Translate this page into:

Barriers to treatment-seeking for impairment of vision among elderly persons in a resettlement colony of Delhi: A population-based cross-sectional study

For correspondence: Dr Sanjeev Kumar Gupta, Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: sgupta_91@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Uncorrected refractive error and cataract are the two most common causes of impairment of vision among elderly persons, and both are treatable. Treatment-seeking in patients is driven by symptom (decreased vision) rather than any anatomical or physiological measurement. The objective of this study was to evaluate the treatment-seeking behavior and barriers to treatment-seeking among elderly persons with impairment of vision in an urban resettlement colony of New Delhi, India.

Methods:

This community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted among 604 persons aged ≥60 yr selected by the simple random sampling. House-to-house visit was done, and a self-developed pretested semi-structured interview schedule was used to collect socio-demographic information, treatment-seeking behaviour and barriers to treatment-seeking.

Results:

Majority of participants reported impairment of vision (84%); 16.5 per cent of them did not visit any healthcare facility for their vision problem. Lack of felt need (48.1%) was the most common barrier to visiting healthcare facility. Of the 401 participants who gave a history of being prescribed spectacles, 277 (69%) used spectacles. Discomfort, lack of improvement in vision and lack of felt need were the most common reasons cited for non-usage. Among 300 participants who gave a history of cataract, 61 (20.3%) had not undergone cataract surgery. Lack of felt need was the most common barrier to cataract surgery.

Interpretation & conclusions:

A substantial proportion of elderly persons in the urban community have impairment of vision. Lack of felt need was the main reason for not visiting healthcare facility. As quality of spectacles was an important reported deterrent to use of spectacles, provision of appropriate refraction services and low-cost, good quality spectacles would be important.

Keywords

Barriers

cataract

elderly

impairment of vision

spectacles - treatment-seeking

Globally, an estimated 2.2 billion people live with some form of distant or near vision impairment. About 50 per cent of visual impairment is avoidable, namely treatable or preventable. Among the 253 million with distant vision impairment, 36 million are blind, 217 million have visual impairment1. Most of the visually impaired people are aged 50 yr and above2. In India, prevalence of visual impairment is estimated to be 2.55 per cent of total population3. Treatment-seeking is largely related to the difficulty a person faces in performing various functions and routine activities, rather than the objective measurement of visual acuity. Impairment of vision is related to quality of life, social activities and activities of daily living, independence and economic productivity. In view of the demographic transition and population ageing, the burden of eye diseases can be expected to rise in the near future. Therefore, along with provision of services, barriers to uptake of services have to be understood to promptly investigate and treat impairment of vision, in order to decrease the burden of the same.

Cataract and uncorrected refractive errors are the two most common causes of impairment of vision among elderly persons4, and both are treatable. Cataract is a degenerative condition of the lens, which is easily treatable with surgery. Guidelines are available for indications and contraindications of cataract surgery5. It is not enough to focus on cataract surgery rate and uptake of cataract surgical services67. The barriers to treatment-seeking among elderly persons previously diagnosed with cataract are poorly understood in the urban context and also need to be studied8910. Population-based studies conducted in the last two decades in India show that uncorrected refractive errors are the leading cause of visual impairment1112. While uncorrected refractive errors can be corrected using spectacles, several barriers limit the uptake of services.

A variety of reasons, including dependence on caregivers (both financial and otherwise, financial constraints), distant location of healthcare facilities, lack of awareness about the problem and location of healthcare facilities, fear of surgery and lack of felt need affect the treatment-seeking behaviour in the elderly population13. However, most of these studies for treatment-seeking behaviour are conducted on persons with visual impairment, rather than those who report impairment of vision. Standard definition of visual impairment is used14, which does not include self-reported impairment of vision.

This research was conducted to study the treatment-seeking behaviour and related barriers among elderly persons who reported impairment of vision in a resettlement colony of New Delhi, India. The objectives of this study were to estimate the proportion of persons not utilizing healthcare services for impairment of vision, and barriers to utilize them; proportion of persons not using spectacles despite being advised, and barriers to using spectacles; and proportion of persons who had not undergone cataract surgery after being advised, and barriers to undergo cataract surgery in them.

