Translate this page into:

Asymptomatic bacteriuria & obstetric outcome following treatment in early versus late pregnancy in north Indian women

Reprint requests: Dr Vaishali Jain, A-126, Shree Nathji Vihar, 538 Sitapur Road, Lucknow 226 020, India e-mail: vairul@rediffmail.com

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy if left untreated, may lead to acute pyelonephritis, preterm labour, low birth weight foetus, etc. Adequate and early treatment reduces the incidence of these obstetric complications. The present study was done to determine presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) and obstetric outcome following treatment in early versus late pregnancy.

Methods:

A prospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital of north India. Pregnant women till 20 wk (n=371) and between 32 to 34 wk gestation (n=274) having no urinary complaints were included. Their mid stream urine sample was sent for culture and sensitivity. Women having > 105 colony forming units/ml of single organism were diagnosed positive for ASB and treated. They were followed till delivery for obstetric outcome. Relative risk with 95% confidence interval was used to describe association between ASB and outcome of interest.

Results:

ASB was found in 17 per cent pregnant women till 20 wk and in 16 per cent between 32 to 34 wk gestation. Increased incidence of preeclamptic toxaemia (PET) [RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.80-7.97], preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM)[RR 3.63, 45% CI 1.63-8.07], preterm labour (PTL) [RR 3.27, 95% CI 1.38-7.72], intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)[RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.80-79], low birth weight (LBW) [RR1.37, 95% CI 0.71-2.61] was seen in late detected women (32-34 wk) as compared to ASB negative women, whereas no significant difference was seen in early detected women (till 20 wk) as compared to ASB negative women.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Early detection and treatment of ASB during pregnancy prevents complications like PET, IUGR, PTL, PPROM and LBW. Therefore, screening and treatment of ASB may be incorporated as routine antenatal care for safe motherhood and healthy newborn.

Keywords

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

early detection

foetomaternal outcome

IUGR

late detection

low birth weight

Profound physiologic and anatomic changes in the urinary tract during pregnancy contribute to the increased risk for infection. Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is defined as a pure culture of at least 105 organisms/ml of urine in the absence of symptoms1. It is the most common bacterial infection requiring medical treatment in pregnancy. A prevalence of 2 -10 per cent has been reported23.

Maternal and foetal complications attributed to it are symptomatic urinary tract infection (UTI), pyelonephritis, preeclamptic toxaemia (PET), anaemia, low birth weight (LBW), intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), preterm labour (PTL), preterm premature rupture of membrane (PPROM) and post-partum endometritis45. Although first trimester screening and treatment for ASB during pregnancy is standard-of-care in developed countries and the role of specific antimicrobial therapy in pregnancy is well established6, information is not available from developing countries on the impact of antimicrobial therapy for ASB during pregnancy. There is considerable evidence, however, that bacteriuria is widespread in India and neighbouring countries7891011.

Thus, the present study was undertaken to know the burden of disease and to compare the obstetric outcome in women detected and treated for ASB in early pregnancy with those detected and treated late in pregnancy following late registration in north India.

Material & Methods

A prospective cohort study over a period of two years was done in outpatient antenatal clinic in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of a north Indian tertiary care teaching hospital. Asymptomatic pregnant women till 20 wk of gestation (Group A, n=371) and between 32-34 wk (Group B, n=274) were enrolled for this study after obtaining informed written consent. Ethical clearance for study protocol was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Pregnant women having history of intake of antibiotic, vaginal bleeding, having symptomatic UTI (increased frequency of urination, burning micturition), fever with chills, suprapubic pain, multiple pregnancy, history of preterm delivery, PPROM, IUGR, pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) in previous pregnancy, recurrent UTI and diabetes were excluded from the study. Considering the prevalence rate of ASB from studies in Indian subcontinent7891011 at variable gestational ages to be 12 per cent among pregnant women, sample size was estimated to be 163 with 5 per cent absolute error at 95 per cent confidence level. In view of considerably higher rate of lost to follow up in our hospital more women were enrolled for the study.

