Translate this page into:

Awareness & perceptions about organ donation among patient attendants in a tertiary-care hospital in South India: An observational study

For correspondence: Dr Nachiket Shankar, Department of Anatomy, St. John’s Medical College, Koramangala, Bangalore 560 034, Karnataka, India e-mail: nachiket.s@stjohns.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

Abstract

Background & objectives

Numerous barriers like lack of awareness, fear of misuse and sociocultural beliefs contribute towards low rates of organ donation. In 2019, India had a donation rate of only 0.52 per million. Hence, this study was undertaken to determine the awareness levels and perceptions about organ donation among patient attendants in a tertiary-care hospital in South India.

Methods

This cross-sectional study, ‘passing on the torch of life’, with a sample size of 110 was conducted in a tertiary care hospital from June to October 2022. Beds across were selected by simple random sampling and the attendants of patients were interviewed using a face-validated structured interview schedule. Data was analysed using SPSS v.20 using the independent sample t test and ANOVA.

Results

The majority of the participants were Hindus (62%), married (68%), living in urban areas (62%) and gainfully employed (60%). The mean awareness score was 7.86±2.64 (out of 13). About 70 per cent of the participants were regarded to have adequate knowledge. The mean perception score was 67±9.41 (out of 86). A total of 95 per cent of the participants supported organ donation, however only 51 per cent were willing to donate. Males, participants with higher education and income and those residing in urban areas had significantly higher awareness scores (P<0.05). Multiple linear regression analysis showed that higher education levels was a predictor of increased awareness (P=0.036).

Interpretation & conclusions

The majority of participants had adequate awareness, positive perceptions and supported organ donation, however, only 51 per cent were willing to donate their organs. Education levels was a significant predictor of awareness levels. A further qualitative study is recommended to explore the reasons behind the unwillingness to donate, despite strong support for organ donation.

Keywords

Awareness

barriers

deceased donation

living donation

organ donation

perception

Organ transplantation is a key medical milestone, yet there’s a large gap between organ demand and supply in India. In 2019, India’s donation rate was only 0.52 per million people, compared to 46.9 in Spain and 36.8 in the United States of America1. Though deceased organ donation rates in India increased from 0.27 to 0.52 per million between 2013 and 2019, these donations account for less than 20 per cent of all organ donations (deceased and living donations)2. Many potential donors are brain-dead victims of traffic accidents. In 2019 alone, there were 1,37,689 deaths nationally due to road traffic accidents and a previous study estimated around 68.7 per cent of road traffic accident victims in India to have fatal traumatic brain injuries3,4. Hence, in 2019, 94,592 individuals were potential donors, yet only 715 donations occurred2. Moreover, post the COVID-19 pandemic, global organ donations have declined by 17.6 per cent5,6.

One of the key barriers to organ donation is the lack of awareness among the general population7. Other factors include sociocultural aspects such as superstitions and religious beliefs, lack of familial consent, fear of misuse and misconceptions about the organ donation process7-9. In terms of organizational barriers, poor levels of coordination and poor communication within the teams involved in organ donation and inadequate counselling of the key stakeholders were the key barriers. These in turn lead to the low rates of deceased donation rates seen in India. Hence it is important to assess the knowledge levels and views on organ donation to help understand the current barriers.

While there have been many Indian studies on medical professionals10, students in the healthcare profession11, specific demographic groups like police personnel12, rural communities13 and patients14 there is limited data on the knowledge levels and perceptions of the general public. A study done in 2016, showed that only 52.8 per cent of the general population have adequate awareness on organ donation15. Therefore, this study was undertaken to explore the current knowledge levels and perceptions about organ donation by interviewing patient attendants in a tertiary care hospital in a metropolitan city in South India using a structured interview schedule. The medical college hospital in which the study was undertaken caters to patients from various socioeconomic strata, hence the attenders of patients are likely to be a representative of the general public in the study area.

Materials & Methods

This study was conducted at the department of Anatomy, St John’s Medical College, Bangalore after obtaining the ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Data was collected by face-to-face interview after taking written informed consent or thumbprints for illiterate individuals.

Study area, design and population

This cross-sectional study was conducted from May to November 2022 at a 1,350-bed tertiary care hospital in Bangalore, Karnataka. The study population were attendants of inpatients, aged 18 yr or older, interviewed using a pre-validated schedule. The study excluded individuals with cognitive impairments and attendants in the Intensive Trauma Units or Intensive Care Units, emergency, and COVID wards.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated by using the formula

Where n was the sample size and Zα was 1.96. The estimated prevalence, p was taken as 52.8 from a previous study done in India that showed 52.8 per cent of the participants had adequate knowledge about organ donation15. Subsequently, q (100 – p) was taken as 47.2 along with a desired level of precision (d) of 10 per cent. Hence, the sample size was calculated to be 96, which was rounded off to 100. After allowing for 10 per cent of the interviews to be incomplete, the final sample size was estimated to be 110.

