Translate this page into:

Cytogenetic profile of aplastic anaemia in Indian children

Reprint requests: Dr Vineeta Gupta, Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221 005, India e-mail: vineetaguptabhu@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Aplastic anaemia is a rare haematological disorder characterized by pancytopenia with a hypocellular bone marrow. It may be inherited/genetic or acquired. Acquired aplastic anaemia has been linked to many drugs, chemicals and viruses. Cytogenetic abnormalities have been reported infrequently with acquired aplastic anaemia. Majority of the studies are in adult patients from the West. We report here cytogenetic studies on paediatric patients with acquired aplastic anaemia seen in a tertiary care hospital in north India.

Methods:

Patients (n=71, age 4-14 yr) were diagnosed according to the guidelines of International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anaemia Study. Conventional cytogenetics with Giemsa Trypsin Giemsa (GTG) banding was performed. Karyotyping was done according to the International System for Human Cytogenetics Nomenclature (ISCN).

Results:

Of the 71 patients, 42 had successful karyotyping where median age was 9 yr; of these 42, 27 (64.3%) patients had severe, nine (21.4%) had very severe and six (14.3%) had non severe aplastic anaemia. Five patients had karyotypic abnormalities with trisomy 12 (1), trisomy 8 (1) and monosomy 7 (1). Two patients had non numerical abnormalities with del 7 q - and t (5:12) in one each. Twenty nine patients had uninformative results. There was no difference in the clinical and haematological profile of patients with normal versus abnormal cytogenetics although the number of patients was small in the two groups.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Five (11.9%) patients with acquired aplastic anaemia had chromosomal abnormalities. Trisomy was found to be the commonest abnormality. Cytogenetic abnormalities may be significant in acquired aplastic anaemia although further studies on a large sample are required to confirm the findings.

Keywords

Aplastic anaemia

cytogenetics

karyotyping

pancytopenia

Aplastic anaemia (AA) is defined as pancytopenia with hypocellular bone marrow in the absence of an abnormal infiltrate and no increase in reticulin. The disease may be congenital/inherited or acquired. Presence of phenotypic abnormalities and the characteristic sensitivity of peripheral lymphocytes to DNA cross-linking agents (mitomycin C and diepoxybutane) points towards congenital form of aplastic anaemia i.e. Fanconi anaemia. Acquired aplastic anaemia has been linked to many drugs, chemicals and viruses. However, in a large number of cases no definite aetiology can be ascertained. Cytogenetic abnormalities in relation to acquired aplastic anaemia have been reported infrequently mostly from the West123. This is mainly because of difficulties in obtaining sufficient cells for analyses, especially at the onset of the disease when the bone marrow is hypocellular. Cytogenetic abnormalities acquire significance in view of the fact that hypocellular myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) may present as aplastic anaemia and it may be difficult to distinguish the two conditions based on morphology alone. The response to treatment may also be different in this situation45. There are no studies on cytogenetic abnormalities from India either in adults or children with acquired aplastic anaemia. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to evaluate the cytogenetic abnormalities in paediatric patients with acquired aplastic anaemia at the time of diagnosis.

Material & Methods

Patients: This prospective study included 71 consecutive patients with aplastic anaemia in the age group of 4-14 yr admitted from January 2009 to June 2011 over a period of 30 months in the Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India. Diagnosis was established according to the guidelines by International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anaemia Study6. Inclusion criteria for the patients were: hypocellular bone marrow on trephine biopsy with at least two of the following: haemoglobin <10g/dl, platelet count <50 × 109/l, neutrophil count <1.5 × 109/l4. Severity was graded according to criteria78 where a neutrophil count of <0.2 × 109/l was classified as very severe and <0.5 × 109/l as severe aplastic anaemia. Exclusion criteria were: patients with inherited bone marrow failure syndrome (IBMFS) where diagnosis was based on a detailed history including family history, complete physical examination, ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen and chromosomal fragility test with mitomycin C and patients who developed pancytopenia secondary to chemo/radiotherapy. Serology for hepatitis A, B, C and E was carried out in all the cases. Patients were treated according to standard protocol based on British Committee for Standards in Hematology (BCSH) Guidelines8. Patients received anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) followed by cyclosporine for 6 months. Those who could not afford immunosuppressive treatment due to financial constraints received only supportive treatment with blood products. Response to treatment was assessed according to published criteria9. Complete response (CR) was defined as haemoglobin (Hb) >10 g/dl, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) >1.5 × 109/l and platelet count >100 × 109/l. Partial response (PR) was defined when haematological parameters were not sufficient for a CR but there was increase from baseline values with at least Hb >7 g/dl, ANC > 0.5 × 109/l and platelet count >30 × 109/l. Response to treatment was assessed at 3 and 6 months. Growth factors were not used in the protocol. None of the patients underwent bone marrow transplantation during the study period. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital. Written informed consent was taken from the parents/guardians of the patients for collection of samples.