Material & Methods

This was a community-based, cross-sectional study carried out among persons aged 60 yr and above living in Dakshinpuri Extension, an urban resettlement colony in New Delhi, India. The study was conducted by the Centre for Community Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants. Those who required eye care services were referred to the nearest healthcare facility. Demographic information on all individuals was available in a Health Management Information System (HMIS), which is updated regularly. This source was used to provide the sampling frame. There were 2715 elderly persons in the study area. Data were collected during May and June 2017.

Marmamula et al1213 in their studies showed that 32 per cent of elderly persons did not utilize eye care services. Alpha error of 0.05 was considered and four per cent absolute error was taken. Non-response of 10 per cent, and death and migration rate of 7.5 per cent were considered for estimating final sample size. Final sample size was calculated as 604 elderly persons.

The participants were selected by simple random sampling from an urban resettlement colony in Dakshinpuri Extension from the HMIS data. Eligibility criteria included persons aged ≥60 yr residing in the study area for more than six months. Those with subnormal mental status were excluded from the study.

Procedure: House-to-house visits were done to contact the participants. Of the 604 participants selected, 555 (91.9%) were interviewed by the interviewer using a self-developed pre-tested semi-structured interview schedule which contained 25 items. The questionnaire was pre-tested in the hospital and primary eye care clinics involving individuals aged 60 yr and older. Socio-demographic information and data on selected self-reported chronic conditions were collected. The selected self-reported chronic conditions included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic respiratory diseases and joint pains. Participants were asked whether they had any impairment of vision, followed by whether they had sought treatment from any healthcare service provider for this difficulty. From those who did not seek any treatment, reasons were elicited using semi-structured interview schedule.

Subsequently, all participants were asked whether they were ever prescribed spectacles. In those who were prescribed, spectacle usage was asked. Among those who did not use spectacles inspite of being prescribed, reasons for not using them were recorded. All participants were asked whether they were ever diagnosed. If they were diagnosed with cataract, and had not undergone cataract surgery, reasons for not undergoing were recorded.

Outcome variables: Non-utilization of healthcare services despite having impairment of vision was taken as outcome. Other outcomes were non-usage of spectacles in spite of being prescribed spectacles, and not undergoing cataract surgery in those who were previously diagnosed with cataract.

Statistical analysis: Data were entered in Microsoft Excel version 2013 and analyzed in Stata version 12 (College station, Texas, USA)15. Data are presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)] and number (%). Outcome variables are reported as proportions (95% CI). The Chi-square test was used to test the differences in the outcome variables with gender. To see gender preferences for visiting healthcare services, significance in difference of proportions between two genders was tested using N-1 Chi-square test16 Multivariable logistic regression was used to find any association between the socio-demographic variables and non-utilization of healthcare facility. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were reported with the corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals (CIs) and P values.

Results

Of the randomly selected 604 elderly participants, 27 refused to participate and 22 could not be contacted despite three visits, including one on a weekend. Among those who refused, there were eight men and 19 women. Among those who could not be contacted, 17 were men and five were women. Finally, 555 participants were interviewed. The response rate was 91.9 per cent. The proportion (95% CI) of elderly persons with impairment of vision was 84 (81, 87) per cent. The mean age of participants was 67.9 ± 6.1 yr. The mean age for men was 67.7 ± 5.9 yr and for women, it was 67.9 ± 6.3 yr. Socio-demographic characteristics are reported in Table I. Among the participants, one person was never married (single), who was combined with widow/widower for further analyses. Majority had difficulty in both near vision and far vision (n=402, 86.3%). Among the rest, 49 had only near vision difficulty (10.5%) and 15 had only distant vision difficulty (3.2%).

