Translate this page into:

Cervical length measurement in nulliparous women at term by ultrasound & its relationship to spontaneous onset of labour

Reprint requests: Dr Joydev Mukherji, IX/7Citizens, 103 Maniktola Main Road, Kolkata 700 054, West Bengal, India e-mail: joydevmukherji@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Data on serial cervical length (CL) measurements in pregnancy at term to predict spontaneous labour onset are scarce and conflicting. This study was conducted to observe CL changes preceding spontaneous onset of labour, by serial transvaginal sonography (TVS) and transabdominal sonography (TAS), in nulliparous Indian women near term.

Methods:

Only nulliparous women with a singleton foetus in cephalic presentation and who confirmed their gestational age were recruited. Sonographic CL measurements were taken at weekly intervals from 36 wk gestation onwards by a single ultrasonologist. Transabdominal and transvaginal measurements were undertaken using the suitable transducer probes with the women in the supine position.

Results:

A total of 104 women with spontaneous onset of labour were evaluated. There was substantial variation in CL measurements, both by TVS and by TAS, from 36 to 40 wk gestation, although the two sets of measurements correlated closely. Mean CL changed significantly over the last three weeks before delivery. However, only one-third of the women showed CL change of >5 mm per week in the last three weeks. There was poor correlation between gestational age at delivery and the last measured CL, either by TVS or TAS. Length >3.1 mm, measured by TVS at 38 wk gestation, predicted post-dated pregnancy to a limited extent.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Inter-individual variations in CL and in CL changes were large. Thus, it was not practical to predict spontaneous onset of labour by sonographic CL measurement near term. Post-dated pregnancy may be predicted with limited success. Further studies should explore other parameters, in addition to CL.

Keywords

Cervical length

nulliparous

onset of labour

term

transabdominal sonography

transvaginal sonography

ultrasound

Cervical length (CL) measurement in mid-pregnancy by the transvaginal sonography (TVS) has been extensively studied for prediction of preterm labour. However, data on term pregnancy are limited. Several methods have been tried to assess the remodelling and ripeness of the cervix before labour induction and newer methods are being sought123. The few existing studies in asymptomatic pregnant women have focussed mainly on the gestational timeframe very close to delivery, either before induction of labour or in post-dates pregnancies.

Two studies reported that the positive predictive value (PPV) of a single CL measurement in term pregnancy was as good as digital examination of the cervix in predicting spontaneous onset of labour within seven days45. Ramanathan et al6 found that measurement of CL at 37 wk could define the likelihood of spontaneous delivery before 40 wk and 10 days. Meijer-Hoogeveen et al7 concluded that variations in CL and in CL changes were large, which hampered the value of single and repeated CL measurements for the prediction of spontaneous onset of labour at term. Souka et al8 indicated that it was feasible to utilize cervical measurements in the third trimester to calculate the probability of delivery at any gestational age by CL assessment. Thus, the issue of predicting spontaneous onset of labour by sonographic CL measurement at term remains unsettled.

Though intrusive, TVS has been widely used for CL measurement because, unlike transabdominal sonography (TAS), it is not affected by maternal obesity, oligohydramnios, bladder filling, attenuated echoes of the foetal head or artificially lengthened cervical dimensions caused by bladder compression9. Although TVS remains the reference standard for assessing the cervix10, TAS is non-intrusive and more acceptable and may also provide an effective means of assessing the cervix. The utility of transabdominal assessment of CL has been reported911. Furthermore, TAS may be the only applicable technique in certain clinical scenarios in which vaginal examination needs to be restricted.

Measurement of CL in late pregnancy could help predict the spontaneous onset of labour and could assist clinicians in assessing favourability for the induction of labour. We hypothesized that the spontaneous onset of labour, including post-dated pregnancy, might be predicted by sonographic CL measurement. The objective of the present study was to observe CL changes preceding spontaneous onset of labour, by serial ultrasound examination (both TAS and TVS), in nulliparous Indian women near term and to decide whether the measurements could be used in prediction of the time of onset of spontaneous labour and whether post-dated pregnancy could also be predicted.

Material & Methods

The study was designed as an observational study with longitudinal follow up conducted in the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, R.G. Kar Medical College, Kolkata, India, after approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. All women gave written informed consent at the time of enrolment.