Methods: Bone marrow samples (0.5 ml) were collected in heparin for cytogenetic studies at the time of initial diagnosis. Sample was cultured in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, USA) medium supplemented with foetal calf serum and incubated at 37°C for 72 h. Colchicine (Sigma) was added 2 h prior to harvesting the culture for chromosome preparation. Culture was centrifuged and fresh suspension of cells was made with hypotonic KCl. Cell suspension was dropped on clean slides and flame dried. Giemsa Trypsin Giemsa (GTG) banding was performed after trypsinization10. At least 20 metaphases were analyzed at each examination. If less than 20 metaphases were observed, the result was considered to be uninformative. Karyotyping was performed according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN)11. Of the 71 patients, successful karyotyping was obtained in 42. Cytogenetic analysis was repeated at 6 months in patients who had abnormal karyotype at diagnosis.

Statistical analysis: Quantitative data were presented in mean ± standard deviation while qualitative data in number and percentage. Fisher's exact probability test was used to test statistical significance between the properties. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient profile: The median age of the patients who had successful karyotyping (n=42) was 9 yr (range 4-14 yr) with 31 males and 11 females. Mean haemoglobin, absolute neutrophil count and platelet count were 3.9 ± 1.86 g/dl, 0.46 ± 0.24 (× 109/l) and 16.13 ± 12.56 (× 109/l), respectively. Of these 42 patients, 27 (64.3%) had severe aplastic anaemia (SAA), nine (21.4%) had very severe aplastic anaemia (VSAA) and the remaining 6 (14.3%) had non severe aplastic anaemia (NSAA). Two patients had positive serology for hepatitis. One patient each was positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and anti HCV.

