Translate this page into:

Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19: An evidence-based narrative review

For correspondence: Dr Ankur Gupta, Department of Cardiology, Advanced Cardiac Centre, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh 160 012, India e-mail: ag_pgi@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The recent outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, primarily involves the respiratory system with viral pneumonia as a predominant manifestation. In addition, SARS-CoV-2 has various cardiovascular manifestations which increase morbidity and mortality in COVID-19. Patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases and conventional cardiovascular risk factors are predisposed for COVID-19 with worse prognosis. The possible mechanisms of cardiovascular injury are endothelial dysfunction, diffuse microangiopathy with thrombosis and increased angiotensin II levels. Hyperinflammation in the myocardium can result in acute coronary syndrome, myocarditis, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death. The high level of cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides in the early course of COVID-19 reflects an acute myocardial injury. The complex association between COVID-19 and cardiovascular manifestations requires an in-depth understanding for appropriate management of these patients. Till the time a specific antiviral drug is available for COVID-19, treatment remains symptomatic. This review provides information on the cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19.

Keywords

ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers

ACE-2

coronavirus disease 2019

cytokine storm

endothelial dysfunction

heart failure

MERS

myocarditis

SARS-CoV-2

The World Health Organization declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a pandemic on March 11, 2020. The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, which causes COVID-19, was first detected in Wuhan, China, on December 12, 2019123. SARS-CoV-2, the seventh member of the family of human-infecting coronaviruses, which includes SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), has infected 60,074,174 people and killed 1,416,292 people globally till November 26, 20204. In India, SARS-CoV-2 has infected 9,256,223 people and killed 136,696 people till November 29, 20205. Although SARS-CoV-2 infects people of all age groups, elderly people with underlying cardiovascular diseases and those with conventional cardiovascular risk factors including male sex, diabetes, obesity and hypertension are particularly vulnerable with high morbidity and mortality67. Furthermore, patients may have varied cardiovascular manifestations either upfront or after the resolution of symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection. Multiple case studies have noted acute coronary syndrome (ACS)8, myocarditis9, cardiac arrhythmias10 and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest as terminal events in patients with COVID-1911. This review was aimed to provide updated information on the manifestations of COVID-19.

Epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans; SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can cause severe disease, whereas the remaining four coronaviruses, that is HKU1, NL63, OC43 and 229E, are usually associated with mild symptoms and account for around 15-30 per cent cases of common cold1213. Similar to SARS-CoV-1, bats likely served as reservoir hosts for SARS-CoV-2, and pangolins as the intermediate host, although this is not confirmed14. The early transmission data from Wuhan, China, showed that the median age of patients was 59 yr and mean incubation period was 5.2 days. The initial doubling time was 7.4 days; the basic reproductive rate was estimated to be 2.215.

SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV

The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the receptor for both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-Cov-212. Aerosol and surface stability is similar for both16. The SARS-CoV-2 shares 80 per cent sequence homology with SARS-CoV-117. The incubation period for all the three coronaviruses is around 2-12 days. Person-to-person transmission is assessed by the basic reproduction number (R0). The R0 for SARS-CoV-1 was 3; for MERS-CoV, R0 was 2-5 and for SARS-CoV-2, it was 2-312. It means that one patient of COVID-19 can spread infection to 2-3 susceptible persons.

Relationship of SARS-CoV-2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor

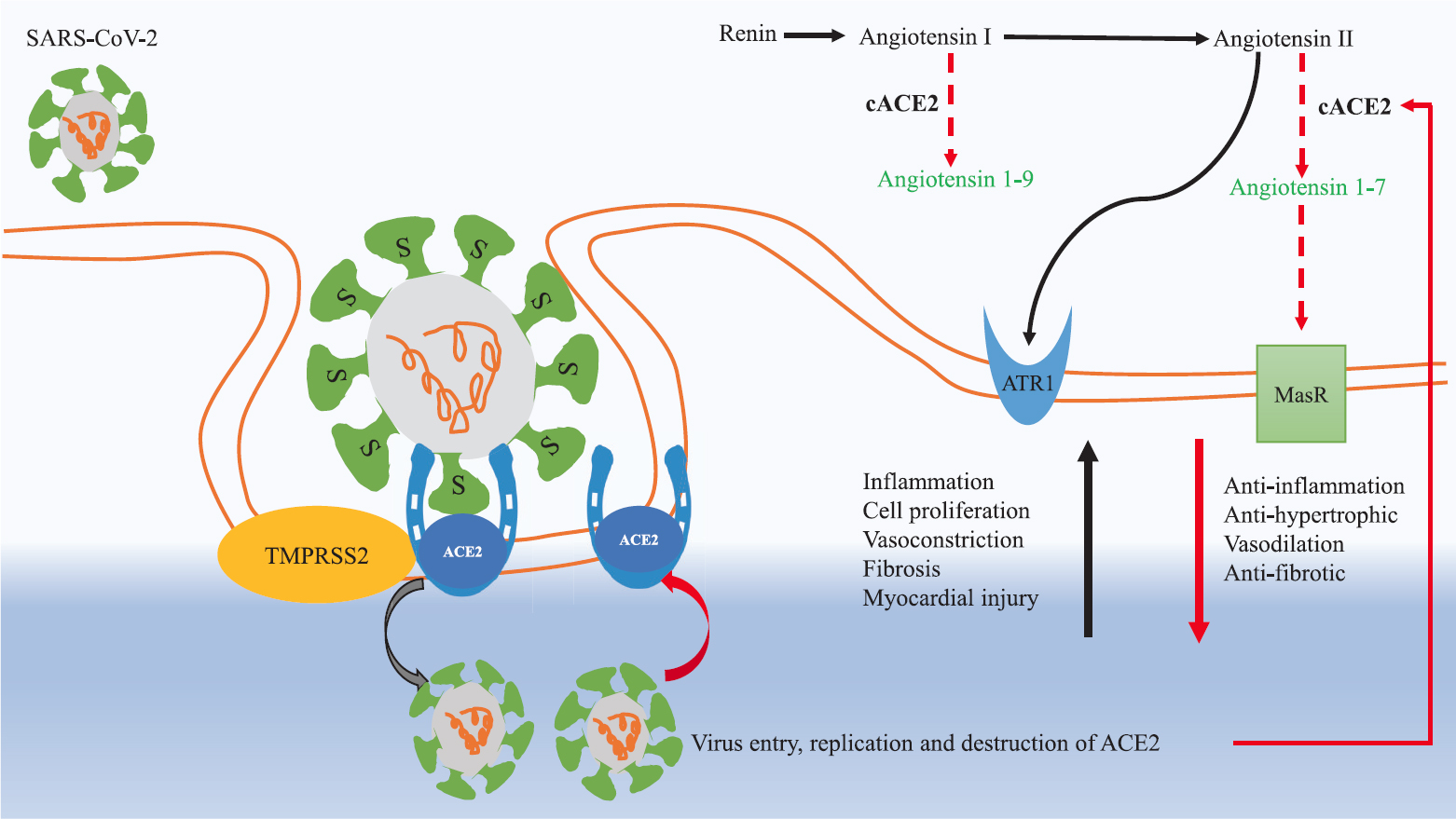

SARS-CoV-1 enters into the cell with the help of viral surface protein S (spike), which facilitates the first step in the virus replication cycle into the target cells. The S protein has two subunits - S1 and S2. The S1 subunit engages with membrane-bound cellular receptor carboxypeptidase ACE2 present over the cell membrane of lung epithelial cells (pulmonary alveolar type II cells), and the S2 subunit stalk mediates fusion to the infected cell318. TMPRESS2 (transmembrane protease serine 2) aids the ACE2 receptor for internalization of the virus1718. After internalization inside the cell, SARS-CoV-2 duplicates, proliferates and downregulates ACE2. ACE2 acts like the gatekeeper of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway, catalyzes angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7, and has vasodilatory action in the circulatory system. The low levels of circulating ACE2 in COVID-19 perpetuate the RAAS pathway. ACE2 receptors are also present over the lymphocytes/dendritic cells, gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidney, neurons and myocardium. High angiotensin II levels in the circulatory system cause inflammation, vasoconstriction, myocardial injury and thrombosis171819 (Fig. 1).

- Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19.The S1 subunit of spike S protein on the virus surface engages with membrane-bound cellular receptor carboxypeptidase ACE2 present over the cell membrane of lung epithelial cells (pulmonary alveolar type II cells), and S2 subunit stalk helps in cell fusion. TMPRSS2 protease aids in the attachment of ACE2 with virus S protein. After entry inside the cell, the virus replicates and destroys ACE2. The decrease in ACE2 (transmembranous and circulatory) perpetuates the RAAS pathway. Increase in angiotensin II levels in COVID-19 causes widespread injury by activation of ATR1 receptors. Activation of ATR1 causes vasoconstriction, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, acute lung injury and myocardial injury. The physiological function of ACE2 is to degrade angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7, and angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Angiotensin 1-7 acts on MasR receptors on cell membranes, and has vasodilatory and antifibrotic effects. Black arrows represent upregulation and red arrows represent downregulation in COVID-19. ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ATR1, angiotensin II receptor 1; cACE2, circulatory angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; MasR, mitochondrial assembly receptor; RAAS, rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2. Source: Refs 171819.

