Translate this page into:

Delirium in the elderly: current problems with increasing geriatric age

Reprint requests: Dr Julius Popp, Department of Psychiatry, Division of Old Age Psychiatry, University Hospital of Lausanne, Switzerland Site de Cery, 1008 Lausanne, Switzerland e-mail: Julius.Popp@chuv.ch

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Delirium is an acute disorder of attention and cognition seen relatively commonly in people aged 65 yr or older. The prevalence is estimated to be between 11 and 42 per cent for elderly patients on medical wards. The prevalence is also high in nursing homes and long term care (LTC) facilities. The consequences of delirium could be significant such as an increase in mortality in the hospital, long-term cognitive decline, loss of autonomy and increased risk to be institutionalized. Despite being a common condition, it remains under-recognised, poorly understood and not adequately managed. Advanced age and dementia are the most important risk factors. Pain, dehydration, infections, stroke and metabolic disturbances, and surgery are the most common triggering factors. Delirium is preventable in a large proportion of cases and therefore, it is also important from a public health perspective for interventions to reduce further complications and the substantial costs associated with these. Since the aetiology is, in most cases, multfactorial, it is important to consider a multi-component approach to management, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological. Detection and treatment of triggering causes must have high priority in case of delirium. The aim of this review is to highlight the importance of delirium in the elderly population, given the increasing numbers of ageing people as well as increasing geriatric age.

Keywords

Delirium

elderly

management

prevalence

prevention

risk factors

What is delirium?

Delirium is an acute disorder of attention (reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain and shift attention) and awareness (reduced orientation to the environment) seen relatively commonly in elderly people (i.e. those aged 65 yr or older). The disturbance usually develops over a short period of time (hours to a few days), and tends to fluctuate in severity during the course of a day. An additional disturbance in cognition (e.g. memory deficit, disorientation, language, visuospatial ability, or perception) may also occur. There may also be disturbances in psychomotor behaviour, emotion and sleep-wake cycle1.

Although a single event can precipitate delirium, it is more common for multiple factors to interact and a multifactorial model of delirium has been established to help illustrate how delirium is precipitated in people at risk2. It can be a common and distressing complication of a range of stressor events including infection, metabolic disturbances, new medications and environment change that is often experienced by older people with frailty and dementia. Brain injury concurrent with an abnormal stress response may also contribute to the development of delirium. Diagnosing delirium is complicated because many critically ill or cognitively impaired older adults cannot communicate their needs effectively.

Very few studies from India have studied the phenomenology of delirium in the elderly, and have shown relatively high incidence and prevalence rates, 25 and 54 per cent, respectively34. A recent nationwide web-based survey conducted across hospitals in India has shown that delirium remains an under-recognized entity5. Khurana et al6 showed that the mortality rate with delirium was 14.75 per cent and that there was a high prevalence of hypoactive delirium (65%) as compared to hyperactive (25%) or mixed (10%).The most common aetiology was sepsis followed by metabolic abnormalities.

Clinical features

The clinical picture of delirium is characterized by clouding of consciousness accompanied by global cognitive and behavioural changes. Four core features define delirium at present: a disturbance of consciousness, a disturbance of cognition, limited course and external causation. There is a diurnal fluctuation in the confusion state marked by disturbance of awareness, attention and other cognitive functions, psychomotor behaviour, emotion, as well as the sleep-wake cycle. Delirium often lasts for a few hours or days; however, if not detected and adequately treated, it may persist for weeks or months.

According to the nature of changes in motor behaviour, delirium is divided into hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed subtypes. Despite precautions, delirium is unavoidable in some cases and clinicians should be familiar with the typical features and varied presentations of this condition. A careful history and examination with appropriate investigation allows detection and treatment of the underlying causes. Since delirium is almost always triggered by a medical condition, there must be an aggressive search for the causative insult(s) so that a targeted intervention can be started promptly.

Why is delirium in the elderly important?

The geriatric age group is the fastest increasing age group worldwide. Accelerated population ageing experienced in the last few decades is an unprecedented phenomenon. Currently, this is the case in particular in the developing countries. Soon three-fourths of the elderly population will live in the developing world. The life span in India has increased from 32 years in 1947 to more than 62 years now7. It is expected to reach 70 years by 2030. From the morbidity point of view, almost 50 per cent of the Indian elderly have chronic diseases and five per cent suffer from immobility. The elderly population is the most vulnerable group for delirium8.