Study protocol & treatment: A midstream specimen of urine was obtained in the clinic from the women and was sent for culture and sensitivity within two hours of collection. Culture of microorganisms in urine was done on CLED (cysteine lactose electrolyte deficient) medium/MacConkey agar and blood agar using standard loop ((Semiquantative method)12. The plates were read after 24 h of aerobic incubation at 37° C. They were incubated for another 24 h before a negative report was issued. A sample with single organism obtained in counts >105 colony forming units (cfu/ml) was taken as positive. Sensitivity testing was done using drugs safe in pregnancy namely amoxycillin, ampicilin, cephalexin, cefuroxime, cefotaxim, amikacin, gentamicin and nitrofurantoin. Women from both the groups diagnosed of having ASB on the basis of urine culture report were treated as per the antibiotic sensitivity for 7 days. Clearance of bacteriuria was documented after the therapy was completed. The follow up culture was done one week after completion of therapy. All women in whom infection persisted were given a repeat course of antibiotics as per sensitivity report and clearance of infection was documented.

Outcome variables: All women were followed till delivery. A special note was made for the development or presence of maternal complications like symptomatic UTI (dysuria, frequency of micturition, fever), pyelonephritis (high grade fever, chills, costovertebral angle tenderness), anaemia (Hb<11 g/dl in 1st and 3rd trimester, <10.5 g/dl in 2nd trimester), preeclamptic toxaemia (blood pressure >140/90 mmHg, proteinuria >300 mg/24 h or >1+ dipstick), preterm labour (contractions four in 20 min or eight in 60 min, cervical dilatation >1 cm, cervical effacement >80 per cent before 37 wk of gestation), preterm premature rupture of membrane (on per speculum clear fluid coming from cervix before 37 wk of gestation, before onset of labour), intrauterine growth restriction (foetal weight below the 10th percentile for its gestational age) and puerperal pyrexia (oral temperature >38.0° C between day 2 to 10 postpartum on atleast two occasions. Foetal outcomes like low birth weight (birth weight <2500 g), neonatal septicaemia (hypothermia or fever, poor cry, refusal to suck, hypotonia, absent neonatal reflexes, bradycardia/ tachycardia, respiratory distress, positive blood culture) were also noted. Gestational age at delivery and mode of delivery were recorded for all patients. On follow up 41 of 371 (11.1%) women in group A and 22 of 274 (8%) in group B were lost. Of these, five women in group A and two in group B were ASB positive. The remaining were analysed and labelled as early detected (ASB positive in group A, n=58), late detected (ASB positive in group B, n=44) and ASB negative (n=480).

Statistical analysis: Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0 was used to analyze the data. Baseline characteristics have been reported as mean ± SD. Student “t” test was used to compare the data between two groups. Proportional differences were compared using Fisher's exact test. For univariate analysis, relative risk was computed to seek an association of independent variables with the corresponding outcome. Multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression.

Results

Sixty three women in group A (17%) and 46 in group B (16%) were found to be culture positive. Thus the occurrence of ASB was 16.9 per cent. The baseline characteristics of the ASB positive and ASB negative women in both the groups were comparable. In early detected group mean age of the women was 25.40 ± 3.93 yr, 42.8 per cent (27/63) of them were nullipara and 74.6 per cent (47/63) belonged to urban area. In late detected group mean age of the women was 25.41 ± 3.59 yr, 44.6 per cent (21/46) were nullipara and 86.9 per cent (40/46) belonged to urban area. Escherichia coli detected in 41 (37.6%) women was the most frequently isolated organism followed by Enterococcus spp. in 23 (21.1%) of the cases. Other bacteria isolated were Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., coagulase negative Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter. Most commonly prescribed antibiotics were cephalaxin in 34.8 per cent (38/109) and Nitrofurantoin in 28.4 per cent (31/109) ASB positive women. In some women cefuroxime, amoxicillin, amikacin were also prescribed; 1.7 per cent (1/58) women in early detected group and 2.3 per cent (1/44) women in late detected group required a repeat antibiotic therapy. Overall, one woman in early detected group developed acute pyelonephritis and one in late detected group developed symptomatic UTI.