| Variables | Number | Persons with impairment of vision (n=466), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age-categories (yr) | ||

| 60-64 | 167 | 132 (79.0) |

| 65-69 | 188 | 156 (83.0) |

| 70-74 | 103 | 87 (84.5) |

| 75 and more | 97 | 91 (93.8) |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 262 | 212 (80.9) |

| Women | 293 | 254 (86.7) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single (never married) | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Married | 320 | 261 (81.6) |

| Widow/widower | 234 | 204 (87.2) |

| Living status | ||

| Living alone | 33 | 29 (87.9) |

| Living with spouse only | 131 | 107 (81.7) |

| Living with spouse and children | 178 | 145 (81.5) |

| Living with only children | 201 | 177 (88.1) |

| Living with other family members | 12 | 8 (66.7) |

| Number of family members | ||

| 1-3 | 202 | 166 (82.2) |

| 4-6 | 210 | 177 (84.3) |

| 7 or more | 143 | 123 (86.0) |

| Type of family | ||

| Nuclear family | 195 | 160 (82.1) |

| Extended family | 360 | 306 (85.0) |

| Educational status | ||

| Illiterate | 294 | 254 (86.4) |

| Upto 5th standard | 134 | 112 (83.6) |

| 6th to 10th standard | 73 | 57 (78.1) |

| Above 10th standard | 54 | 43 (79.6) |

| Economic dependence | ||

| Independent | 192 | 152 (79.2) |

| Partially dependent | 261 | 226 (86.6) |

| Dependent | 102 | 88 (86.3) |

| Working status | ||

| Not working | 311 | 268 (86.2) |

| Working | 244 | 198 (81.1) |

| Number of selected self-reported chronic illness | ||

| None | 106 | 87 (82.1) |

| One | 182 | 142 (78.0) |

| Two | 174 | 153 (87.3) |

| Three or more | 93 | 84 (90.3) |

There were 466 participants (212 men, 254 women) who had impairment of vision. Among them, 77 (35 men, 42 women) participants (16.5%, 95% CI: 13-20) had not visited any health facility. The remaining177 (83.5%) men and 212 (83.5%) women visited healthcare facility. In those with impairment of vision, 248 (48.3%) participants visited private facility, while 181 (38.8%) visited government facility. Healthcare facility visited was not significantly different for both gender for private (P=0.11) and government health facility (P=0.79). Visits to multiple health facilities by single participants were possible.

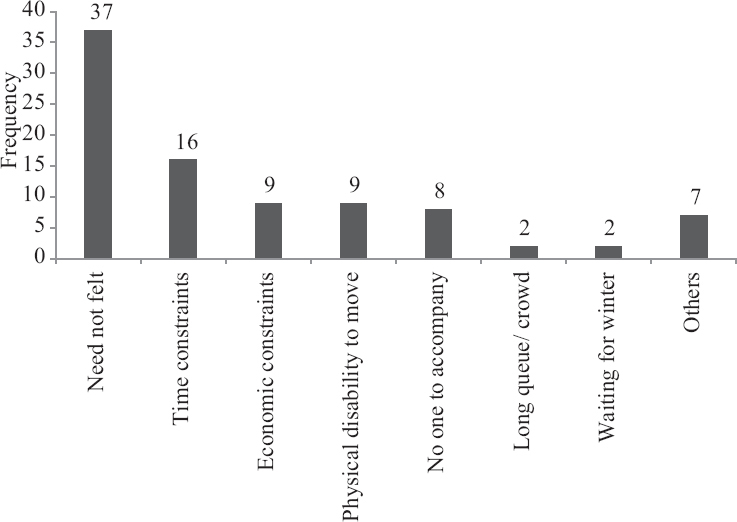

The most common reason cited for not visiting any healthcare facility was lack of felt need (48.1%) followed by time constraints (20.8%) (Fig. 1). Other reasons for not visiting healthcare facility included economic constraints, no one to accompany, waiting for winter, etc. None of the socio-demographic variables, including presence of comorbid systemic diseases were significantly associated with not visiting healthcare facilities among participants impairment of vision (Table II). Of the 555 participants, 401 were prescribed spectacles, and of these, 277 (69%) were using them. Among those using spectacles, three-fourths of participants felt that their vision improved after wearing spectacles (Table III).

