Translate this page into:

Association of Chlamydia trachomatis infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) & cervical intraepithelial neoplasia - A pilot study

Reprint requests: Dr Neerja Bhatla, Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences Ansari Nagar, New Delhi 110 029, India e-mail: neerja.bhatla07@gmail.com, nbhatla@aiims.ac.in

-

Received: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background & objectives:

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the necessary cause of cervical cancer and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) is considered a potential cofactor in the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). The objective of this pilot study was to determine the association of CT infection with HPV, other risk factors for cervical cancer, and CIN in symptomatic women.

Methods:

A total of 600 consecutively selected women aged 30-74 yr with persistent vaginal discharge, intermenstrual/postcoital bleeding or unhealthy cervix underwent conventional Pap smear, Hybrid Capture 2® (HC2) testing for HPV and CT DNA and colposcopy, with directed biopsy of all lesions.

Results:

HPV DNA was positive in 108 (18.0%) women, CT DNA in 29 (4.8%) women. HPV/CT co-infection was observed in only four (0.7%) women. Of the 127 (21.2%) women with Pap >ASCUS, 60 (47.2%) were HPV positive and four (3.1%) were CT positive. Of the 41 women with CIN1 lesions, 11 (26.8%) were HPV positive, while two were CT positive. Of the 46 women with CIN2+ on histopathology, 41 (89.1%) were HPV positive, two (4.3%) were CT positive and one was positive for both. The risk of CIN2+ disease was significantly increased (P<0.05) by the following factors: age <18 yr at first coitus, HPV infection and a positive Pap smear. Older age (>35 yr), higher parity, use of oral contraceptives or smoking did not show any significant association with HPV or abnormal histopathology. Parity >5 was the only risk factor positivity associated with CT infection (P<0.05).

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our findings showed that CT infection was not significantly associated with CIN, and most of its risk factors, including HPV infection, in symptomatic women. Longitudinal studies with carefully selected study sample would be able to answer these questions.

Keywords

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Chlamydia

CIN

HPV

human papillomavirus

Cervical cancer is the most common malignancy among women in India1. Infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (hrHPV) has been shown to be a necessary cause of cervical cancer2. However, it is not sufficient and only a small number of exposed women will develop persistent infection or progress to cervical neoplasia. Proposed cofactors include co-infection with other microorganisms (Herpes simplex virus, Chlamydia trachomatis), cigarette smoking, oral contraceptives, early sexual debut, multiparity, low socio-economic status, immunosuppression, chronic inflammation, nutritional deficiencies, HLA status, gene polymorphisms in antigen-processing proteins and other host genetic/immunologic responses34.

C. trachomatis (CT) is a common sexually transmitted infection. Its role in cervical carcinogenesis as a co-factor for HPV has been extensively investigated with mixed results. CT infection has been reported to increase the risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix56. This association has been demonstrated using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results6 as well as antibody titres7 as a measure of CT infection. A higher prevalence of CT infection in HPV positive samples when compared to HPV negative samples has been reported in several studies89. However, others have reported no correlation or negative correlation in this context1011.

CT infection is easily treatable, and therefore, may be an important therapeutic target for prevention of cervical neoplasia. However, the vast majority of the data about Chlamydia in cervical carcinogenesis is from developed countries. CT has been reported to be the most common microorganism associated with cervical dysplasia12, and also associated with an 8-fold increase in the risk of unhealthy cervix13. However, Singh et al14 did not find chlamydial infection associated with an increased risk of progression of inflammatory smear to squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL).

The present study was undertaken to investigate the association of CT infection with hrHPV infection, and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in symptomatic Indian women.

Material & Methods

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out in the outpatient clinics of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India, from October 2005 to October 2007. Sexually active women aged 30-74 yr presenting consecutively to the OPD with symptoms of persistent vaginal discharge for over 6 months, intermenstrual/postcoital bleeding or detected to have an unhealthy cervix on examination were invited to participate in this study. The Institute Ethics Committee approved the study protocol. Informed written consent was taken from the women, informing them about the background of the study, risks and benefits and voluntary nature of participation.

Information was collected from all women pertaining to their age, parity, socio-economic status15, and smoking and contraception history. Subjects were evaluated for clinical features of other STIs on history and examination. An HIV test (ELISA) was conducted on all subjects. Other causes or features of immunosuppression were not evaluated.

