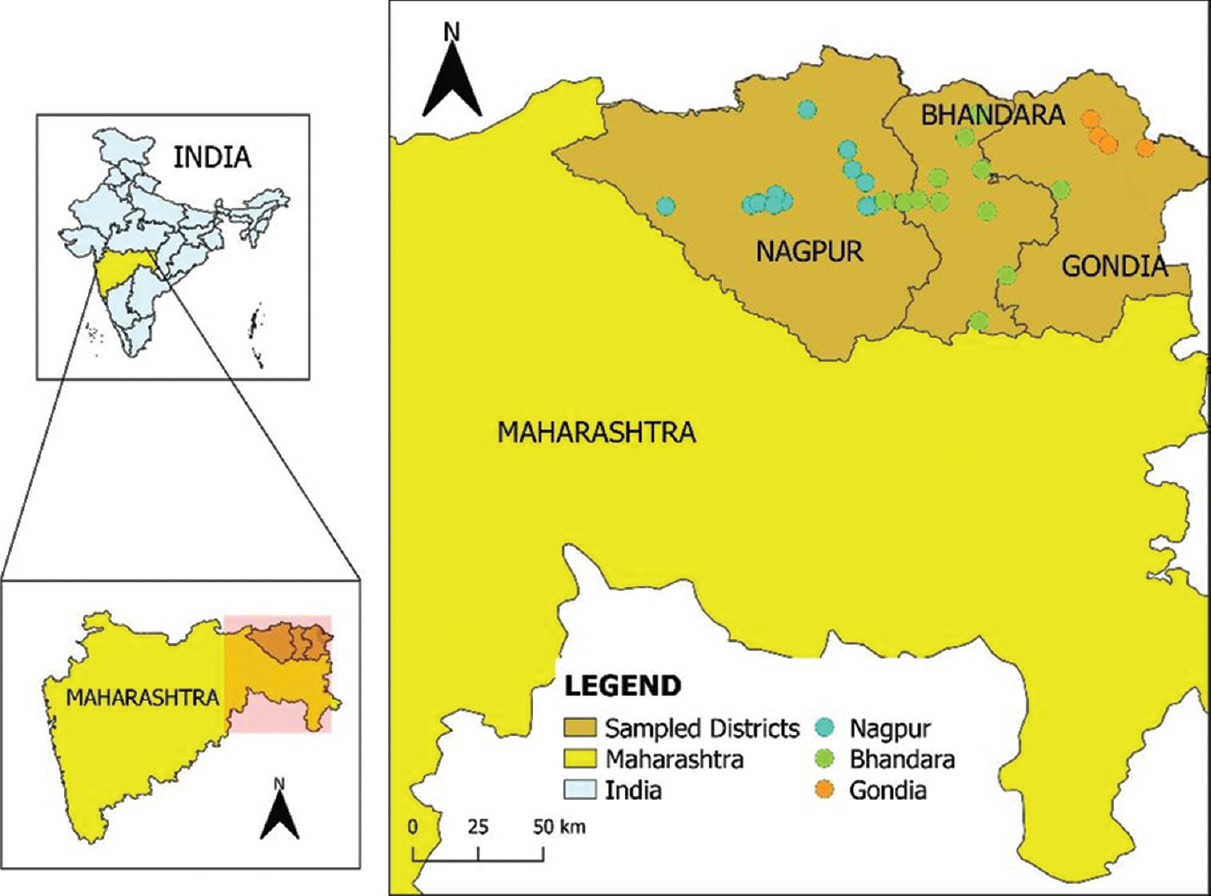

Description of the study area and period of collection: The study area comprised 23 villages and two urban sites spanned across three districts of Vidarbha region, viz. Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya between October 2018 and September 2019 (Fig. 1). The collection sites were selected based on documented history of Chandipura cases as well as reports of high prevalence of sandflies. Most of the villages selected were situated approximately 30-40 km away from the respective district headquarters. Although majority of the collection sites still retained traditional rural characteristics, a few had initiated of infrastructure developments such as construction of multi-storey buildings and commercial establishments.