Consecutive consenting nulliparous women with a singleton foetus in the cephalic presentation were selected during May 2010 to April 2011 from the antenatal outpatient clinic of the department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of a tertiary teaching hospital in Eastern India. For ensuring confirmed gestational age, only those women who had ultrasound in either the first or the second trimester (before 20 wk) were included. Exclusion criteria were admission for threatened preterm labour earlier in pregnancy, previous uterine surgery, uterine malformations or leiomyoma, foetal anomaly or death and foetal or maternal complication that could dictate labour induction or caesarean section before the onset of spontaneous labour.

Sonographic CL measurements were taken at weekly intervals from 36 wk gestation onwards. With the woman in a supine position and with a full bladder, the length of the cervix was measured by TAS (3.5 MHz sector transducer; AGILENT, Philips Medical Systems, Netherlands). Subsequently, CL was measured by TVS (7.5 MHz transvaginal transducer; AGILENT, Philips Medical Systems) with the bladder empty. The transvaginal ultrasound probe was withdrawn until a sagittal view of the cervix was obtained without distortion of the shape by pressure of the ultrasound probe. An adequate image for the measurement of CL was defined as the visualization of the internal os, external os and endocervical canal. The CL was measured, with electronic callipers, as the linear distance between the external os and the internal os along a closed endocervical canal. All measurements were carried out by a single ultrasonologist. After the procedure, the woman was advised to return the following week or to attend hospital for admission, if labour pain started.

Statistical analysis: Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to quantify the associations between normally distributed numerical variables. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess significance of within-subject difference in CL measurements by TAS and TVS in the last three weeks before the spontaneous onset of labour. Categorization of women by extent of week-to-week change in CL by TVS in last three weeks was done defining ‘minimal change’ as a change of <5 mm per week. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn to decide the best CL (measured by TVS and TAS at 38 wk gestation) cut-off for the prediction of pregnancy extending beyond 40 completed wk of gestation i.e. post-dated pregnancy. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for the cut-off with 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs). Statistica version 6 (StatSoft Inc., 2001, Tulsa, Oklahoma) and MedCalc version 11.6 (MedCalc Software, 2011, Mariakerke, Belgium) softwares were used for analysis.

Results

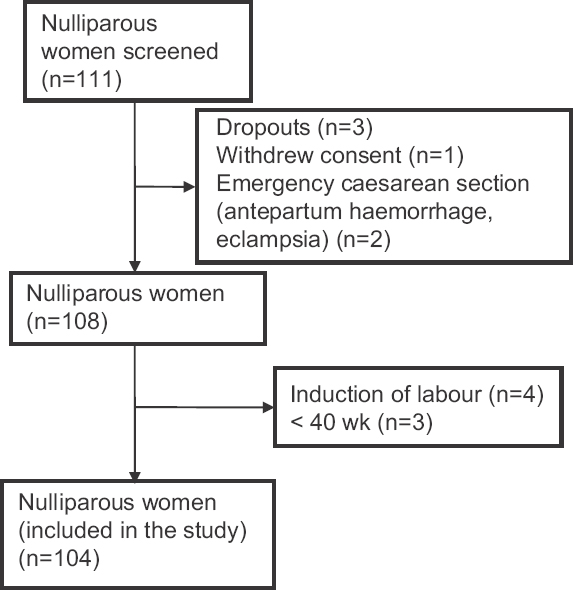

A total of 111 nulliparous women were screened, of whom 104 were taken for final evaluation (Fig. 1). Maternal age was 25.3±3.12 (range 20-32) yr and the gestational age at delivery was 278.5± 5.19 (range 261-288) days. Of the 104 women with spontaneous onset of labour, 99 delivered vaginally and five women underwent emergency caesarean section, of whom one was for failure to progress in labour.

- Flowchart depicting flow of study participants.