- Barriers to visiting any healthcare facility by participants (n=77). (Multiple responses possible).

| Variables | Numbers | Not visiting healthcare facility (n=77), n (%) | Crude OR* (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR** (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories (yr) | ||||||

| 60-64 | 132 | 23 (17.4) | Reference | |||

| 65-69 | 156 | 25 (16.0) | 0.90 (0.49-1.68) | 0.75 | 0.94 (0.50-1.77) | 0.82 |

| 70-74 | 87 | 10 (11.5) | 0.61 (0.28-1.37) | 0.23 | 0.63 (0.27-1.42) | 0.27 |

| 75 and more | 91 | 19 (20.9) | 1.25 (0.63-2.46) | 0.51 | 1.39 (0.69-2.80) | 0.36 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 212 | 35 (16.5) | Reference | |||

| Women | 254 | 42 (16.5) | 1.00 (0.61-1.64) | 0.99 | - | - |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 261 | 44 (13.8) | Reference | |||

| Widow/widower | 205 | 33 (14.0) | 0.95 (0.58-1.56) | 0.84 | - | - |

| Living status | ||||||

| With spouse only | 107 | 21 (19.6) | Reference | |||

| With spouse and children | 145 | 21 (14.5) | 0.69 (0.36-1.34) | 0.28 | - | - |

| Only with children | 185 | 29 (15.7) | 0.76 (0.41-1.40) | 0.39 | - | - |

| Living alone | 29 | 6 (20.7) | 1.06 (0.39-2.95) | 0.90 | - | - |

| Type of family | ||||||

| Nuclear | 160 | 29 (18.1) | Reference | |||

| Extended | 306 | 48 (15.7) | 0.84 (0.50-1.39) | 0.50 | - | - |

| Number of family members | ||||||

| 1-3 | 166 | 30 (18.1) | Reference | |||

| 4-6 | 177 | 32 (18.1) | 1.00 (0.58-1.73) | 0.99 | 1.00 (0.57-1.78) | 0.98 |

| 7 or more | 123 | 15 (12.2) | 0.63 (0.32-1.23) | 0.17 | 0.66 (0.33-1.31) | 0.23 |

| Educational status | ||||||

| Above 10th standard | 43 | 6 (13.9) | Reference | |||

| 6th to 10th standard | 57 | 8 (14.0) | 1.00 (0.54-3.42) | 0.51 | - | - |

| Up to 5th standard | 112 | 17 (15.2) | 1.10 (0.40-3.01) | 0.85 | - | - |

| Illiterate | 254 | 46 (18.1) | 1.36 (0.32-3.15) | 0.99 | - | - |

| Economic dependence | ||||||

| Independent | 152 | 26 (17.1) | Reference | |||

| Partially dependent | 226 | 30 (13.3) | 0.74 (0.42-1.31) | 0.30 | 0.74 (0.41-1.35) | 0.32 |

| Dependent | 88 | 21 (23.9) | 1.52 (0.79-2.90) | 0.20 | 1.52 (0.79-2.95) | 0.21 |

| Working status | ||||||

| Working | 198 | 31 (15.6) | Reference | |||

| Not working | 268 | 46 (17.2) | 1.11 (0.68-1.83) | 0.66 | - | - |

| Number of selected self-reported chronic conditions | ||||||

| None | 87 | 18 (20.7) | Reference | |||

| One | 142 | 21 (14.8) | 0.66 (0.33-1.33) | 0.25 | 0.68 (0.34-1.39) | 0.29 |

| Two | 153 | 23 (15.0) | 0.67 (0.34-1.34) | 0.26 | 0.71 (0.35-1.42) | 0.34 |

| Three or more | 84 | 15 (17.8) | 0.83 (0.39-1.78) | 0.63 | 0.84 (0.38-1.83) | 0.66 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. * Crude OR calculated by bivariable logistic regression model; ** Variables with P≤0.25 were put in multivariable regression model. However, none of the variables were significant.