- Study sites in Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya districts in Maharashtra (sites were selected according to Chandipura virus endemicity.

The three study-districts are located in the Vidarbha meteorological subdivision of India and have similar terrain and climatological features18. Located in the central part of the Deccan Plateau in peninsular India, these three districts are landlocked and experience very high temperatures (≥45°C) during the pre-monsoon season (March-May).

Sandfly collection: Adult sandfly collections were made from their resting places both indoors and outdoors using handheld mouth aspirators. Indoor collections were made from living rooms, toilets, bathrooms, store rooms, office rooms and school classrooms including anganwadis. Outdoor resting sites mainly consisted of tree holes, termite mounds and mud crevices. All the collections were made during daytime between 10.00 and 16.00 h. Multi-storey residential complexes were not included in the study. The collections were held in Barraud cages and brought live to the laboratory where they were identified using keys provided by Lewis19. They were then pooled according to species, gender and locality and stored at −80°C until processed for virus isolation. Head and genitalia of 10 per cent of the collections were preserved in Hoyer’s medium for future reference. The collection time was recorded and per man-hour density (PMHD) was calculated to determine the abundance of sandflies as described earlier17.

Virus isolation: Sandflies were processed for virus isolation using Vero E6 cells as described by Sudeep et al7. The cells were observed daily for cytopathic effect (CPE) and further processing was done on the appearance of CPE. All the samples were passaged at least twice before declaring them as negative.

Meteorological data: Meteorological data were recorded from WMO-recognized sources (www.timeanddate.com) and computed monthly and seasonal averages from daily reports. Average for the entire region was computed as the three districts belonged to the Vidarbha meteorological subdivision (like meteorological district) of India18. Four seasons are defined for Indian subcontinent, viz. winter (December-January-February: DJF), pre-monsoon (March-April-May: MAM), South-west monsoon (SW Monsoon: June-July-August-September: JJAS) and post-monsoon (October-November: ON). This classification was followed for our analyses.

Mathematical and statistical analyses: Mathematical calculations and statistical analyses were performed using MS Excel and R software version 4.3.0. For better estimation of the biodiversity of sandfly species (richness, diversity and evenness), we have calculated the diversity indices as described below.

Shannon–Wiener’s diversity index: Shannon–Weiner’s diversity index is based on the uncertainty that an individual taken randomly from a dataset is predicted as a certain species correctly. Bigger the value, bigger the uncertaintyand greater diversity of species. This is depicted as:

where pi = ni/N, pi = proportion of total sample represented by ith species and ni is the number of samples of the ith species, N is the total specimens collected (total collection) and S is the total number of species20,21.

Shannon evenness index (SEI): The Shannon–Wiener evenness is defined as:  where S is the total number of species in any geographical location (i.e., total number of sandfly species) and H’ is the Shannon–Wiener’s diversity index. Value of E lies between 0 and 1 and the value E=1 indicates complete evenness which signifies that all the species are equally abundant in the area. Evenness is the relative abundance of different species in a particular area22.

where S is the total number of species in any geographical location (i.e., total number of sandfly species) and H’ is the Shannon–Wiener’s diversity index. Value of E lies between 0 and 1 and the value E=1 indicates complete evenness which signifies that all the species are equally abundant in the area. Evenness is the relative abundance of different species in a particular area22.

Simpson’s index of diversity: Simpson’s index of diversity (1 − D) reflects the probability that two individuals taken at random from the dataset are not the same species (i.e., will belong to different species). It is defined as:

where ni is the number of the ith species and N is the total number of specimens in the studied location23.

Heydemann’s species dominance: Heydemann’s classification of species dominance was used to evaluate the dominance structure24,25. Five degrees of dominance have been identified, i.e., eudominant species (those making up >30 per cent of the total collection); dominant (10-30%), subdominant (5-10%), rare (1-5%) and sub-rare (<1%).