Delirium is a common clinical condition in the elderly, especially in those who are hospitalized and/or severely compromised medico-surgical subjects. It complicates/prolongs medical condition/hospitalization, and may lead to chronic disability and even death9. It also has substantial health and socio-economic costs1011.

The prevalence of delirium in elderly persons living in the community overall is low (1-2%) but increases with age, rising to 14 per cent among individuals older than 85 yr. The prevalence is 10-30 per cent in older individuals presenting to emergency departments, where the delirium often indicates a medical illness4. The prevalence of delirium is highest among hospitalized older individuals and varies depending on the individuals’ characteristics, setting of care, and sensitivity of the detection method. A study by Sharma et al4 addressing the incidence, prevalence and outcome of delirium in the intensive care unit (ICU), showed that a significantly higher percentage of elderly patients developed delirium compared to younger patients and this finding supports the notion that prevalence and incidence of delirium is much higher in the elderly and that older age is one of the most important predisposing risk factor for delirium.

The prevalence of delirium when individuals are admitted to the hospital ranges from14 to 24 per cent, and estimates of the incidence of delirium arising during hospitalization range from 6 to 56 per cent in general hospital populations. Delirium occurs in 15-53 per cent of older individuals postoperatively and in 70-87 per cent of those in intensive care. Delirium occurs in up to 60 per cent of individuals in nursing homes or post-acute care settings and in up to 83 per cent of all individuals at the end of life69.Delirium is highly prevalent in the cardiac ICU setting and is associated with presence of many modifiable risk factors. Development of delirium increases the mortality risk and is associated with longer cardiac ICU stay12. However, one of the important limitations of studies evaluating incidence and prevalence rates of delirium in the ICU is that the diagnosis is often based exclusively on screening instruments1314, and in only a few studies was the diagnosis of delirium confirmed by a psychiatrist151617.

Short-term consequences: People with delirium usually become more confused over a few hours or a couple of days. Some people with delirium become quiet and sleepy but others become agitated and disorientated, so it can be a very distressing condition, both for the patient as well as the caregivers. These patients can have severe attention deficits, perceptual disturbances, language disturbances, agitation, sleep-wake cycle alterations and significant motor activity changes, which can be difficult to manage9. Delirium in older adults in critical care is associated with poor short-term outcomes, including longer hospital stays, greater use of continuous sedation and physical restraints, increased unintended removal of catheters, self-extubation, higher rates of complications, and increased mortality.

Long-term consequences: There is now evidence that delirium may also have severe long term sequelae, especially in elderly patients. In particular, delirium after remission remains associated with increased risk of functional decline, cognitive dysfunction, and institutional placement, and with higher mortality. Hospitalized individuals 65 yr or older with delirium have three times the risk of nursing home placement and about three times the functional decline as hospitalized patients without delirium at both discharge and three months post-discharge141819. Delirium in many

older hospitalized adults appears to be much more protracted than previously thought, especially in those with dementia, although delirium symptoms, cognition, and function may improve with partial and no recovery20. Older people living in institutional long term care (LTC) are at high risk of delirium, which increases the risk of admission to hospital, development of or worsening of dementia, and mortality. Delirium is associated with increased long term morbidity, functional decline, risk of developing or worsening dementia and death1018. Delirium is also associated with substantial healthcare costs2122.

What are the causes of delirium?

Delirium is triggered when a susceptible individual is exposed to often multiple precipitating factors, including infection, medications, pain and dehydration23. Both susceptibility and precipitating factors are considered to interact in a cumulative manner; the greater the number and severity of factors, the greater the risk of delirium (Table). Many of these factors are modifiable, and care must be taken to identify and treat these factors, to prevent and treat delirium effectively. Complex interrelationships exist between predisposing and precipitating factors of delirium. Development of delirium requires a severe acute medical condition such as sepsis or another strong precipitant in patients with low vulnerability. However, in patients with high vulnerability, even a rather mild stimulus can lead to delirium or prolong its duration. Furthermore, the pathophysiological changes associated with delirium may add to the pre-existing cerebral disease and accelerate the progression of neurodegenerative processes25. Several pathophysiologic pathways including inflammation, cerebral hypoperfusion, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal axis hyperresponsiveness, and others seem to be involved in the genesis of delirium and may contribute to its long-term sequelae26. While the precise mechanisms remain still incompletely understood, there is evidence that a disturbed interaction between various neurotransmitters including acetylcholine, dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate and gamma-amino hydroxybutyric acid (GABA) underlies the symptoms of delirium27.