Two cervical samples were collected from each woman, one for conventional Pap smear obtained using an Ayre's spatula and a cytobrush and another in specimen transport medium (STM) aliquoted for hrHPV and CT DNA testing and stored at -80°C.

Pap smears were reported using the Bethesda system terminology16 and results were available within two weeks of the Pap smear being taken. HPV DNA and CT DNA were both assayed using the Hybrid Capture 2™ (HC2) assay (Qiagen Gaithersburg Inc., MD, USA), performed using the microwell format and probes for high oncogenic risk HPV types (i.e. types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59 68) and C. trachomatis. HC2 is a signal amplification solution hybridization assay, which utilizes unlabelled RNA probes and a chemiluminiscent reporter system to provide sensitive and specific detection in less than 5 h. A single amplification method couples hybridization to an antibody capture microplate system. The assay is performed in two steps. The initial test indicates the presence of the microbe in the sample. The second test identifies the specific organism. Assay results were reported as relative light units (RLU) of HPV DNA in the sample. A sample was considered to be positive if the ratio of the sample RLU to the positive control RLU is >1.0.

All women underwent colposcopy and guided biopsies. Colposcopic lesions were graded using the Reid Colposcopic Index17. Endocervical curettage was performed if no lesions were visible. Biopsy was carried out for all lesions on colposcopy, i.e., Reid score of >0. Final reference diagnosis was based on histopathology, which was classified into five classes namely, normal or inflammatory, CIN 1, CIN 2, CIN 3 and invasive cancer.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS 16.0 statistics software, USA. Cytology was reported according to the Bethesda System16. Cases were stratified as normal, low and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive cervical cancer based on results of colposcopy and directed biopsy. Data are reported as number (percentage) and median (range). Association of outcome and exposure was tested with Fischer exact test and exposure to more than two categories with the non parametric trend χ2- test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Six hundred and eighteen eligible women were enrolled in the study. Complete information for analysis was available for 600 women. The median age was 36.0 yr (range 30-74 yr), with 374 (62.3%) women in the age group of 30 to 39 yr. The median age at marriage was 17 yr (range 17-33 yr), at first coitus 18 yr (range 11-34 yr) and at first pregnancy 20 yr (range 13-34 yr). Sixty women had parity >5. Oral contraceptive pill (OCP) use was reported by 47 (10.3%) women. No woman was positive for HIV.

Risk factors for cervical neoplasia: Of the 600 women, 379 (63.2%) were over 35 yr of age; 355 (59.2%) were younger than 18 at the time of first coitus; 341 (56.8%) were younger than 20 yr at the time of first child-birth and 218 (36.3%) had a parity of 4 or more. About half (n=302, 50.3%) belonged to the lower socio-economic strata, 192 (32%) women were smokers, 260 (57%) women reported condom use, with only 109 (18.2% of total) reporting regular use.

High risk HPV infection was detected in 108/600 (18.0%) subjects. hrHPV prevalence was highest (69%) in the age-group 25 to 39 yr of age, followed by 28.7 per cent (31/108) in the age group 40-49 yr. Twenty nine (4.8%) women tested positive for CT. CT prevalence was highest in the age group 25 to 39 yr (20/29 CT+ subjects, 68.9%), followed by 40 to 49 yr (8/29, 27.6%). CT-HPV co-infection was found in only four women (0.7%).

Cytology, CT DNA and HPV DNA: Abnormal Pap smear (>ASCUS) was found in 127 (21.2%) women. Ten (1.6%) smears were inadequate. Among the 463 cytology negative subjects (excluding the inadequate smears), a majority were negative for both CT and HPV infection (389, 84.0%). Only 47 (10.2%) were hrHPV DNA positive and 24 (5.2%) were CT DNA positive. Three of these were those with CT-HPV co-infection. The majority of the benign Pap smears positive for HPV or CT were inflammatory smears (34/47 and 20/24, respectively).

Among abnormal Pap cases (>ASCUS), 60 (47.2%) were hrHPV DNA positive and 5(3.9%) were CT DNA positive. Of the 60 subjects with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), 15 (25%) were hrHPV infected, while only three (5%) were CT-infected. Of the 48 subjects with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), 40 (83.3%) were hrHPV infected, while only one had CT infection, and she was also co-infected with HPV.

Cervical neoplasia and CT and HPV DNA positivity: Of the 361 (60.2%) women with suspicious findings on colposcopy, subsequent biopsy detected CIN in 87 women: CIN1 in 41, CIN 2 in 20, CIN3 in 19 and invasive cancer in seven.