Sampling plan

A simple random sampling method was used. Bed numbers meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were mapped, and 875 beds were identified as part of the sampling frame. Random numbers generated by SPSS v.20 selected the beds, and the attendant of the chosen bed was interviewed. If the attendant did not consent or the bed was empty, the next available bed in sequence was selected.

Study tool

The study used a pretested, face-validated interview schedule. It was validated by five experts working in community medicine, forensic medicine, medical social work, and medical humanities. It consisted of three sections (A, B, and C) with questions based on two previous studies done in India and the US respectively15,16. The two studies were chosen for their comprehensive questionnaires. The tool aimed to collect data about the variables of interest: knowledge and perceptions of organ donation (the dependent variables) and the sociodemographic factors (the independent variables). The tool was translated into five local languages (Kannada, Hindi, Telugu, Malayalam, Tamil) and back-translated for accuracy. It was pretested with 15 patient attendants. The study tool has been included as a supplementary material.

Section A

Sociodemographic details: There were 11 questions on sociodemographic details such as age, gender, religion, educational background, economic status and place of residence.

Section B

Awareness on organ donation: This section included 13 questions to assess awareness: eight on general organ donation and five on donation laws. Each correct answer earned one point, with a maximum score of 13. A score of ≥50 per cent indicated adequate awareness of organ donation.

Section C

Attitude on organ donation: Section C consisted of 26 questions focused on participants’ willingness to donate organs and their perspectives on organ donation. Most questions had responses recorded using a 5-point Likert scale. There was one open-ended question (question 16) to explore reasons for unwillingness. All questions except question 15 was scored out of 5 while question 15 scored out of 1. Questions 2-4, 9-12, and 16 were excluded from final scoring, they were kept to better understand perceptions. Hence, this led to a total score of 86 points, with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes. All negatively worded items were reverse-coded before analysis.

Data analysis

The data collected was entered into a MS Excel sheet, then analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) v.2017. Participants scoring ≥50 per cent of the score range of the section B were regarded to have adequate knowledge or awareness. Awareness and perception scores obtained from sections B and C, respectively were the primary outcome variables. The secondary objective of the association of awareness levels with sociodemographic variables was assessed using the independent sample t test and ANOVA. Multiple linear regression was done to estimate associations if any between sociodemographic variables and the previously stated outcome variable. A P value of <0.05 was considered as significant. Additionally, thematic analysis was done on a question in section C to find reasons behind unwillingness to donate.

Results

Out of 110 patient attendants interviewed, nine interviews were incomplete, and one withdrew consent, leaving 100 participants for analysis. The participants included 55 females and 45 males, with ages ranging from 19 to 66 yr (mean age 35.1±10.8). Most were Hindus (62%), married (68%), living in urban areas (62%), and employed (60%).

The mean awareness score was 7.86±2.64 (out of 13). Seventy per cent (n=70) had adequate knowledge, while 30 per cent (n=30) had inadequate knowledge. Ninety-five per cent had heard of organ donation, with mass media being the primary source of awareness for 79 per cent of participants (Table I).

| Source | f (n=100) |

|---|---|

| Mass media | 79 |

| Discussion with a family member/friend | 36 |

| Information provided by medical personnel | 23 |

| Social media | 23 |

| Health awareness camp | 16 |

| Personal experience or involvement | 8 |

| Billboard or poster | 8 |

| Schools and textbooks | 1 |

Most participants were aware of key organ donation laws: 73 per cent knew organ trade was illegal, 69 per cent recognized the family’s final decision, and 53 per cent were aware of the existence of an organ donation law. However, awareness of organ donor cards was low, with only 19 per cent familiar with the concept and 34 per cent believing it was possible to change one’s mind after registering as a donor. The mean score for questions on organ donation laws was 2.5 out of 5. The results of awareness have been summarised in table II.