Results

Six thousand five hundred and sixty eight (6568) sandflies belonging to five species were collected from 25 sites in the Vidarbha region spanning 12 months during 2018-2019 (Table). Predominance of Sergentomyia species of sandflies was evident during the collections as they contributed to approximately 99 per cent of the samples. Sergentomyia babu was collected from all 25 study sites including the two urban sites demonstrating its wide prevalence in the study area contributing to 70.7 per cent of the total collection. Ser. punjabensis constituted 19.5 per cent of the total collection while Ser. bailyi contributed to 5.9 per cent of the total collection. Genus Phlebotomus was represented by only Ph. argentipes and Ph. papatasi. Populations of both the species have shown a sharp decline as both the species together constituted only 1.21 per cent of the total collection. Ph. argentipes (0.89%) was collected from cattle sheds in four villages, while Ph. papatasi (0.32%) could be collected from only one village in Bhandara district. A few specimens (2.7%) belonging to genus Sergentomyia could not be identified to the species level due to damage. The species distribution and abundance of each study site are given in Table.

| District | Name of village | Sandfly species distribution in different study sites (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phlebotomus papatasi | Phlebotomus argentipes | Sergentomyia babu | Sergentomyia bailyi | Sergentomyia punjabensis | ||

| Nagpur | Wad Dhamna | 0 | 0.67 | 3.3 | 0.62 | 1.81 |

| Wadi | 0 | 0 | 1.48 | 0.05 | 0.58 | |

| Navegaon | 0 | 0 | 12.67 | 1.36 | 2.83 | |

| Nagardhan | 0 | 0 | 8.68 | 0.9 | 3.78 | |

| Dudhada | 0 | 0.12 | 2.85 | 0.43 | 2.1 | |

| Chachar | 0 | 0 | 0.69 | 0.14 | 0.05 | |

| Tarsa | 0 | 0 | 1.51 | 0.37 | 0.23 | |

| Police line (U) | 0 | 0 | 0.21 | 0.2 | 0.05 | |

| ADHS campus (U) | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mauda | 0 | 0 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.32 | |

| Bhandara | Rangpeth | 0 | 0 | 0.32 | 0 | 0 |

| Chinchtola | 0 | 0.02 | 13.6 | 0.88 | 1.78 | |

| Varithi | 0 | 0 | 5.66 | 0.17 | 0.41 | |

| Kharbi | 0 | 0 | 6.79 | 0.6 | 1.36 | |

| Zonad | 0 | 0 | 0.72 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gopipada | 0 | 0 | 1.96 | 00 | 0.15 | |

| Mathani | 0 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.18 | |

| Narva | 0 | 0 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.08 | |

| Tumsar | 0 | 0 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | |

| Chulhad | 0.32 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.32 | |

| Kharadi | 0 | 0 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.3 | |

| Marudi | 0 | 0 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.32 | |

| Gondiya | Patampur | 0 | 0 | 0.91 | 0 | 0.27 |

| Wagh Tola | 0 | 0 | 1.61 | 0.12 | 0.11 | |

| Nandora Tola | 0 | 0 | 0.67 | 0 | 0.67 | |

As per the Heydemann’s principles of species dominance24, Ser. babu is the eudominant species as they were most predominant (>30%) in the area. Ser. punjabensis becomes the dominant species as its proportion ranged between 10 and 30 per cent of the total collection. Ser. bailyi was termed as the subdominant species as it contributed to approximately 10 per cent of the collection. Since Ph. argentipes and Ph. papatasi constituted <5 per cent of the total collection, they were termed as rare species. Overall, considering the year-round data, the Shannon-Wiener’s diversity index was found to be H=0.713 and Shannon evenness E=0.443. This signified that all the species were not equally distributed in the study area. The Simpson’s index of diversity was found to be (1−D) = 0.432, which signified that there existed a probability that any two samples selected at random would not be the same species. This meant that diversity existed in the study area.