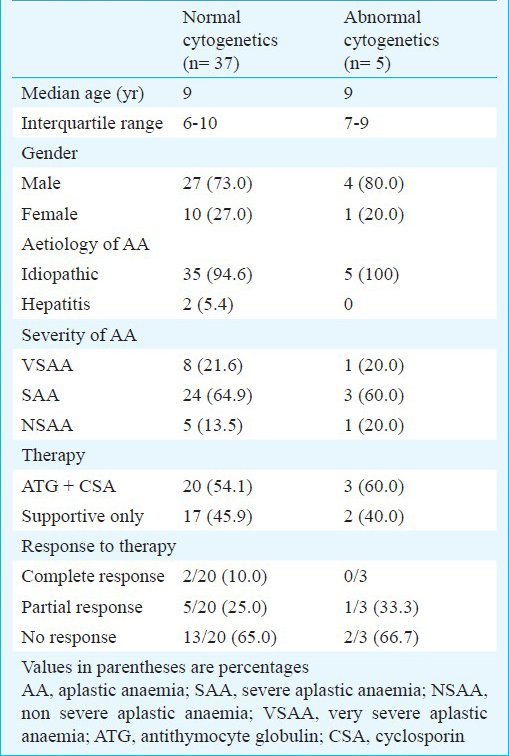

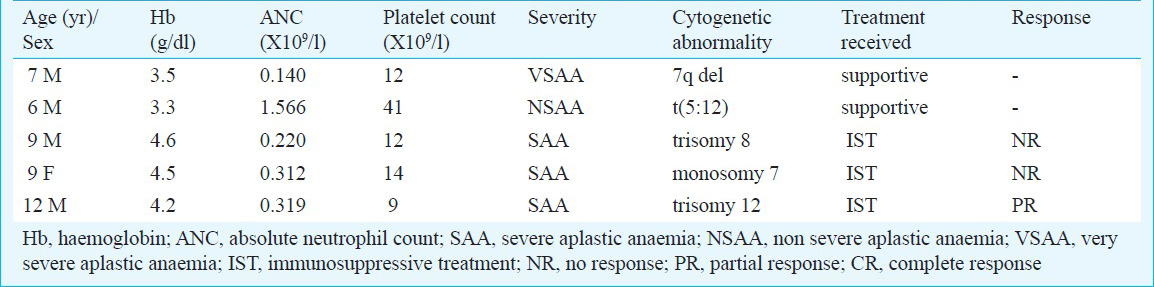

Cytogenetics: Cytogenetic studies were performed on 71 patients at the time of initial diagnosis of AA, of whom, 42 had successful result. The studies were uninformative in 29 patients due to failed culture, contamination or inadequate number of metaphases. Of the 42 patients with successful karyotyping, 37 had normal karyotype whereas five patients (11.9%, 95% CI 0.104-0.135) had abnormal karyotype (Table I). Three patients had numerical cytogenetic abnormality. One patient each had del 7 q- and t (5:12) (Table II). Repeat cytogenetic analysis could be carried out in four patients only as one patient succumbed to intracranial haemorrhage 4 months after diagnosis. The cytogenetic abnormalities were same as observed initially at the time of diagnosis in these patients.

Response to therapy: Only 23 patients (20 with normal and 3 with abnormal karyotype) received immunosuppressive treatment (IST) with ATG and cyclosporine. Remaining patients could not afford IST due to financial constraints. In the patients with normal karyotype (n=20), two had complete response, five had partial response and the remaining 13 patients had no response and remained transfusion dependent at 3 months. Of those with abnormal karyotype (n=3), one had partial response whereas the remaining two had no response (Table I). There was no significant difference with respect to patient profile and disease characteristics between the groups with normal and abnormal karyotype.

Discussion

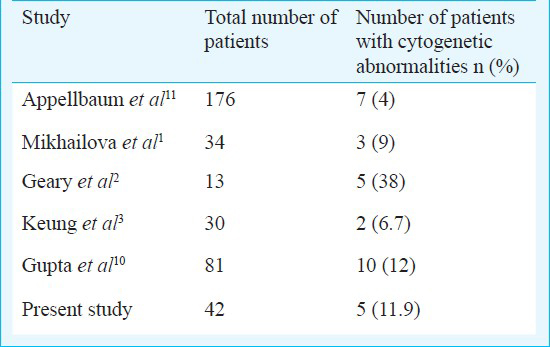

Aplastic anaemia is a rare haematological disorder which is thought to be immune mediated. It is characterized by T-cell mediated organ-specific destruction of bone marrow haematopoetic cells. The incidence has been reported to be 2.0/million by International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anaemia Study in Europe12. It has been noted to be 2 to 3 times higher in Asia than in Europe13. Rarity of the disease with low incidence of karyotypic abnormalities coupled with difficulties in cell culture of a hypoplastic/aplastic marrow has prompted limited studies. In the present study, cytogenetic abnormalities were observed in 11.9 per cent patients. Trisomy was the commonest abnormality being present in two patients followed by monosomy in one patient. Non numerical karyotypic abnormality was found in two patients. Two patients had characteristic cytogenetic abnormality found in myelodysplastic syndrome. The morphological diagnosis was aplastic anaemia in both the cases. Other studies have noted an incidence of 4-38 per cent in patients of aplastic anaemia where cytogenetic studies were carried out at diagnosis (Table III)1231415. Trisomy was found to be the commonest cytogenetic abnormality12. Some centers have a stringent initial diagnostic criteria and abnormal cytogenetics excludes a diagnosis of aplastic anaemia regardless of marrow morphology4. Based on this, presence of a karyotypically abnormal clone changes the diagnosis of aplastic anaemia to MDS. However, in other studies no such distinction has been made14 and patients with an abnormal cytogenetics are labelled as aplastic anaemia only. In our study, all patients had a morphological diagnosis of aplastic anaemia and were classified as such. There was no difference in the clinico-haematological profile of patients with normal and abnormal cytogenetics.