COVID-19 and cardiovascular risk factors

Multiple case series and retrospective studies have confirmed the association of cardiovascular risk factors with COVID-19 mortality. Initial large studies were from China and later Italy and the USA added to it, confirming the association of COVID-19 mortality with cardiovascular risk factors. In a recent series of 5700 patients of COVID-19 in the New York City, USA, the most common cardiovascular disease was hypertension in 56.6 per cent of patients, coronary artery disease (CAD) in 11.1 per cent of patients, congestive heart failure in 6.9 per cent, obesity in 41.7 per cent of patients and diabetes in 33.8 percent of patients20. An initial larger study from China analyzed the demographic profile of 44,672 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and showed that 4.2 per cent patients had cardiovascular diseases, 12.8 per cent had hypertension and 5.3 per cent diabetes. The limitation of this study was that it was not age adjusted and missing data on comorbid conditions in 53 per cent of cases21. In other two small single-centre studies on COVID-19, the cardiovascular disease was present in 15 and 14.5 per cent of patients1422. The study of 144 patients with COVID-19 from India reported diabetes mellitus in 11.1 per cent, hypertension in 2.1 per cent and CAD in 0.7 per cent patients23. The spectrum of cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 is highly variable from asymptomatic myocardial injury to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. In the COVID-19 pandemic, the cumulative incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest has increased significantly in Italy11.