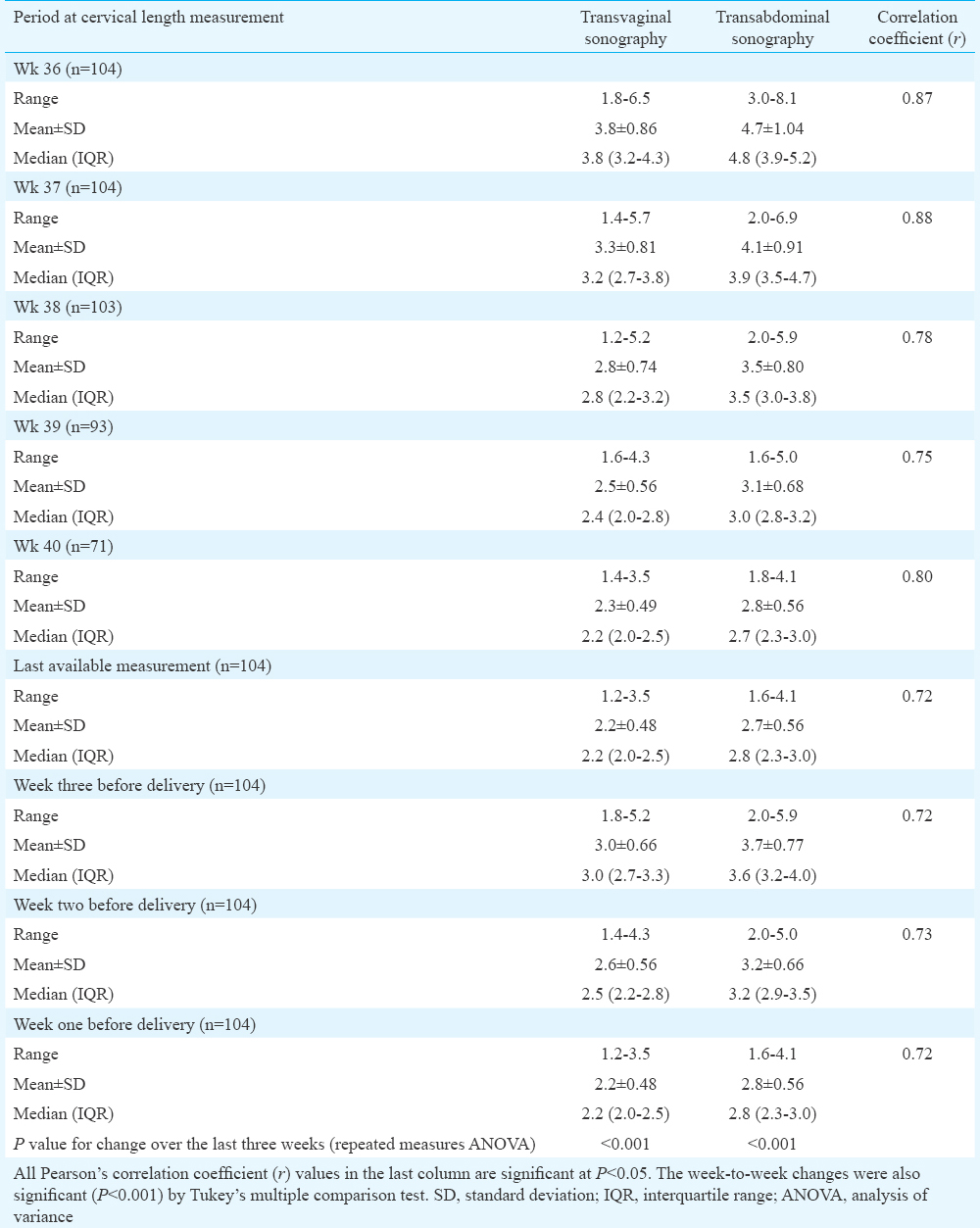

The descriptive summary of weekly CL measurements, by TVS and TAS, is shown in the Table. There was significant correlation between CL measurements by TAS and TVS. There was also correlation between the last TAS and the last TVS measurement (r=0.72). Comparison of changes in the mean CL across the last three weeks of gestation revealed that the week-wise difference between CLs, whether measured by TVS or TAS, was significant (P<0.001).

There was, however, no correlation between gestational age at delivery and the last measured CL by either TVS (r=0.16) or TAS (r=0.04). There was also no correlation between ultrasound-delivery interval and CL, irrespective of the gestational week (r=−0.15, −0.17, −0.09, 0.02, 0.14 for measurements by TVS between wk 36 and 40; r=−0.04, −0.16, −0.16, −0.19, −0.02 for measurements by TAS in the corresponding weeks).