There are many possible risk and precipitating factors for delirium that need to be kept in mind, evaluated, and, if possible, treated in any individual patient. The predisposing factors include older age; major and mild neurocognitive disorders (dementia and mild cognitive impairment); visual and/or hearing impairment; poorer functional ability; male gender; co-morbid illnesses such as hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, anaemia, malignancy and past psychiatric illness; severity of illness; history of falls; immobility; alcohol abuse; and long-term use of medications (prescribed or non-prescribed).

The precipitating factors are malnutrition; any iatrogenic event during hospitalization; physical restraints or bladder catheter; more than three newly prescribed medications; high number of procedures during early hospitalization (X-rays, blood tests, etc.); intensive care treatment; mechanical ventilation; prolonged waiting time before surgery; type and duration of operation; intra-operative blood loss; postoperative pain and problems in pain management; infection; and use of drugs with a high anticholinergic activity, opiates, benzodiazepines and corticosteroids.

A study from India4 has shown that the predisposing risk factors identified for delirium in intensive care patients were higher age; higher Glasgow Coma Scale score; increased APACHE II score; hyperuricemia; hypoalbuminaemia; presence of acidosis; abnormal alkaline transferase levels; use of mechanical ventilation; higher number of total medication received and use of sedative, steroids and insulin. Age, multiple organ failure, hypoactive delirium and higher Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 (DRS-R-98) (delirium severity) scores were shown to be significant risk factors for mortality in patients with delirium. Khurana et al6 showed that sepsis and metabolic abnormalities were the most common aetiologies of delirium in the hospitalized elderly in medicine wards. The maximum patients had more than one aetiology and this emphasizes the multifactorial nature of delirium and need for thorough evaluation to unravel these. Most of the causes were treatable and had a favourable outcome (83% recovered). Guenther et al28 showed that in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery higher age, higher Charlson's comorbidity index, impaired cognition (lower MMSE) and length of cardiopulmonary bypass were important risk factors for the development of postoperative delirium. A study by Radtke et al29 showed that intraoperative monitoring of the depth of anaesthesia was associated with a lower incidence of delirium, possibly by reducing extreme low BIS (Bispectral index) values. Therefore, in high-risk surgical patients, the anaesthesiologist has the possibility to influence at least one precipitating factor in the complex genesis of delirium.

Risk assessment

Individual risk assessment can be performed on the basis of known risk factors for delirium. For example, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium propose risk estimation based on the clinical variables age above 65 yr, current hip fracture, cognitive impairment, and severe illness30. Different prediction rules have been validated in selected populations of patients undergoing cardiac surgery31, vascular surgery32, or hip fracture repair33, and may be included in the clinical routine, for example, as a part of the preoperative visit.

How to diagnose delirium?