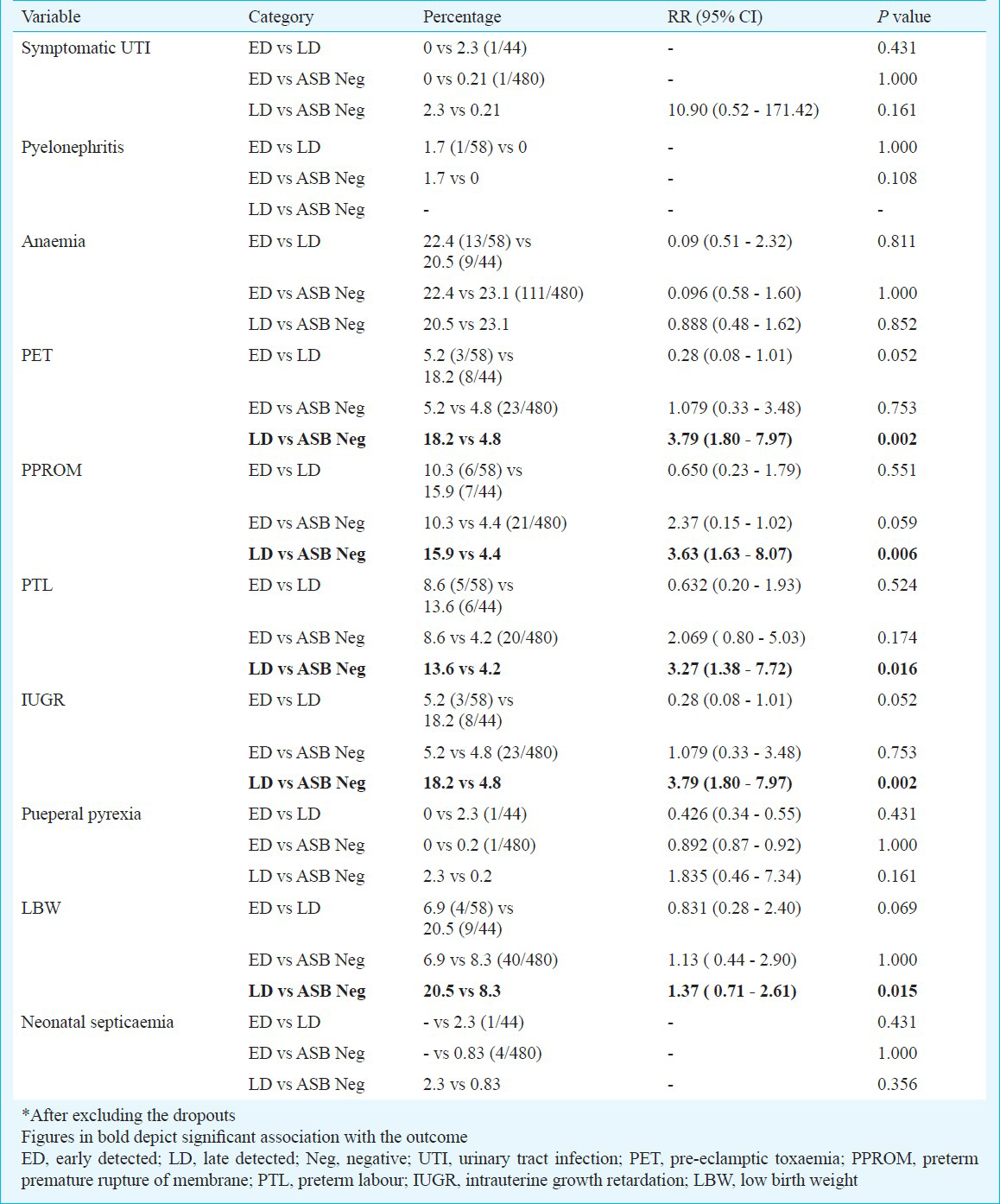

Table 1 shows the obstetric outcome in early detected, late detected and ASB negative women. There was no significant difference in the development of symptomatic UTI, acute pyelonephritis, anaemia, puerperal pyrexia and neonatal septicaemia in the three groups. Increased incidence of PET (RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.8 - 7.97, P=0.002), PPROM (RR 3.63, 95% CI 1.63 - 8.07, P=0.006), PTL (RR 3.27, 95% CI 1.38-7.72, P=0.016), IUGR (RR 3.79, 95% CI 1.80-7.97, P=0.002) and LBW (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.71-2.61, P=0.015) was seen in late detected women as compared to ASB negative women.

From these crude associations, PET, PPROM, PTL, IUGR were selected for multivariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression model was applied to determine their dependency on positive urine culture test besides other factors (Table II). PET, PTL, PPROM, IUGR were found as a dependent function of positive culture sensitivity and anaemia.

Discussion

The risk of developing symptomatic UTI and acute pyelonephritis in pregnant women with ASB is well established. Hill et al13 reported an incidence of 1.4 per cent of acute pyelonephritis in pregnancy. This is less than the reported rate of 3-4 per cent in the early 1970s before screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria became a routine. Smaill et al in a systematic review showed the overall incidence of pyelonephritis in the untreated ASB group to be 21 per cent with a range of 2.5 to 36 per cent14. Treatment of ASB led to approximately a 75 per cent reduction in the incidence of pyelonephritis14. Successful treatment also reduces the rate of subsequent symptomatic UTI by 80-90 per cent15. In our study only one woman in late detected group developed symptomatic UTI and one woman in early detected group developed pyelonephritis even though urine culture was sterile after second course of antibiotics. Also, in most cases culture sensitivity to cephalexin and nitrofurantoin was found. Different studies have shown nitrofurantoin/fosfomycin as drug of choice during pregnancy1617. Choice of antibiotics for the treatment should be guided by antimicrobial susceptibility whenever possible16.