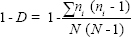

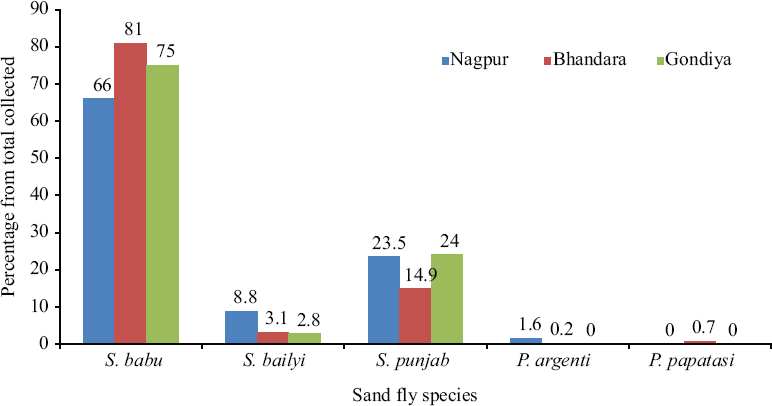

District-wise species distribution: District-wise species distribution showed predominance of Ser. babu in the three districts (Fig. 2). In Nagpur district, Ser. babu represented 66 per cent, whereas Ser. punjabensis and Ser. bailyi constituted 23.5 per cent and 8.8 per cent of the total collection, respectively. In Bhandara district, the percentages of Ser. babu, Ser. punjabensis and Ser. bailyi were 81, 14.9 and 3.1 per cent of the total collection, respectively. Similarly, the three species in Gondiya district constituted 75, 2.8 and 22.2 per cent of the collection respectively. Male:female ratio of Ser. babu was almost equal in all the three districts represented by 54:46, 57:43 and 55:45, respectively (Fig. 3). However, the male–female ratio in Ser. bailyi showed greater proportion of females in Bhandara and Gondiya districts with 38:62 and 38:62, respectively, while in Nagpur it was almost equal (53:47). In the case of Ser. punjabensis, male–female ratio was found male dominated with 68:32, 73:27 and 65:35 for Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya districts, respectively (Fig. 3). Phlebotomus argentipes population in Nagpur and Bhandara districts individually represented with 1.6 and 0.2 per cent, respectively, while Ph. papatasi was collected from only Bhandara district and represented with 0.7 per cent of the sandfly collection from the district.

- Species distribution of sandflies in Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya districts.

- Male–female ratio of three species of Sergentomyia sandflies collected from Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya districts of Maharashtra.

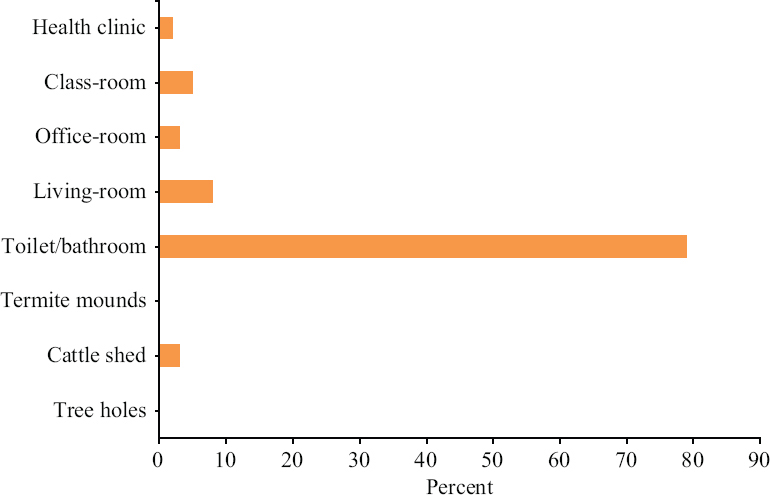

Breeding habitats: A shift in the breeding/resting habitats of Sergentomyia species was observed throughout the study. Sergentomyia spp. of sandflies, a peri-domestic breeder (outdoor breeding sandfly), was found mainly breeding/resting indoors as 96.4 per cent were collected from indoor resting areas, i.e. bathrooms, toilets, living rooms, classrooms, office rooms, etc. (Fig. 4). Stray collections were made from tree holes, termite mounds and mud crevices with very low productivity. Cattle sheds, considered as major breeding sites for sandflies, were also found less productive as only a few Ph. argentipes and Sergentomyia spp. could be collected.