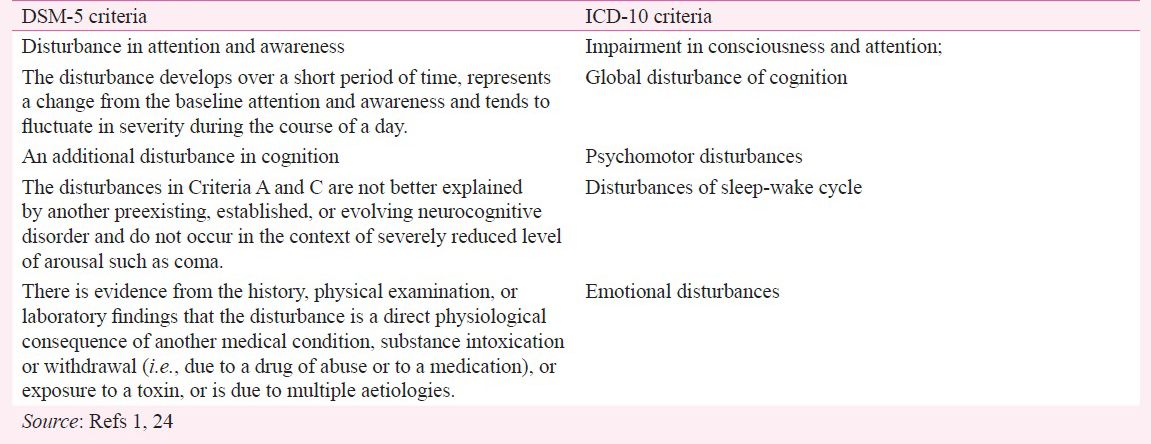

Diagnosis of delirium should be made by an experienced clinician and can be based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) criteria or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria124. Given the high incidence and prevalence of delirium in older patients, simple screening tools may be used by schooled staff members such as nurses to identify cases of possible delirium which may be subsequently verified by a psychiatrist.Special scales, such as Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU)3435, Nursing Delirium Screening Scale, DRS-R-98, the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) and Single Question in Delirium can be used to identify delirium. There are also other scales such as the Revised Delirium Rating Scale and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale which are the best available options for monitoring severity, and the Cognitive Test for Delirium provides detailed neuropsychological assessment for research purposes3637.

Can we prevent delirium?

While it is currently unclear whether interventions to prevent delirium in LTC are effective, multi-component delirium prevention programmes proved to reduce the incidence of delirium in different hospital settings. Preventive measures should be implemented in high risk patients, such as those with malnutrition, polypharmacy, infections, previous delirium, or dementia. Several delirium prevention programmes have been developed using pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches38. Studies of people in hospital have shown that it is possible to prevent around a third of cases of delirium by providing an environment and care plan that target the main risk factors for delirium39. These prevention programmes are also applicable in nursing home settings, including in elderly people with dementia. For example, the NICE recommendations for prevention of delirium include an individually tailored multi-component intervention package to be delivered by a multidisciplinary team for assessment and treatment of cognitive impairment or disorientation, and physical complaints such as dehydration or constipation, poor nutrition, hypoxia, immobility or limited mobility, infection, multiple medications, pain, sensory impairment, and sleep disturbance30. The most recent NICE Quality standard on delirium may help to implement such programmes in different hospital and long-term care units40.

The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is a targeted multi-component strategy that has proven effective and cost-effective at preventing delirium and functional and cognitive decline in hospitalized older persons38. A recent study41 describes the systematic development of three new protocols (hypoxia, infection, pain) and the expansion of an existing HELP protocol (constipation and dehydration) to achieve alignment between the HELP protocols and NICE guidelines.

The overarching goals of HELP are to reduce delirium risk and maintain physical and cognitive function throughout hospitalization, maximize independence at discharge, assist with the transition from hospital to home, and prevent unplanned re-admission. The programme provides skilled interdisciplinary staff and trained volunteers to implement intervention protocols targeted toward six evidence-based delirium risk factors: orientation, oral volume repletion, early mobilization, therapeutic activities, vision and hearing optimization, and sleep enhancement. All patients are screened for eligibility for any of the underlying conditions that are part of the HELP protocol, and tailor-made interventions are assigned according to the risk factors. Once interventions are assigned, adherence is tracked daily, and quality assurance measures are incorporated at each step of the programme.

Interventions could include (i) avoiding moving people within and between wards or rooms unless absolutely necessary; (ii) ensuring that the person is cared for by a team of healthcare professionals who are familiar to them; (iii) providing appropriate lighting and clear signage; for example, a 24-h clock, a calendar; (iv) talking to the persons to reorientate them; (v) introducing cognitively stimulating activities; (vi) if possible, encouraging regular visits from family and friends; (vii) ensuring that the person has adequate fluid intake; (viii) looking for and treating infections; (ix) avoiding unnecessary catheterization; (x) encouraging the person to walk or, if this is not possible, to carry out active range-of-motion; (xi) exercises; (xii) reviewing pain management; (xiii) carrying out a medication review; (xiv) ensuring that the person's dentures fit properly; (xv) ensuring that any hearing and visual aids are working and are used; (xvi) reducing noise during sleep periods; and (xvii) avoiding medical or nursing interventions during sleep periods. Such prevention programmes have been estimated to be cost-efficient and result in savings for the public health systems42.

How to manage delirium?