The relationship of ASB with other maternal and foetal complications remains an area of continued debate. The incidence of anaemia was found to be high in all the groups despite treatment. The strength of association between ASB and anaemia could not be established due to the multipronged aetiopathogenesis of anaemia during pregnancy18.

ASB is known to be associated with IUGR, PTL, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and LBW infants1. Sheiner et al19 conducted a retrospective population based study by multivariate analysis with backward elimination. They showed that ASB was independently associated with PTL (adjusted OR =1.6%; 95% CI 1.5-1.7; P<0.001), hypertensive disorders and IUGR. In the present study late detected women showed 3.79 times increased chances of developing PET and IUGR as compared to ASB negative women whereas women detected and treated early in pregnancy did not show increased chances of these complications. This finding emphasizes the importance of early detection and treatment of ASB. It was observed that IUGR and PET case groups were independent of each other.

Even after treatment late detected women showed 3.27 times increased chances of developing preterm labour as well as 3.63 times increased chances of PPROM as compared to ASB negative women. At the same time no difference could be found between early detected women as compared to ASB negative women. Risk of developing LBW baby in late detected group was found to be increased in comparison to ASB negative group (RR 1.37; 95% CI 0.71-2.61). Smaill et al14 showed reduction in the incidence of pyelonephritis (RR 0.23; 95% CI 0.13-0.41) and low birth weight (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.49-0.89), after antibiotic treatment in women with ASB. However risk of preterm delivery was not reduced (RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.10-1.36) even after treatment. They concluded that a reduction in low birthweight was consistent with current theories about the role of infection in adverse pregnancy outcomes, but this association should be interpreted with caution given the poor quality of the included studies14. Adam et al20 suggested that screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria during antenatal care will be one of the most cost-effective interventions at the primary care level for mothers and newborns in developing countries to achieve the millennium development goals for health. Our findings also indicate the same. In early detected women the chances of developing maternal and foetal complications were significantly reduced after treatment. However, late detected women have shown increased chances of developing PET, PPROM, PTL, IUGR, LBW as compared to ASB negative group despite adequate treatment. However a limitation of our study is that we have not investigated for all other factors reported to influence the occurrence of these complications during pregnancy. A larger multicentric community based study is required for to find these associations.

In conclusion, the present study showed high occurrence of ASB in pregnant women. It also demonstrated that if disease was detected late in pregnancy it might lead to various maternal and neonatal complications like PET, PTL, PPROM, IUGR and LBW despite treatment of infection. All the sequelae of ASB during pregnancy could be reduced by antimicrobial treatment early in pregnancy. Hence, screening and treatment of ASB need to be incorporated as routine antenatal care for an integrated approach to safe motherhood and newborn health.

Acknowledgment

The first author (VJ) acknowledges CSIR (Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, Human Resource Development Group), New Delhi, for senior research associateship and Department of Microbiology for laboratory work.

References

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria and symptomatic urinary tract infections in pregnancy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008;38:50-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The uriscreen test to detect significant asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:50-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which antibiotics are appropriate for treating bacteriuria in pregnancy? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46(S1):29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Should asymptomatic bacteriuria be screened in pregnancy? Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2002;29:281-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatments for symptomatic urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD002256.

- [Google Scholar]

- High prevalence of bacteriuria in pregnancy and its screening methods in north India. J Indian Med Assoc. 2005;103:259-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria in antenatal women. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:105-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women. Pak J Med Sci. 2006;22:162-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria and its consequences in pregnancy in a rural community of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2007;33:60-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, detection and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in a Turkish obstetric population. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:627-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory strategy in the diagnosis of infective syndrome. In: Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marmiom BP, Simmons A, eds. Practical medical microbiology. Singapore: Churchill Livingstone Publishers, Longman; 2003. p. :53-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD000490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:95-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria and antibacterial susceptibility patterns in an obstetric population. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2011;721872:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalance and complications of asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Prof Med J. 2006;13:108-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. J Maternfetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:423-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Achieving the millennium development goals for health- cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ. 2005;331:1107-12.

- [Google Scholar]