Among the 87 women with CIN, 32 were negative for both hrHPV and CT DNA. Among the 41 CIN1 cases, a majority (28, 68.3%) were not infected by HPV or CT. Among 46 patients with CIN2 or worse (CIN2+) lesions on histopathology, 41 (89.1%) were hrHPV positive, two (4.3%) were CT positive. One of these patients was infected with both organisms. All seven cases of invasive cancer were positive for hrHPV DNA. The odds ratio (OR) of CIN2+ for hrHPV infection was 50.5 (95% CI=18.9-134.8, P<0.0001).

Concurrent CT and HPV infection: Of the four women with both CT and hrHPV infection, one had HSIL on Pap, while three had inflammatory smears. However, on biopsy, the case with HSIL had only chronic cervicitis, while one of the three patients with benign smears had CIN2. Overall, subjects with both hrHPV and CT positivity showed no significant association with abnormal Pap smears (>ASCUS) compared with hrHPV infection alone [P=0.210, OR 0.3 (0.0-2.5)], or histopathology CIN2+ [P=0.341, OR 0.342 (0.034-3.424)].

Association of risk factors with hrHPV and CT infection and CIN

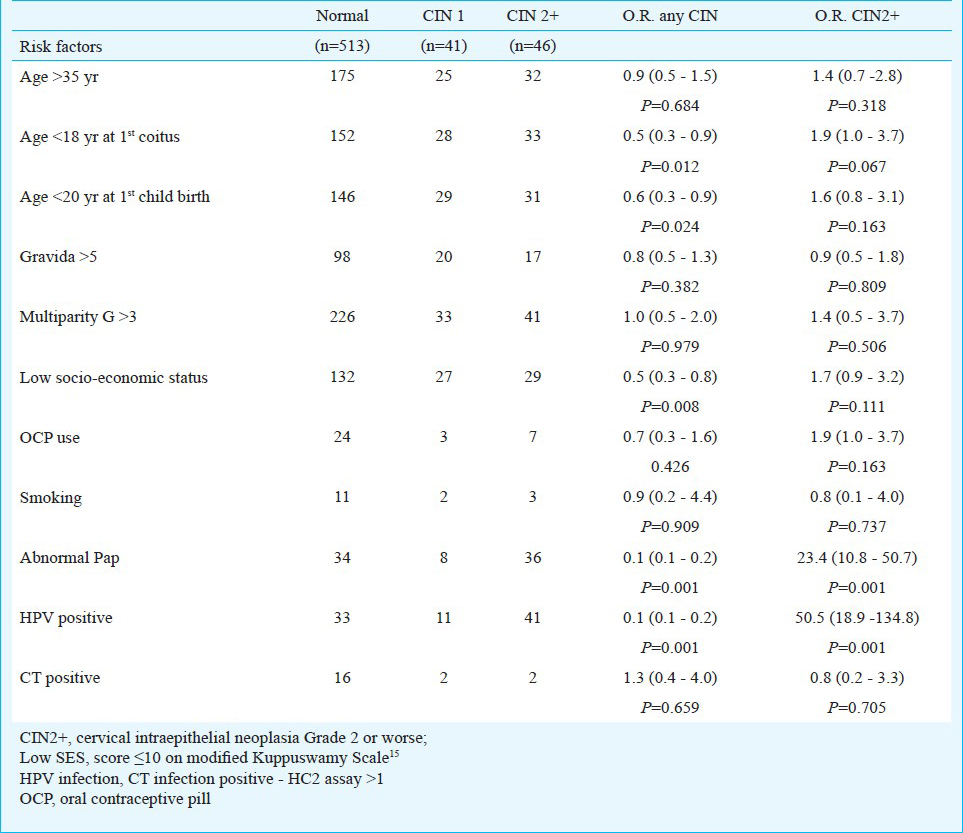

Eight risk factors were evaluated for association with risk of CT infection, HPV infection and CIN, namely, older age (≥35 yr) low socioeconomic status (score of ≤10 on the modified Kuppuswamy Scale17), gravida >5, smoking, OCP use, age ≤18 yr at first coitus, age ≤20 yr at first pregnancy, and Pap report ≥ASCUS.

Among the risk factors evaluated, gravida >5 was the only risk factor that demonstrated a significant association with CT infection (P=0.049, data not shown). Age ≤18 yr at first coitus (P=0.003), ≤20 yr at first pregnancy (P=0.003), low socioeconomic status [score of ≤10 on the modified Kuppuswamy Scale15 (P=0.004) and Pap ≥ASCUS (P=0.000) increased the risk of high-risk HPV infection. Older age (≥35 yr), gravida >5, OCP use or smoking did not show any significant correlation with hrHPV infection (data not shown).