- Breeding/resting sites of sandflies in Nagpur, Bhandara and Gondiya districts.

Abundance and seasonal prevalence:

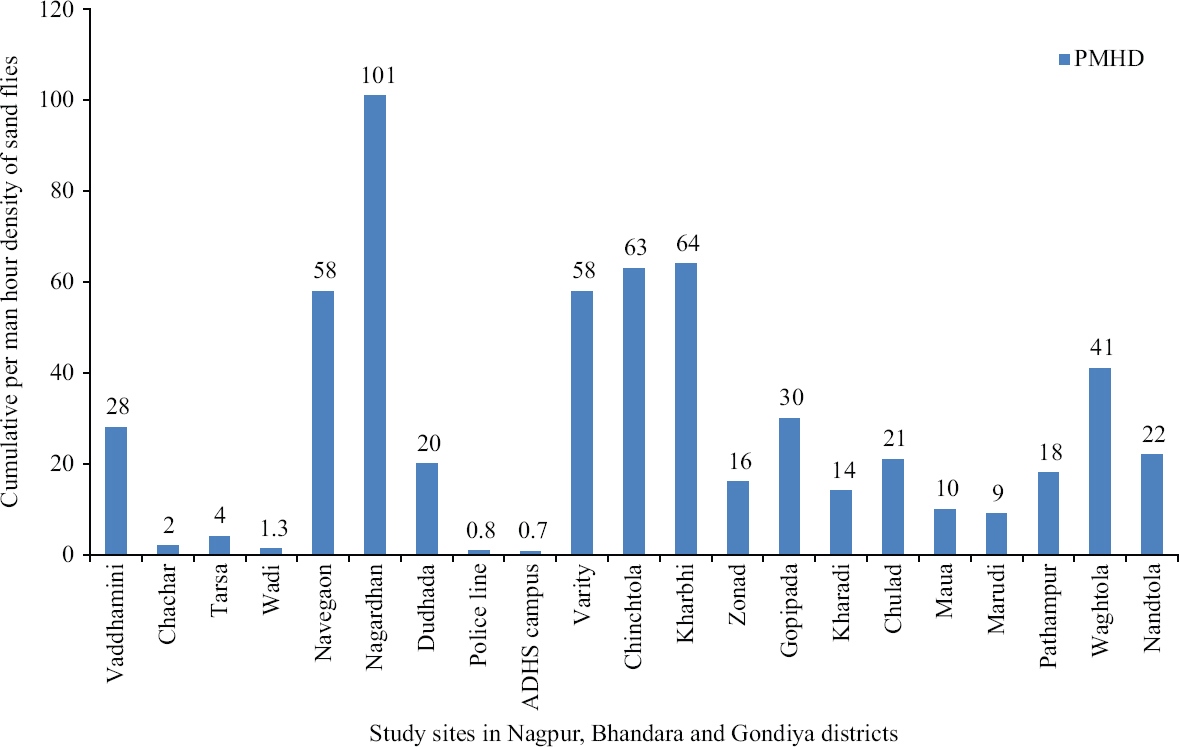

Abundance: Sandfly abundance was estimated in terms of per man hour density (PMHD). Of the 25 locations, several locations were visited for more than once, and hence, a cumulative PMHD was calculated to determine the abundance or density of sandflies at a particular site. Average PMHD was determined by dividing the total number of sandflies collected from all the sites during the entire course of the study with total man-hour spent and it was found to be 35. The PMHD for the urban areas, which included Additional Director of Health services (ADHS) Office campus, police line and Wadi township within Nagpur municipal limits, was found comparatively low (<1), while in rest of the study sites, PMHD was found in the range of 1.5 to 101. Sandfly densit in remote villages with typical rural characteristics was high and PMHD was in the range of 32 to 101. Navegaon and Nagardhan villages in Nagpur district and Chinchtola, Varity and Kharbi villages in Bhandara district had the highest sandfly density (Fig. 5).