Treatment of delirium should focus on identifying and managing the causative medical conditions, providing supportive care, and preventing and treating complications. The first important step in the treatment of delirium is the identification and management of individual precipitating factors, for example, medication, sensory deprivation, pain, infections, and sleep disturbance. Generally, non-pharmacological options are preferred over pharmacological treatment and should always be considered first4344. Pharmacologic interventions should be reserved for patients who are a threat to their own safety or the safety of others and those patients nearing death45. The use of antipsychotic drugs may contribute to prolong delirium duration and has been also found to accelerate cognitive and functional decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease46. Considering the risk of adverse side effects including sedation, prolonged delirium, prolonged immobilization, falls, and aspiration, pharmacological agents should be used for postoperative delirium only when non-pharmacologic measures prove ineffective. Also, pharmacological treatment should be restricted to patients who are distressed, in danger of harming themselves or others, or to make possible urgent diagnostic and therapeutic interventions4748. Despite the fact that there is neither any medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of delirium nor any robust evidence supporting the long term benefit of medications, there is general consensus that drug intervention can be attempted when non-pharmacological interventions are inappropriate or have failed.

In addition to reviewing the patient's current medications for any agents that may precipitate or contribute to delirium, a symptomatic pharmacological treatment may be necessary to reduce agitation, hyperactivity, and inappropriate behaviour. Short-term (usually for 1 week or less) use of appropriate antipsychotic medication, starting at the lowest clinically appropriate dose and titrating cautiously according to symptoms, should be considered for adults with delirium who are distressed or considered a risk to themselves or others when de-escalation techniques have been ineffective or are inappropriate40. Low-dose neuroleptics, haloperidol in particular, is recommended to correct behavioural changes495051. This may be administered orally, intramuscularly or intravenously. Second-generation antipsychotics, such as olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone have also been tried, but there is not sufficient evidence to show that these drugs reduce the severity and duration of delirium5052. It is noteworthy that there is no evidence that any drug treatment could be of benefit in alleviating the symptoms of delirium.

Future trends

Delirium is common, morbid, and costly for patients and health care systems. It is especially common in the elderly and is associated with significant increases in the length of hospital stay, requirement for institutional care, functional decline, and rate of death and healthcare costs, all of which become very important in a resource-scarce country with growing aged population like India. Hence, it is important for all clinicians (physicians and psychiatrists alike) to be aware of this entity and have basic knowledge to manage it. With as high prevalence as 42 per cent in the elderly in medical wards, significant functional decline and serious short and long term consequences, it would be necessary to focus more research, training and resources on this. Given that in many cases it is preventable and potentially reversible, it makes this all the more important.

To be able to identify and manage delirium effectively, hospital systems to address delirium should consist of three critical steps. First, it is necessary to identify patients who develop or are at intermediate or high risk for delirium. Delirium risk may be assessed using known patient-based and illness-based risk factors, including pre-existing cognitive impairment. Delirium diagnosis remains a clinical diagnosis that requires a clinical assessment that can be structured using diagnostic criteria and screening tools.

Second, it is crucial to develop a systematic approach to prevent delirium using multimodal non-pharmacologic delirium prevention methods and to monitor all high-risk patients for its occurrence. Tools such as the CAM, Nursing Delirium Screening scale and Sedation Scale, CAM-ICU can aid in monitoring for changes in mental status that could indicate the development of delirium.

Third, medical practitioners should use established methods to manage delirium in a systematic fashion. The key lies in addressing the underlying cause/causes of delirium, which often involves medical conditions or medications. With a sustained commitment, standardized efforts to identify, prevent, and treat delirium can mitigate the long-term morbidity associated with this acute change. In the face of changes in health care funding, delirium serves as an example of a syndrome where care coordination can improve short-term and long-term costs. For the family and health care staff, clear communication, education, and emotional support are vital components to assist with informed decision making and directing the treatment care plan. The family members are usually the primary care providers, and involving them in decision making and care of the patient can prove efficient and cost-effective.

Current advances in the field show improved knowledge about the predisposing and precipitating factors of delirium in the elderly, the need to assess risk, and the efficacy of using multi-component prevention programmes along with non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment approaches. However, there are still only limited studies on the incidence, the risk factors and the outcomes in patients with delirium from India. Older studies have included it under the heading of organic psychosis and showed it to be the most common diagnostic entity in consultation liaison psychiatric clinics. However, more recent studies show that delirium is highly prevalent in the ICU setting and is associated with presence of many modifiable risk factors and the development of delirium increases the mortality risk and is associated with longer ICU stay.