| Factor | Men (n=262), n (%) | Women (n=293), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Status of spectacle usage | ||

| Prescribed spectacles | 179 (68.3) | 222 (77.8)* |

| Using spectacles routinely | 133 (74.3) | 144 (64.9)* |

| Self-improvement in vision | 106 (79.7) | 106 (74.1) |

| Utilization of cataract surgical services† | ||

| Self-reported cataract | 129 (49.2) | 171 (58.4)* |

| Underwent cataract surgery | 105 (82.4) | 134 (78.4) |

| Satisfied with surgery | 78 (74.3) | 98 (73.1) |

*P<0.05 compared to men. †28 persons had bilateral cataract, but underwent cataract surgery in only one eye. Rest 61 did not go for cataract surgery. Percentages are successive, with denominator being the number of persons in previous row, in the same column

The most common reasons cited for not wearing spectacles were spectacles not comfortable, followed by no improvement seen on wearing spectacles, need not felt financial reasons and others. Other reasons included ashamed of spectacles, waiting for shopkeeper to make spectacles, waiting for cataract surgery before making spectacles, do not want to develop habit of wearing spectacles, redness of eyes and unaware of eye problem.

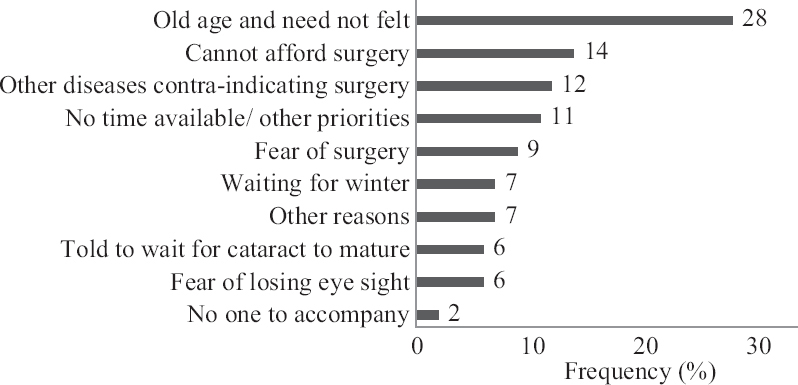

More than half the participants had been previously diagnosed with cataract, and among these, four-fifths had undergone surgery in at least one eye. Most of the participants (73.8%) were satisfied with the operation (Table III). Lack of felt need was most common barrier for undergoing cataract surgery (Fig. 2).

- Barriers to undergoing cataract surgery (n=89) (Multiple responses possible).

Discussion

In our study setting, elderly persons require someone to accompany them to healthcare facilities. This is reflected in our study also. The old age group, less family members and participants living with only their spouse were more likely not to visit healthcare facility. It was observed that a high proportion of illiterate elderly persons did not visit healthcare facilities. Lack of felt need was a major barrier. Felt need is a subjective phenomenon. People with impairment of vision may still be able to perform their day-to-day activities, and functions based on vision, such as, navigating inside and outside home, identifying people from far and near, walking up and down the stairs, locking and unlocking doors, searching small objects, etc. Lack of perceived need was also the most common cause in earlier studies1317 from Andhra Pradesh. Another study conducted by Marmamula et al18 in Prakasam district also found old age and no felt need as important barriers to eye-care service utilization. However, these studies were conducted predominantly in rural areas.

Discomfort and lack of improvement in vision on using spectacles were the main barriers for not using spectacles. Adequate correction by refraction and good quality of spectacles may help in overcoming these barriers. Lack of felt need and financial reasons were also important barriers. Similar results were found by a study by Senjam et al11 from Delhi, wherein common reasons for not using spectacles included lack of felt need (31.5%), unable to afford (16.2%), uncomfortable to wear (16.2%) among others. The proportion of lack of felt need was higher in this study because the age group was ≥40 yr, and because the denominator was number of persons with improvement in pin-hole visual acuity rather than impairment of vision. This may be because patients with refractive error would first accommodate with symptoms before seeking treatment; and seek treatment only when the symptoms become more severe1920.