- Cumulative per man-hour density of sandflies in selected study areas (sites) in Vidarbha region.

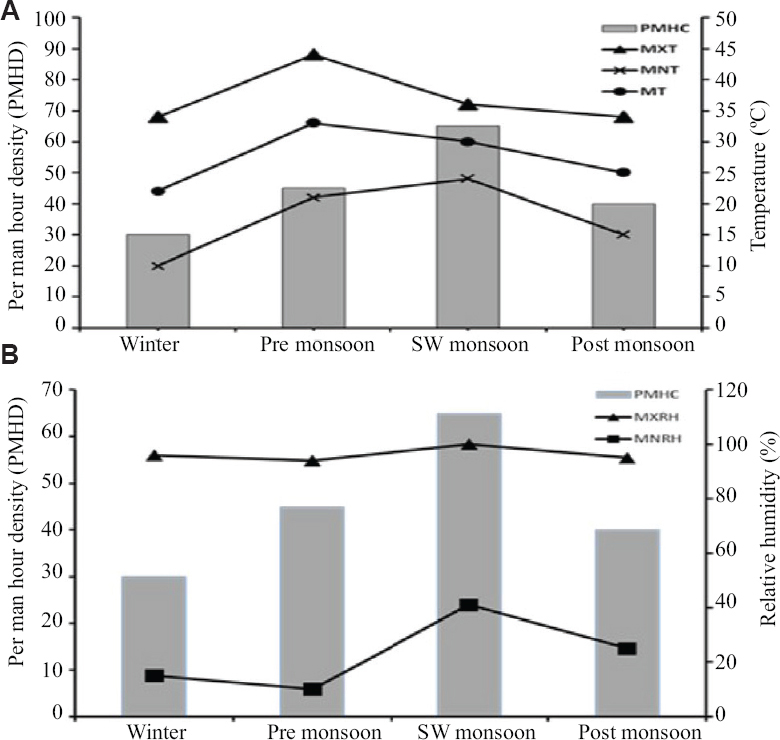

Seasonal prevalence and influence of meteorological parameters: Collections were made throughout the year covering all the four seasons, i.e. winter, pre-monsoon, monsoon and post-monsoon, and sandfly abundance was estimated in terms of PMHD. Figure 6 shows the seasonal variability and abundance of sandflies in relation to influence of meteorological parameters. The highest abundance in terms of PMHD was observed in monsoon season while the lowest was seen in winter. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was determined as a measure of association between the meteorological parameters and sandfly abundance. Strong positive associations were observed between sandfly abundance and temperature [mean temperature (MT), r=0.66; and minimum temperature (MNT), r=0.93]. Similarly, strong positive association was also observed between sandfly abundance with (i) maximum relative humidity, r=0.73, and (ii) minimum relative humidity (MNRH), r=0.78. This signified that both temperature and humidity had positive influence on sandfly abundance, i.e. 25-28oC was found ideal for sandfly breeding. Similarly, relative humidity played an important role in sandfly abundance and showed an increase in the number of sandflies during post-monsoon season.

- Seasonal prevalence of sandflies in three districts of Maharashtra (as per per man-hour density) in correlation to (A) temperature and (B) relative humidity.

Discussion

Vidarbha region of Maharashtra had a rich fauna of sandflies belonging to genus Phlebotomus and was found abundant throughout the year17,25. However, in the present study, sandfly population did not show high diversity in terms of species as only five species under two genera (Sergentomyia and Phlebotomus) could be collected. Simpson’s index of diversity was used to measure the heterogeneity of sandfly demographics in the study area and we found a moderate level of diversity of sandfly species. The Shannon–Weiner’s diversity index indicated richness of sandfly species and the index of Evenness was found to be moderate at 0.443 but indicated that all species were not equally abundant in the area.