With the lack of systemic research from developing countries including India, in this very important area that is relevant to nearly all specialties, more so in the elderly population there is a need to support researchers to investigate delirium and generate relevant and clinically useful data for their settings. There should be more focus on delirium in the ICU, postoperative as well as in general medical ward settings, and LTC, to study the incidence and prevalence, clinical presentation, short-term and long-term consequences as well as possible prevention and treatment options. It would be equally important and relevant to study the risk factors that may be specific to a particular patient population.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (5th ed). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- [Google Scholar]

- Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275:852-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and clinical profile of delirium: a study from a tertiary-care hospital in north India. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:25-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence, prevalence, risk factor and outcome of delirium in intensive care unit: a study from India. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:639-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current practices of mobilization, analgesia, relaxants and sedation in Indian ICUs: A survey conducted by the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:575-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of delirium in elderly: a hospital-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:467-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family Welfare Statistics in India. 2011. Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/3503492088FW%20Statistics%202011%20Revised%2031%2010%2011.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:27-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in patients admitted to a cardiac intensive care unit with cardiac emergencies in a developing country: incidence, prevalence, risk factor and outcome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:156-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in an intensive care unit: a study of risk factors. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1297-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:591-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predisposing factors for delirium in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2001;5:265-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subsyndromal delirium in the ICU: evidence for a disease spectrum. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1007-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Implications of objective vs subjective delirium assessment in surgical intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:e12-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304:443-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, presentation and prognosis of delirium in older people in the population, at home and in long term care: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:127-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Partial and No Recovery from Delirium in older hospitalized adults: Frequency and baseline risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2340-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:955-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design and methods of the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), a multicomponent targeted intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients: efficacy and cost-effectiveness in Dutch health care. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in hospitalized older patients: recognition and risk factors. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1998;11:118-25. discussion 157-8

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) In: The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Vol X. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium and cognitive decline: more than a coincidence. Curr Opin Neurol. 2013;26:634-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The cholinergic system and inflammation: common pathways in delirium pathophysiology. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:669-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2011;40:23-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predisposing and precipitating factors of delirium after cardiac surgery: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1160-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring depth of anaesthesia in a randomized trial decreases the rate of postoperative delirium but not postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Brit J Anaesth. 2013;110(Suppl 1):i98-105.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2010. NICE clinical guideline 103. Delirium: diagnosis, prevention and management; Available from: www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13060/49909/49909.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119:229-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standardised frailty indicator as predictor for postoperative delirium after vascular surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:824-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium risk screening and haloperidol prophylaxis program in hip fracture patients is a helpful tool in identifying high-risk patients, but does not reduce the incidence of delirium. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Implications of objective vs subjective delirium assessment in surgical intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2012;21:12-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity and reliability of the CAM-ICU Flowsheet to diagnose delirium in surgical ICU patients. J Crit Care. 2010;25:144-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practical assessment of delirium in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:176-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium monitoring in the ICU: strategies for initiating and sustaining screening efforts. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:179-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Hospital Elder Life Program: A model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1697-706.

- [Google Scholar]

- NICE quality standard 63. Delirium in adults. July 2014. Available from: https://www. nice.org.uk/guidance/qs63

- [Google Scholar]

- NICE to HELP: Operationalizing National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines to improve clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:754-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness of multicomponent interventions to prevent delirium in older people admitted to medical wards. Age Ageing. 2012;41:285-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis, prevention, and management of delirium: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2010;341:c3704.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synopsis of the National institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline for prevention of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:746-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delirium in older persons: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:150-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacological treatment of dementia and mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:556-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- The association of psychotropic medication use with the cognitive, functional, and neuropsychiatric trajectory of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:1248-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevention and treatment options for postoperative delirium in the elderly. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:515-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:119-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence and consensus-based German guidelines for the management of analgesia, sedation and delirium in intensive care: short version. Ger Med Sci. 2010;8:Doc02.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with delirium. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(5 Suppl):1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antipsychotics in the treatment of delirium in older hospitalized adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(Suppl 2):S269-76.

- [Google Scholar]