| Sl. no | Question | Correct response | Participants with correct response (Score=1) | Participants with incorrect response (Score=0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Heard of term ‘organ donation’ | - | 95 | 5 |

| 2. | Can organs be donated to save lives | - | 98 | 2 |

| 3. | When can organs be donated (while alive/after death) | Both | 52 | 48 |

| 4. | Any age limit to receive an organ | No | 60 | 40 |

| 5. | Any age limit to donate an organ | No | 60 | 40 |

| 6. | Awareness on brain death | - | 60 | 40 |

| 7. | What organs can be donated | -* | 49 | 51 |

| 8. | Need for organs greater than availability | Yes | 64 | 36 |

| 9. | Awareness of the organ donor card | - | 19 | 81 |

| 10. | Possibility of change after indicating to be a donor | Yes | 34 | 66 |

| 11. | Final decision of deceased organ donation depends on | Family members | 69 | 31 |

| 12. | Is it Legal to sell/buy organs | No | 73 | 27 |

| 13. | Is there a law to regulate organ donation | Yes (THOTA) | 53 | 47 |

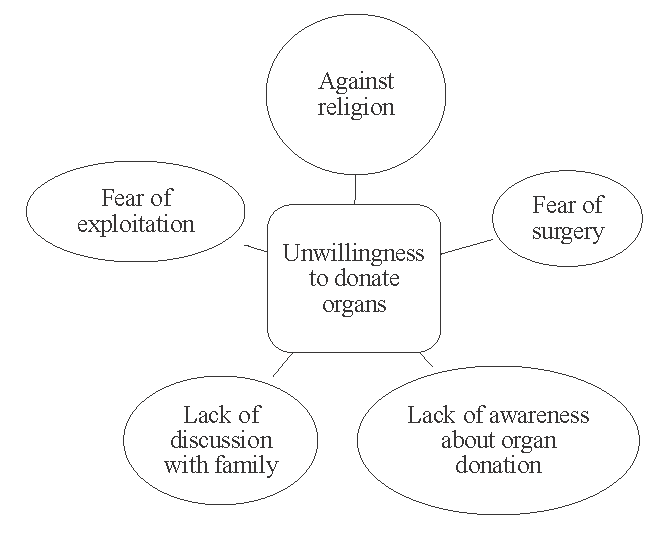

The mean perception score on organ donation was 67±9.41 (out of 86). For 16 of the 17 five point Likert scale questions, the median score was above 3.5 (Table III). About 95 per cent of participants supported organ donation. In terms of willingness, 51 per cent were willing to donate, 35 per cent were unsure, and 14 per cent were unwilling. The reasons for unwillingness were thematically analysed and presented in figure.

| Sl. no | Question | Strongly agree/agree | Neutral | Strongly disagree/disagree | Median perception score (out of 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | How do you feel about the donation of organs? | 95 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 2. | Willingness to donate your organs after death?* | 66 | 22 | 12 | 4 |

| 3. | Likelihood of donation to a family member?* | 83 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| 4. | Likelihood of donation to a friend?* | 53 | 25 | 22 | 4 |

| 5. | Likelihood to an unknown person?* | 23 | 19 | 58 | 2 |

| 6. | If you didn’t know your family member’s wishes, likelihood to donate organs upon their death?* | 54 | 19 | 27 | 4 |

| 7. | If you knew your family member wanted to donate organs, likelihood to donate organs upon their death? | 91 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| 8. | Organ donation should be promoted | 91 | 6 | 3 | 5 |

| 9. | It is important for a person’s body to have all of its parts when buried/cremated | 16 | 17 | 67 | 4 |

| 10. | It is possible to have a regular funeral service following organ donation | 88 | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| 11. | Organ donation is against your religion. | 11 | 6 | 83 | 5 |

| 12. | Every year, thousands of people die due to a lack of donated organs | 75 | 17 | 8 | 5 |

| 13. | Annually, the need for organs is less than its availability. | 32 | 13 | 55 | 4 |

| 14. | A poor person and rich person has equal chance of getting an organ transplant. | 61 | 1 | 38 | 4.5 |

| 15. | If you indicate you intend to be a donor, doctors will be less likely to try to save your life. | 13 | 13 | 74 | 4.5 |

| 16. | Doctors and hospitals will use organs as they are intended to be used. | 60 | 29 | 11 | 4 |

| 17. | People who donate a family member’s organs after death pay extra medical bills. | 9 | 25 | 66 | 4 |

- Reasons behind unwillingness to donate organs.

The likelihood of organ donation was dependent on the relationship between individuals. The median score decreased from a score of 5 for a family member to four for a friend and to 2 for an unknown person. A large majority of participants were more likely to donate the organs of their family members if they knew their family’s wishes (91%) compared to those who did not know (54%).

A significant majority (74%) believed that choosing to be an organ donor would not affect a doctors’ efforts to save their lives. A lesser proportion (60%) believed that there will be no misuse of donated organs. Most participants (61%) believed that both the rich and the poor have an equal chance for organ donation. The response to the Likert scale questions have been summarised in table III.