The present study also revealed the predominance of Sergentomyia species over genus Phlebotomus. These findings are in sharp contrast with earlier study results conducted during late 1970s when nearly 70 per cent of the collection was constituted by Ph. papatasi17. During the present study, Ph. papatasi could not be collected from any of the 10 study sites in Nagpur district and the only collection was made from Chulhad village in Bhandara district (n=21), which is located 110 km away from Bhandara district headquarters. The collection was made from a cattle shed in a mixed dwelling setup. This observation is in agreement with earlier studies by Modi et al17 as they recorded collections from human dwellings, cattle sheds, mixed dwellings and even from termite mounds, tree holes, etc., from the region. Earlier studies by Kumar et al26 also recorded Ph. papatasi sandflies from Katurli village in Bhandara district suggestive of its prevalence in the district.

Ph. argentipes showed drastic reduction both in its abundance and prevalence compared to earlier surveys (1970s). It was restricted to only four villages: two in Nagpur and two in Bhandara districts yielding a meagre 0.89 per cent of the total collection. On the contrary, Sergentomyia spp. showed a surge in their population and constituted ~99 per cent of the total collection. As per the Heydemann’s species dominance principles, Ser. babu was estimated to be the eudominant species, which had a wide prevalence in three districts. Ser. punjabensis was found to be the dominant species (10-30%) and Ser. bailyi as the subdominant species (<10%). Modi et al17 had described the prevalence of five Sergentomyia species in the area during 1970s but in negligible populations and were found mainly breeding outdoors, viz. tree holes, rodent burrows, etc. In the present study, we could not collect Ser. clydei and Ser. squamipluris, two species reported earlier from the area. It is very difficult to draw an inference on the decline in the population of Ph. papatasi and Ph. argentipes as most of these villages still maintained typical rural characteristics and practice agriculture. Probably, it could be attributed to excessive use of insecticides as this area is endemic to malaria and acute encephalitic syndrome7. Environmental changes, especially increase in temperature over the years, could also be a probable reason for the decline in the population of these species. This has similarity to studies conducted in the Pune district of Maharashtra by Geevarghese et al27 where they showed drastic reduction in sandfly abundance as well as the number of species as compared to collections made during 1969-1970. They attributed rapid urbanization of Pune city and climate change as such a probable reasons for the decline in sandfly population.

The influence of meteorological factors on seasonal variability in sandfly abundance was observed during the study. The highest abundance was observed during the monsoon and post-monsoon season while the least was observed in winter. The influence of meteorological parameters on sandfly abundance was also evaluated in terms of time series analyses and Pearson’s correlation coefficient and we found that the overall sandfly abundance was modulated by temperature (positive association with MNT and MT) and humidity.

One of the major setbacks of the present investigation was the inability to isolate CHPV despite processing >6500 sandflies. In our earlier studies, we isolated CHPV from two Sergentomyia sandflies collected from Chacher village in Nagpur7. The absence of virus detection in the vector could probably be attributed to possible absence of active circulation of CHPV within its ecological niche. It is generally believed that active virus circulation within the natural reservoir hosts and the vectors precedes incidence of human cases. The near absence of CHPV incidence amongst humans during the study period and the absence of virus detections in the vectors suggest the lack of CHPV circulation in the area. It is well documented that CHPV remains dormant for a long period in nature probably in Phlebotomus sandflies as they maintain the virus through transovarial and venereal transmission and transmit to humans during favourable conditions3,17.

No experimental studies with CHPV in Sergentomyia species have been reported so far, which could be due to their zoophilic nature. However, recent studies have shown anthropophilic nature of at least some species as Leishmania major DNA and several viruses of human origin were detected in them28,29. Detection/isolation of CHPV in Sergentomyia spp. also points towards its anthropophilic nature as no natural reservoir apart from humans is known7,9. Apart from CHPV, Toscana virus, Saboya virus, sandfly Sicilian-like virus, Tete virus and several unidentified viruses have been detected/ isolated from the members of genus Sergentomyia recently in the Middle East and the Mediterranean Basin30,31. Toscana virus is a known human pathogen with the potential to cause meningitis and encephalitis.