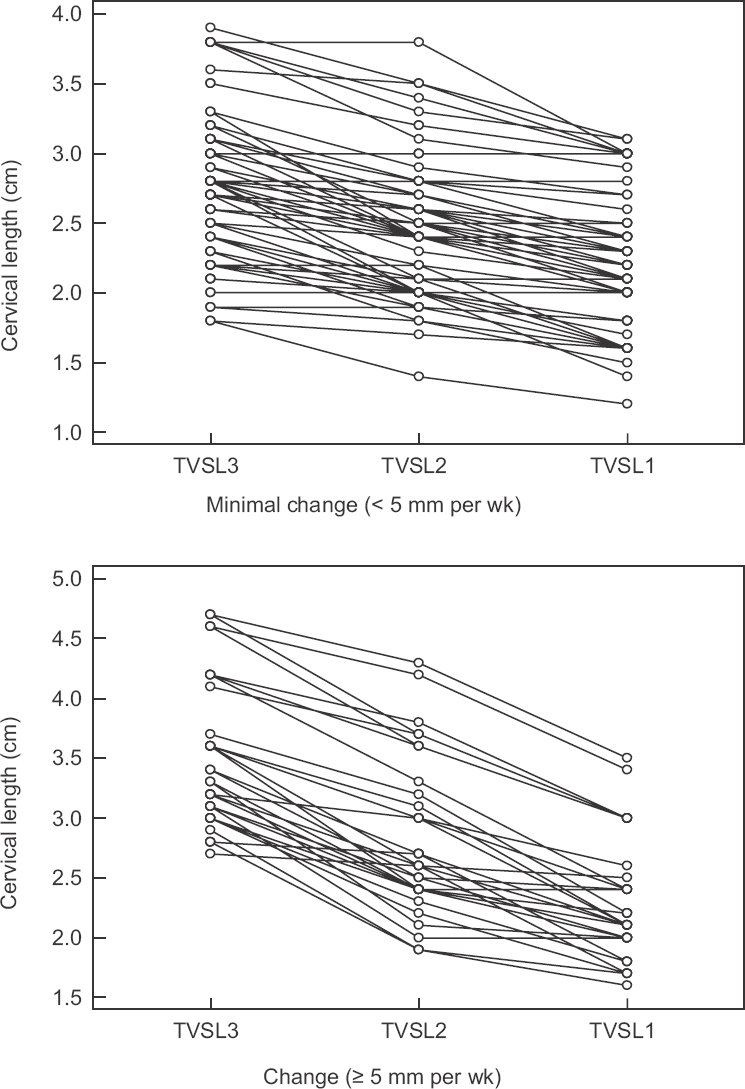

When individual changes in CL over the last three weeks before delivery were plotted, two different patterns were observed among the women (Fig. 2) – those in whom CL change was minimal (defined as decrease in CL < 5 mm per week; n=70, 67.31%) and those in whom CL decreased by ≥5 mm per week (n=34, 32.69%). Thus, majority of the women did not have a change of ≥5 mm per week.

- Plots showing cervical length changes by transvaginal sonography over the last three weeks (TVSL3, TVSL2 and TVS1 depicting the measurements in each week) – the study group can be categorized into women with minimal change (<5 mm per week; n=70) and women with change (≥5 mm per week; n = 34).