Patil et al21 from Sindhudurg, Maharashtra, reported barriers to cataract surgery in individuals to be non-affordability (22.1%), unaware of cataract (20.0%) and no felt need (13.2%). Thoufeeq et al22 from Maldives found that the barriers to cataract surgery uptake were lack of felt need (29.7%), deference of treatment by health providers (33.3%) and fear of surgery (12.3%) among others. Lack of felt need rather than unaffordability was the main barrier in our study because many different government and non-governmental organizations were involved in providing cataract surgery at low cost in our study.

This was a community-based study with high response rate (91.9%). Hence, the results may be generalizable to urban resettlement colonies. Since it was a cross-sectional study, causality could not be interpreted for not utilizing healthcare services. Furthermore, qualitative research methods would have added more insight about the barriers but are more resource-intensive and time-consuming.

Majority of participants with impairment of vision visited some healthcare facility. Among those who did not avail any service, lack of felt need was the most common reason. Benefits of resolving the impairment of vision may be highlighted to them to address this barrier. None of the socio-demographic variables were significantly associated with not visiting health facility. During health education programmes in the community, benefits of improvement in vision by use of spectacles and cataract surgery need to be highlighted. Prescription of spectacles by competent staff, and availability of affordable, good quality spectacles for elderly persons need to be ensured. Qualitative research methods may be used in further studies on this subject.

Financial support & sponsorship: None.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- Blindness and vision impairment. Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnitude, temporal trends, and projections of the global prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e888-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Programme for Prevention of Blindness &Visual Impairment, Directorate General of Health Services. Ministry of Health &Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi. National blindness and visual impairment survey India 2015-2019. Available from:https://npcbvi.gov.in/writereaddata/mainlinkfile/fil|ne341.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990-2020:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e1221-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- VISION 2020:The Right to Sight India. Guidelines for the Management of Cataract in India. Available from:https://www.sightsaversindia.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/16480_Cataract_Manual_VISION2020.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of cataract surgical coverage in India:Findings from a population-based study. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4:320-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving cataract services in the Indian context. Community Eye Health. 2014;27:4-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coverage, utilization and barriers to cataract surgical services in rural South India:Results from a population-based study. Public Health. 2007;121:130-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to uptake of referral services from secondary care to tertiary care and its associated factors in L V Prasad Eye Institute network in Southern India:A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020687.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors limiting the Northeast Indian elderly population from seeking cataract surgical treatment:Evidence from Kolasib district, Mizoram, India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:969-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive error:Results from Delhi-rapid assessment of visual impairment study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2016;64:387-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual impairment in the South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh:Andhra Pradesh - Rapid assessment of visual impairment (AP-RAVI) project. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70120.

- [Google Scholar]

- A population-based cross-sectional study of barriers to uptake of eye care services in South India:The rapid assessment of visual impairment (RAVI) project. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005125.

- [Google Scholar]

- ICD-10 Version:2016. Available from:http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/H53-H54

- [Google Scholar]

- 2 ×2 Tables:a note on Campbell's recommendation. Statistics in Med. 2016;35:1354-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to accessing eye care services among visually impaired populations in rural Andhra Pradesh, South India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:365-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visual impairment among weaving communities in Prakasam district in South India. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55924.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utilisation of eyecare services in an urban population in southern India:The Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:22-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Where do persons with blindness caused by cataracts in rural areas of India seek treatment and why? Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:1337-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, causes of blindness, visual impairment and cataract surgical services in Sindhudurg district on the western coastal strip of India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:240-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- First rapid assessment of avoidable blindness survey in the Maldives:Prevalence and causes of blindness and cataract surgery. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol. 2018;7:316-20.

- [Google Scholar]