To understand the factors behind organ donation awareness, the various sociodemographic factors were subjected to bivariate analysis using the independent sample t-test or one-way ANOVA (Table IV). The variables of gender (P= 0.037), education (P< 0.001), per capita income (P= 0.014) and locality (P= 0.04) were significant with respect to the awareness score.

| Variable | Categories | n=100 | Mean knowledge score ± SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 45 | 8.47±2.57 | 0.037* |

| Female | 55 | 7.36±2.60 | ||

| Age (yr) | <30 | 36 | 8.39±2.48 | 0.123 |

| 30-45 | 46 | 7.85±2.29 | ||

| >45 | 18 | 6.83±3.50 | ||

| Religion ^ | Hindu | 62 | 7.46±2.63 | 0.166 |

| Christian | 21 | 8.33±2.90 | ||

| Muslim | 16 | 8.69±2.18 | ||

| Education | Grade 12 or below | 51 | 6.88±2.67 | <0.001** |

| Undergraduate/Postgraduate degree | 49 | 8.80±2.20 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 32 | 8.59±2.50 | 0.056 |

| Married | 68 | 7.51±2.65 | ||

| Occupation | Gainfully employed | 60 | 7.77±2.73 | 0.670 |

| Not gainfully employed | 40 | 8.00±2.52 | ||

| Works in healthcare profession | Yes | 13 | 7.77±2.68 | 0.895 |

| No | 87 | 7.87±2.64 | ||

| Per Capita Income | 0-5000 | 45 | 7.00±2.76 | 0.014* |

| 5001-10000 | 27 | 8.15±2.52 | ||

| 10001-15000 | 12 | 9.25±1.91 | ||

| 15001 and greater | 16 | 8.75±2.24 | ||

| Locality | Urban | 62 | 8.45±2.53 | 0.040* |

| Rural | 38 | 6.89±2.54 |

P*<0.05, **<0.001. ^While analysing religion, the category of ‘no religion’ with just one response was excluded. SD, standard deviation

To understand the true predictors of awareness levels, the variables with a P value less than 0.05 were selected for multiple linear regression. The regression [F(4,95)=6.25; R2=0.208] was run to predict the awareness levels from gender, education, per capita income and locality. Only the education level was a statistically significant predictor (P= 0.036) of organ donation awareness levels.

Discussion

The results of the study show that most participants had adequate awareness about organ donation and had a positive perception towards it. A previous study done on the general public in 2016 in an urban area in India15 estimated an awareness of 52.8 per cent. The increased rate of awareness in this study could be due to increased publicity in mass media. Participants had conveyed that media (like movies, news reports) in the last decade started spreading awareness on the topic. However, the awareness levels still remain less as compared to studies done globally in countries like the USA and Saudi Arabia which showed an awareness level of around 86 per cent and 90 per cent, respectively18,19. In line with previous studies done both in India and globally20–22, mass media was attributed as the main source of awareness. Additionally, only 23 per cent attributed their knowledge to healthcare personnel. This is consistent with previous studies done in India15,23, and highlights the need to increase medical sources of awareness. With respect to the laws regarding organ donation, there is increased awareness as compared to previous studies done on medical students in India20,24. However, awareness of the organ donor card was low, with only 20 per cent being aware. Hence, media campaigns should focus on promoting donor cards.

In terms of perceptions, there was a positive perception in general. Similar to a previous study on the general public in India15, the majority (95 per cent) supported organ donation. Participants were also more likely to donate the organs of their family members if they knew their family’s wishes. This is consistent with a systematic review done by Vincent et al9, which revealed that even though a number of individuals were willing to donate their organs, a large proportion never expressed their wish to donate their organs to their family due to the discomfort associated with the conversation, hence this remained a barrier to donate. Additionally, family members may hesitate to make a decision on donating the organs of a deceased loved one due to emotional stress. Hence public campaigns should encourage people to discuss their donation-related wishes with their family and friends.

The likelihood of donating organs was also dependent on the relation between the donor and recipient. This is in line with the findings of studies done in both Pakistan and China on perceptions regarding organ donation which show that family members and relatives are the preferred potential recipients compared to other groups for living transplants25,26.

In this study, about half of the participants were willing to donate their organs, which is slightly lower than a previous study on the general public in India15. Reasons for unwillingness included fear of exploitation, religious beliefs, lack of awareness, and lack of discussion; these were consistent with a systematic review done in 2022 on organ donation barriers9. These issues need to be addressed by both governmental and non-governmental organizations. Moreover, although 95 per cent of participants supported organ donation, only 51 per cent were willing to donate. Further qualitative studies can be done on groups such as family members who declined organ donation to provide insights into this gap and find strategies to tackle it. Additionally, interventional studies on ways to motivate individuals to donate organs would be beneficial.