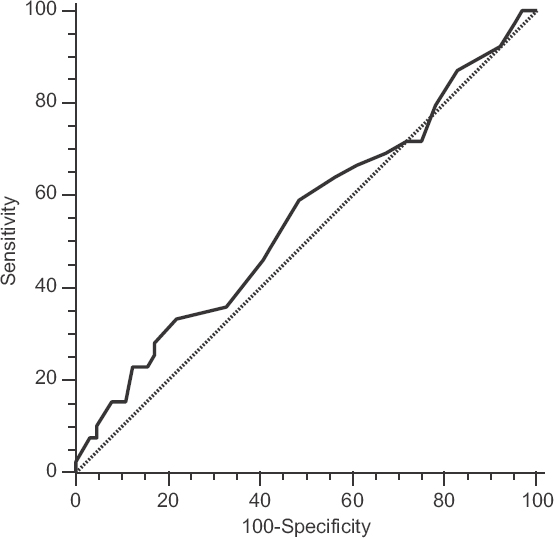

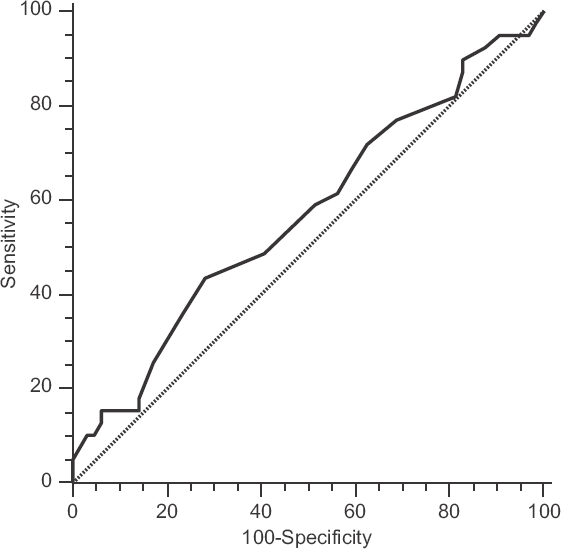

Fig. 3 shows the ROC curve constructed for CL measured by TVS at 38 wk gestation to decide cut-off for predicting occurrence of post-dated pregnancy. It suggested that if CL measured by TVS at 38 wk was >3.1 cm, then post-dated pregnancy was best predicted. However, the plot did not have a clear elbow (ROC space area 0.551; 95% CI 0.450-0.649), and for the point selected, sensitivity (33.3%; 95% CI 19.1-50.2%) and specificity (78.1%; 95% CI 66.0-87.5%) were not satisfactory. A similar situation was noted for the ROC curve for TAS (Fig. 4). The cut-off value for predicting post-dated pregnancy by TAS at 38 wk was 3.6 cm with sensitivity 43.6 per cent (95% CI 27.8-60.4%) and specificity 71.8 per cent (95% CI 59.2-82.4%) values suboptimal. The ROC space area, in this case, was almost similar at 0.570 (95% CI 0.468-0.667).

- Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of cervical length measurement by transvaginal sonography at 38 wk to decide cut-off for prediction of post-dated pregnancy. There is no clear elbow but the cut-off identified corresponds to cervical length >3.1 cm.

- Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of cervical length measurement by transabdominal sonography at 38 wk to decide cut-off for prediction of post-dated pregnancy. There is no clear elbow but the cut-off identified corresponds to cervical length >3.6 cm.

Discussion

The study showed large inter-individual variations in CL and also in CL changes before the spontaneous onset of labour at term. For predicting the spontaneous onset of labour, a single CL measurement at any point in pregnancy did not prove useful because of the large and unpredictable variability of CL. Previous studies have reported normal ranges for CL during pregnancy12131415.

The correlations between CL measurements by TAS and TVS for every gestational week were significant. The results were similar to the study by Saul et al16, who found that there was no difference between mean transabdominal and transvaginal CLs. The last CL measurement taken for each woman, whether measured by TVS or TAS, correlated only weakly with the time until spontaneous onset of labour. Further, CL was not correlated with gestational age at delivery in the period investigated in this study i.e. ≥36 wk. There was also no relation between gestational age at delivery and the ultrasound examination-delivery interval.

Meijer-Hoogeveen et al7 have concluded that between 37 and 38 wk gestation, spontaneous onset of labour before 41 wk can be predicted by a CL measurement but with low sensitivity and poor NPV. In addition, the last CL measurement taken for each woman was only weakly correlated with the time until spontaneous onset of labour, and even in the last 48 h before delivery, a quarter of their population still had CL >30 mm. Further, CL was not correlated with gestational age in the period investigated in that study i.e. ≥36 wk7. Zorzoli et al17 found that gestational age at delivery did not correlate with cervical dimensions at any stage of pregnancy. Another study concluded that the Bishop score and ultrasonographic measurement of CL were valuable for predicting the onset of spontaneous labour within seven days only when these assessments were performed close to term4. Vimercati et al18 found significantly shorter CL at 39 and 40 wk of gestation in a group who had spontaneous onset of labour before 41 completed wk of gestation, compared to those who did not, but could not find any cut-off value for CL that was predictive. Souka et al8 found that a significant proportion of pregnancies destined to deliver at term had short cervical measurements.