In conclusion, the skewed representation of Phlebotomus genus and the surge of Sergentomyia genus warrant an urgent need for evaluation. Studies related to bionomics of arboviral vectors emphasize the four pillars, viz. repeated isolations, virus replication in the vector, anthropophily and seasonal correlations. However, the potential of Sergentomyia group of sandflies to harbour CHPV, Toscana and other viruses of public health importance poses a major concern, especially when they have adapted to breed/rest in places close to humans.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Arthropod-borne viruses transmitted by Phlebotomine sandflies in Europe: A review. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phlebotomine sand fly-borne pathogens in the Mediterranean Basin: Human leishmaniasis and Phlebovirus infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005660.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura encephalitis: A newly recognized disease of public health importance in India. Emerging infections 2007:121-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing clinical scenario in Chandipura virus infection. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143:712-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura virus encephalitis outbreak among children in Nagpur division, Maharashtra, 2007. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:395-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura virus induces neuronal death through Fas-mediated extrinsic apoptotic pathway. J Virol. 2013;87:12398-406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of Chandipura virus (Vesiculovirus:Rhabdoviridae) from Sergentomyia species of sandflies from Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:769-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura virus: A major cause of acute encephalitis in children in North Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, India. J Med Virol. 2008;80:118-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular evidence of Chandipura virus from Sergentomyia species of sandflies in Gujarat, India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2018;71:247-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura virus infection causing encephalitis in a tribal population of Odisha in eastern India. Natl Med J India. 2015;28:185-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Growth and transovarial transmission of Chandipura virus (Rhabdoviridae:Vesiculovirus) in Phlebotomus papatasi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1983;32:621-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Chandipura virus from sand flies in the genus Sergentomyia (Diptera:Phlebotomidae) at Karimnagar District, Andhra Pradesh, India. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:495-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sandfly species diversity in association with human activities in the Kani tribe settlements of the Western Ghats, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2015;110:174-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular taxonomy of the two Leishmania vectors Lutzomyia umbratilis and Lutzomyia anduzei (Diptera:Psychodidae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chandipura: A new Arbovirus isolated in India from patients with febrile illness. Indian J Med Res. 1967;55:1295-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution and adult habitats of phlebotomid sandflies (Diptera:Phlebotomidae) from Maharashtra State. Indian J Med Res. 1978;68:747-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meteorological parameters and seasonal variability of mosquito population in Pune Urban Zone, India: A year-round study, 2017. J Mosq Res. 2018;8:18-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) of the Oriental Region. Bull Br Museum (Nat Hist) Entomol. 1978;37:1-343.

- [Google Scholar]

- A consistent terminology for quantifying species diversity?Yes, it does exist. Oecologia. 2010;164:853-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Species evenness and productivity in experimental plant communities. Oikos. 2004;107:50-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the 'Shannon–Wiener'Index. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2013;12:177-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the sandflies collected indoors in Aurangabad district Maharashtra state (Diptera:Psychodidae) Indian J Med Res. 1971;59:1565-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- DNA barcoding for identification of sand flies (Diptera:Psychodidae) in India. Mol Ecol Resour. 2012;12:414-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of environmental changes on the prevalence of sand flies in Pune and its suburbs. Bionotes. 2002;4:31-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- First detection of Leishmania major DNA in Sergentomyia (Spelaeomyia) darlingi from cutaneous leishmaniasis foci in Mali. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28266.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sergentomyia schwetzi is not a competent vector for Leishmania donovani and other Leishmania species pathogenic to humans. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:186.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toscana virus RNA in Sergentomyia minuta files. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1299-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and sequencing of Dashli virus, a novel Sicilian-like virus in sandflies from Iran;genetic and phylogenetic evidence for the creation of one novel species within the Phlebovirus genus in the Phenuiviridae family. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005978.

- [Google Scholar]