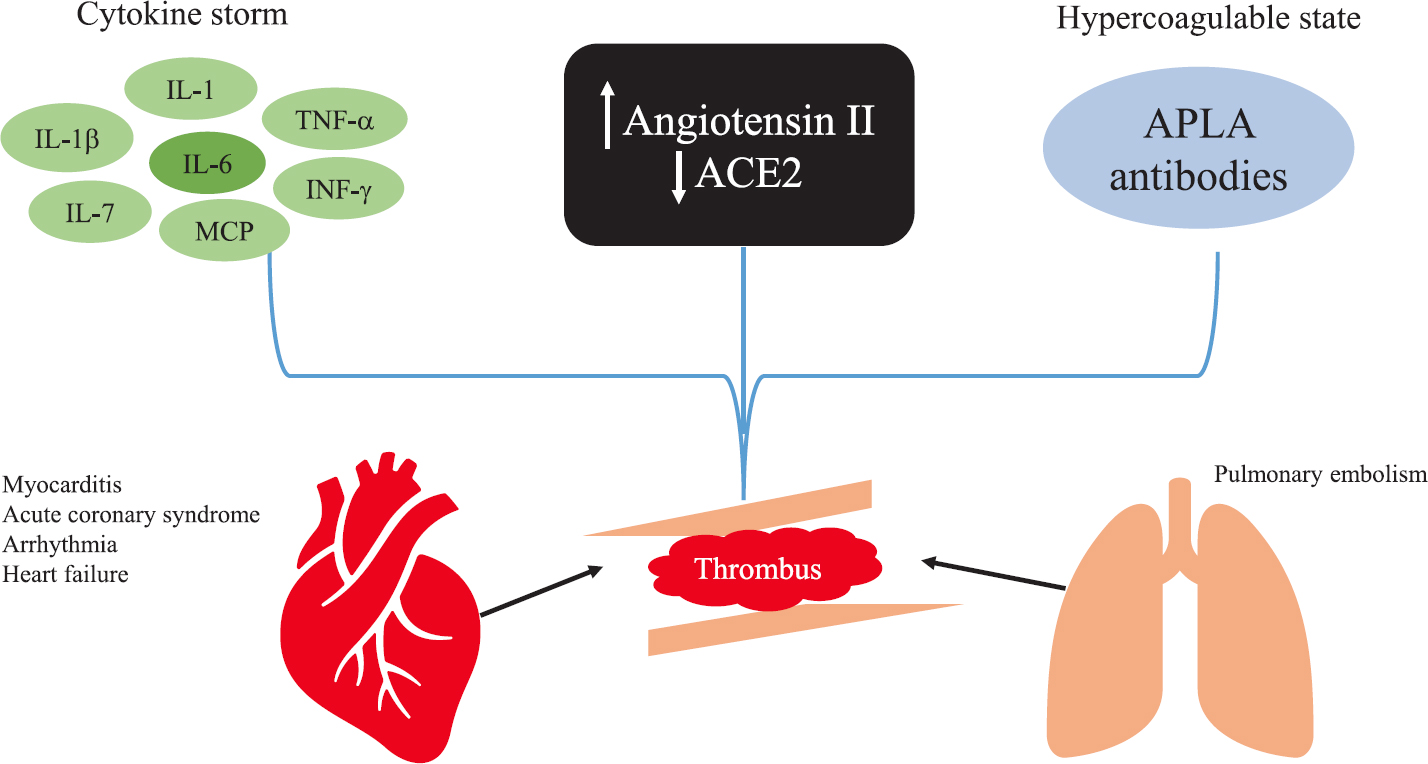

The cardiovascular manifestations of SARS-CoV-1 can be attributed either to direct viral injury or to an immunological response to the virus, as we see in myocarditis2425 (Fig. 2). Direct invasion of the heart by the virus has been found in sporadic autopsy studies in SARS-CoV-1, and in a few cases of SARS-CoV-2262728. The pathological specimen of COVID-19 patients revealed microvascular inflammation and thrombosis. Localized macrophage activation releases cytokine such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6, which trigger hyperinflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Lung tissue samples of patients with COVID-19 showed complement-mediated severe thrombotic microvascular injury syndrome, with sustained activation of the alternative complement pathway29. More than 70 per cent of patients with severe COVID-19 meet the criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation30. Formation of thrombosis in coronary microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction are hypothesized as the causative mechanism of myocardial injury in severe COVID-19 patients121731. A recent study of 100 recovered COVID-19 patients who underwent cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealed cardiac involvement in 78 (78%) patients and ongoing inflammation in 60 (60%) patients9. Another autopsy study28 of 39 COVID-19 positive cases documented SARS-CoV-2 in myocardium in 24 of 39 (61.5%) cases28. Viral load of >1000 copies/μg RNA was documented in 16 of 39 (41%) cases. Higher levels of viral RNA were associated with higher cytokine levels, however this was not associated with an influx of inflammatory cells28.

- The proposed mechanism of cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19. Hyperinflammatory state secondary to cytokine storm, increased angiotensin II, low ACE2 levels and APLA contribute to thrombus formation in coronary and pulmonary vasculature. APLA, antiphospholipid antibodies; IL, interleukin; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Source: Refs 2425.

Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19

COVID-19 can have the following cardiovascular manifestations:

-

(i)

Myocardial infarction: COVID-19 can be a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) mimic. ACS could be due to plaque rupture, coronary artery spasm, supply-demand mismatch or endothelial dysfunction due to cytokine storm. In the initial report from Wuhan, China, up to 27.8 per cent COVID-19 patients had an elevated troponin level, indicating myocardial damage during the index hospitalization for COVID7. In a recent case series by Bangalore et al8, among 18 patients with COVID-19 having STEMI, nine (50%) patients underwent coronary angiography and five among these nine patients underwent percutaneous coronary angiography. The results showed a high prevalence of non-obstructive CAD, variable presentation and poor prognosis even after revascularization as 13 (72%) patients died in the hospital. In another series from Lombardy, Italy31, among 28 patients with STEMI, 17 (60.7%) had critical disease and 11 (39.3%) had non-obstructive CAD. Delayed presentation of ACS has been reported worldwide, and it has been perceived that some patients have died of ACS without seeking medical attention3233. The majority of these deaths can be attributed to serious arrhythmias, and mechanical complications leading to cardiogenic shock. In our earlier study, we analyzed the clinical characteristics and outcome in patients with a delayed presentation after STEMI and complicated by cardiogenic shock and showed that the in-hospital mortality was 42.9 per cent34. The American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention (SCAI) proposed specific guidelines regarding the management of ACS in the existing COVID-19 pandemic (Table)35.

-

(ii)

Myocarditis: The increase in troponin and NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide) levels reflects the myocardial injury caused by the SARS-CoV-27. A few cases of fulminant myocarditis have also been reported with COVID-197. Data are scarce on the cardiac imaging of COVID-19 patients. Echocardiography revealed severe left ventricle systolic dysfunction in anecdotal reports36. Cardiac MRI demonstrated marked biventricular myocardial interstitial oedema, along with diffuse late gadolinium enhancement involving the entire biventricular wall, suggestive of extensive myocardial injury37. In addition, myocarditis can manifest after complete resolution of symptoms as dilated cardiomyopathy, as seen in viral myocarditis.