Age ≤18 yr at first coitus (P=0.067), hrHPV infection (P=0.001) and abnormal Pap smear (P=0.001) increased the risk of biopsy-proven CIN2+ disease (Table).

Discussion

HPV DNA has been detected in 99.7 per cent of cervical cancer from all geographic areas2 and in high numbers - 98.1 and 94.6 per cent in reports from India1819. Genital Chlamydia infection is a proposed co-factor. Its action in cervical dysplasia and neoplasia has been attributed to epithelial damage allowing easier HPV virion entry, inflammatory state leading to high levels of reactive oxygen species, initiation of cell division and metaplasia and reduction of host cell-mediated immunity. In their multicentric study, Smith et al6 reported an increased risk of invasive cervical cancer in CT seropositive women after adjustment for age, study-center, oral contraceptive use, history of Pap smears, number of full-term pregnancies and HSV2 seropositivity. Paba & colleagues20 reported altered levels of mediators of cell cycle and immune response in cases of synchronous co-infection. CT infection leads to persistence of HPV infection2122. Concurrent infection with C. trachomatis or another HPV type at the initial visit was found to be associated with persistence of high-risk HPV infections21.

While conventional culture is relatively sensitive and highly specific for CT detection, it is labour intensive and not suitable for screening large numbers. Further, widely varying techniques are followed in different institutions for specimen collection, storage, transport to tissue culture conditions and culture medium. Other methods for diagnosis developed over the past few years, include direct immunofluorescence, enzyme immunoassays, DNA probe techniques and molecular diagnostics, e.g. PCR, ligase chain reaction and transcription-mediated amplification. We used the Digene HC2 assay for CT detection, which has been reported to have a higher sensitivity and specificity than culture and PCR. The same specimen can be used to detect HPV, CT and gonococci, thus simplifying screening23. Gridner et al24 reported sensitivity and specificity of 95.4 and 99 per cent, respectively for HC2, and 90.8 and 99.6 per cent, respectively for PCR. The sensitivity of CT culture in the same study was 81.5 per cent, which was significantly lower than both HC2 and PCR24. Similar test performance was reported from other studies2325.

In establishing CT infection as a cofactor of HPV in the development of cervical neoplasia we hoped to achieve a possible simple solution to one of the risk factors. The women in our study were symptomatic women expected to have a higher frequency of CIN. The CT positivity was 4.8 per cent, lower than reported in contemporary studies from other regions in India - 7.3 per cent from Goa from an STD clinic and 7.0 per cent from a Gynaecology OPD in Orissa.2627. This may be because our sample did not include women younger than 30 yr of age, an age group that has a higher prevalence of Chlamydia infection, possibly because of greater sexual activity. However, this trend may vary with women's education and prevalent socio-cultural practices, especially relevant in the Indian context. The CT positivity rates in the present study were similar to those reported from high-risk populations in other countries: 4.3 per cent (adjusted for age) in patients at a cervical cancer screening clinic in Korea28 and 6-20 per cent in STD clinics in the US29. Highest positivity was observed in youngest age group of 30-39 yr. Singh et al30 in their study on symptomatic women reported CT prevalence rate 28 per cent in women aged 18-25 yr using plasmid PCR, but only 3.2 per cent in those aged 35-45 yr.

The rate of hrHPV and CT co-infection in our symptomatic study sample was correspondingly low, only 0.7 per cent. Individually CT infection rate in hrHPV positive subjects was only 3.7 per cent and 5.1 per cent in hrHPV negative subjects, co-infection has been reported in 1-5 per cent911. CT positivity has been reported in 9-36 per cent of hrHPV positive samples911.

In the present study, there was no association of CT infection with cytopathology ≥ASCUS or histopathology ≥CIN2+. A majority of the CT infected women had benign cytology. CT positivity in CIN was 5.1 per cent, while none of the women with cervical cancer were CT positive. Kwaśniewska et al31 reported a prevalence of CT of 26 per cent in squamous cell cervical carcinoma, significantly higher than the 8 per cent reported in controls. In their study on Indian women with STIs, Gopalkrishna et al8 reported CT in 12 per cent of the precancerous and 22 per cent of cancerous lesions (using Chlamydia plasmid based PCR assay), and HPV in 52 and 72 per cent, respectively. A population-based prospective study of 26 yr found the relative risk of cervical cancer associated with past CT infection, adjusted for concomitant HPV positivity was 17.1 (95% CI 2.6-α)32. All women positive for CT at baseline (8%) subsequently developed invasive cancer but none of the cancer biopsy specimens showed CT positivity32. The lack of association between CT and HPV and with CIN seen in our study has been reported earlier also1131.