Only about half of the participants believed there would be no misuse of organs and that organ allocation is not influenced by financial status. In reality, organ donation is not based on wealth or social status. The fear of misuse remains a barrier to organ donation, which could be addressed through increased transparency in organ transplant allocation methods and by raising awareness about the regulatory bodies in place.

Our study showed that gender, education levels, per capita income and locality showed statistical significance with respect to knowledge levels. Gender differences could have been noted as women have lower literacy rates in India as compared to men27. However, multiple linear regression analysis showed that only education was a factor associated with awareness levels. This is in line with a study done in Pakistan, however it additionally included per capita income as a predictor of awareness levels25.

The study’s implications are relevant for both hospital administration and policymakers. Hospital administrations can play a key role in promoting organ donation awareness among the general public and address barriers such as mistrust in the system. At the policy level, adopting an ‘opt-out’ system, like those in Spain and Singapore, where individuals are automatically considered organ donors, could potentially improve donation rates compared to the current ‘opt-in’ system in India28,29.

The study had a robust methodology which included usage of a validated study tool, selection of attendants through simple random sampling and administration of the interview schedule in the first language of the participants. Attendants were interviewed from both the private and general ward to ensure a representation of various socio-economic strata. However, the limitations include that the sample size was quite small. Moreover, the sample size was estimated for the primary objective and therefore it may have been underpowered for subgroup analysis done as the secondary objective.

Financial support & sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation. Available from: https://www.irodat.org/?p=publications, accessed on October 16, 2022.

- On the way to self-sufficiency: Improving deceased organ donation in India. Transplantation. 2021;105:1625-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatal road traffic accidents and their relationship with head injuries: An epidemiological survey of five years. Indian J Neurotrauma. 2008;5:63-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Road Accidents in India Report. Available from: https://morth.nic.in/road-accident-in-india, accessed on January25, 2022.

- COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide organ transplantation: A population-based study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e709-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Global transplant data. Available from: http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-charts-and-tables/, accessed on October 16, 2022.

- Barriers and suggestions towards deceased organ donation in a government tertiary care teaching hospital: Qualitative study using socio-ecological model framework. Indian J Trans. 2019;13:194-201.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Deceased organ donation and transplantation in India: Promises and challenges. Neurol India. 2018;66:316-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers towards deceased organ donation among Indians living globally: An integrative systematic review using narrative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e056094.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation among doctors and students of a tertiary care hospital. Artif Organs. 2021;45:625-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enlightening young minds: A small step in the curriculum, a giant leap in organ donation-A survey of 996 respondents on organ donation and transplantation. Transplantation. 2021;105:459-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and practice of organ donation among police personnel in Tamil Nadu: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Trans. 2020;14:141.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Awareness about brain death and attitude towards organ donation in a rural area of Haryana, India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10:3084-88.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions and attitudes towards organ donation among people seeking healthcare in tertiary care centers of coastal South India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19:83-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the general population towards organ donation: An Indian perspective. Natl Med J India. 2016;29:257-61.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices, 2019: Report of Findings. Available from: https://www.organdonor.gov/sites/default/files/organ-donor/professional/grants-research/nsodap-organ-donation-survey-2019.pdf, accessed on January 25, 2022.

- Evaluation of oxidant-antioxidant balance and total antioxidant capacity of serum in children with urinary tract infection. Niger Med J. 2016;57:114-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Public knowledge and attitudes regarding organ and tissue donation: An analysis of the northwest Ohio community. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58:154-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public awareness survey about organ donation and transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:3469-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude, and perception on organ donation among undergraduate medical and nursing students at a tertiary care teaching hospital in the southern part of India: A cross-sectional study. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:161.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions and attitudes towards organ donation among people seeking healthcare in tertiary care centers of coastal South India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2013;19:83-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and ethical perception regarding organ donation among medical students. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A study on knowledge, attitude and practices about organ donation among college students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu-2012. Prog Health Sci. 2013;3:59.

- [Google Scholar]

- The perspective of our future doctors towards organ donation: A national representative study from India. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020;34:197-204.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes and practices survey on organ donation among a selected adult population of Pakistan. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10:5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and willingness toward living organ donation: A survey of three universities in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1303-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing global organ donation policies: Opt-in vs Opt-out. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1985-98.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: A panel study. BMC Med. 2014;12:131.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]