-

(iii)

Heart failure: Patients with COVID-19 can have symptoms such as dyspnoea, palpitations and fatigue, which can be attributed to heart failure. In an initial study from China nearly 18.7 per cent of 1099 adult inpatients of COVID-19 had dyspnoea on initial presentation38. Acute heart failure ranges from 4.1 to 23 per cent in various studies, and it complicates the clinical course of COVID-19738. The acute heart failure can be due to myocardial ischaemia, myocarditis or tachyarrhythmia. It is difficult to differentiate the symptoms of acute heart failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome. Increasing level of cardiac troponins and NT-proBNP should raise suspicion regarding myocardial injury in COVID-19.

Patients with chronic heart failure are predisposed to COVID-19 due to advanced age and the presence of several comorbidities. There is a possibility of an increase in heart failure precipitations in the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients with chronic heart failure should remain compliant with their medications.

-

(iv)

Arrhythmias: The incidence of malignant arrhythmia was 5.9 per cent in an initial study of COVID-19 from China38. The worldwide cross-sectional survey reported benign to potentially life-threatening arrhythmias in the hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Atrial fibrillation followed by atrial flutter was the most commonly reported tachyarrhythmia, whereas severe sinus bradycardia was the most common bradyarrhythmia10. Arrhythmias can be the sequelae of hyperinflammation due to cytokine storm, myocarditis or drug-induced Torsades de Pointes (TdP). The high troponins were associated with the increased incidence of malignant arrhythmias, and mortality in the COVID-19 pandemic38. Though hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is a safe drug, it can precipitate TdP by prolonging the QT interval. Furthermore, the combination of HCQ and azithromycin increases the odds of TdP by prolonging QT interval, in patients who are already predisposed to arrhythmias39. A retrospective cohort study of 40 patients with COVID-19 showed that six (33%) of 18 patients developed an increase in QTc of ≥500 msec or greater on combination therapy (HCQ and azithromycin) versus one (5%) of 22 of those treated with HCQ alone (P=0.03), and there was no episode of TdP40. In a cohort of 90 hospitalized patients of COVID-19 reported by Mercuro et al41, 18 of the 90 patients (20%) treated with HCQ alone or in combination with azithromycin developed QTc prolongation of ≥500 msec or more, and one patient had TdP after stopping of drugs. The retrospective multicentric study by Rosenberg et al42 in 1438 COVID-19 patients on HCQ with and without azithromycin reported no association of HCQ with in-hospital mortality. In adjusted Coxproportional hazards models, compared with patients receiving neither drug, the mortality was not significantly differentfor patients receiving HCQ + azithromycin [hazard ratio (HR), 1.35], HCQ alone (HR, 1.08) or azithromycin alone (HR, 0.56)42. However, these studies were done in intensive care unit (ICU) settings with continuous monitoring of QTc, one is not certain about the implication of QTc prolongation in outpatients or non-ICU hospitalized patients, where continuous monitoring is not available.

-

(v)

Pulmonary embolism (PE): Recent studies engrossed on PE as a silent cause of mortality in the COVID-19 pneumonia. The cumulative incidence of PE was 20.6 and 23 per cent in two different case series from Italy4344. The PE was frequently present in segmental arteries of the pulmonary artery44. After acute respiratory distress syndrome and myocarditis, PE is the most common cause of mortality in patients with COVID-19. There is a plausible association between the hyperinflammatory state in COVID-19 and PE45. Moreover, the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies in some cases of COVID-19 pneumonia raises the suspicion of hypercoagulable state in COVID-1924. The symptoms and signs of PE are difficult to recognize in the COVID-19 pneumonia and create a delay in the diagnosis of PE. Acute worsening of hypoxia, hypotension and unexplained sinus tachycardia should alarm the diagnosis of PE. Echocardiography and CT pulmonary angiography could be performed after a complete evaluation of symptoms, and a strong suspicion of PE. D-dimers are usually raised due to the cytokine storm in COVID-19 and will not help in diagnosing PE25.