The relevance of cytogenetic abnormalities in the pathophysiology of aplastic anaemia is not very clear. It has been suggested that the distinction between AA and hypoplastic myelodysplasia can be difficult on morphological grounds16, and in this situation an abnormal karyotype might suggest the diagnosis of hypoplastic MDS121517. Immunosuppressive therapy with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine is highly effective in AA whereas therapeutic options for hypoplastic MDS are limited, with a median survival of only 32 months without stem cell transplantation16. ATG may improve the pancytopenia in MDS14 but the response is inferior to aplastic anaemia. In this situation identification of an abnormal karyotype may have a prognostic significance as a poor response to immunosuppressive therapy may be expected. In the present study, two patients had cytogenetic abnormalities typical of MDS and both had poor response to immunosuppressive therapy.

The treatment response of patients with normal and abnormal cytogenetics after immunosuppressive treatment was also compared. There was no significant difference in the response rate in the two groups. The limitation was small number of patients who received IST. This is evident from the scanty data available on IST in paediatric aplastic anaemia patients in the published literature from our country1920. Studies from developed countries have compared the outcome of patients with normal versus abnormal cytogenetics at diagnosis after IST and found no significant difference in survival14. However, in one study more deaths due to leukemic transformation occurred in patients with complex cytogenetic abnormalities4. Also those patients who had persistent karyotypic abnormalities were more at risk of developing myelodysplastic syndrome or acute leukemia. In another study carried out in adults with aplastic anaemia, abnormal cytogenetics was associated with higher leukemic transformation and poor response to immunosuppressive therapy21. Use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in treatment of aplastic anaemia is associated with variable response. Acute leukemia has been reported to occur after G-CSF therapy. Ohga et al5 reported 11 (22%) of 50 children treated with cyclosporin and G-CSF who developed myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia.

Mean duration of follow up was 16 months (range 10-28 months). None of the patients developed acute leukemia during this period. Cytogenetic study was repeated at 6 months in those patients who had abnormal findings initially and found no change, but the numbers are small to make a meaningful conclusion. It is also difficult to comment on the transformation of aplastic anaemia to acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome from the present study as the follow up period is not adequate. This is an inherent problem with study of aplastic anaemia in our set up as the patients who do not receive definitive therapy or do not respond to therapy are either lost to follow up due to their inability to arrange transfusion support or succumb to the complications of the disease.

In conclusion, our study provides the cytogenetic profile of acquired aplastic anaemia in children from India. It reports some of the karyotypic abnormalities observed typically in myelodysplastic syndrome. It also suggested that the clinical and haematological profile of patients with abnormal cytogenetics was similar to those with normal cytogenetics. However, due to the small number of patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy, no definite conclusion regarding the influence of abnormal cytogenetics on the treatment outcome could be drawn. Due to markedly hypocellular bone marrow cytogenetic studies are difficult to perform in aplastic anaemia and more studies are needed from other parts of the country to answer specific questions.

References

- Cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with severe aplastic anemia. Haematologica. 1996;81:418-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abnormal cytogenetic clones in patients with aplastic anemia: response to immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Haematol. 1999;104:271-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bone marrow cytogenetic abnormalities of aplastic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2001;66:167-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distinct clinical outcomes for cytogenetic abnormalities evolving from aplastic anemia. Blood. 2002;99:3129-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment responses of childhood aplastic anemia with chromosomal aberrations at diagnosis. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:313-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of aplastic anemia: relevance of diagnostic criteria. Blood. 1987;70:1718-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selection of patients for bone marrow transplantation in severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 1975;45:355-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acquired aplastic anemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;123:782-801.

- [Google Scholar]

- What is the definition of cure of aplastic anaemia? Acta Haematologica. 2000;103:16-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- ISCN: an International System for Human Cytogenetics Nomenclature. Basel: Karger; 1991.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathophysiologic mechanisms in acquired aplastic anemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006:72-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical relevance of cytogenetic abnormalities at diagnosis of acquired aplastic anemia in adults. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:95-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with otherwise typical aplastic anemia. Exp Hematol. 1987;15:1134-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypocellular myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS): new proposals. Br J Haematol. 1995;91:612-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytogenetic abnormalities in aplastic anemias. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;7(Suppl 1):268a. (abstract)

- [Google Scholar]

- Antithymocyte globulin for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Br J Haematol. 1997;99:699-705.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival after immunosuppressive therapy in children with aplastic anemia. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:371-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine in children with aplastic anemia. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:229-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- The characteristics and clinical outcome of adult patients with aplastic anemia and abnormal cytogenetics at diagnosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:844-50.

- [Google Scholar]