Our study was a pilot study, and included only symptomatic women to increase the feasibility of the study (especially in view of the cost of HPV testing) with its objective of evaluating risk factors by maximizing the number of CIN2+ to facilitate the evaluation of an association of CT infection with risk factors, including HPV infection, in such cases. The results may not be synonymous with the risks for asymptomatic CIN2+, the prevalence of which, however, is quite low33. A case-control study design would be ideal to study the association between HPV and CT infection in the general population. Also we did not take into consideration the presence of other sexually transmitted infections, and the sexual behaviour history of the study population. HPV testing is not recommended in women younger than 30 yr, but the exclusion of women younger than 25 yr may have reduced the prevalence of CT infection in our sample.

In conclusion, our study showed no association between C. trachomatis, HPV infection and CIN in this hospital-based symptomatic population. Longitudinal studies starting at an earlier age will be required to determine whether Chlamydia infection acquired in younger age groups has the potential to promote persistence of HPV infection and progression to CIN2+ and invasive cervical cancer.

Acknowledgment

Authors acknowledge the Indian Council of Medical Research (Grant No. S/13/08/04-NCD III), New Delhi, for providing financial support.

References

- GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10. 2010. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomavirus and risk factors for cervical cancer in Chennai, India: A case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:127-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic risks to humans. In: IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Vol 64. Lyon, France: IARC; 1995. p. :409.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of cervical cancer associated with Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies by histology, HPV type and HPV cofactors. Int J Cancer. 2006;120:650-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlamydia trachomatis and invasive cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of the IARC multicentric case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:431-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomaviruses and genital co-infections in gynaecological outpatients. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlamydia trachomatis and human papillomavirus infection in Indian women with sexually transmitted diseases and cervical precancerous and cancerous lesions. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:88-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis DNA in cervical samples with regard to infection with human papillomavirus. J Infect. 1999;38:12-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlamydia trachomatis, herpes simplex virus 2, and human T-cell lymphotrophic virus type 1 are not associated with grade of cervical neoplasia in Jamaican colposcopy patients. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:575-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and HPV infections in cervical samples with normal and abnormal cytopathological findings. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:198-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytologic evidence of the association of different infective lesions with dysplastic changes in the uterine cervix. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1992;13:398-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical presentation of gynecologic infections among Indian women. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:215-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological behavior and etiology of inflammatory cervical smears. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20:199-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kuppuswamy's socioeconomic status scale - updating for 2007. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:1131-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Genital warts and cervical cancer. VII. An improved colposcopic index for differentiating benign papillomaviral infections from high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:611-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Human papillomavirus type distribution in cervical cancer in Delhi, India. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:398-402.

- [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis of human papillomavirus type-distribution in women from South Asia: implications for vaccination. Vaccine. 2008;6:2811-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Co-expression of HSV2 and Chlamydia trachomatis in HPV-positive cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions is associated with aberrations in key intracellular pathways. Intervirology. 2008;51:230-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of Chlamydia trachomatis with persistence of high-risk types of human papillomavirus in a cohort of female adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:668-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlamydia trachomatis infection and persistence of human papillomavirus. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:110-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of Digene Hybrid Capture 2 and conventional culture for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in cervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:641-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Hybrid Capture II CT-ID test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in endocervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1579-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in swab specimens by Hybrid Capture II and PACE 2 nucleic acid probe test. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:303-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The burden and determinants of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in a population-based sample of female sex workers in Goa, India. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:50-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of genital Chlamydia infection in females attending an Obstetrics and Gynecology out patient department in Orissa. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:614-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of human papillomavirus and Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women attending cervical cancer screening in the Republic of Korea. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18:56-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predominance of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars associated with urogenital infections in females in New Delhi, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2700-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis and herpes simplex virus 2 in cervical carcinoma associated with human papillomavirus detected in paraffinsectioned samples. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30:65-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in cervical smear samples with determined HPV. Med Arh. 2004;58:143-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of cervical screening in rural North India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:145-9.

- [Google Scholar]