In this study, majority of women did not show a change ≥5 mm per week. Meijer-Hoogeveen et al7 found that women with spontaneous onset of labour could be divided into three groups: those with unchanged CL before delivery; those with a fall in CL in the last two weeks before delivery and those with a gradual change in CL starting before the last two weeks before delivery. They also demonstrated large inter-individual variations in CL changes before the spontaneous onset of labour at term, and found a decrease in CL preceding labour in only half of their sample, which was either gradual over several weeks or within the last two weeks before delivery, while in the others, CL remained unchanged until shortly before delivery. In our study, a notable decrease in CL preceding labour was observed in only a third of our sample, which was over the last three weeks before delivery. In others, CL remained largely unchanged until shortly before delivery.

It was ascertained that CL >31 mm by TVS at 38 wk gestation could predict post-dated pregnancy to some degree although the diagnostic indices were not optimum. Meijer-Hoogeveen et al7 found that a single CL measurement <30 mm, between 37 and 38 wk of gestation, predicted spontaneous onset of labour before 41 wk gestation with a sensitivity of 46 per cent, specificity of 78 per cent, PPV of 82 per cent and NPV of 40 per cent in the supine position and sensitivity of 53 per cent, specificity of 72 per cent, PPV of 81 per cent and NPV of 40 per cent in the upright position.

This study had two major limitations. First, it was not continued beyond 40 completed gestational wk, and hence, it was not clear what happened to the cervical changes in post-dated pregnancy. Second, only one cervical parameter, namely the CL was studied, for the prediction of spontaneous onset of labour which might not be sufficiently discriminatory; other parameters such as cervical width, funnelling of the internal os and sludging could have been considered as a composite index for possible prediction of impending labour.

In conclusion, the changes occurring in the cervix over the last few weeks of pregnancy were heterogeneous and did not show any consistent pattern. This large variability limits the utility of CL measurement for prediction of spontaneous onset of labour near term by either a single or repeated assessments. CL >31 mm measured by TVS or >36 mm by TAS at 38 wk gestation can predict post-dated pregnancy to a limited extent. Ultrasound measurements of CL alone in nulliparous women at term were not practical in the prediction of spontaneous onset of labour. Future studies should address other cervical parameters in addition to the length of cervix.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Development of an ultrasonic method to detect cervical remodeling in vivo in full-term pregnant women. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:2533-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methods for assessing pre-induction cervical ripening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (6):CD010762.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful induction of labor: Prediction by preinduction cervical length, angle of progression and cervical elastography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44:468-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the bishop score, ultrasonographically measured cervical length, and fetal fibronectin assay in predicting time until delivery and type of delivery at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:108-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of spontaneous onset of labor at term: The role of cervical length measurement and funneling of internal cervical os detected by transvaginal ultrasonography. Am J Perinatol. 2005;22:35-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound examination at 37 weeks’ gestation in the prediction of pregnancy outcome: The value of cervical assessment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:598-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sonographic longitudinal cervical length measurements in nulliparous women at term: Prediction of spontaneous onset of labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:652-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length in late second and third trimesters: A mixture model for predicting delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:308-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical assessment at the routine 23-weeks’ scan: Problems with transabdominal sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:292-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:567-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in bladder volume and the ultrasound appearance of the cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:457-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical length in normal pregnancy as measured by transvaginal sonography. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;58:313-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Charts for cervical length in singleton pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:161-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transvaginal sonographic examination of the cervix in asymptomatic pregnant women: Review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19:302-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is transabdominal sonography of the cervix after voiding a reliable method of cervical length assessment? J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1305-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cervical changes throughout pregnancy as assessed by transvaginal sonography. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:960-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The value of ultrasonographic examination of the uterine cervix in predicting post-term pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2001;29:317-21.

- [Google Scholar]