| All patient with ACS should be evaluated in the ED. Patients should wear a face mask and undergo COVID-19 testing in ED serial 12-lead ECG, transthoracic ECHO and portable chest X-ray for equivocal symptoms or non-specific ECG findings. The management of ACS is summarized below | |

| In PCI-capable hospitals | |

| Definitive STEMI (classical clinical symptoms and ECG consistent with STEMI) | Primary PCI remains the standard of care for patients presenting to PCI centres, if it can be done within 90 min of FMC |

| Possible STEMI (unclear clinical symptoms, equivocal, diffuse ST-segment elevation or delayed presentation) | Initial non-invasive evaluation in the form of ECHO for assessment of wall motion abnormality, and coronary CT angiography in cases of divergent findings in ECG and ECHO |

| NSTEMI/USA | Medical management. PCI should be offered in case of haemodynamic instability or high risk clinical features (GRACE score >140) |

| Patients with cardiogenic shock and/or OHCA | Patients with resuscitated OHCA or patients with cardiogenic shock should be subjected to coronary angiography in the presence of persistent ST-elevation in the ECG, and a concomitant wall motion abnormality on ECHO. Resuscitated OHCA in the absence of ST-elevation should be managed conservatively unless there is high suspicion of ACS |

| In non-PCI-capable hospitals | |

| Definite STEMI | Primary PCI remains the standard of care if patients can be transferred within 120 min of FMC from non-PCI centres to PCI-capable centres |

| Pharmacoinvasive approach with fibrinolysis followed by transfer to a PCI centre when necessary (failed thrombolysis, rescue PCI or haemodynamic instability) is also recommended. | |

| NSTEMI/USA | Medical management. PCI should be offered in case of haemodynamic instability or high risk clinical features (GRACE score >140) |

| Patients with cardiogenic shock and/or OHCA | Patients with resuscitated OHCA or patients with cardiogenic shock should be selectively considered for transfer to PCI-capable hospital in the presence of persistent ST-elevation in the ECG, and a concomitant wall motion abnormality on ECHO |

STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI; non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; USA, unstable angina; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; ED, emergency department; ECG, electrocardiogram; ECHO, echocardiogram; FMC, first medical contact; CT, computed tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Source: Ref. 35

Interaction between ACE2, COVID-19 and ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

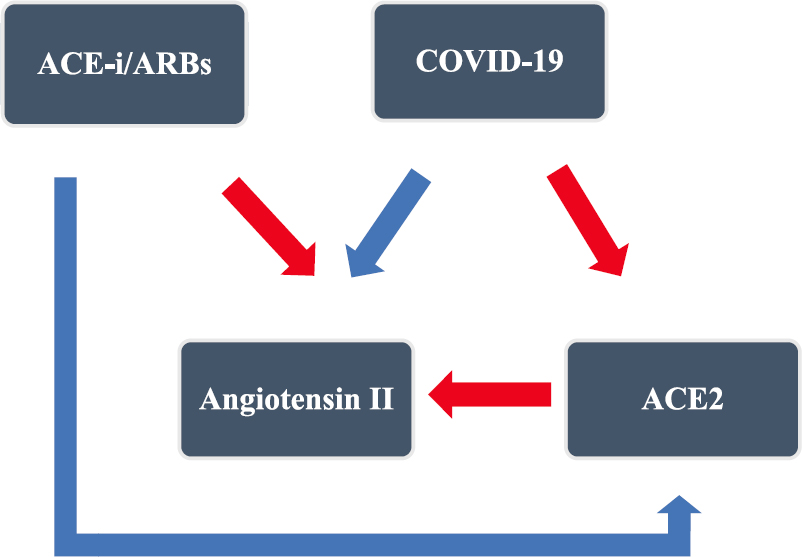

There is a complex relationship between ACE2, SARS-CoV-2 and ACE inhibitors/ARBs (Fig. 3). Theoretically, ACE inhibitors/ARBs increase ACE2 by upregulating mRNA levels in animal (rat) and human studies, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2, and might predisposes to viral entry into cell46474849505152. On the other hand, ACE inhibitors reduce angiotensin II levels by inhibiting ACE. Angiotensin II is involved in the inflammatory cascade of COVID-19 and reducingangiotensin II might benefit in COVID-19.

- Complex interaction of ACE-i/ARBs and COVID-19. In COVID-19, the virus downregulates ACE2, which acts as a receptor of SARS-CoV-2. The physiological function of ACE2 is to catalyze angiotensin II to angiotensin 1-7, and acts like a gatekeeper of the RAAS pathway. This leads to angiotensin surge in COVID-19. The ACE-i/ARBs inhibit RAAS pathway and upregulate the ACE2 level. Red arrows represent downregulation and blue arrows represent upregulation. ACE-i, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

After the report by Sommerstein and Gräni53, regarding the use of ACE inhibitors as a potential risk factor for fatal COVID-19, the potential beneficial and harmful effects of ACE inhibitors/ARBs have been debated in many studies. A population-based, case-control study of 6272 patients of SARS-CoV-2 in the Lombardy region of Italy showed no association of ACE inhibitors/ARBs with overall COVID-19 cases, or among patients who had a severe or fatal course of the disease [adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 0.83 for ARBs and 0.91 for ACE inhibitors], and no association between these variables was found with regard to sex54. Li et al55, in 362 patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, showed no association of ACE inhibitors/ARBs with mortality. The retrospective study by Zhang et al56 favoured the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs in COVID-19 patients hospitalized with hypertension and showed a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared with ACE inhibitors/ARBs non-users (adjusted HR, 0.37; P=0.03). In another retrospective analysis by Mehta et al57 among 18,472 patients tested for SARS-CoV-2, only 2285 patients (12.4%) were taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs, which again showed no association of ACE inhibitors/ARBs with COVID-19 positivity. These four studies together provide tentative evidence that ACE inhibitors/ARBs neither predispose nor are harmful in COVID-19 patients and accordingly, ACE inhibitors/ARBs should be continued in patients who are on these drugs for hypertension, heart failure or other clinical indications, as is recommended by various societies/guidelines58.

Treatment

The management of cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 is not standardized. Among the many antiviral drugs being tried for COVID-19, none has so far shown any significant benefit in critically ill patients16. In view of this, treatment mostly remains symptomatic. Nonetheless, a few points can be highlighted:

-

Among the repurposed drugs, the role of HCQ either alone or in combination with azithromycin in the treatment of COVID-19 is controversial59. Other antiviral drugs such as lopinavir-ritonavir, remdesivir and favipiravir have not shown any benefit on mortality. Remdesivir, however, showed a shorter duration to recovery60. The RECOVERY trial showed that the use of dexamethasone (6 mg) for up to 10 days vs. usual care decreased 28 days mortality among patients receiving oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation. No benefit was reported in patients who were not on any respiratory support61. There is not enough evidence for the usage of these drugs in cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19.

-

Healthcare workers (HCW) should take stringent precautions to prevent themselves from getting infected. A study by Chatterjee et al62 reported that HCQ prophylaxis after four or more maintenance doses significantly reduced the odds of getting infected (AOR: 0.44; 95%). Use of personal protective equipment was associated with reduction in the odds of contracting COVID-1962.

-

The use of investigations such as echocardiography and troponins, as routine, in patients with COVID-19 should be avoided63. However, when clinically indicated, these investigations may help in the diagnosis, management and prognosis of cardiovascular involvement.

-

Management of STEMI cannot be delayed, waiting for the result of COVID-19. If feasible, a dedicated COVID-19 catheterization laboratory is preferable356465. The need is to protect HCWs from contracting the infection from a suspected COVID-19 patient. A summary of the guidelines given by AHA/ACC/SCAI for management of ACS is presented in the Table and Figure 4 35.

-

Patients with acute decompensated heart failure should be managed according to the standard guidelines. Low threshold should be kept for early or elective intubation in patients with respiratory distress, to avoid the aerosolization associated with emergency intubation. Guideline-directed medical therapy should be continued and, in patients taking ACE inhibitors/ARBs, it should be continued. In treatment-naïve COVID-19 patients, guidelines are unclear regarding the starting of ACE inhibitors/ARBs67.

-

Arrhythmias should be managed as per standard guidelines. Risk-benefit assessment should be done and non-urgent procedures should be postponed and refractory/life-threatening arrhythmias not controlled on medical therapy should be undertaken for electrophysiological study68.

![Management of STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic. ECG, electrocardiography; PPE, personal protective equipment. Source: Ref. 35. [Case classification: COVID-19 positive: any person meeting the laboratory criteria (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction positive for SARS-CoV-2); COVID-19 possible: any person meeting the clinical criteria (cough, fever, shortness of breath and sudden onset of anosmia, ageusia or dysgeusia) and COVID-19 probable case: any person meeting the clinical criteria with an epidemiological link or any person meeting the diagnostic criteria]66.](/content/175/2021/153/1-2/img/IJMR-153-7-g004.png)

- Management of STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic. ECG, electrocardiography; PPE, personal protective equipment. Source: Ref. 35. [Case classification: COVID-19 positive: any person meeting the laboratory criteria (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction positive for SARS-CoV-2); COVID-19 possible: any person meeting the clinical criteria (cough, fever, shortness of breath and sudden onset of anosmia, ageusia or dysgeusia) and COVID-19 probable case: any person meeting the clinical criteria with an epidemiological link or any person meeting the diagnostic criteria]66.

Conclusion

The extent of the spread of COVID-19 is such that despite being predominantly a respiratory disease, many patients are having cardiovascular involvement. Not only patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases and risk factors are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19, but also these patients may directly present with cardiovascular complications such as myocardial infarction, myocarditis, heart failure, arrhythmias or PE. Various gaps in research include the evidence-based management of various cardiovascular complications, care of chronic patients with cardiovascular issues not suffering from COVID-19 and the ethical challenges in triage of these patients. Worldwide efforts are presently on to find antiviral drugs and vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. The need of the hour is to manage these patients with the best evidence-based guidelines and to be on the cognizant of the new emerging data on a day-to-day basis.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

- A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- COVID-19 India (updated 1 June 2020). Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in

- Association of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:751-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- ST-segment elevation in patients with COVID-19 - A case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2478-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1265-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 and cardiac arrhythmias: A global perspective on arrhythmia characteristics and management strategies. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2020;59:329-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lombardia CARe researchers.Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:496-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: A review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:831-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The science underlying COVID-19: Implications for the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2020;142:68-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271-80. e8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1653-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-demographic profile & hospital outcomes of COVID-19 patients admitted at a tertiary care centre in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2020;152:61-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute pulmonary embolism: An unseen villain in COVID-19. Indian Heart J. 2020;72:218-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- SARS-coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:618-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial localization of coronavirus in COVID-19 cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22:911-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of cardiac infection with SARS-CoV-2 in confirmed COVID-19 autopsy cases. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1281-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: A report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19: Clinical and angiographic outcomes. Circulation. 2020;141:2113-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong, China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006631.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:88-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics and outcome in patients with a delayed presentation after ST-elevation myocardial infarction and complicated by cardiogenic shock. Indian Heart J. 2019;71:387-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: From the ACC's interventional council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus fulminant myocarditis saved with glucocorticoid and human immunoglobulin. Eur Heart J 2020:ehaa190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:819-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:811-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Cardiotoxicity of Antimalarials: World Health Organization Malaria Policy Advisory Committee Meeting. Available from: https://www.who.int/malaria/mpac/mpac-mar2017-erg-cardiotoxicityreport-session2.pdf

- Assessment of QT intervals in a case series of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection treated with hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin in an intensive care unit. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1067-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1036-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA. 2020;323:2493-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute pulmonary embolism associated with COVID-19 pneumonia detected with pulmonary CT angiography. Radiology. 2020;296:E186-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: Awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142:184-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: A random association? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1858.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Olmesartan attenuates the development of heart failure after experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats through the modulation of ANG 1-7 mas receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351:208-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Olmesartan medoxomil treatment potently improves cardiac myosin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy via the modulation of ACE-2 and ANG 1-7 mas receptor. Free Radic Res. 2012;46:850-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combination renin-angiotensin system blockade and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in experimental myocardial infarction: Implications for future therapeutic directions. Clin Sci (Lond). 2012;123:649-58.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence against a major role for angiotensin converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) in angiotensin peptide metabolism in the human coronary circulation. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1971-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in hypertensive patients may be increased by olmesartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:15-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in human heart failure: Relation with myocardial function and clinical outcomes. J Card Fail. 2009;15:565-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid response: Re: Preventing a COVID-19 pandemic: ACE inhibitors as a potential risk factor for fatal COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;368:m810.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2431-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:825-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of inpatient use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020;126:1671-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1020-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continue ACE inhibitors/ARB'S till further evidence in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Indian Heart J. 2020;72:212-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydroxychloroquine with or without Azithromycin in mild-to-moderate COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2041-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 - Preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020 NEJMoa2021436

- [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare workers & SARS-CoV-2 infection in India: A case-control investigation in the time of COVID-19. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:459-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- ASE statement on protection of patients and echocardiography service providers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3078-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESC guidance for the diagnosis and management of CV disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available from: https://www.escardio.org/Education/COVID-19-and-Cardiology/ESC-COVID-19-Guidance

- Management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;96:336-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case definition for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), as of 29 May 2020. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/surveillance/case-definition

- Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:e233-e241.

- [Google Scholar]